HAGLER’S ARDUOUS RISE THROUGH THE AMATEUR AND PROFESSIONAL RANKS WAS PRECEDED BY A CHANGE OF SCENERY AND A FORTUITOUS UNION WITH THE PETRONELLI BROTHERS

Serendipity is where chance becomes good fortune.

Some words, of course, have different meanings or interpretations. Was it “serendipitous” that 15-year-old Marvin Nathaniel Hagler and his family relocated from the abject poverty and violence of his old neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey, to the comparative safety of Brockton, Massachusetts? Or that the introverted Black youth who preferred the company of pigeons to most humans found a pair of caring white mentors in brothers Goody and Pat Petronelli, who introduced him to boxing and thus put him on the path to ring immortality.

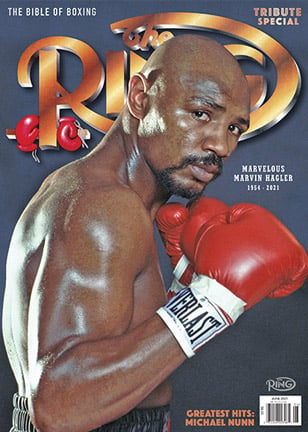

Given the purview of historical context, the short answer to both questions would have to be yes. But to remember Hagler, who was 66 when he died unexpectedly on March 13 of this year in Bartlett, New Hampshire, solely as a shaven-skulled wrecking machine inside the ropes is to deny him his due as a fascinatingly complex individual shaped by myriad influences. Winston Churchill once described Russia as a “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” which is as apt a description as any of the multifaceted Marvelous Marvin Hagler, who had his name legally changed in 1982. When fight night arrived, the same gracious and affable guy who loved coming back to the International Boxing Hall of Fame (into which he was inducted in 1993) to chat up fans, sign autographs and pose for pictures could readily summon a more threatening side of himself. He called it “the Monster coming out,” and it was a voracious beast that struck fear into many opponents as Hagler battered his way to a 62-3-2 professional record with 52 knockout victories.

“I always wanted to be somebody.”

Before one of his 12 successful title defenses, against Fulgencio Obelmejias, Hagler – whose self-applied motto was “Destruct and Destroy” – vowed to do to the Venezuelan what he had already done to a host of other victims, and would continue to do as long as the Monster could be periodically freed to do what it did best. “I’m going to kill him,” predicted Hagler prior to their 1982 rematch, his inner well of meanness again swelling during another training camp that entailed as much mental preparation as physical. “They can’t stop me. I’ll kill them all!” Not surprisingly, Obelmejias, his face badly swollen, went down and was counted out in the fifth round.

An 18-year-old Hagler defeated Terry Dobbs to win the 165-pound National AAU championship. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

The more foreboding side of Hagler was described thusly by journalist Brian Doogan, a former contributor to The Ring, in his book about Hagler’s showdown with Sugar Ray Leonard, The SuperFight: “He was a tremendously skilled, technical boxer and he worked prolifically on those skills in order to perfect his dark art, but he also had an almost barbaric dimension, a place he could go to that was beyond most people’s imaginings.”

Who and what any of us are is a combination of nature and nurture. In young Marvin’s case, the primary nurturer was his mother, Ida Mae Hagler, who did the best she could for her children: In addition to Marvin, her eldest, there were four daughters and another son, Robbie Sims Jr., who eventually became a middleweight contender himself. Marvin’s father, Robert Sims Sr., abandoned the family when the children were young. But Ida Mae’s unwavering devotion counted for only so much when it came time to pay the bills, which obligated her and the kids to remain in the almost exclusively Black Central Ward ghetto in Newark, where the rents were low, the walls thin and the crime rate high.

Mentally sharp but socially awkward, Marvin spent a lot of solitary time on the roof of the rundown tenement building in which the family resided, where the future champ, as later would be the case with Mike Tyson in Brooklyn, kept a pigeon coop. It was mostly there that Marvin dared to imagine himself doing great things in the competitive arena.

