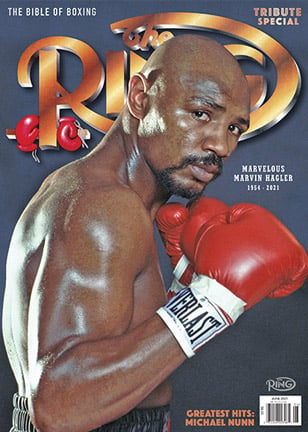

PUTTING AN OCEAN BETWEEN HIMSELF AND BOXING, HAGLER GAVE UP THE RING TO PURSUE AN ACTING CAREER IN ITALY, BUT HIS RENUNCIATION ONLY ADDED TO HIS ENDURING MYSTIQUE

The announcement felt anticlimactic. It was Sunday, June 12, 1988. Marvelous Marvin Hagler had been ringside for NBC, providing commentary, while his brother Robbie Sims lost a 12-round decision to Sumbu Kalambay in Ravenna, Italy. After the verdict was given, Hagler was asked about his own future. He’d been away from boxing, and people were wondering if he would ever fight again. He casually told the television audience that he was “going to say goodbye to boxing, retire and go into the movies.” »

He later said this was “the saddest day” of his life. At the time, it happened with the proverbial whimper, rather than a bang. It was hard to believe that Hagler, at 34, was done with boxing.

Disillusioned by his 1987 loss to Leonard, Hagler never fought again. (Photo by Jim Wilson/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Just weeks earlier, he’d walked into the Brockton gym office of his longtime trainer and mentor, Goody Petronelli. Hagler declared right then that he was going to quit boxing. He’d had enough of it.

“I was a little surprised,” Petronelli said many years later. “I asked him, ‘Is that really what you want to do?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ I think he was tired of the training, because no one ever trained like Marvin Hagler. I think he was tired of that, more than the fighting.”

Petronelli gave Hagler a hug and simply congratulated him on what had been one hell of a career. Hagler didn’t want the newspapers to know about his retirement, so Petronelli promised to stay quiet on the subject. Of course, there were many more discussions about it, because Petronelli felt his fighter would come back if the money was right. “One time,” Goody recalled, “Marvin, my brother Pat and myself stayed up until three in the morning, sitting in Pat’s kitchen. We’d say, ‘Marvin, are you sure?’ And he’d always say, ‘Yes. I’m sure.’ He wanted to go and enjoy life. People would ask us, ‘Is Marvin fighting again?’ We’d just say he was in Italy. That’s where he was most of the time.”

During the next two years, Hagler’s name sporadically appeared in boxing columns, usually in reference to comeback rumors. Some of the talk included Hagler taking part in a tournament to name a new middleweight champion, where he might fight Michael Nunn or James Toney, while Ray Leonard even approached Hagler with an offer for a return bout. Hagler wasn’t interested. There were occasional meetings between the Petronellis and Bob Arum, but all of the talk and speculation amounted to nothing. By 1990, Hagler was officially divorced from his first wife, Bertha, and living in Milan.

The myth, of course, is that Hagler went overseas and became a movie star. That’s a slight overstatement, the work of gullible sportswriters trying to attach a happy ending to Hagler’s often bitter life story, but it is true that he appeared in four movies. At one point, he was taking acting classes and having meetings with Hollywood types. He’d allegedly been offered roles where he’d play a boxer, which he turned down. He also didn’t want to play characters where drugs were involved, since that would be setting a bad example. This was ironic, because Hagler was no angel when it came to partying.

