GOING BEHIND THE SCENES WITH REGIS PROGRAIS AS HE TAKES THE FINAL STEP IN HIS THREE-YEAR JOURNEY TO A WORLD TITLE SHOT

Regis Prograis walked down an echoing corridor at the back of The War Grounds on that early Saturday evening, November 26, 2022. Bright television lights threw eerie shadows across the slate floor and the blue walls as Prograis moved ahead of everyone else. He was quiet and calm as he neared the locker room where he would spend the next two-and-a-half hours preparing to fight Jose Zepeda for the vacant WBC junior welterweight title in Carson, California.

(Photo by Donald McRae)

Prograis had been waiting three years to be back in this position and he could put up with another few hours. Steel lockers lined his dressing room where, at the far end, a giant poster featured a face-off between him and Zepeda above the promotional tagline: Battle of the Best. The 33-year-old from New Orleans, who fights out of Houston, would undertake a brutal test that suited the relatively short but riveting history of this outdoor venue.

The multi-arena complex has been known over the years as Home Depot Center, StubHub Center and now Dignity Health Sports Park, but the 8,000-seat tennis stadium that hosts boxing events has seen so many great battles that the “War Grounds” nickname just stuck. Prograis is a boxing historian and he knew that the definitive war at the site had occurred in March 2013 when Tim Bradley beat Ruslan Provodnikov in a savage bout. It was The Ring’s Fight of the Year. The War Grounds has produced three other Fights of the Year for The Ring since 2008.

The talk all week, during Thanksgiving, had been that Prograis vs. Zepeda could be one of the best contests of a disappointing 2022. It was a rare occasion where two of the top three ranked fighters in a division risked everything against each other.

I know Prograis well, and we had done many interviews over the years, but I was struck by his supreme confidence. All week he had radiated certainty that he would prevail. Prograis was also driven by the hurt he had suffered three years previously, in October 2019, when he lost an agonizingly close majority decision to Josh Taylor in their unification contest in London. It was the only loss on his 28-1 record and, while Prograis had been gracious after a brilliant fight ended in defeat, the consequences were severe.

“I don’t want to be announced as a former world champion,” Prograis told me. “I pride myself on being number one in the world. I look in The Ring Magazine and I’m number one. But when people introduce me now, it’s as ‘the former world champion.’ That hurts. I want to be the undisputed world champion at 140 [pounds]. That’s why this fight is so important.”

Prograis (left) would leave London empty-handed after a razor-thin decision went in favor of Josh Taylor. (Photo by Stephen Pond/Getty Images)

For three years, Prograis had been reduced to scrabbling for another title shot. COVID, boxing politics and a reluctance of those at his level to fight him had contributed to a dearth of decent bouts for Prograis. Since losing to Taylor, he had stopped Juan Heraldez, Ivan Redkach and Tyrone McKenna decisively. But none of those opponents were good enough to push him.

Zepeda was different. The Mexican-American was the hometown favorite and he seemed desperate to win a world title. Zepeda had a 35-2 record and, with his first loss being caused by an injury against Terry Flanagan, he had been unlucky when dropping a majority decision to Jose Ramirez in a 2019 world title fight.

Prograis believed Zepeda had actually beaten Ramirez, but he told me that “Jose has a loser’s type of mentality against me. He’s good and he’s going to try his best, but deep down his confidence is low against me. At the press conference, he even said, ‘Whoever wins will be a real champion.’ I would never say ‘whoever.’ I know I’m going to win.”

Bobby Benton, Prograis’ astute trainer, thought differently. “Zepeda’s just a soft-spoken guy. There’s no doubt in my mind Zepeda believes he’s going to win. They both have to win because it’s so hard for fighters to bounce back from losses. We thought Regis beat Taylor, who is a great fighter, but look how we have battled the last three years.”

“At the press conference, [Zepeda] even said, ‘Whoever wins will be a real champion.’ I would never say ‘whoever.’ I know I’m going to win.”

– Regis Prograis

Benton has been around boxing all his life because his father, Bill, had been a well-regarded trainer in Houston. Bobby first attended a world title fight in 1985. “I was 8 and my dad trained Dwight Pratchett, who fought Julio Cesar Chavez for the world title in Vegas. Dwight was the first to go 12 rounds with Chavez and he’s still in the gym today, training Ammo Williams.”

