Leonard-Benitez and Antuofermo-Hagler I: A memorable night at Caesars

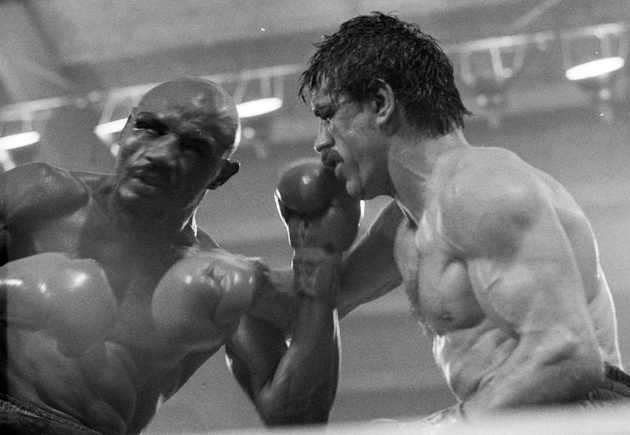

Wilfred Benitez (L), the unbeaten WBC welterweight champ, lays into undefeated challenger and media darling Sugar Ray Leonard during their nationally televised title bout on Nov. 30, 1979. Photo / THE RING

Thirty-five years ago today, boxing observers believed they were about to witness an exceedingly rare event – the coronation of not one, but two superstars.

1976 Olympic gold medalist Ray Leonard – nicknamed “Sugar” for the superlative skills that mirrored those of Sugar Ray Robinson – was a solid 3-to-1 favorite to dethrone WBC welterweight titlist Wilfred Benitez while consensus number-one challenger Marvin Hagler was a 4-to-1 choice to unseat undisputed middleweight champion Vito Antuofermo.

The story lines seemed so right and so brilliantly positioned. Leonard, already a megastar thanks to his Olympic success and frequent appearances on terrestrial TV, appeared poised to become the new face of boxing, a mantle held so long by the soon-to-be-retired Muhammad Ali. Leonard had it all – a megawatt smile, a TV-friendly personality, brilliant all-around skills and a pristine 25-0 (16 knockouts) record.

Leonard’s rise to this day of destiny not only was the result of his incandescent talent but also the keen guidance of chief second Angelo Dundee. The trainer who molded the likes of Carmen Basilio, Luis Rodriguez and Jose Napoles used his decades of experience to match Leonard against a wide variety of styles – tough guys, southpaws, cuties, fringe contenders, naturally bigger men and recent contenders. Leonard passed every test and scored plenty of style points along the way. The result of Dundee’s handiwork came together in his most recent fight against Andy Price, which ended just 172 seconds after it began thanks to a breathtakingly explosive flurry. The Price victory was particularly significant because, until recently, the Californian’s main claim to fame was that he held decision victories over the two reigning welterweight champions — the WBA’s Pipino Cuevas and the WBC’s Carlos Palomino. While Cuevas still had an iron grip on his bauble, Palomino couldn’t say the same because in January he was upended by the man Leonard was about to face – Benitez.

Hagler’s trip toward the top was much longer and more difficult than Leonard’s, and that rougher path seemed to suit his blue-collar persona. Like another famous resident of his adopted hometown of Brockton, Mass., Hagler had fought 49 times to date. Unlike Rocky Marciano, however, Hagler’s record was blemished (46-2-1, 38), mostly because he was willing to fight in his opponents’ hometown. The first blot, a 10-round draw to another Sugar Ray – Sugar Ray Seales – took place in Seales’ home turf of Seattle while the two losses came against two members of what Hagler called “The Iron” of Philadelphia, a questionable majority nod to Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts and a definitive points decision to Willie “The Worm” Monroe. Hagler avenged all three imperfections in terrifying fashion: He crushed Seales in one round in their third and final meeting (Hagler decisioned him in fight one) and blasted out Watts (KO 2) and Monroe (KO 12, KO 2) with similar venom.

His shaven skull, goateed face, rock-hard physique and intimidating aura was exceeded only by his dazzling talent inside the squared circle. Moving about on perpetually springy legs, the cerebral Hagler picked opponents apart with spearing jabs, lancing left crosses and robust body shots that, more often than not, set up the final knockout drops. Moreover, Hagler was truly ambidextrous; the natural right-hander fought best as a southpaw and he executed every blow from both stances with fluidity and textbook execution.

