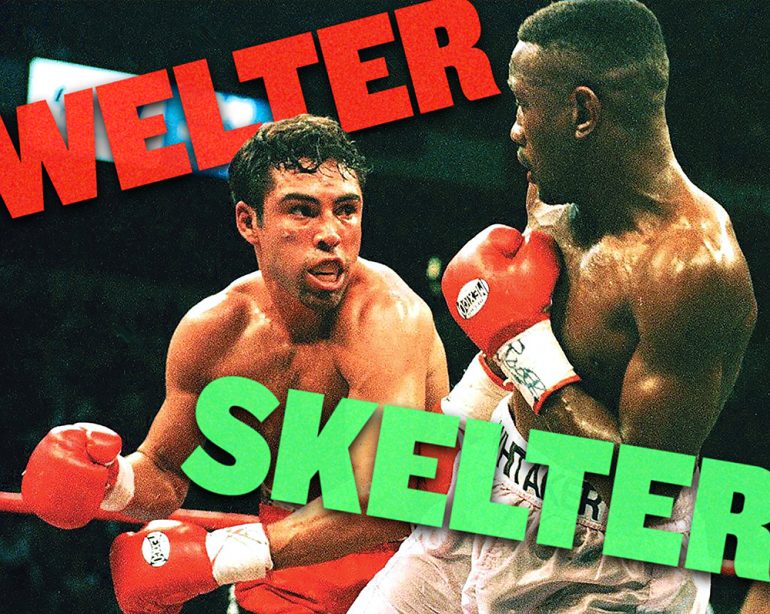

Welter Skelter

Twenty five years ago, on this day (Dec. 6), Oscar De La Hoya capped a banner year with an eighth-round stoppage of respected contender Wilfredo Rivera. The year, which began with a defense of the WBC 140-pound title against undefeated (41-0) Miguel Angel Gonzalez, marked his anticipated move to welterweight.

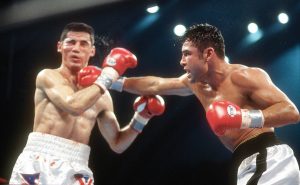

Oscar De La Hoya nails Wilfredo Rivera during his defense of the WBC and lineal welterweight titles on December 6, 1997 at the Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images

De La Hoya’s foray into the glamorous 147-pound division would start with a challenge to the legendary Pernell Whitaker. After passing the sternest of boxing tests, The Golden Boy stayed busy while working his way to showdowns with his fellow unbeaten welterweight peers, Ike Quartey and Felix Trinidad. Sadly, given the current state of the boxing world, fans may never see another world-class fighter (let alone a superstar) fight five times in the same year as De La Hoya did in 1997.

The following article, penned by Cliff Rold, was originally published in the September 2022 issue of The Ring magazine, celebrating De La Hoya’s career (a special edition that recently sold out at the Ring Shop).

DE LA HOYA’S MOVE TO 147 POUNDS DURING A FIVE-FIGHT RUN IN 1997 WOULD CEMENT HIS STATUS AS THE STAR HE WAS ALWAYS EXPECTED TO BECOME

Sometimes, honesty can bite back.

Even if it really is the truth.

On the eve of Oscar De La Hoya’s move to welterweight to challenge WBC and lineal welterweight king Pernell Whitaker, “The Golden Boy” was asked if the judges might favor him against one of the aging greats of the sport. De La Hoya gave USA Today an honest reply.

“I think so. Unfortunately, that’s boxing … It’s all politics, it’s all about money. What the WBC sees is that I’m a young fighter. If I win the title, I obviously make more money than Whitaker or anybody else.”

Entering 1997, the hope throughout the sport of De La Hoya becoming a sort of Sugar Ray Leonard 2.0 was coming to pass. De La Hoya had seized the torch from Mexican icon Julio Cesar Chavez as the new lead star of the lighter weight classes in 1996. Affiliated with HBO, De La Hoya’s rising star gave the network a fresh face to build around while Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield were affiliated with Showtime.

De La Hoya would engage in five fights in 1997, four of them on pay-per-view, cementing his place as the biggest non-heavyweight draw in the game. The biggest of those pay-per-view outings would give Oscar a chance to knock off his second living legend in less than a year. It didn’t go as well as the win over Chavez in the ring but did little to stop his ascension as a star.