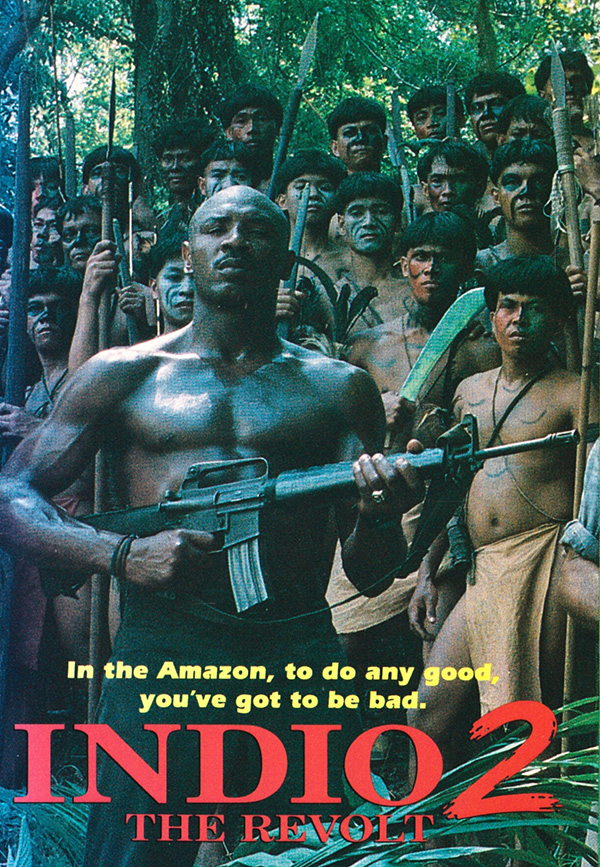

By the time Hagler bolted for Italy, he had appeared in the NBC sitcoms Punky Brewster and 227. He’d also appeared in a popular Pizza Hut campaign and then joined Hulk Hogan and football’s Brian Bosworth in a promotion for Right Guard deodorant sticks. Pleased with his cut-rate TV stardom, Hagler vowed to “get the taste of boxing out of my mouth.” He still consented to interviews in that 1989-90 period, insisting that he had given up boxing to be in movies. Acting, he said, was better than getting whacked in the head for a living. Soon there was talk of Indio, Hagler’s first starring role. Boston sportswriters joked that Hagler was in a jungle somewhere, trying to become the new Rambo.

Indio was a cheap Italian action flick in the vein of American movies such as First Blood and Missing in Action. Filmed in locations ranging from South America to the Philippines to Borneo, the movie ended up in the dreaded “direct to video” category, the place where mediocre films were relegated in those days. Indio was neither terrible nor good; it was just a quickie project to cash in on a popular genre. Hagler seemed happy, though. That was all that mattered. He sent pictures back to the Petronellis, funny shots of himself in a jeep, riding through the muck of a makeshift movie set.

Another myth is that Hagler made a smooth transition into retirement. The truth is that he went through a long rough patch. His marriage fell apart. He drank too much. There was some shameful behavior, including a charge of beating a woman in a Boston hotel, to which he pleaded guilty and served a year’s probation. At one point, the mayor of Brockton removed a picture of Hagler from City Hall. The mayor felt it was wrong to celebrate such a man. The picture was put back a few years later, but there was a period where Hagler’s conduct was poor. Between court dates, there was his 1993 induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and, of course, plenty of talk about his so-called movie career.

Few took note of Indio, though its director, Antonio Margheriti, promptly put Hagler in Indio II: The Revolt (1991). Margheriti, a veteran of low-budget Italian cinema, called upon Hagler again in 1997 for Virtual Weapon, a detective drama with a screenplay by the Fight Doctor himself, Ferdie Pacheco. Hagler also costarred in Notti di Paura (1991), an Italian production filmed in Russia. Four movies in eight years was fair for an ex-boxer, but certainly not the pace Hagler had wanted. Sportswriters continued to focus on Hagler the actor because it was an easy angle, but even Hagler sensed his movie career had gone cold. “I’m having the same struggles in the movie industry I had in boxing, but boxing taught me patience,” Hagler said in 1997.

Few took note of Indio, though its director, Antonio Margheriti, promptly put Hagler in Indio II: The Revolt (1991). Margheriti, a veteran of low-budget Italian cinema, called upon Hagler again in 1997 for Virtual Weapon, a detective drama with a screenplay by the Fight Doctor himself, Ferdie Pacheco. Hagler also costarred in Notti di Paura (1991), an Italian production filmed in Russia. Four movies in eight years was fair for an ex-boxer, but certainly not the pace Hagler had wanted. Sportswriters continued to focus on Hagler the actor because it was an easy angle, but even Hagler sensed his movie career had gone cold. “I’m having the same struggles in the movie industry I had in boxing, but boxing taught me patience,” Hagler said in 1997.

In 2004, Sports Illustrated ran a “Where are they now?” story on Hagler. Without mentioning that he hadn’t been in a film for seven years, he claimed he was waiting for that one big role that would change everything. “If the call comes, I’m going to be ready,” Hagler said. In truth, the Italian film industry was done with Marvelous Marvin. His resume stood at four films. He stayed reasonably active as a ringside commentator for bouts in Britain, but there were no more movies.

What Hagler may not have realized was that once he was out of boxing, he lost much of his appeal to producers and directors. The novelty of casting a boxing champion or any active athlete in a film is valid, if only for exploitation of his name. But the longer a boxer is retired and out of the public eye, the less market value he has on a movie poster. Another factor is that Margheriti, the one director who seemed to like Hagler, died in 2002. Had Margheriti lived longer, he might’ve given Hagler another role to play.

The bittersweet part of this is that Hagler seemed to really like the idea of acting. Just before his bout with Thomas Hearns, he signed up with talent agencies in New York and Los Angeles. He also hired an agent, Marty Klein, who handled such stars as Steve Martin and Mary Tyler Moore. One of Hagler’s first offers was a tempting one – the role of Hawk in ABC’s Spenser: For Hire, a pilot episode based on the popular Robert B. Parker novels. Spenser, played by Robert Urich, was a Boston private eye, and Hawk was his street-smart sidekick. Warner Brothers was apparently serious about casting Hagler.