Not only did Hagler look tough and fight tough, he talked tough and he acted tough.

“Talk to me now, but you’d better make it quick ’cause tomorrow not even my mother will be able to,” he’d say two or three days before a fight. He refused to shake hands with opponents at contract signings or press conferences and if he touched gloves with opponents just before the bell, he did so grudgingly. Hagler’s thirst for success was unquenchable and only his maniacal training habits in the solitude of his Provincetown, Mass. training camp were able to properly channel his inner drive.

He felt his first shot at the middleweight championship should have happened several years earlier and he made no bones about expressing his frustration publicly. He screamed for Rodrigo Valdes to give him a shot, then directed his fire at Hugo Corro when he upended Valdes. Hagler was promised his long-awaited crack against the winner of Corro-Antuofermo should he defeat Norberto Cabrera on the undercard. After Hagler forced Cabrera to retire on his stool after eight rounds, Antuofermo stunningly lifted Corro’s title by razor-thin split decision.

That result forced Hagler to shift his ire toward Antuofermo, who he dubbed “Vito the Mosquito” due to his 5-foot-7¾ height. During the build-up Hagler wielded a fly-swatter and everywhere he went he promised to squash Antuofermo like a bug. And why wouldn’t he think that way? After all, he had won his last 20 fights, 18 by knockout.

Antuofermo, however, was no insect but rather a rugged, durable and fearless competitor whose ring style mirrored that of one of his former professions – sausage grinder. At his best, Antuofermo used his arms, elbows and shoulders to burrow into point-blank range where his short punches and indomitable will tilted the balance of power. Beside Corro, his best wins going into the Hagler fight included perennial contender Bennie Briscoe (W 10), Eugene “Cyclone” Hart (KO 5), Emile Griffith (W 10), former junior middleweight champion Denny Moyer (W 10) and future 154-pound king Eckhard Dagge (W 15), who won his belt just five months after losing to Antuofermo. Heck, Vito even had a near-shutout decision in Madison Square Garden over a fighter named John L. Sullivan in March 1974.

His squat, powerful build didn’t produce many knockouts (19 in his 45-3-1 record) and his tireless aggression exacerbated his biggest weakness – tissue-thin skin around the eyes. Severe cuts led to his first defeat against Harold Weston six years earlier and even in victory he bled as if he had just worked a shift in the slaughterhouse. The conventional wisdom going into the Hagler fight was that if the challenger didn’t stop Antuofermo outright, he’d lose his titles on cuts.

As ugly as Antuofermo’s style was to watch for some, that’s how pretty Benitez’s was. The Puerto Rican was boxing’s version of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, a God-gifted genius that excelled at the top levels at an absurdly young age. Just two-and-a-half years after turning pro at age 15 Benitez became boxing history’s youngest world champion when, at age 17 years 180 days, he dethroned not only a titlist but longtime WBA junior welterweight king Antonio Cervantes, a future Hall of Famer who had fought 86 times and made 10 successful title defenses. Fighting before an audience that included several of his high school classmates, Benitez scored a split decision that stunned the boxing world.

Benitez proved he was no flash-in-the-pan as he defended his belt twice against Emiliano Villa and Tony Petronelli before the WBA stripped him for not granting Cervantes a rematch. Three years later Benitez, still only 20, won his second divisional championship by beating another long-reigning titlist in Palomino, again by a split decision that should have been unanimous. There, he showed all the skills that earned him raves – dizzying hand and foot speed, extraordinary upper body movement, pinpoint counterpunching and state-of-the-art ring generalship.

Given all of Benitez’s gifts, why was he an underdog to Leonard? First and foremost, the odds were a tribute to Leonard’s immense talents, which were more complete than Benitez’s. Second, Benitez’s chin was of questionable constitution. He suffered three knockdowns in his first fight against Bruce Curry (W 10), and had the fight not been scored on the rounds system he would have lost. Third, and perhaps most crucially, as mature as Benitez seemed inside the ring, he was the polar opposite outside it. His training time for even the most important fights was measured in days, not weeks, yet he still managed to make weight and perform when it counted most. His demeanor was so scattered that some thought him to be mentally challenged. The child-like Benitez couldn’t even settle on a single nickname – he alternated between “Radar,” “The Dragon” and “The Bible of Boxing.” Finally, although he had 25 KOs in his 38-0-1 record, most of those occurred during the record-building phase of his career. Including the Cervantes bout, his introduction to the world-class stage, Benitez had scored only five knockouts in his last 14 fights.