“I always wanted to be somebody,” Hagler told Sports Illustrated writer William Nack for a lengthy profile that appeared in the magazine’s October 18, 1982, issue. “Baseball, I played like I was Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays; basketball, I’d be Walt Frazier or Kareem; boxing, I’d pretend I was Floyd Patterson or Emile Griffith.”

From left to right: Tony Lopes, Tommy Rose, Hagler, Ricky Wynn, Danny Tratzinski and Dick Ecklund. (Photo by Boston Globe Archive via Getty Images)

Perhaps, in a different setting that had more green spaces, the athletically inclined Marvin Hagler might have been able to make a run at becoming an ersatz Mays. At his fully grown adult height of 5-foot-9½, becoming a faux replica of Walt Frazier was unlikely, and stepping into the oversized sneakers of the 7-foot-2 Abdul-Jabbar was simply crazy. But if there really is such a thing as serendipity, be it in Newark or Brockton, there was at least a chance Marvin might have found a way to actually live his dream in boxing, the quintessential urban escape route for hungry kids handy with their fists.

“He always said he wanted to be a boxer,” Ida Mae told Nack of her son’s athletic ambition that had shorter odds of reaching fruition than the ones he had envisioned on the diamond or on the court. “I didn’t believe him when he said he wanted to be like Floyd Patterson. I thought he’d become a social worker.”

The family’s worsening finances curtailed any academic goals Marvin might have harbored, and, as a 14-year-old high school freshman, he dropped out to take a minimum-wage job in a toy factory. His quitting school, however, came a year after the five-day race riot that began on July 12, 1967, and got worse when a Black woman was shot and killed by a Newark police officer on July 15. By the time order was finally restored in the smoldering remains of the Central Ward section, 26 people (one cop, one firefighter and 24 residents) were dead, 700-plus injured and almost 1,500 arrested. The cost in property damage, $11 million, might not seem like much now, but that equates to more than $86 million in today’s dollars.

Aware that a bullet need not be directed at a specific target to snuff out a life, Ida Mae directed her brood to prostrate themselves on the floor for almost the entire duration of the conflagration going on three stories below. Despite such precautions, two slugs smashed through a bedroom window and shattered the plaster above the bed of Marvin’s sister Veronica.

In 1969, another Newark riot, albeit one that lasted only two days and did not result in any deaths, convinced Marvin’s mother that remaining in Central Ward put her and her kids at more risk than she was willing to accept. Ida Mae called a relative in Brockton, once renowned for its shoe factories and later as the hometown of heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano, and asked her to help find a more suitable place to which the family could relocate.

“I felt out of place, going from an all-Black society to a mixed society … I had to learn for myself how people really were.”

Brockton proved to be a “relief” and “wonderful,” in Ida Mae’s estimation, primarily because of the reduction in the sound of gunfire and police sirens at night. But for Marvin, who was accustomed to being in a virtually all-Black environment, the transition into an ethnically diverse, blue-collar community of native New Englanders, French Canadians, Lithuanians, Italians and Irish, with a smattering of African Americans and Puerto Ricans, proved somewhat daunting.

“I felt out of place, going from an all-Black society to a mixed society,” he told Nack. “The only place I’d run across whites was in stores. They were always behind the counters, taking the cash. School principals. Police. The post office. I really didn’t trust them. If they were nice, I thought, ‘What do they want from me?’ I had to learn for myself how people really were. When I found out all white people weren’t bad, I started to relax around them. It took me a long time. Goody and Pat had a lot to do with that.”

Hagler’s mother, Ida Mae, embraces her son following a 1977 KO win over Mike Colbert at the Boston Garden. (Photo by Stan Grossfeld/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Goody (actual name: Guareno) and Pat (actual name: Pasquale) were partners in a Brockton construction company, and they also ran a boxing gym. Goody, a friend of the revered Marciano, had only recently retired from the U.S. Navy, where he served 20 years in the medical corps and had been a boxing instructor. Had Marciano not perished in the crash of a small private plane in an Iowa cornfield on August 31, 1969, the day before his 47th birthday, his intention was to join brothers Petronelli as a partner in the Brockton gym.