Unfortunately, Warner Brothers wanted actors to sign a long-term contract in case the pilot movie was picked up for a series. Hagler couldn’t oblige because he was about to start training for Hearns. Hagler was excited about acting, though. “I want to show people I can talk, that I am colorful,” Hagler said. “I have other abilities than just fighting.”

He never quite gave up on the dream. Just six months before his death, Hagler told The Boston Herald, “I’m looking for another shot at a movie.”

Hagler with martial arts movie star Chuck Norris in 1987. (Photo by Wendy Maeda/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

The real story of Hagler in retirement, however, has nothing to do with whether or not he was a movie star. The real story, and the one that tells us a bit about Hagler’s inner workings, is about his flight from America.

Moving to Italy was a gamble, but he’d always liked it there. Early in his title reign, he fought in San Remo and was treated like a star. One might say that European boxing fans were quicker to embrace Hagler than Americans. The notion that he was more popular overseas must’ve stayed in his mind. When it looked like the Italian film business wanted him, that was enough incentive to pull up stakes in America and move on.

Relocating to Milan wasn’t simply a way to thumb his nose at boxing or America. It felt that way to some observers, but there were more layers to Hagler’s decision. He wanted to find a place where he wouldn’t be constantly scrutinized, where he could party a bit without finding himself on the Boston nightly news. He craved privacy. One of the first things he did after winning the championship in 1980 was install a giant fence around his house to keep kids out of his yard. Now, as a former champion, he was putting up the biggest fence imaginable, an entire ocean between him and America. Italy became home.

“What happened was I wanted to move. I needed a change in my life.”

“I like the country, the culture, the people,” Hagler told SI’s Rick Telander in 1990. “And I knew Milan had people who could help me get into movies. What happened was I wanted to move. I needed a change in my life. People said I wouldn’t last a week here, and, I’ll tell you, this was a challenge. The first day I was here, I got locked in my room because my landlady didn’t speak English, and I had to jump off the balcony, and then I had nothing to eat and no lira, and I’m this black guy who doesn’t speak Italian, and, you know, I stuck it out because I’m a survivor. Now I love it here.”

He also hired an attorney to run interference between him and all of those people trying to reach him, the people Hagler assumed were trying to make money off of him. Even some of Hagler’s closest friends were denied his phone number. They had to contact him through his lawyer.

Hagler’s big fear was that one bad business deal could cost him the fortune he’d earned by fighting. There’s no telling how much money he frittered away during his reckless years or forked over during his divorce. Now he simply wanted to keep his millions – and keep his sanity.

There were efforts made to lure Hagler back to America to attend Las Vegas events. His friends told him he should be more visible, otherwise the public was going to forget him. He was unconcerned; he had a home in New Hampshire, where he stayed in the summer, and he attended the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s induction weekends almost every year. But as the 1990s turned into the 2000s, he showed less interest in revisiting the boxing world. He was good to fans, he enjoyed certain charity events, and there are dozens of stories where he gladly took time to sign an autograph or pose for a picture, but generally he laid low. We didn’t see him at big fights, and when offers were made for him to appear somewhere, he rejected far more than he accepted.

The former champion enjoyed attending the yearly festivities at the International Boxing Hall of Fame.in Canastota, New York, like this “Parade of Champions” in 2018. (Photo by Alex Menendez/Getty Images)

If Hagler had a concern about being forgotten, he never showed it. He’d had all the accolades a man could want and had made more money than he’d ever imagined. He’d been deemed by Sport magazine the highest-paid athlete in the world for two consecutive years, 1983 and ’84, back when it was shocking for a sports figure to make $5 million in a 12-month span. If he wanted to relax and be away from the crowd, he’d certainly earned the right. He occasionally appeared at major events – a 1997 trip to South Africa where he met Nelson Mandela and helped promote a PPV bout involving Roberto Duran was both lucrative and interesting for him – though he did things at his own pace and on his own schedule. While Duran lived out the clichéd life of an aging pug still trying to make a buck, Hagler was content to live well, eat well and travel well. That became his story. He let the others fight; he was glad to be away from it all.

Hagler squares off with Nelson Mandela. (Photo Louise Gubb/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

But if Hagler’s name meant a bit less to the general populace with each passing decade, he seemed to become more fascinating to boxing fans. The fans who had enjoyed him in the 1980s were joined by a new generation that had learned about him through YouTube clips. These new fans recognized a genuine badass when they saw one. The old fans recalled him with nostalgia. As the 2000s rolled along, it was clear that there weren’t many fighters like Marvelous Marvin. More than one professional football coach, including Bill Belichick, showed the Hagler-Hearns fight to their teams before important games, trying to rev them up. It usually worked, too.