Before he got there, De La Hoya opened the year on January 18 against a fighter who had once been labeled as a potential heir to Chavez. Mexico’s Miguel Angel Gonzalez was undefeated at 41-0. From 1992-1995, Gonzalez reigned as WBC lightweight titleholder and made 10 defenses (in addition to a pair of non-title fights) before a move to junior welterweight, where he would challenge De La Hoya for the WBC crown.

De La Hoya decisively handed Gonzalez his first defeat. Mark Jacobs wrote for The Ring, “The Gonzalez fight proved an entertaining, if mostly one-sided, tune-up. From the start, De La Hoya … dominated with a wicked jab, popping the punch into the center of Gonzalez’s face and repeatedly snapping back the Mexican’s head.” Gonzalez would lose two points on fouls in a fight where he won only the third, ninth and 10th on the cards with two judges calling the 11th round even.

The business of the bout was pretty good for a tune-up, capturing nearly 350,000 buys.

De La Hoya’s win over Gonzalez ended his brief run at junior welterweight and set the stage for another showdown with boxing’s old guard elite. But De La Hoya-Whitaker almost died on the launchpad six days later.

“Sweet Pea” had shown signs of decline in 1996, struggling in two bouts with tough Wilfredo Rivera. It was nothing compared to the drama when Whitaker squared off with unheralded challenger Diosbelys Hurtado.

“Sweet Pea” had shown signs of decline in 1996, struggling in two bouts with tough Wilfredo Rivera. It was nothing compared to the drama when Whitaker squared off with unheralded challenger Diosbelys Hurtado.

Fighting with no fear, Hurtado was quicker and more explosive than Whitaker early. The Cuban dropped Whitaker moments into the first and then again in the sixth, building a lead on all three scorecards entering the 11th round. In a finish reminiscent of Jake LaMotta-Laurent Dauthuille II, Whitaker found a ferocious assault when he needed it. The defensive wizard pummeled Hurtado into submission to save his title and a significant payday with The Golden Boy.

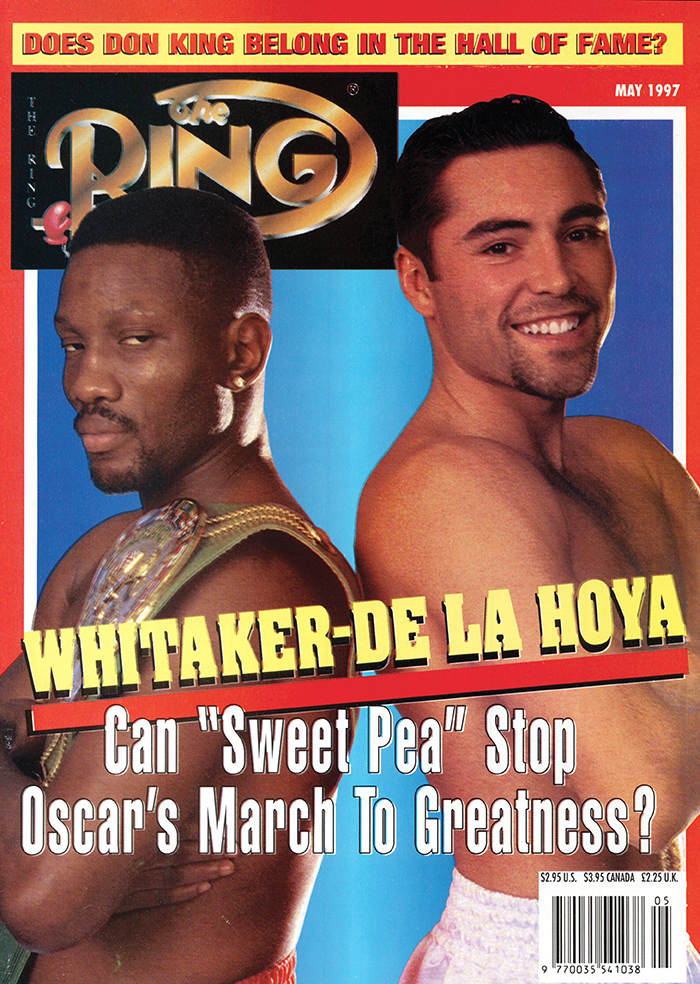

The Hurtado fight raised serious questions. At 33, did Whitaker still have it in him to tackle the youth and firepower of De La Hoya? There was a superfight in place to find out.