Once the quartet made weight (158¾ each for Antuofermo and Hagler, 146 for Leonard and a stunningly light 144¾ for Benitez), the stage was set for a most memorable night of boxing.

To illustrate just how much the television landscape has changed over the years, these two fights – along with the WBA light heavyweight title fight in New Orleans between champion Victor Galindez and former titlist Marvin Johnson – was aired on ABC during prime-time. Today, fights with the pedigree of Leonard-Benitez and Antuofermo-Hagler I would most likely top separate pay-per-views, for Benitez was an unbeaten champion defending against his most magnetic challenger in terms of accomplishments and media appeal while Antuofermo was risking his belt against the unquestioned number-one challenger in the second most glamorous weight class behind heavyweight. The fact that a fight for the undisputed middleweight championship was the lead-in to a light-heavyweight contest staged 1,800 miles to the southeast and a welterweight title fight illustrated just how special this broadcast was – and would end up being.

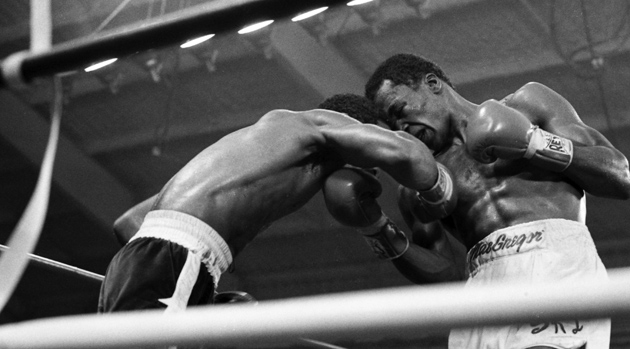

Strategically, Antuofermo-Hagler I began as expected with the naturally right-handed challenger popping southpaw right jabs while executing subtle shoulder feints and the Italian-born Brooklynite barreling in behind body shots and straight rights. A quick counter left cross briefly buckled Antuofermo’s legs late in the first and a double-left early in the second also earned the champion’s notice. Hagler took advantage of the large 19¾-foot square ring by constantly circling, scoring his points and getting out before Antuofermo could adequately answer. During those rare times Antuofermo worked his way inside, referee Mills Lane made sure the infighting didn’t devolve into grappling.

Photo / THE RING

Starting in round three Hagler began the switch-hitting tactics that proved so successful throughout his career. He soon proved to all that he could hit the champion whenever and from wherever angle he pleased. His piercing punches landed like a bullfighter’s sword and it was clear they soon would inflict damage on Antuofermo’s vulnerable face. Hagler’s slicing crosses created a bruise under the right eye, the first, but not certainly the last, injury Antuofermo’s face would incur.

In round four, Hagler opened a cut over Antuofermo’s left eye and in the corner between rounds the champion could be heard coughing thanks to a case of bronchitis.

Urged to bull his way inside and rough up the challenger, Antuofermo said, “I’ll go get him now.”

The champ was as good as his word as he changed out of the corner and immediately got into close quarters. He nailed Hagler with an overhand right to the chin, his first serious connect of the bout. He mauled and brawled more effectively and a series of pelting punches forced Hagler to give ground time and again. It clearly was the champion’s best round thus far.

Stung by Antuofermo’s sudden rally, Hagler turned up the volume in the sixth. He rattled the champion’s head with jolting jabs and snappy combinations delivered from both stances. Those blows opened two additional cuts, one near the bridge of the nose above his right eye and the other below the same eye, an area which also was puffy.

The seventh alternated between Hagler’s pretty boxing and Antuofermo’s determined slugging and the result was constant action and plenty of punishment.

Most observers had Hagler well ahead at the half-way mark but starting in round eight Antuofermo began cutting the distance, both physically and mathematically. While Hagler still scored his share of points his near-monopoly no longer applied. Antuofermo continually charged in behind clubbing blows thrown with deceptive speed and accuracy. They didn’t hurt Hagler but they landed frequently enough to make an impact.