In a way, Hagler’s stature grew without him trying so hard. His so-called isolation served to nourish the aura of mystery that legends require. He didn’t have to appear at every stinking memorabilia convention and hotel opening, smiling when he didn’t feel like it, engaging with strangers. He was content to stay out of the spotlight and let his work speak for him. He was like a rare coin. When he did turn up, it was damned special.

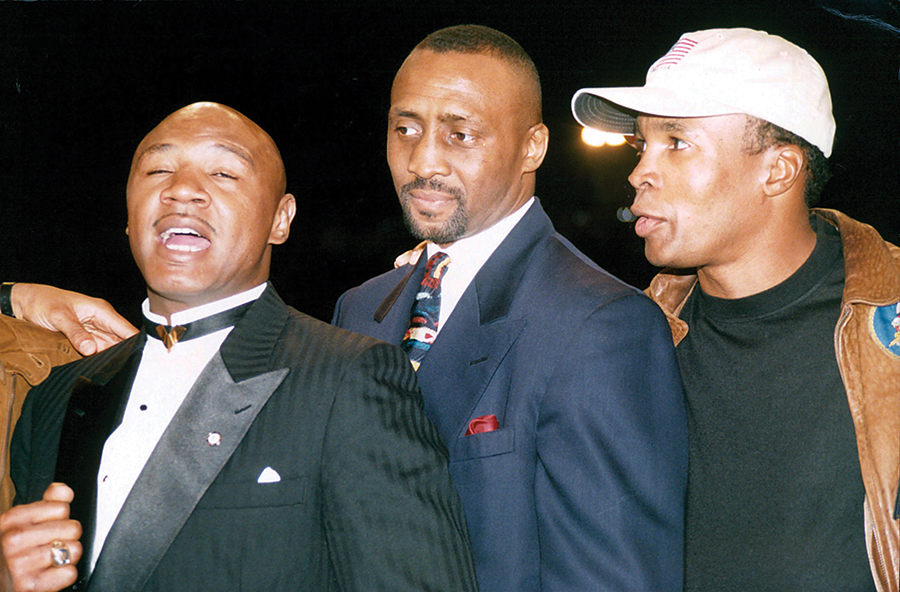

During one of his stateside visits, Hagler was a guest at a star-studded Caesars Palace event. His old rivals Leonard and Hearns were at nearby tables. Eventually, Leonard approached Hagler and proposed the three of them work together and establish a promotional group. As he related the story to the Boston Globe in 1997, Hagler felt that Leonard was simply being greedy, wanting to cut in on the action of younger fighters. Hagler never liked sharing the spotlight with anyone, and he wasn’t about to join forces with Leonard. He told Hearns and Leonard to “get a life,” and he walked away.

With the 2008 publication of The Four Kings by author George Kimball, it became standard to refer to Hagler, Leonard, Hearns and Duran as a sort of four-headed beast that ruled boxing in the 1980s. Though the book’s title remains a popular catchphrase, Hagler disliked the whole notion of “the four kings.” Looking at it from his point of view, we can understand why. He defeated Hearns. He defeated Duran. In his mind, and the minds of many others, he defeated Leonard, too. Why, Hagler wondered, was he being tied in with them forever? When a BBC commentator asked him about it on a panel show, Hagler sneered. “There was only one king,” Hagler said. “And it was me.”

Hagler, Hearns and Leonard in 1995. (Photo by The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

Generally, however, Hagler spent his final years as a magnanimous fellow. He appeared to find great happiness with his second wife, Kay. He loved boxing but kept it at a comfortable distance behind him. He appreciated being remembered, and he understood his place in boxing history, though he possessed a kind of humility when talking about himself. The old anger he carried for so many years seemed to melt away. Life was good.

Interviews became less frequent, and he usually said the same old things. He had his pat answers and didn’t bother trying to be verbose. Now and then, however, he could startle you with an insight. In 2017, he appeared on a YouTube channel called This is Opus, where he was asked to define greatness. Looking aged and slightly battle-scarred, he scratched his famous bald head and laughed. Then he turned serious.

“Greatness is something you can’t really touch,” he said. He talked a bit more on the subject. He talked about never being satisfied during his career, which is what pushed him forward. Speaking this way had never been his strong suit, and it is fascinating to watch him search for the proper words, digging in like a jazz player trying to find the right notes. “I don’t think I’ve achieved greatness yet,” he finally said. “It could still be out there.”

Of Hagler’s many bold incarnations – the angry man, the champion, the recluse – this might’ve been the very best of them. Here was a fighter far away from his most glorious days, still baffled by the secret of greatness, offering nothing but a friendly smile. This was better than being the new Rambo. He was a man at peace.