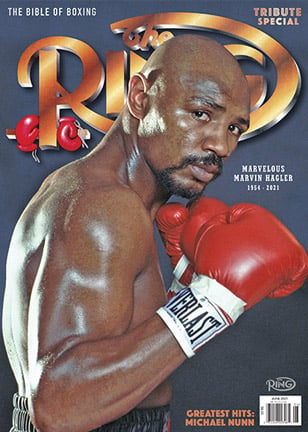

HAGLER’S FRUSTRATION HAD REACHED A BOILING POINT AS HE FINISHED THE 1970s WITHOUT A TITLE, BUT THE ’80s WOULD FINALLY BE HIS TIME TO SHINE

It was less than three months after he’d had his pockets picked and his dreams stolen from him in Las Vegas that Marvin Hagler began his final trek toward becoming what he’d always known he was – marvelous. One could not have faulted him if at that moment he had his doubts.

After 49 professional fights in which more were contested in the gymnasium at Brockton High School than were staged in boxing’s major venues, Hagler had finally gotten his long overdue shot at the middleweight title. It had come only after the Speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill, threatened the sport with a congressional investigation if Hagler was not given his just due, but the justice only lasted until they rang the bell at the Sports Pavilion at Caesars Palace.

READ Leonard-Benitez and Antuofermo-Hagler 1: A Memorable Night at Caesars, by Lee Groves

Less than an hour later, Vito Antuofermo, a man with six cuts on his face that would take 25 stitches to close, was awarded a draw so unsightly that 10 Italian journalists at ringside not known for impartiality when it came to one of their own even agreed Hagler was a clear winner.

“If the judges knew anything about boxing, they would have felt the same way,” Hagler said after Antuofermo retained the Ring, WBC and WBA titles. Once again, the inequities of a cruel sport had been rubbed in his face.

Hagler in London to challenge Alan Minter. (Photo by Monte Fresco /Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix/Getty Images)

Three months later, Hagler stood under dim lights at the Cumberland County Civic Arena in Portland, Maine. Portland is no Vegas, yet there he was, back at the bottom, but not staying there long after bombing out a sacrificial lamb named Loucif Hamani in two rounds.

In another three months, he would return to Maine to flatten Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts in two rounds. Watts had been given a hometown majority decision over Hagler in Philadelphia four years earlier, and this night he suffered for it. Hagler was coming back and didn’t want to waste time doing it.

One more win and he again found himself fighting for the middleweight title, but not against Antuofermo as he had hoped. Antuofermo had been twice beaten by England’s Alan Minter, and now Minter was forced to face Hagler at Wembley Arena in London on September 27, 1980. If Minter had left it at that, things might have gone easier on him, but champions can be a cocky lot.

“I am not letting any Black man take the title from me,” Minter said a few weeks before the fight, tinging the event with naked racism that would spill over on fight night.

Minter later amended his comments, claiming he’d said “that Black man,” as if that somehow made things tidier. Regardless, the crowd at Wembley was a surly lot, led by members of the racist National Front, who hurled bigoted invectives at Hagler on his way into the ring. That didn’t help Minter, who was cut to ribbons from the opening bell until the fight was stopped at 1:45 of the third round with the now-dethroned champion barely recognizable behind a mask of blood. Minter had four terrible cuts, two around each eye, and would need nearly 20 stitches to close them, which explained why he had no quarrel with the stoppage.

When Hagler realized he’d finally won the title he’d chased for seven years and 53 fights, he fell to his knees in the center of the ring. As he did, someone threw a half-filled beer bottle at him, beginning a fusillade of missiles that rained down upon Hagler. Hagler’s loyal lieges, the Petronelli brothers, who had trained and managed him since he was a teenager, formed a human shield around him, placed a bucket over his head and fled the ring. They hurried toward a tunnel under a balcony and then to the police security headquarters rather than their locker room.

Asked what he thought of Minter’s decision to attack Hagler wildly at the onset of the fight, trainer Goody Petronelli snorted, “Coming after Marvin? A damn fool.”