It was in that no-frills gym that Marvin Hagler, just 15 and the loser of a street fight the night before, was to glimpse his eventual destiny with the aid of two men who he came to trust almost as surrogate fathers.

“I like to box. I fell in love with all of the fancy moves,” Hagler said of the gym rats hitting the speed bag, of the thuds they made by pounding the heavy bag, of all the permutations of what boxing aficionados have so long referred to as the sweet science. While curious experimenters sporadically showed up at the gym, more than a few drifted away once they discovered the commitment of time and effort required to become reasonably proficient, not to mention the necessity of developing a high tolerance for pain. Hagler, though, was immediately smitten.

“He had that desire,” said Goody, who was 88 when he died on January 29, 2012. “He’d get a little swollen lip or a black eye and he’d come back the next day. Those are the kids you look for. But you don’t promise ’em nothin’.”

Well, it’s best not to promise the unlikely. But Hagler delivered, as did the Petronellis, who quickly sensed that they had a prodigy with the heart, mind, will and power to develop into something special. Marvin was either 55-1 or 50-2 as an amateur, depending on which figure one chooses to believe, and he was the National AAU champion in the 165-pound weight class in 1973, dominating and then stopping Terry Dobbs in the final.

With the 1972 Munich Olympics already past and the 1976 Montreal Olympics more than three years away, Hagler elected to turn pro shortly after his conquest of Dobbs. His first punch-for-pay outing, for which he reportedly received an insulting pittance of $50, came in the Brockton High School gym against Terry Ryan, whom he knocked out in the second round of a scheduled four-rounder.

Coming up the hard way, slowly and often for meager purses, had the effect of embittering Hagler – a former national amateur champion, after all – when he saw the attention and bigger-bucks opportunities that quickly went to the more celebrated members of the 1976 U.S. Olympic boxing team, particularly future archrival Sugar Ray Leonard.

“I know all I’m going to get is one [shot]. They won’t give me another. I’m too good for my own good.”

“Look at all that money those Olympic kids got; look at all the money tennis players get,” Hagler told the New York Times prior to his third matchup with Sugar Ray Seales, a gold medalist at the 1972 Olympic Games, against whom he went 2-0-1. “Leon Spinks got a title shot after seven fights. Some guys have fought for the title four times. This is my 45th fight and I still haven’t gotten one, and I know all I’m going to get is one. They won’t give me another. I’m too good for my own good.”

It might be argued that getting too much, too soon can spoil certain fighters, blurring their focus and making them overly comfortable with the perks of success. Marvin Hagler never had that problem; he used every real or perceived slight as another log tossed onto the inner fire that raged inside him like a blast furnace.

By the early 1970s, Hagler was the best middleweight in New England. However, that regional stature did little for his campaign to break through to the next level populated by the 160-pound weight division’s true elite. Goody, his trainer, and Pat, his manager, came to the joint decision that Marvin needed a much better grade of opponents to elevate his game. They decided to take him, frequently if necessary, to the great fight town of Philadelphia, which then boasted four of the 10 top-rated middleweights on the planet.

In their third bout, Hagler destroyed Olympic champ Sugar Ray Seales in 80 seconds. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

“All those Philadelphia fighters were tough,” Goody recalled in 1991. “We fought ‘The Iron’ down there. I called them ‘The Iron’ because they were as tough as iron. Whenever we fought one of ’em down there, I’d use the others as sparring partners.

“When we got there, I remember the Spectrum promoter, Russell Peltz, telling me, ‘Guys from Boston (or thereabout) can’t fight.’ But I looked Russell in the eye and said, ‘This one can.’”

Hagler’s first venture into the crucible of the Spectrum ended in disappointment and disillusionment; the visitor from Brockton, who had come in 25-0-1 with 19 KOs, dropped an extremely dubious 10-round majority decision to Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts, the sort of outcome that might have dissuaded another promising young fighter (Marvin was then 21), or his handlers, from any return engagements. Even Philly’s legendarily inhospitable fight fans railed against that obvious injustice.