His deep knowledge of boxing made Benton a compelling witness to this strange old business. When he heard my lament about the miserable state of boxing in 2022, Benton shrugged. “Boxing’s pretty much the same it’s always been. My dad is 74 and the reasons why he didn’t want me in this business is just how the game has always been. It’s always chaotic and difficult.”

Benton was understandably biased, but I thought he was close to the truth when he said of Prograis: “He is the most marketable guy in boxing. Regis is intelligent and well-spoken. He does great interviews and he’s a really special fighter. In a perfect world, he beats Zepeda, defends his WBC belt against a really good former world champion in Jose Ramirez, and then fights the winner of Teofimo Lopez against Sandor Martin. That’s a dream scenario for Regis becoming the superstar he deserves to be.

“I would then love him to fight the winner of Tank (Gervonta Davis) or Ryan Garcia – even if Tank won’t dare fight Regis. He’s too small. But there are a bunch of great fights out there for Regis – like Devin Haney. Even [Vasiliy] Lomachenko is possible if he beats Haney. If Regis has the belts, they have to come through him.”

So much was riding on the outcome of the Zepeda fight that, 90 minutes from their ring walk, the tension escalated. The arrival of Nonito Donaire, a former multiple world champion, was a reminder we were in for a big night. Donaire had fought often at The War Grounds, but his friendship with Prograis had been forged when they shared a bill in Lafayette, Louisiana, in April 2019. Donaire had been the chief support when Prograis became the WBC 140-pound titleholder by stopping Kiryl Relikh.

Prograis’ hands are wrapped as Zepeda’s cutman, Stitch Duran, observes. (Photo by Donald McRae)

There was sheer warmth on Prograis’ face as he embraced Donaire. They spoke for a few minutes and then, knowing what awaited Prograis, Donaire made a discreet exit.

Prograis’ hands were wrapped by Benton, with Stitch Duran watching on behalf of Zepeda. There was a familiar camaraderie and Prograis smiled while his cutman, Aaron Navarro, and Duran swapped stories of bloody gashes and magic potions.

Navarro spoke to me in a corner of the locker room. His 22-year-old daughter, Birdie, had been murdered in Houston 18 months earlier. He wore a shirt that carried an image of her face and a slogan: In Loving Memory of Birdie Navarro.

I thought there were moments when the cutman’s face might crumple as he described his daughter. But Narvarro lightened the mood as he told me about the best Indian restaurant he had ever eaten at – Dishoom in London. “I eat there so often that they absolutely love me.”

Evins Tobler, Prograis’ strength-and-conditioning coach, ambled over at that mention of London. The former long jumper, who had competed against Carl Lewis as a young athlete, was an imposing man. He was also the official cheerleader in the Prograis camp, and all week he had relished the chance to holler support for his man and heap scorn on Zepeda’s corner. Just before he ran Prograis through his warmup, Tobler outlined a program he would use to transform Anthony Joshua’s lack of stamina. If Joshua had been with us, I felt pretty sure he would have considered hiring the impressive Tobler on the spot.

Declan Walsh, a young nutritionist from Ireland, was more restrained. But his impact on Prograis had been profound. “My whole team is solid,” Prograis told me, “and with Declan joining us before my last fight [against McKenna in March 2022], I’m perfect. I used to cut weight in a really old-fashioned way, but Declan changed everything. It’s so easy making weight now. I can stay at 140 [pounds] my whole career.”

Ross Williams, Prograis’ closest friend from New Orleans, had been fascinating company all week as we discussed the two books he had written, both of which offer moving insights into racism in America. Williams sensed the gravity of the night. When I asked him how he was feeling, he made me laugh: “Like I’ve got a midnight storm moving through my body.”

Prograis was levels above Tyrone McKenna in March 2022, stopping him in six rounds. (Photo courtesy of Probellum)

At 7:50 p.m., there was just one fight left before Prograis made his ring-walk. He removed the diamond stud from his ear. His white boxing gloves were pulled on as Tobler boomed: “It’s ass-kicking time, champ…”

Raquel Prograis spoke in Portuguese to her family in Rio while her husband made cries and grunts as he hit the pads. “Total domination,” Tobler yelled. “Yes sir, make that motherfucker pay for all the work you put in.”