When Hagler returned home to Brockton, Massachusetts, he came without the things he had so long pursued, because who gets to savor victory when you’re being pelted with beer bottles? Once again he had been denied the full glory he’d earned. He’d won the undisputed championship, but no one handed him the belts.

Four months later, he would make the first of his 12 successful title defenses back home at the Boston Garden against Fulgencio Obelmejias. The Venezuelan was 30-0 with 27 knockouts and the universally recognized No. 1 contender, but his resume couldn’t save him from a vicious, one-sided beating. Hagler dropped him in the sixth round with a brutal right to the body and following left uppercut, and then staggered him near the end of Round 7.

When Obelmejias came out for the eighth, he looked like a man heading to the gallows. Referee Octavio Meyran agreed, stopping the fight 20 seconds later after Hagler again rattled Obelmejias’ head.

“I didn’t know what was keeping him up,” Hagler said. Poor judgment seemed a likely cause.

Hagler was back at Boston Garden again in June after having offered Antuofermo a rematch that proved unwise for the Italian to accept. Like their first encounter, the rematch was a bloody one, with Antuofermo doing all the bleeding. Hagler inadvertently sliced him open 30 seconds into the fight when they clashed heads, and Antuofermo’s wise cornerman, Freddie Brown, bought himself three minutes of time to work on the cut by launching into a lengthy argument with the referee claiming the fight should be stopped and called a technical draw. His appeal was denied, and when the second round finally started, Hagler came out and let loose with a five-punch combination, all of which struck Antuofermo in the face. It was clear where this was headed.

By the end of Round 4, Antuofermo was half-blind and his manager, Tony Carione, told referee Davey Pearl he’d had enough even if his fighter had not. Hagler’s reaction to accusations that he’d inflicted as much damage with his head as his hands was without mercy.

“I don’t care how I did it,” he said. “That’s the game of boxing.” Some game.

In his next defense, Hagler cut up Mustafa Hamsho so badly before the fight was stopped at 2:09 of the 11th round that when it was over, the champion mused, “I don’t know what his corner was waiting for. The meat from his eye was hanging down. But I can’t let that bother me. I have to think, ‘Better him than me.’”

Hamsho needed 55 stitches to close the gashes around his eyes. He had failed to win a single round. So dominant was Hagler that one of the judges scored four of the rounds 10-8 … without a knockdown.

ABC did Hagler’s next opponent, Caveman Lee, no favors when it refused to introduce Hagler as “Marvelous.” According to Hagler’s attorney, Steven Wainwright, when he and the Petronellis protested, an ABC executive told them, “If he wants to be called Marvelous Marvin at ABC, tell him to go to court and have his name changed.”

Irked by this latest slight, Hagler took it out on Lee, bombing him out in 67 seconds. He then went to court and had his name legally changed to Marvelous Marvin Hagler. He had been marvelous long before that, but now it was official.

With the big money Leonard was making still eluding him, Hagler was forced to agree to fight at 3:30 a.m. in San Remo, Italy, seven months later in a rematch with Obelmejias. Hagler had long said his motto was “Destruction (sometimes simply ‘Destruct’) and Destroy,” and to accommodate the 2,000 Italians in attendance at Teatro Ariston, he sported a T-shirt that read: “Distruzione E Distruttore.” They got the message. Soon, so did Obelmejias.

Having learned his lesson in their first fight, Obelmejias took a lot less punishment before being knocked out at 2:35 of the fifth round in another one-sided affair. In the crowd was Leonard, who had invited Hagler to come to Baltimore the following week for a press conference, where it was expected Leonard would announce a comeback to face Hagler after healing from a detached retina.

Leonard told Hagler several times that week in Italy how big the fight would be, which led Hagler to say to Leonard on American television after he’d destroyed Obelmejias, “If we’re such good friends, give me a payday.” Later, Hagler told friends, “I put him on the spot.” Turns out he didn’t.