“Superfight” is a reference to the event more than the action that followed on April 12, 1997. The styles of Whitaker and De La Hoya didn’t generate explosions, though it was a fascinating technical encounter. Whitaker lost a point under WBC rules for a cut caused by an accidental butt, a rule since discontinued in the United States. De La Hoya suffered an awkward but official knockdown in the ninth.

Between those moments, Whitaker got the better of the statistical battle by outlanding De La Hoya 232-191 on the night, according to CompuBox. Of Whitaker’s scored blows, 160 were jabs while De La Hoya’s total included only 45 leads. There were several moments in the bout where De La Hoya would flurry frantically and find nothing but the air around Sweet Pea. Missing for those who preferred De La Hoya’s aggression was substantial return fire from Whitaker.

Was De La Hoya’s aggression effective? Could the scoring components of defense and ring generalship decide a contest where offense felt fleeting? The judges came in unanimously for De La Hoya. Opinion beyond their pencils was split.

Debate about the outcome started as soon as the scores were read. It remains a debated finish to this day among fight aficionados. ESPN covered the fight live by providing viewers who had not purchased the pay-per-view with their unofficial scoring between rounds. It’s a feature some networks used to provide on big fight nights in another era. ESPN scoring favored Whitaker.

The HBO commentary team was split throughout the night, with Jim Lampley favoring De La Hoya’s work while Larry Merchant and Roy Jones seemed to like the work of Whitaker.

Read “Whitaker-De La Hoya, 20 Years Later”

Most saw a close fight. The judges did not at 116-110 twice and 115-111. Notably, Whitaker’s only winning round on all three scorecards in the second half of the fight came in the ninth by way of the aforementioned awkward, uninjurious knockdown in the frame.

Scoring of some key rounds, notably the first and 11th rounds, raised eyebrows. Whitaker got the nod from only one judge in each frame. According to the live CompuBox tallies on the broadcast, Whitaker outlanded De La Hoya 17-11 in the round and drew blood from De La Hoya’s nose. Discussing the fight for an in-studio replay on HBO, Merchant opined, “If Pernell Whitaker didn’t win that first round from all of the three judges, or later the 11th round, I think we know that going into the fight, for whatever reasons – reasons of style, reasons of glamour – [Whitaker] had to win that fight by a knockout.”

Those who favored Whitaker on the night probably couldn’t help but factor the sentiments De La Hoya voiced prior to the fight. … It’s all politics, it’s all about the money. Unrealistically lopsided scores in favor of De La Hoya fueled cynicism among those who scored the bout for Whitaker.

Those who favored Whitaker on the night probably couldn’t help but factor the sentiments De La Hoya voiced prior to the fight. … It’s all politics, it’s all about the money. Unrealistically lopsided scores in favor of De La Hoya fueled cynicism among those who scored the bout for Whitaker.

Writing for Sports Illustrated, Richard Hoffer reasoned that “it required the heightened paranoia of boxing writers and commentators to suggest that the victory was the result of a conspiracy or, for that matter, anything but the natural forces that replace old with young, traditional with modern. The fight was close, without conclusive volleys, and probably featured a little more of Whitaker’s exaggerated sense of artfulness than anybody needed (and a lot less of De La Hoya’s firepower than everybody else wanted). The bout was certainly not a 9-3 or a 9-2-1 affair, which is how two of the Nevada judges scored it (the third had it 8-4, also for De La Hoya), but neither was it robbery. It was just a tough fight that De La Hoya won, barely.”

Or lost, barely.

It depended who one asked. It still does. Ring Magazine’s post-fight coverage, provided by Steve Farhood, favored Whitaker 114-113, as did a rough majority of ringside reporters. Bernard Fernandez, writing for sister publication KO, favored De La Hoya 115-113.

Writing for International Boxing Digest, the legendary Budd Schulberg may have summed it up best: “Ringsiders who consider themselves experts in the arcane art of judging a contest of fisticuffs will be arguing the round-by-round scoring of their bout until both those performers with 180-degree contrasting styles are ready for their Social Security benefits well into the next century. No one truly knows who won this anticlimactic, sometimes lackluster but technically interesting engagement.”