But return Team Hagler did to the City of Brotherly Love, for more of the sort of on-the-job learning experiences that served the dual purpose of sharpening Marvin’s skills and toughening his resolve. After registering a second-round stoppage of Matt Donovan in Boston, Hagler came back to the Spectrum on March 9, 1976, for a risky 10-rounder with wily, world-rated veteran Willie “The Worm” Monroe. This time there was no controversy; Monroe schooled Hagler in coming away with a wide 10-round unanimous decision victory, the only Hagler non-victory throughout his pro career that was beyond reproach.

In a fight witnessed by only 3,459 spectators because of a crowd-inhibiting snowstorm that also prevented a television crew from being on-site, which explains why there is no film footage of the not-yet Marvelous One’s harshest lesson to that point and maybe ever, he bled from the nose from the fifth round on and both of his eyes were nearly swollen shut by the final bell.

“Marvin thought he was good, but he hadn’t fought the caliber of fighters I had,” Monroe, who was 73 when he died in 2019, recalled in 1987. “He had never fought a seasoned pro. He beat Watts, but he didn’t get the decision. He should have been unbeaten when he fought me.

“I was strong, tall, slick and quick. He couldn’t figure me out. I hit him with a left jab in the first and his eyes opened wide. I beat him with uppercuts, busted a blood vessel in his nose. He bled a lot. Both his eyes were closed. I couldn’t see how he made it through 10 rounds.”

Even in defeat, however, Hagler’s grittiness impressed Monroe’s trainer, former middleweight contender George Benton, who in 2001 was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame for his work with, among others, such greats as Evander Holyfield, Pernell Whitaker and Meldrick Taylor.

“He could have [quit],” the now-deceased Benton said after the fight. “He had opportunities all through the fight and no one would blame him. But he’s one tough kid. He is going to be outstanding.”

Peltz, who said he might then have afforded to sign the unaffiliated Hagler to a promotional contract, wasn’t so certain as to what the future held for someone who was 0-2 in his Philadelphia appearances.

“You learn as you go, but you never stop making mistakes,” a wistful Peltz said of letting Hagler slip through his fingers.

From that tenuous start, however, a rapidly improving Hagler demonstrated that “The Iron” was malleable. He halted Eugene “Cyclone” Hart in eight rounds at the Spectrum in September 1976 and wore down Monroe to a 12th-round TKO in Boston five months later. In August of 1977 and 1978, Hagler stopped Monroe in two (their rubber match) and scored a clear-cut 10-round unanimous decision over Bennie Briscoe, both bouts in the Spectrum. Not only that, but he added a second-round stoppage of Watts in Portland, Maine, in April 1980. That officially made him 5-2 for the gauntlet run against Philly’s finest 160-pound practitioners of the pugilistic arts, and in reality 6-1. Fulfillment of his destiny was now enticingly close.

Hagler’s first fight against Vito Antuofermo would only lead to more frustration. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

Or was it? As a shot at the middleweight title continued to be a hazy apparition, Hagler considered quitting the Petronellis, who had helped him get by financially in the early days of low-purse ring engagements by employing him at a fair wage to do apprentice-level jobs for the Petronelli Construction Company. However, he opted to remain loyal to those who had been loyal to him, rather than to take off for a career recalibration in California.

“Pat and Goody did something for me that they never realized,” Hagler said. “I was grateful to have a trade. They matured me. I found trust in these two people. I kind of knew what I wanted in life.”

After his last pre-title-shot bout against a member of “The Iron” (Briscoe, on August 24, 1978), Hagler was made to wait for five more fights over 15 months until he finally was granted the chance to demonstrate, as he and an increasing number of riders on his bandwagon believed, that he was the best middleweight in the world. That opportunity – in Hagler’s 50th pro outing! – would come on November 30, 1979, against Ring/WBC/WBA champ Vito Antuofermo, who was making the first defense of the titles he had wrested from Argentina’s Hugo Corro five months earlier.

The 15-round split draw, enabling Antuofermo to retain his bejeweled belts, to many appeared to be another miscarriage of justice. A miffed Hagler would have to wait a while longer to sit upon the throne he believed already should have been his. But once coronated, his reign would be long and glorious.