Hagler made the trek to Baltimore dressed in a tuxedo, only to hear Leonard say “it’ll never happen.” He wasn’t about to challenge perhaps the best middleweight who ever lived, leaving Hagler angrily pursuing one-sided wins over guys like Tony Sibson (TKO 6) and Wilford Scypion (KO 4).

Poor Sibson had an apt description of what it was like to face Hagler when he said after having been knocked down twice, “I couldn’t find him for the first two rounds. I asked myself, ‘Where did he go?’ But I knew he was there, because he kept hitting me.”

By the end, Sibson had gashes over both eyes and his nose and mouth were bleeding. After looking at his disfigured face in a mirror the next morning, he told a reporter, “I never believed anyone could do to me what he did. That Hagler’s an artist.”

The kind of damage Hagler regularly inflicted over the years once led his manager, Pat Petronelli, to say, “He’s retired more fighters than old age. Marvin gives the hospital a lot of business.”

Six months after stopping Scypion, Hagler finally got his first opportunity to fight a legend when he faced Roberto Duran, who was 77-4 and had made a surprising comeback. After having looked like a shadow of himself in back-to-back losses a year earlier, Duran rallied to beat former welterweight champ Pipino Cuevas and then WBA junior middleweight titleholder Davey Moore five months before agreeing to face Hagler. The Hands of Stone were back.

The pace was uncharacteristically cautious that night until Hagler rocked Duran in the sixth round but failed to press that advantage. Soon after, Duran climbed back into the fight. He thumbed Hagler in the left eye in the next round, causing significant swelling. A clash of heads had Hagler’s eye bleeding in the 13th. When the round ended, Duran led on two scorecards and was even on the third.

It appeared Hagler’s reign was about to end, but he marshaled the fury of all those past slights, real and imagined, and won the last two rounds by constantly pressuring a tiring Duran. Hagler’s close but unanimous decision led critics to insist he’d been intimidated, missing entirely what he had accomplished.

“It seemed everyone was disappointed that I didn’t knock him out,” Hagler said. “I felt that way myself, but he wasn’t that vulnerable to a knockout. You don’t barrel in there on a guy like Roberto Duran. I’d been effective and was winning the fight, so it isn’t like I had to go in there and take the punishment to bomb him out.”

“It seemed everyone was disappointed that I didn’t knock him out,” Hagler said. “I felt that way myself, but he wasn’t that vulnerable to a knockout. You don’t barrel in there on a guy like Roberto Duran. I’d been effective and was winning the fight, so it isn’t like I had to go in there and take the punishment to bomb him out.”

For someone whose mantra had always been “Destruction and Destroy,” it seemed an odd response. But soon after, he returned to his more familiar ways at the expense of challengers Juan Roldan and Hamsho in a rematch, two wins that set the stage for his signature moment – a fearsome confrontation with Thomas Hearns on April 15, 1985.

READ Best I Faced: Marvelous Marvin Hagler

Roldan took a one-sided beating for 10 rounds but did get credit for the only knockdown of Hagler’s career. Frankly it is difficult to knock someone down when the punch you throw misses its mark, but Roldan pushed down on Hagler’s neck on his follow-through and the champion’s back foot slipped, and down he went.

Hagler argued the point with the referee but didn’t win, so he took it out on Roldan. By the third round, Roldan’s right eye was nearly shut and he was basically a cyclops thereafter. Considering how poorly he’d done with two eyes, this was a distinct disadvantage.

Unbelievably, Hagler’s rematch with Hamsho was the only time the champion fought in Madison Square Garden, but he didn’t stay long, stopping Hamsho at 2:31 of the third round. Hagler had entered this fight particularly surly after Hamsho twice insulted him, leading the champion to remark, “Hamsho was better off when he didn’t speak English. I don’t want to see this man’s face any more. Eliminate!”

So he did. When Hagler dropped Hamsho, it was the first time the challenger had been off his feet in 43 fights. Hamsho had needed 55 stitches after their first meeting. This time all he needed was a pillow. As things would turn out, so would Hearns.

