An Inductee Experiences the International Boxing Hall of Fame – Part Three

Prior to going to Canastota for Induction Weekend, I asked some previous inductees what the experience was like.

“You get a good feeling being there,” Teddy Atlas said. “People come from all over the world for a four-day celebration of boxing. And they respect boxing. They care about boxing. They really do.”

“Most people you meet will be very nice,” Al Bernstein told me. “And the people who run things are incredibly well-organized, so you won’t have to worry about where to be at what time or how to get there.”

“It was overwhelming,” Marc Ratner offered. “I got up to make my speech and turned around. And there were Marvin Hagler, Roberto Duran, and Ray Leonard sitting behind me.”

“It was one of the great feel-good experiences of my life,” Don Elbaum reminisced. “Now, every morning when I get up, I kiss my ring. Don’t ask me why because I don’t know why. I just know that it felt so good getting into the Hall and it still feels good. Every day there’s sunshine in my life because I’m in the one boxing hall of fame that really matters.”

I drove from New York City to Canastota on Thursday, June 9, with my niece (Jessica), her husband (Bayo), and their 16-month-old son (Simon). The Hall of Fame arranges and pays for air transportation for inductees. But by the time I journeyed to the airport, sat in the boarding area, boarded the plane, flew to Syracuse, waited for my luggage, and got to the hotel, it would have taken as long as driving from Manhattan and been less pleasant. The 250-mile drive took four-and-a-half hours. Simon was remarkably well-behaved.

In previous years, inductees had stayed at Day’s Inn, a stone’s throw from the Hall of Fame museum in Canastota. Not everyone was happy with the experience.

“I’ve made two great mistakes in my life,” Jerry Izenberg told me. “One of them was marrying my second wife and the other was staying at Day’s Inn.”

“Day’s Inn isn’t bad if you don’t mind listening to the people in the room next door making love,” Craig Hamilton added.

Canastota is nestled in an attractive rural setting and is similar in many ways to what it was fifty years ago. Most of the major Induction Weekend activities would be held at Turning Stone Resort Casino in nearby Verona. That’s where the inductees, myself included, were lodged.

It was the first time I’d traveled overnight since the pandemic began. We arrived at Turning Stone at 4:15 PM and I checked into my room on the fourth floor. Virtually no one in the hotel was masked, a marked departure from the west side of Manhattan which had been my world for the preceding twenty-seven months. I’d decided before journeying to Canastota to adhere to a risk-reward formula. Having been double-vaccinated and double-boostered, I put my mask aside for most of the next few days and went with the flow.

Traditionally, the Hall of Fame’s induction festivities take place over the second weekend in June. Executive director Ed Brophy is passionate about the Hall, and that passion is reflected in everything he does. More than 150 volunteers support the effort. Seventy-five percent of them live in Canastota. Virtually all of the others come from within a thirty-minute drive. None of the volunteers are paid. They’re uniformly well-informed, well-trained, and exceptionally nice.

There was a buffet dinner for inductees and their guests in the Mohawk Room at Turning Stone on Thursday night. Not all of the inductees were onsite yet. But those who’d arrived were happy to be there.

“This is a party you don’t want to miss,” Roy Jones said.

Miguel Cotto sat quietly at a table with a few family members and friends. Jim Lampley had planned to attend Induction Weekend but was sidelined by COVID. In lieu of coming, he sent a text to Brian Perez (Miguel’s best friend) that read, “There were so many things that established Miguel’s unique class and dignity. And I will always remember with gut-wrenching sadness that he was victimized in the ring by a blatant criminal assault, that it robbed him of not just a title but of the kind of trust in the sport and its surrounding institutions that fighters need to commit to dangerous competition. Only a twenty-year prison sentence for assault with a deadly weapon could have repaid that debt. Only someone with the innate dignity and inner strength of Miguel Cotto could have endured that the way he did. That, forever, to me,” Lampley concluded, “is the legacy of Miguel Cotto.”

Friday began with a buffet breakfast in Parlour, a lounge set aside each morning for inductees, family members, and friends. Julian Jackson (a 2019 inductee) was there with his high school sweetheart, who has been his wife for decades.

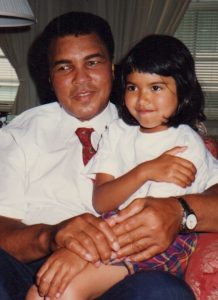

Jessica Hauser and Muhammad Ali

At sixteen months, Simon (my great-nephew) doesn’t talk yet except for the occasional “momma.” But he was toddling around the room, high-fiving some of the greatest fighters of our time. It brought back memories for me of Jessica (Simon’s mother) sitting on Muhammad Ali’s lap and singing the Barney song with him when she was six years old.

Shane Mosley, gracious as always, was in a reflective mood.

“This is bittersweet,” Shane told me. “When I started boxing, I dreamed about being in the Hall of Fame someday. This is the best validation I could have, but it means that a part of my life I loved is over.”

Late in the morning, most of the inductees boarded a bus for a short ride to Theodore’s (a restaurant in Canastota), and I found myself sitting next to Bernard Hopkins.

Promoters and managers have their money to count when their careers are at an end. Hopkins (unlike many fighters) has his money (a lot of it) and a legacy of historic proportions.

“I felt complete when I retired from boxing,” Bernard told me. “But I’m grateful to be here this weekend. You can lose your money, but history never goes broke.”

Hopkins burned a lot of bridges over the years. But he has rebuilt many of them.

“Roy Jones in 1993 was the best fighter I ever fought,” Bernard said, looking around the bus. “He was the Michael Jordan of boxing back then and I didn’t have the boxing IQ at that time to know how to deal with him.”