Antuofermo picked up the energy even more in the ninth and his hacking hooks and crosses shared billing with Hagler’s stiletto jabs and flush counters. Antuofermo’s defense also was improved as he ducked under a wild right and weaved under several more threatening blows. Slowly, but surely, the champion was working his way back into the fight and in doing so it brought into question the only Hagler asset that had yet to be fully tested – his stamina. While Antuofermo had that in spades, Hagler had only fought past 10 rounds twice to date. He won both – one by knockout – but no one, even Hagler, knew how he would fare in a hard 15-rounder.

One had to wonder, however, if Antuofermo’s face would hold up long enough to draw Hagler into those deep waters. Following round nine the champion sported a complete set of cuts – one above and below each eye – and there were still 18 minutes of action remaining. The good news for Antuofermo was that his chief second was the venerable Freddie Brown, an expert cut man if ever there was one.

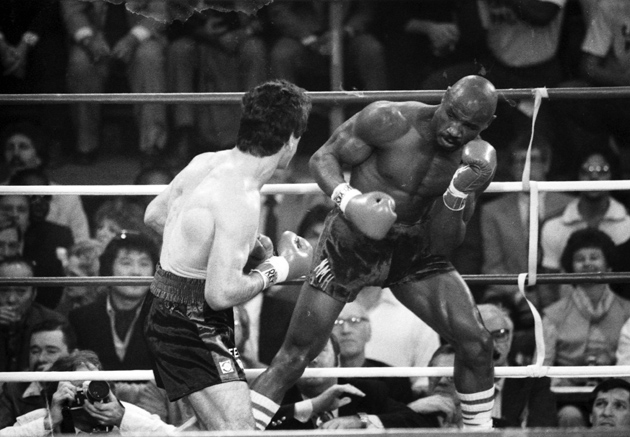

As the fight swung into the double-digit rounds, however, the fight’s tone favored Antuofermo’s grit over Hagler’s gifts. Hagler’s punch output dropped as Antuofermo’s pressure rose, and though the challenger continued to work hard his effort lacked its earlier sharpness. Like it or not, Hagler was hurtling head-long into Vito’s Valley – rounds 11-15.

For Antuofermo it was a repeat of the Corro fight – a slow start followed by a fast finish, and there he won an unlikely middleweight championship. Now, exactly five months later, history was working in his favor.

Antuofermo, clearly feeling the momentum had swung his way, flew out of the corner with renewed energy, bulled Hagler to the ropes and worked with unquestioned vigor. Within the context of his style Antuofermo had found his rhythm and because of that he seized upon whatever tiny openings Hagler presented. The action wasn’t one-sided by any measure, but the gap that had been so obvious in the early rounds had all but closed. The final half of the 11th featured the most sustained two-way action of the bout thus far and the Caesars Palace crowd responded with sustained roars.

The pitched battle continued in the 12th as Hagler sought to regain control by standing his ground and firing combinations in order to force Antuofermo to back up. Antuofermo responded by weaving away from whatever he could, then charging in behind hooks to the head and body. A stunning right-left-right nailed Hagler later in the round.

“Just as Hagler was reasserting command this tough little cookie who doesn’t want to lose his title came back and landed three crisp, sharp blows that stung Hagler,” ABC’s Howard Cosell marveled. “It’s amazing the way that little fellow, Antuofermo, will strike back at you.”

But would he strike back often enough to save his title?

Thanks to his corner’s masterful work Antuofermo’s cuts were largely neutralized. And thanks to his busy work rate and unlimited courage he had worked his way back into the fight. Hagler, still in command of the majority of his skills, had receded just enough to give the champion the opening he needed. The 13th saw plenty of infighting, Antuofermo’s specialty, and Hagler missed much more punches than at any time in the fight. A whizzing right along the ropes appeared to stun Hagler, who spun off the ropes and danced not for strategic purpose but to clear his head. An emboldened Antuofermo, remembering all the taunts Hagler hurled at him during the buildup, beckoned Hagler in, then whacked him with a right to the ribs and a hook to the jaw as the crowd went wild.