Schulberg acknowledged, in judging the fight from home, he narrowly favored De La Hoya the first time but preferred Whitaker by a hair when he watched it again the next day. It was the sort of fight that could make even seasoned eyes debate themselves.

Regardless of the action in the ring, the bout was a financial windfall, generating over 700,000 pay-per-view buys. De La Hoya said he would take a rematch. It never came to pass, with promoter Bob Arum referring to it as a “stinking fight” in the aftermath. There was other business to do, and the De La Hoya express remained on the rails. Activity against more favorable styles was there to act as a salve against any lingering controversy.

Read “Best I Faced: Pernell Whitaker”

Boxing media was ready to embrace The Golden Boy regardless. De La Hoya moved to No. 1 in the Ring and KO Magazine pound-for-pound lists off the Whitaker win, passing by Roy Jones, and would remain there until his narrow loss to Felix Trinidad in 1999. De La Hoya finished first in KO’s annual “best of the best” media poll for all of 1997 as well.

De La Hoya would also feature at No. 1 in the annual KO Magazine 100. The status report for De La Hoya read: “The Golden Boy has proved his class by fighting class. True, his decision victory over Pernell Whitaker didn’t exactly remind anybody of Dempsey-Willard. But so what? ‘Sweet Pea’ makes everybody look bad. Miguel Angel Gonzalez was no joke either. By comparison, after 24 fights, Sugar Ray Leonard had yet to win his first world title. Oscar’s already won three.”

Left out of that analysis was that Leonard’s first 24 fights came in just his first 2½ years as a professional, but such is the excitement stars can generate. Jones, widely viewed as the biggest talent of his generation after a win over James Toney in 1994, had come into criticism for his opposition following a disqualification loss to Montell Griffin, which created some justification to shake things up in mythical polls.

The Whitaker win still wasn’t the sort of affair boxing fans were looking for from De La Hoya. For the first time, De La Hoya had gone the distance in consecutive fights.

As if to remind fight fans of the excitement he could offer, De La Hoya’s next fight moved to HBO’s regular programming. He changed trainers for the contest as well, aligning with offense-minded Kronk impresario Emanuel Steward. Challenger David Kamau had lost only once, lasting the distance with Chavez in 1995. On June 14, 1997, De La Hoya smoked Kamau in just two rounds, finishing the matter with his patented left hook.

De La Hoya finished David Kamau in two rounds. (Photo by Matthew Stockman /Allsport)

Then it was back to pay-per-view and the big-name veterans pool. Hector “Macho” Camacho had been more sideshow than superstar for several years by then, but a knockout of a comebacking Ray Leonard earlier in the year opened the door for a viable pay-per-view showdown. Camacho was 63-3-1, 35 years old, and brought at least one element the fight could sell on. Despite vicious beatings in losses to Chavez and Felix Trinidad, Camacho had never been stopped. Could De La Hoya be the first to pull it off?

Call your local cable provider to find out.

The answer was “no” in a fight where Camacho came to hear the final bell and little else. The September 13 contest was billed as “Opposites Attack.” De La Hoya did almost all of the attacking, hurting Camacho early and leaving the veteran to clinch incessantly. Camacho was docked a point for the holding in the final round but made it all the way there. De La Hoya scored a knockdown in the ninth and won every round on two scorecards, but he couldn’t put Camacho away.

No boxer ever did. It didn’t matter. The fight did north of 550,000 buys on pay-per-view.

The marriage between Steward and De La Hoya seemed to be clicking after two fights. Previous trainer Jesus Rivero was more defensively focused. Steward saw a more dangerous man to mold. Bernard Fernandez recounted in KO following the Camacho fight that Steward said, “Look at his eyes. He’s the most competitive fighter I’ve ever seen. He’s not content just to win. He wants to be sensational. When he goes into the ring, he’s in his glory. He loves the excitement of a big fight. Before the Kamau fight, I said, ‘You really love this, don’t you?’ And he said, ‘You’d better believe it.’”

Steward would be replaced before De La Hoya’s 1997 finale by another veteran sage, Gil Clancy. Oscar’s corner at least retained the consistency of trainer Robert Alcazar, who had been with De La Hoya since the amateurs. If the constant changes to the lead voice was affecting De La Hoya, there was little evidence against his next challenger, Wilfredo Rivera.

