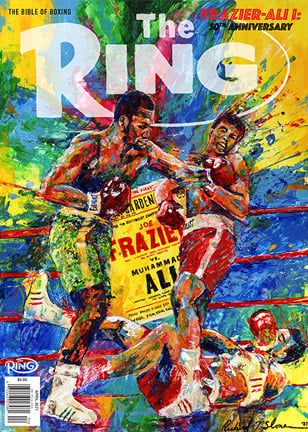

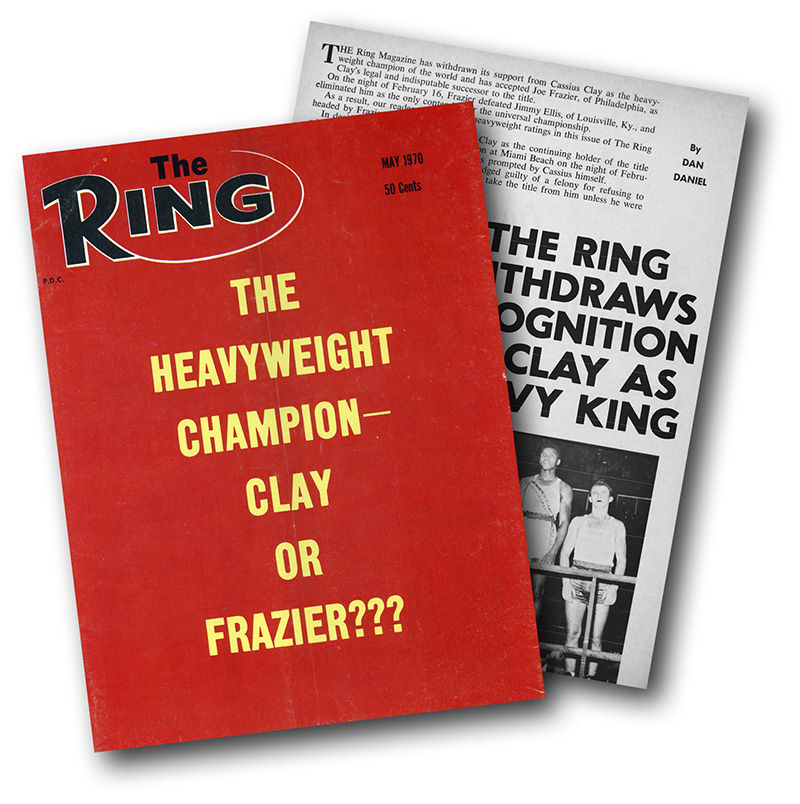

THE RING WITHDRAWS RECOGNITION OF CLAY AS HEAVY KING

This feature originally appeared in the May 1970 issue of The Ring Magazine.

Editor’s note: The following reprinted article contains language, including referring to Muhammad Ali as Cassius Clay years after he legally changed his name, that could be construed as offensive. In the interest of historical integrity, we did not remove the author’s original words from the story. We present this archival material as it was originally published (including the title of the article), in part, to document the issues and social context of the times, which include the attitudes and opinions of the people who covered the fights and events.

The Ring Magazine has withdrawn its support from Cassius Clay as the heavyweight champion of the world and has accepted Joe Frazier, of Philadelphia, as Clay’s legal and indisputable successor to the title.

On the night of February 16, Frazier defeated Jimmy Ellis, of Louisville, Ky., and eliminated him as the only contender for the universal championship.

As a result, our readers will find the heavyweight ratings in this issue of The Ring headed by Frazier, all alone.

In deciding to withdraw its backing of Clay as the continuing holder of the title which he won by knocking out Sonny Liston at Miami Beach on the night of February 25, 1964, in seven rounds, The Ring was prompted by Cassius himself.

In deciding to withdraw its backing of Clay as the continuing holder of the title which he won by knocking out Sonny Liston at Miami Beach on the night of February 25, 1964, in seven rounds, The Ring was prompted by Cassius himself.

Since 1968, with Clay inactive and adjudged guilty of a felony for refusing to accept the draft call, The Ring had refused to take the title from him unless he were found guilty of the felony by the Supreme Court of the United States and forced to enter a Federal penitentiary for a period of five years with the additional punishment of a fine of $10,000. As ruled by the Federal courts, these judgements were not eliminated by the Supreme Court’s first review of the Clay case.

That review asked the Federal courts to ignore, in consideration of the felony charge, any evidence which the government might have obtained through wiretapping and bugging, and any other material picked up by clandestine methods.

Month after month, against the dissent of a considerable percentage of its readership all over the world, The Ring persisted in its stand that Cassius Clay was entitled to his day in court. The Ring held that he could not be deprived of the world championship unless the Supreme Court found him guilty of a felony, or Cassius Clay, of his free will and uncoerced determination, gave up the world championship and announced his retirement from boxing.