Hagler’s epic clash with Hearns was the first megafight of his career, and it began with a two-week, 22-city promotional tour that led to Hagler hating everything about the boastful Hearns. Hearns was 40-1 with 34 knockouts, his only loss being to Leonard. Brimming with confidence, he kept promising the fight would be over with Hagler knocked out in three rounds. He was half-right.

The opening round is widely considered the most ferocious three minutes in boxing history. Each man sandblasted the other, but the key moment came when Hearns twice exploded massive right hands on Hagler’s head. Hagler wobbled for an instant but refused to buckle. Hearns’ hand did instead, breaking in several places. Hearns had planned to box the first half of the fight, but Hagler’s relentless pressure now forced him into a firefight he could not win.

A severe cut had opened up in the middle of Hagler’s forehead in the opening round and referee Richard Steele twice called for the doctor to examine it. The second time came in Round 3 and Hagler was convinced the powers that had so often conspired against him were about to steal his title. Enraged when Steele asked if he could see, Hagler snapped, “I ain’t missing him, am I?”

A bloodied Hagler blasts Hearns with a right.

Fearing judges’ pencils more than Hearns’ fists, Hagler attacked again, hurting Hearns badly with a chopping right and then two hard shots on the hips. Rubbery legged, Hearns reeled backward, seeking an escape route where none existed. Hagler chased him down, pinning him on the ropes and finishing him with a crushing right to the jaw. Hearns went limp and collapsed on his back, his eyes unseeing.

Somehow Hearns rose at the count of nine but was defenseless. Before Hagler could finish him, Steele wrapped Hearns in protective custody. Eight seconds shy of eight minutes, the fight was over. Tommy Hearns had been right about the round but wrong about whose greatness would be confirmed in it.

After 65 professional fights and 61 victories, Marvelous Marvin Hagler was finally the superstar he’d long believed he was. He was favorably compared with Carlos Monzon, whose record of 14 consecutive title defenses he was closing in on. He became a pitchman for various products and a regular guest on television talk shows. All that was left was pursuing Monzon’s record.

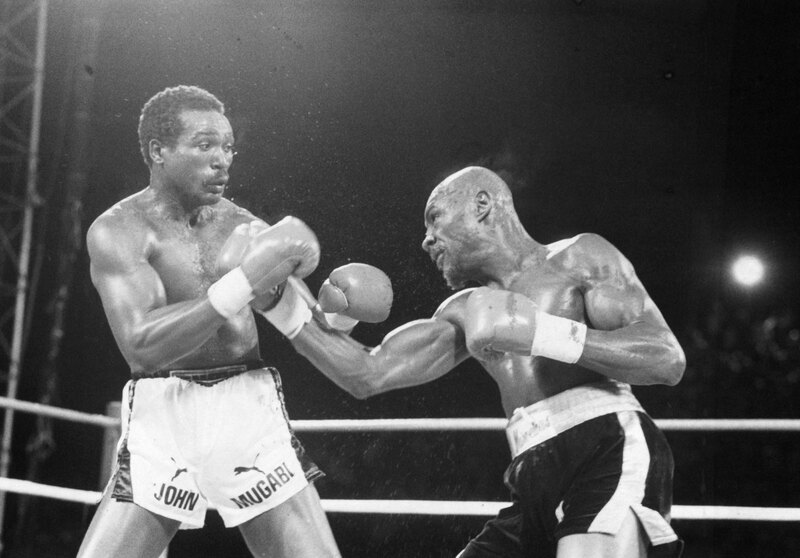

Just under a year later, he would make his 12th title defense against a man so fearsome he was called “The Beast.” Who but Hagler would face Hearns and John Mugabi, 25-0 with 25 knockouts, in back-to-back fights?

Hagler vs. John Mugabi (Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images)

The two had fierce exchanges through the first half of the fight, with Mugabi giving as good as he got, but by the end of the 10th the challenger sat spent and badly beaten in his corner as his manager, Mickey Duff, exhorted him to press on. “Do it for the children, John! Do it for the children,” Duff pleaded.