“[Oscar is] the most competitive fighter I’ve ever seen. He’s not content just to win. He wants to be sensational.”

– Emanuel Steward

Rivera had scored four consecutive knockouts since his close losses to Whitaker. The Puerto Rican contender had never been stopped as a professional. That was about to change.

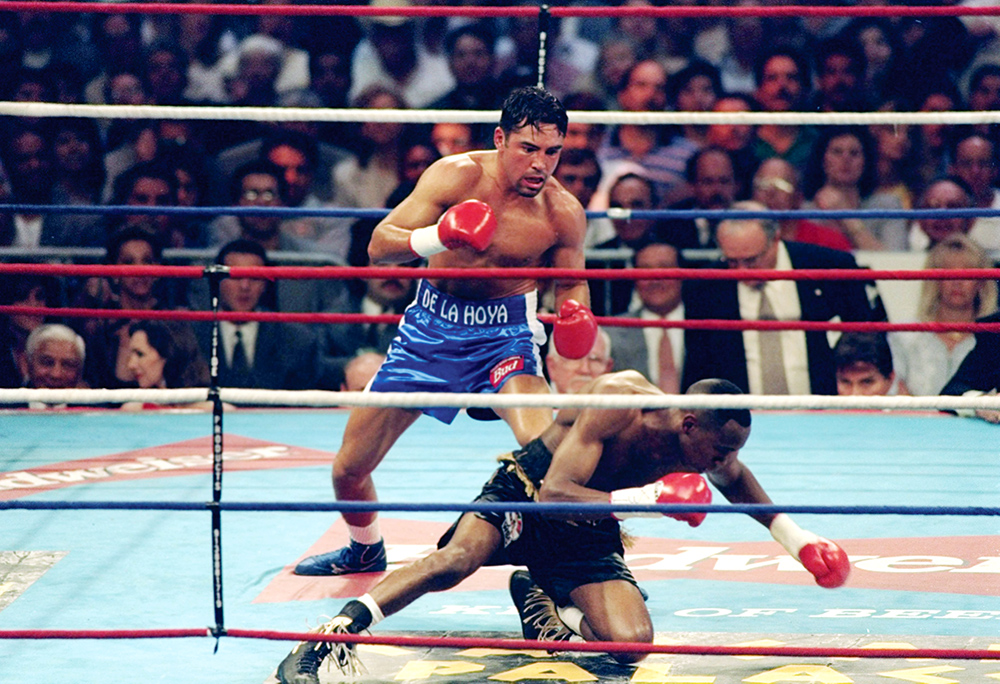

Covering the fight for the Los Angeles Times, Steve Springer recounted, “World Boxing Council welterweight champion Oscar De La Hoya made sure it never came down to the scorecards, made sure there was no repeat of a controversial loss by George Foreman last month in [New Jersey] by slashing open the eye of challenger Wilfredo Rivera in the second round of Saturday night’s title fight at the Atlantic City Convention Hall. From then on it was not a matter of if, but when. Rivera, with blood streaming down the right side of his face for most of the remainder of the match, fought gamely, but ineffectively until ringside physician Howard Taylor finally stopped the fight at 2:48 of the eighth round before 11,271, improving De La Hoya’s unbeaten mark to 27-0 with 22 knockouts.”

De La Hoya scored a knockdown in the fourth and successfully defended his welterweight title for the third time. It was his least successful pay-per-view show of the year, bringing in less than 240,000 purchasing homes, but as part of an overall tally for the year it was hard to miss a bonanza. De La Hoya ended the year at 5-0, scored two knockouts, and tabbed just shy of 2 million PPV buys along with millions in gate revenue.

Boxing had the superstar it thought it might when The Golden Boy came home from the 1992 Olympics with gold. 1997 was the year that stamped it beyond doubt … but hardcore boxing fans were starting to notice who wasn’t on the other side of the ring.

Chavez in 1996, Whitaker and Camacho in 1997 … they were already receding into boxing’s past. At welterweight, fellow undefeated young titleholders Ike Quartey and Felix Trinidad loomed. They were the real tests, the threats to come, and the whispers were starting.

When?

The answer would come, but it would take a little longer than 1998.