Raquel slipped away to her ringside seat. At 8:08, Tobler said gently: “It’s almost time.”

Navarro held a big black punch cushion as Prograis pummeled him. “Don’t forget those short shots inside,” Benton reminded him.

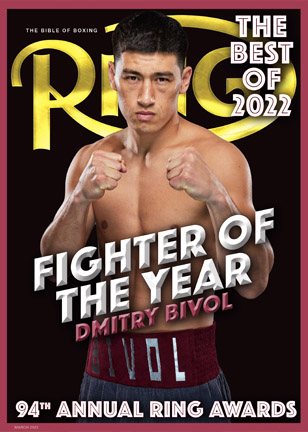

Prograis took a sip of water from a bottle. His eyes stayed fixed on the silent screen where Dmitry Bivol was being interviewed.

At 8:17, the hush was replaced by the arrival of Jermall Charlo, the WBC middleweight titleholder who had been Prograis’ gym mate when they were teenagers. “Take his heart,” Charlo said as he hugged Prograis. “You’re looking good, baby.”

Ducking low under Benton’s swinging left arm, Prograis smacked his blurring fists into the pads. He was hitting hard, with malevolent intent.

The last fight before the main event entered its final round at 8:29. “Break this fucker’s will,” Tobler growled.

At 8:35, a television technician attached a small microphone to Benton’s shirt so that his instructions could be heard on the live broadcast.

A white gown was then draped around Prograis. He would have preferred to walk bare-chested to the ring, like Mike Tyson, but the late November night carried a chill.

As Benton said some last words, another television man walked in. “Let’s go,” he told us before barking into his mouthpiece to a producer, “I’m walking them. … We’re on our way.”

I followed Prograis and his team down that same echoing corridor we had walked two-and-a-half hours earlier. We were through the black curtain and out in the arena a minute later.

Prograis was booed by the Zepeda crowd, but he walked faster and faster. I paused, briefly blinded by the thick and acrid clouds of smoke, as I wondered how Prograis must be feeling as he headed to the heart of The War Grounds.

Zepeda followed soon after, with the Mexican national anthem and “The Star-Spangled Banner” both being received rapturously. Prograis’ Vaseline-smeared face glistened beneath the hot lights.

The bell sounded for Round 1. Zepeda wore black trunks, and Prograis white, as they circled each other. It took 80 seconds for the first meaningful punch to land, and Zepeda’s crisp right hand made the crowd roar. Prograis took it well and marched forward, snaking with concentration, as Zepeda stepped back. They exchanged flurries of blows as the round ended.

Prograis nails Zepeda with a southpaw jab. (Photo by Tom Hogan/Hoganphotos)

Boxing as a southpaw, like Zepeda, Prograis settled behind his authoritative jab and landed a couple of hard lefts. Zepeda came back, but Prograis ducked under most, if not all, of the swinging punches. The crowd chanted “Ze-pe-da, Ze-pe-da!” and “Me-xi-co, Me-xi-co!” While the round belonged to Prograis, the left side of his face looked puffy as Navarro went to work in the corner.

Prograis came out fast for the third, backing up Zepeda and hurting him with a right cross. His jab snapped back Zepeda’s head as they returned to the center of the ring.

Zepeda was cut in Round 4 and he became more passive in the midst of sustained pressure from Prograis, who switched between the head and body. It was an absorbing fight with Prograis in charge of the narrative. But his face showed the marks of battle.

A better round for Zepeda in the fifth encouraged his supporters, but Prograis was undeterred as the action swung back and forth. He knew he would have to work to seal the victory he craved.

By Round 9, Zepeda was struggling as Prograis tagged him repeatedly with his right jab and sweeping left. Sweat flew across the ring with each jolting punch.

Then, in the 10th, after he was buzzed by Zepeda, Prograis let his hands fly. Zepeda stood his ground and both men fought valiantly. A right cross made Zepeda hold on. It had been a fierce round, but Prograis had seen enough. It was time to close the show.

In Round 11, a sharp right and scything left shook Zepeda as he staggered backward. One heavy punch followed another as Zepeda wilted. He began to tumble to the canvas, with the sagging ropes unable to support him, just as the referee jumped in. It had been a brutal end to a punishing fight.

