An Inductee Experiences the International Boxing Hall of Fame – Part Two

My induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame came about as a consequence of my writing. So allow me to share some thoughts about the written word.

Alan J. Lerner (who created My Fair Lady, Gigi, and other musical classics in tandem with Frederick Loewe) observed, “I write not because it is what I do but because it is what I am; not because it is how I make my living but how I make my life.”

That’s how I feel about writing. I write for history and I write for myself. For history in that I’m creating a record that future generations will read to understand the people, places, and events that I wrote about as I experienced them. And for myself, in that, almost always, I write what I want to write. It has been a long time since I wrote something I wasn’t interested in simply for the money.

Joe Parkhurst (a character in a short story by Paul Gallico entitled “The Melee of the Mages”) summed up sportswriting with the declaration, “All you do is sit down at a typewriter with a lotta paper and just tell what happens to somebody.”

But the craft is more demanding than that. Sportswriting is about sports. But good sportswriting is also about writing.

Jerry Izenberg recently noted, “Too many sportswriters today are nothing more than paparazzi of the written word. A story breaks; they swarm all over it with little or no understanding; and then they’re gone. And you hear all the time, ‘Oh, didn’t he write a great line.’ Well, I don’t write great lines. I’m a writer.”

Asked for more, Izenberg declared, “You have to be a reporter to be a good boxing writer. Yes, you have to be an interpreter and put things in perspective. But facts are at the core of whatever you write.”

As a writer, I sit on the easy side of the ropes. I take notes, not punches. But a good writer – like a good fighter – takes risks. That means standing up to powerful interests and telling truths that the powers that be don’t want spoken. Over the years, I’ve given out praise and I’ve held feet to the fire. I take pride in a comment that Jim Lampley made years ago: “There are two kinds of people in boxing – those who say, ‘Oh, boy; Thomas Hauser is writing an article about me,’ and those who say, ‘Oh, shit; Thomas Hauser is writing an article about me.'”

Prior to beginning my career as a writer, I spent five years as a litigator with a Wall Street law firm called Cravath Swaine & Moore. Since then, I’ve written novels and non-fiction books about subjects as diverse as United States foreign policy, race relations, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and Beethoven. The first boxing writing I ever did was in 1979 for a magazine called Cavalier. It was an article about WBA light heavyweight champion Mike Rossman (whose father’s last name was DiPiano). Rossman (known as “The Jewish Bomber”) used his mother’s maiden name when fighting and wore a star of David on his trunks. I wrote about him through the eyes of his mother. Cavalier liked the piece and commissioned a second article – a formulaic work that quoted four heavyweights on what it felt like to get knocked out.

In 1983, I decided to write a book about sports. I was a casual boxing fan at the time. My favorite sports were baseball, football, and basketball. A writer can’t just walk into Yankee Stadium and talk with the Yankees. But a writer can walk into almost any gym in the country and talk with the fighters who are training there.