Hagler tried to regain control in the 14th but Antuofermo was now in the zone. He got close enough to the challenger to establish proper range yet found a way to strike without being tied up. Worse yet for Hagler, a stray head opened a cut over the right eye. As Hagler’s corner implored for him to put his punches together, Hagler did just that by hurting Antuofermo with a solid right midway through the round. But the champion quickly shook off the blow and kept coming with his short-armed but accurate blows.

With blood flowing from both men’s faces, the 15th round was a free-for-all as each emptied their respective tanks. This was a purely defense-optional round as both focused on making their best final statement. Hagler’s jolting uppercuts and fierce second-minute surge appeared to carry the round – and in most minds, the fight.

At the bell both men threw their hands in the air, and once the scorecards were announced both men’s arms remained in the air.

Duane Ford saw Hagler a 145-141 winner while Dalby Shirley voted 144-142 for Antuofermo. Hal Miller cast the deciding ballot – 143-143, a draw that allowed Antuofermo to keep his title.

“All this does is add to the bitterness in me,” an infuriated Hagler said. “But I’m going to keep it there, because it will make me even meaner and tougher and inspire me to work even harder. In my heart, I believe I am the middleweight champion. But this has taught me that I got to go in and knock out every man I fight in order to win.” Hagler made good on his promise, for he would go on to knock out his next eight opponents and 12 of his next 13. The only decisions he would face the rest of his career: A razor-thin verdict over Roberto Duran and a hotly disputed split decision against his card-mate, Sugar Ray Leonard.

“The draw does not make me happy, but I’m very happy that I kept my title,” Antuofermo said. “I thought I won the fight, even though he confused me with his switch-hit style. I don’t want to make any excuses, but I had a bad case of bronchitis, and Hagler himself can tell you I was coughing throughout the fight. Sure, I’ll give him a rematch. And next time I’ll be in better shape. I’ll keep on top of him more, so there won’t be any question who really won the fight.”

Observers may dispute the result of Antuofermo-Hagler I, but one fact that can’t be denied was that it was a far better fight than anyone ever could have hoped.

*

ABC switched its coverage to the Superdome in New Orleans, where the fast-starting Johnson became the third man to regain a portion of the light heavyweight championship by flattening the second man to do so. Johnson, who lost his WBC belt to the soon-to-be Matthew Saad Muhammad two fights and seven months earlier, ended the contest early in the 11th when a smashing overhand left Galindez sprawled on the canvas. The blow broke Galindez’s jaw and closed the curtain to what eventually would be a Hall of Fame-caliber championship run for the Argentine. For Johnson, it was vindication against critics that questioned his stamina because his excellent work rate sustained itself until his final blow.

Once the final bows of Johnson’s victory were tied, the network returned to Caesars to cover Leonard’s first attempt at world honors and Benitez’s efforts to fend him off. The final stare down was particularly intense as Benitez radiated an air of confidence and superiority while Leonard admittedly failed to match that intensity.

“Benitez was trying to establish a tone so that I would be more wary of him once the bell rang,” Leonard wrote in his autobiography The Big Fight. “Prizefighters since John L. Sullivan in the late 1800s had played these mind games all the time. In this case, there was reason to believeit might work. As we stood only inches apart, I was the one who appeared tentative. I needed to recover – and fast.”

Unlike the brute force that marked Antuofermo-Hagler I, Leonard-Benitez was boxing’s version of elite chess. Each move was designed to set up actions several seconds down the line and one could almost see the wheels turning in both boxers’ heads. They executed feints with the head, shoulders and feet while circling or stalking, probed with their jabs and fired their hardest punches only when they were convinced they would land. Of course, most of them didn’t because their respective radars were operating at full capacity.

Over the long haul Leonard scored more often but even then his points came one at a time instead of the beauteous bouquets that bedazzled past opponents. An example: Midway through the first Leonard connected with a scorching hook but his next eight punches found nothing but air thanks to Benitez’s amazing upper body movement and sense of anticipation. Benitez repeatedly ducked under Leonard’s windmill overhand rights but because he failed to mount his own steady offense Leonard built a growing lead on the scorecards. By doing so, Leonard proved to all that he not only was physically superior but also capable of out-thinking the most cunning strategists.