Marvelous Marvin Hagler once said of Induction Weekend in Canastota, “You run into guys you knocked out or you lost to, and you’re able to shake hands and catch up. Fighters are able to laugh and be friendly with one another after a guy’s beaten the shit out of you.”

That sentiment was on display during lunch at Theodore’s. Other fighters in addition to the inductees were sprinkled around the room. Terence Crawford, Shawn Porter, Marlon Starling, Antonio Tarver, Iran Barkley, Junior Jones. There was genuine camaraderie and warmth. Old adversaries embraced. No one tried to one-up anyone else.

Hauser, Simon and Roy Jones Jr.

Some of the inductees in the room had fought each other in the past. Roy Jones fought James Toney and Bernard Hopkins. Christy Martin battled Laila Ali. In some ways, the scene reminded me of a dysfunctional family reunion with everyone on their best behavior.

After lunch, we got back on the bus and rode to the Hall of Fame museum.

Fifteen years ago, Bill Simmons wrote, “American kids don’t grow up hoping to become the next Ali or Sugar Ray anymore. They’re hoping to be the next LeBron, Griffey, Brady or Tiger. The thought of getting smacked in the head for twenty years, soaked by the Don Kings of the world, and then ending up with slurred speech and a constant tremor doesn’t sound too enticing.”

But boxing is alive and well in Canastota. The International Boxing Hall of Fame is limited in physical form to a small museum and outdoor event pavilion. But in the imagination, it’s as large and grand as the storied history of boxing.

I’d never been to the Hall of Fame before. The first thing I did on entering the museum was look for my plaque. Then I surveyed the robes, trunks, and gloves worn by legendary fighters, fight tickets, fight programs, and more.

From Ed Brophy’s point of view, the most important artifact in the museum is the ring that was used at various incarnations of Madison Square Garden from 1922 to 2007.

“Think of what happened in that ring,” Brophy told me with awe in his voice. “That’s where Muhammad Ali fought Joe Frazier and Joe Louis fought Rocky Marciano. Sugar Ray Robinson won his first world championship in that ring. So many great fighters of the past hundred years fought there.”

But the real attraction for me at the museum were the fans. Dedicated, well-informed, passionate fans.

Fans at the IBHOF induction weekend. Photo by Alex Menendez/Getty Images

Eyes light up when sports fans in a casual setting come upon a great champion. “Omigod! That’s Michael Spinks” was heard decades ago when Spinks was out in public after dethroning Larry Holmes.

The years pass. The fighter grows older. Maybe on occasion he hears, “I think that’s Michael Spinks.”

At Canastota, I heard, “Omigod! That’s Michael Spinks.”

And then there were the autograph seekers.

Eight decades ago, Paul Gallico wrote, “The average man is not requested for his autograph, except on a check, more than once or twice in his life. No one who has not been through the mill has even the faintest notion of how wearing on the nerves and exasperating the constant and unremitting request for autographs becomes.”

Certainly, that was true for Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey (two of Gallico’s favorite subjects). But for most of us, being asked for an autograph is an ego boost.

Many of the fans who visit Canastota are collectors.

“You’ll sign more autographs in four days than you have in your entire life,” Al Bernstein told me. “The Hall will have all sorts of things for you to sign, and you’ll meet hundreds of people who will want you to sign everything else. The first time you’re asked to sign your name and put ‘HOF’ with your year under it, you’ll get a little thrill.”

When I was young, I was an avid collector. I still have my autograph collection and add to it from time to time. I remember how much it meant to me when someone signed something for me. So in Canastota, I signed and signed.

I signed books, induction programs, photos, gloves, index cards, and more. Most people asking for signatures had a Sharpie in hand.

Signing autographs in Canastota reminded me of an experience I had with Muhammad Ali (who probably signed more autographs than anyone else since the beginning of time).

In 1996, Easton Press published 3,500 copies of a leather-bound edition of Muhammad Ali: His Life And Times. Pursuant to contract, Ali and I signed 3,500 signature pages for insertion in the book. I was paid three dollars per signature; Muhammad, considerably more.

“This is fantastic,” I told myself. “If I do ten signatures a minute, that’s 600 signatures an hour. Divide 3,500 by 600. Wow! I’ll get $10,500 for six hours work.”

Except when I started signing, I couldn’t sign more than a hundred-or-so pages at a time. “Any more than that,” I confided to Muhammad, “and I can’t connect the letters properly. Something starts misfiring in my brain.”

“Now you know,” Ali told me, referring to his own physical condition. “It wasn’t the punches. It was the autographs.”

There was another buffet dinner on Friday night for inductees, family members, and friends. Then I went to the Turning Stone Event Center to check out the ShoBox fights. Olympic super-heavyweight gold medalist Bakhodir Jalolov was scheduled to face Jack Mulowayi in the main event. But the Golden State Warriors were playing the Boston Celtics in Game 4 of the NBA Championship Finals. I was tired and wanted to see the game, so I left the fights early.

As I walked back to my room, it was clear that Induction Weekend was a magnet for the boxing community. I chatted with Paulie Malignaggi (who I’ve known since he was twenty years old) and Freddie Roach (whose most endearing quality is that, as his fame and fortune grew, he didn’t change). Kevin McBride (the only man in the house to have beaten Mike Tyson) was wandering about.

I signed a dozen-or-so autographs on my way to the elevators; then went upstairs and watched the game. Stephen Curry erupted for 43 points as the Warriors evened the series at two games apiece. Curry, it occurred to me, plays with the kind of magic that Roy Jones once exuded in the ring.

This is the third in a four-part series. Go to Part 4.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is [email protected]. His most recent book – Broken Dreams: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.