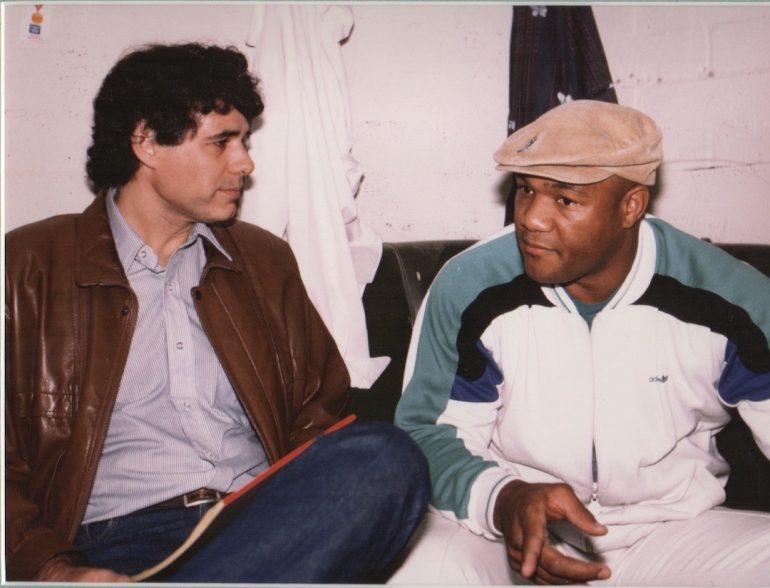

So I wrote a book about the sport and business of boxing titled The Black Lights. Then I put boxing aside to write a murder mystery, a thriller about a plot to manufacture nuclear weapons for sale to third-world countries, and a book about Chernobyl. In 1988, I was approached by Muhammad and Lonnie Ali who asked if I’d be interested in writing what we hoped would become the definitive Ali biography. Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times was published in 1991. After that, I took a hiatus from boxing until 1999 when I began writing for several internet sites.

So I wrote a book about the sport and business of boxing titled The Black Lights. Then I put boxing aside to write a murder mystery, a thriller about a plot to manufacture nuclear weapons for sale to third-world countries, and a book about Chernobyl. In 1988, I was approached by Muhammad and Lonnie Ali who asked if I’d be interested in writing what we hoped would become the definitive Ali biography. Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times was published in 1991. After that, I took a hiatus from boxing until 1999 when I began writing for several internet sites.

When I finished writing The Black Lights, I thought I was an expert on boxing. I wasn’t. I was an informed fan. Writing about the sweet science for various websites taught me how much I didn’t know. And the internet has been an ideal forum for me because I can write as many words as I want to write.

My writing about boxing falls into four categories. First, there’s The Black Lights. Then there’s everything Ali, which includes the big biography, numerous articles (published later in book form under the title Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest), and the text for three Ali coffee-table photo books. I’ve also written two novels that focus on boxing – Mark Twain Remembers and Waiting for Carver Boyd. The novels constitute some of the best writing I’ve done about the sweet science. But to my mind, my most lasting contribution to the sport has been in the fourth category.

For two decades, I’ve chronicled the contemporary boxing scene in articles for various websites and print publications. These articles have covered every aspect of the sport and business of boxing. Initially, internet writers were treated as unloved stepchildren by the powers that be in boxing. Inexorably, the walls came tumbling down. I’m now the first writer whose articles were featured primarily on the internet to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

From time to time, I’m asked for advice on what it takes to be a good boxing writer. I often answer, “Rule number one is, ‘If there’s free food, grab it.’”

But let me give a more serious answer. We’re living in an age when responsible journalism is under siege. Too often, good writing and journalistic sensibilities take a back seat to lesser agendas. I’d like to offer some thoughts on what it takes to be a responsible journalist and good writer:

(1) Challenge every word you put on paper. Lonnie Ali once asked me to review a short piece she’d written about Muhammad. It was well done but one phrase troubled me. Lonnie had written that Muhammad was “one in a million.” But if Muhammad was one in a million, there would have been 350 more people just like him in the United States. “He’s not one in a million,” I told Lonnie. “He’s unique.”

(2) Years ago, I wrote a spy story entitled Hanneman’s War that was set in the mountains of Nepal. I got fifty-five rejection letters before landing a publisher. Rejection letters are rarely helpful to an author. They’re usually limited to, “Thank you for submitting your manuscript. Unfortunately, it’s not suited to our needs.” Other times, an author might be left shaking his head. One day, I got two rejection letters for Hanneman’s War. One of the letters said the book needed more background on Nepalese politics. The other rejection letter said the book needed less background on Nepalese politics. But there was a common thread in that several of the rejecting editors thought the book’s protagonist was unsympathetic and thoroughly dislikable. How could these editors think that, I wondered. Didn’t they understand how much the character I’d created was suffering? No! They couldn’t understand because his suffering was largely in my head. I hadn’t spelled it out clearly on paper. If you want a reader to know something, make sure it’s incorporated in what you write.