Prograis finally chopped Zepeda down in Round 11. (Photo by Tom Hogan/Hoganphotos)

Zepeda looked dazed as Prograis whirled away – his face lit by exultation. Three years of frustration and hurt gave way to joy. He was back, a world champion again.

The locker room, after the fight, was full of bedlam. “Texas is takin’ over!” Charlo yelled as he hugged Prograis. “I’m so proud of you, dawg!”

I caught their embrace on my phone and, when Prograis retweeted the photograph, he simply wrote: Brothas.

Prograis is embraced by Jermell Charlo after the victory. (Photo by Donald McRae)

There was blood on Prograis’ sweat-stained trunks and he needed stitches to close a cut on the right side of his face, so the boxer and the doctor moved away from the crowd. “I worked so hard,” he said. “Three years I’ve been working for this moment.”

Charlo was still shouting as he and an official argued about whether he and the 20-odd people who had followed him were allowed in the locker room. Prograis gave a gentle smile as if to say: “Boxing!” As he was stitched up, he looked serene.

Speculation as to who he might fight next rose up 20 minutes later when Prograis met the media. After he praised Zepeda, Progais said: “Jose Ramirez been ducking me for five years. Now I got this belt, he wanna fight me? That’s cool. We’ll fight. Then maybe we’ll do a unification fight with Alberto Puello for his WBA title. But everybody knows if I had a hit list, Josh Taylor would be the first on it. I want my get-back more than anything, and I can guarantee I’ll beat Taylor. I’m constantly improving. I wanna be like Bernard Hopkins.”

Speculation as to who he might fight next rose up 20 minutes later when Prograis met the media. After he praised Zepeda, Progais said: “Jose Ramirez been ducking me for five years. Now I got this belt, he wanna fight me? That’s cool. We’ll fight. Then maybe we’ll do a unification fight with Alberto Puello for his WBA title. But everybody knows if I had a hit list, Josh Taylor would be the first on it. I want my get-back more than anything, and I can guarantee I’ll beat Taylor. I’m constantly improving. I wanna be like Bernard Hopkins.”

Prograis’ period of celebration soon ended. The following Wednesday, he tweeted: “I deposited my fight check Monday while I was in L.A. Today the bank emailed me saying the check bounced because of insufficient funds. Somebody better find out what’s going on before I click the fuck out.”

Benton messaged me from Houston. The trainer sounded typically calm. He was sure Prograis would receive his $1,080,000 purse and, in accordance with WBC rules relating to fights for vacant championships, a $240,000 bonus. That bonus represented 10 percent of the $2.4 million purse bid made by MarvNation, the small promotional company based in Southern California.

Prograis relaxes with his family, world title draped over his shoulder. (Photo by Donald McRae)

Prograis was back on Twitter the following day: “I just wanna clarify, I’m good. I got all of my bread right now. I wanna thank MarvNation and Legendz TV. Shout out to y’all. We squared away now. We all good. Thank y’all.”

The boxing circus rolled on. Teofimo Lopez had moved up to Prograis’ division to face Sandor Martin in a WBC final eliminator. Prograis warned Lopez he would hurt him if they fought. Lopez hit back to say Prograis was insisting on a huge purse for a possible fight. “I’m a little disappointed he said it depends on the price. Don’t say you’re gonna knock me out but only if the money’s right.”

On December 10, in New York, Lopez was knocked down and lucky to win a split decision over Martin. Afterward, he looked lost and confused. Alongside his overbearing father and trainer, Teofimo Sr., Lopez said softly: “Do I still got it?”

Bob Arum, Lopez’s 91-year-old promoter, spoke bluntly when asked about a potential fight against Prograis: “You’d have to favor Prograis.”

Prograis was thoughtful and even compassionate toward Lopez. “I think he needs to get rid of his daddy. His dad is living through him and that’s never good.”

Just before Christmas, Ramirez announced that he was no longer willing to fight Prograis for the WBC title. In a lengthy statement, he said he would not accept the WBC’s purse split of 65-35 in favor of Prograis, who offered a six-word tweet in response: “I’ll keep my comments to myself.”

As a boxing historian, and a new world champion, Prograis understood that talk was cheap. All that mattered belonged in the ring, in an arena like The War Grounds, where he had proved again he was a great fighter. Prograis knew there would be many more big fights like that unforgettable Saturday night in Carson. The rest could wait until the next time.