As much as he loved his children, Mugabi was a beast no more. He was just another guy who couldn’t stand up to the punishment Hagler relentlessly dished out. When Hagler dropped Mugabi with a barrage of punches barely a minute into Round 11, “The Beast” sat crumbled where he landed, his arms resting on his knees, as the referee counted him out. It was the 11th time Hagler knocked out a challenger in his epic run of defenses.

After the fight was over, Hagler’s years of being marginalized and ignored spilled over and he barked, “I took a guy with all those knockouts and I destroyed him. Him and Hearns, back to back. Now maybe all those doubters will shut up.

“They been trying to get rid of me for years. I believe they really won’t give me credit until I’m done with the game. It’s like I haven’t proven myself yet. What do they want? The record, that’s what I’m looking for.”

Marvin Hagler would not fight again for 13 months. When he did, he would get his long-held wish. Sugar Ray Leonard had surprisingly agreed to come out of a three-year retirement to face him in Las Vegas, the city of long odds. It was the only time Leonard earned less money than his opponent, in part because he paid several million dollars to convince Hagler to accept a 12-round fight instead of the normal 15, a larger-than-normal ring and 10-ounce gloves instead of eight. Except for the fact they ended up earning Hagler $20 million to Leonard’s $12 million, those decisions proved to be unwise.

The IBF refused to sanction the fight and the WBA stripped Hagler for not facing its No. 1 contender, leaving only the WBC belt at stake, but the truth was this fight was never about belts to Hagler. It was about evening all the scores he felt had gone against him for so many years during his climb from nowhere to Marvelous. In his opinion, Leonard had always had a silver spoon in his mouth while he’d had no spoon at all. It was payback time.

Hagler was the aggressor all night, but Leonard was elusive, fighting only in spurts in the first few seconds and final 30 seconds of each round. He was a master illusionist in a town that loves magicians, and he mesmerized two of the judges, escaping with a controversial split decision that left Hagler stunned and convinced he’d again been victimized by the politics of boxing.

Leonard made Hagler look awkward at times but spent most of the fight in retreat, leading Hagler to holler at one point, “Fight like a man, you little bitch!” Instead, Leonard fought like a disappearing act, winning a split decision still argued over 34 years later. One of the most apt analyses of what happened was penned by the great British boxing writer Hugh McIlvanney for Sports Illustrated. He called the decision “an epic illusion.”

For a year, Hagler pursued a rematch, but Leonard had retired again. Finally, so did Hagler, moving to Milan, Italy, to pursue an acting career. He starred in several action films, remarried and built a happy life for himself. Three years after their first fight, Leonard had promoter Bob Arum approach Hagler about a $15 million rematch. Hagler replied with the ferocity he’d so often shown in the ring.

“Tell Ray to get a life,” he said.

When Hagler was later asked about that moment, he smiled serenely and said, “I considered the $15 million, but it didn’t come close to changing my mind. If I didn’t understand what happened in that fight, then it would bother me. But I understand. They took the fight from me. Boxing screwed me one last time.”

READ Sugar Ray Leonard: “If my win could be reversed to bring him back now, I would give it away.”

He may not have broken Monzon’s record, but he beat the boxing game. Marvelous Marvin Hagler retired with a 62-3-2 record and 52 knockouts. He is on the short list of the greatest middleweights of all time. More significantly, he was one of the few who never answered the siren call of a comeback. The same unbreakable will he’d shown throughout his career that allowed him to destroy Tommy Hearns and so many others gave him the steel never to return.

His last act inside a boxing ring had been a disdainful wave in the direction of the judges after the Leonard decision was announced. Then he just walked away.

Hagler saved much of the estimated $40 million he earned in boxing and lived a contented life until passing away unexpectedly at the age of 66 on March 13 at his summer home in New Hampshire, where he and his wife had gone to escape the COVID-19 virus sweeping across Italy. The exact cause of his death was not announced, but for anyone who saw him fight, you knew it wasn’t from a heart problem.