Leonard’s first major breakthrough occurred with 27 seconds remaining in round three when a shotgun jab sent Benitez crashing to the floor. That knockdown was evidence of Sugar Ray’s impeccable timing, for he nailed Benitez at the very moment his feet were parallel. Up at two, a sheepish Benitez shrugged his shoulders as he walked toward the neutral corner while Leonard wore a confident half-grin as he observed referee Carlos Padilla’s count.

While given to showmanship in previous fights, Leonard was all business as he continued to scan and strike amidst a boxing rarity – an entertaining think-fest.

An accidental clash of heads opened a cut in the center of Benitez’s forehead in the final minute of round six and for the remainder of the fight it produced a stigmata-type flow. Tasting his own crimson, Benitez lashed out with his most robust attack of the fight but most of the blows only found air as Leonard calmly avoided the blows while delivering several of his own pinpoint shots.

Benitez tried to goad Leonard into exchanging early in the seventh but the challenger wisely had none of it. Even when Benitez dropped his left hand to his thigh Leonard refused to take the bait. He remained devoted to his scientific blueprint and as a result he continued to reap the rewards – a string of 10-9 rounds.

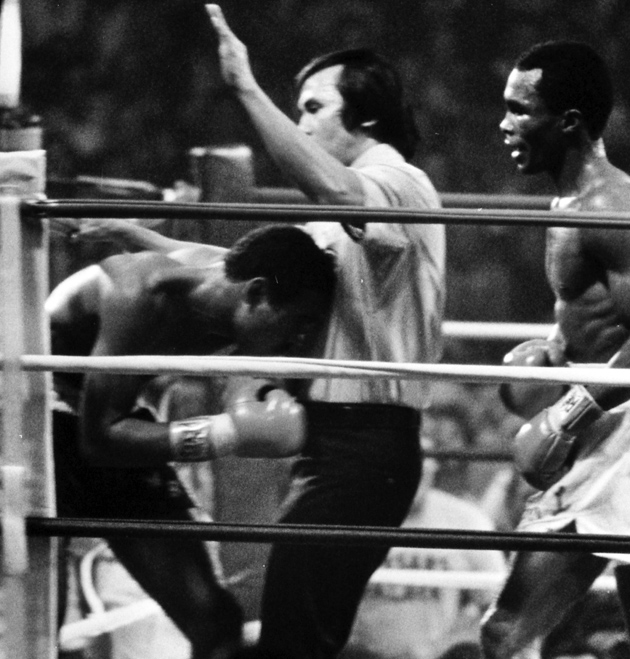

Entering the final round Leonard led on all three cards, though by varying margins. Art Lurie saw a resounding 137-130 margin while Harry Gibbs saw a much closer battle at 136-134. Ray Solis was in the middle at 137-133. Nevertheless, the math indicated Benitez needed a knockout to keep his belt. Yes, the fight would end by knockout, but it was the man who had the points to spare that scored it.

Photo / THE RING

With 31 seconds remaining Leonard landed a left uppercut and a grazing hook to the temple that caused Benitez’s legs to collapse in sections. Up again at two, Benitez shook his head and tottered toward the corner to collect his thoughts. Padilla allowed the fight to continue but after a six-punch flurry that mostly missed the arbiter waved off the fight with just six seconds remaining on the clock. The most heartbroken person in the building – even beyond the dethroned Benitez – was gambler Billy Baxter, who lost a $150,000 bet that the fight would go the full 15 rounds.

“Now I know I have another boxer like me, a good champ,” a classy Benitez said after the fight.

Leonard agreed in his assessment of Benitez.

“I feel that he’s a great champion and I knew he had a lot of experience,” he told Cosell. “But I wanted the belt so bad. He hurt me with a good left hook. One time we butted heads and that got me a little dazed but I was so determined. This is the greatest moment of my life other than Montreal.”

Leonard, always the keen observer, took a lesson from the Antuofermo-Hagler fight.

“I knew I had to pull it out because I saw the dynamite fight between Hagler and Vito Antuofermo,” he said. “I knew I had the edge and I felt I had control, a couple of rounds I gave to him because he did show me that he had the experience of a great champion. I really feel great that I can go home with the belt around my waist.”

There would be more belts wrapped around Leonard’s waist but no fighter ever forgets the first.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 12 writing awards, including nine in the last four years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.