Hauser in the dressing room with Manny Pacquiao and Freddie Roach before Pacquiao’s 2010 147-lb. title bout with Joshua Clottey.

(3) Be creative. When John Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 and thousands of journalists descended on Washington DC for the funeral, Jimmy Breslin found a way to separate himself from the pack. He interviewed the man who dug the fallen president’s grave at Arlington Cemetery. As a journalist, I try to come up with ideas and notice things that other people haven’t. As an example; on May 5, 2007, Oscar De La Hoya and Floyd Mayweather fought at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Almost two-thirds of the seats in the sold-out arena carried a price-tag of $2,000 or more. There were 800 requests for media credentials. Five hours before the main event began, two fighters named Ernest Johnson and Hector Beltran fought in an eight-round lightweight bout. The doors to the arena hadn’t opened when they made their way to the ring. I tracked Johnson and Beltran on fight day and chronicled their experiences in an article entitled “First Bout at 3:05 PM.”

(4) Journalism involves building relationships. Being able to pick up the phone and call someone for information and insights is invaluable to a writer.

(5) Set things up in advance. Years ago, I wrote an article entitled “My 81-Year-Old Mother Meets Don King.” The meeting occurred at the final pre-fight press conference for Samuel Peter versus Jameel McCline at Madison Square Garden. I didn’t just show up at the press conference with my mother. I cleared her coming in advance with Alan Hopper (director of public relations for Don King Productions). That meant there was no issue as to whether my mother would be allowed into the press conference. And Hopper arranged for her to meet King. Years later, my mother was in a restaurant on the east side of Manhattan when a loud booming voice proclaimed, “It’s Tom Hauser’s momma!” There was a time when Don remembered everyone and everything.

(6) Just voicing an opinion doesn’t make you a journalist. Back up your opinions with thorough research and facts. And check your facts. All of us make mistakes. In the early 1980s, I wrote a love story titled Ashworth & Palmer that was set in a large Wall Street law firm. One of the scenes occurred in a fictitious industrial suburb that I called Unger and located twenty miles north of Cleveland. After Ashworth & Palmer was published, I got a letter from a reader who told me that he’d enjoyed the book but thought I should know that twenty miles north of Cleveland would place Unger underwater in the middle of Lake Erie.

(7) It’s permissible to excerpt and combine quotes from a single speaker. But don’t change their meaning when you do it.

(8) Respect confidences but don’t hide behind them. And don’t make stuff up. As attorney Judd Burstein once said in excoriating a writer, “Those little voices you hear in your head aren’t sources.”

(9) Edwin Pope (whose writing graced the pages of the Miami Herald for decades) felt a responsibility when he sat down to write. “I held the gun,” Pope noted. “I didn’t want to fire it randomly. I always wanted to be fair, even to people who didn’t deserve it.” When I finish writing an article – particularly an investigative report – I read it through at least once with fairness to the people I’ve criticized foremost in my mind.

(10) Conduct yourself like a professional. I recall sitting in the press section at Barclays Center several years ago. The writer sitting next to me was on his laptop, surfing the internet for porn. There’s a time and place for everything. That was the wrong place at the wrong time.

(11) Use the same standard of care for everything you write. Each article with your name on it will become part of your creative legacy whether it’s written for an obscure website or The New York Times. Also, too many writers today care more about breaking a story than writing well and putting that story in context. I don’t care about being first. I want to be best. Whenever you write, ask yourself, “How will this article read years from now?”

(12) Don’t become a writer for the money. For most writers, the business end of things isn’t very profitable. Your satisfaction as a creative artist will be in writing well and getting published.

Boxing is the best writer’s sport in the world. If you can’t write well about boxing, you can’t write.

This is the second in a four-part series. Go to Part 3.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is [email protected]. His most recent book – Broken Dreams: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.