Month after month, Clay held to his defense that, as a lay preacher of the Black Muslim church, and as a conscientious objector, he could not be denied exemption from Selective Service.

In supporting Clay’s right to hold the world title, The Ring did not back up his claims as a preacher and conscientious objector. But it did insist and persist that Cassius could not be shorn of his championship unless his defense was utterly controverted and his points were denied by the courts.

Or, if supported by the courts, he were to lose his title in the ring.

Last summer, Clay, making talks all over the country, said that he would fight no more.

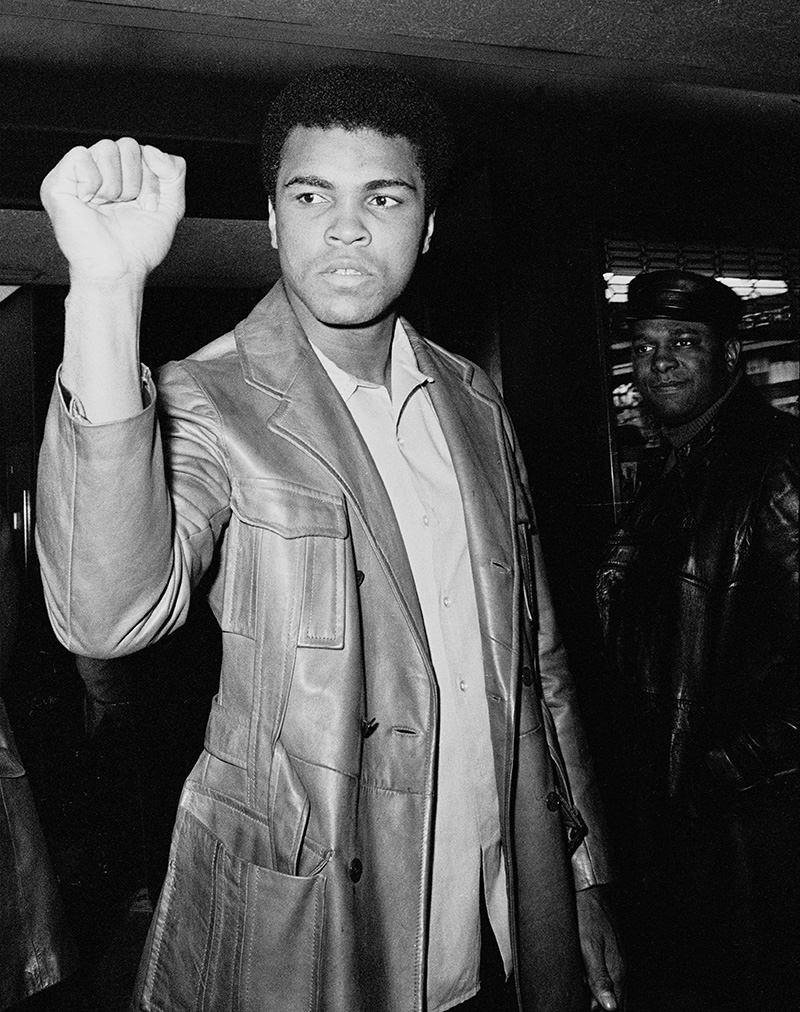

Ali on December 15, 1970 in New York, New York. (Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images)

He had gotten into difficulties with Elijah Muhammad, the Black Muslim ruler. Cassius had been suspended by the Muslims for one year and he appeared to be upset thereover.

Disturbed by its standing up for the man who kept telling the public that he would fight no more in the arena, The Ring got in touch with him. The results of a telephone conversation with him at his home in Chicago were inconclusive. He said that he had not made up his mind. This appeared to kill his retirement statements.

Last December, Clay returned to his retirement stand. Later, he appeared in a Broadway stage production in which his limited skills were assessed as being superior to his vehicle. The play made a fast exit.

In February 1970, Cassius Clay’s expressed determination not to appear in the ring again as a professional became more emphatic than ever. He said that he would present to the winner of the Frazier-Ellis fight the world championship belt which had been awarded to him by The Ring Magazine in 1964.

A few days before the Frazier-Ellis contest, Eddie Dooley, chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission, ruled that Clay would not be permitted to make the presentation in the Madison Square Garden ring. Cassius thereupon announced that he would ship the belt to his Louisville alma mater, Central High School.

Nat Fleischer, editor and publisher of The Ring, who had become friendly with Clay at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, where Cassius won the light heavyweight title, called a staff conference and asked for a determination of the Clay case.

It was the strong sentiment of the staff that Clay had given up the world championship of his free will and that The Ring had been released from its commitments on his behalf.

The Ring decision was made without a dissenting voice. It also was voted that the winner of the Frazier-Ellis fight could be recognized by this magazine as the new heavyweight champion of the world.

If, as many skeptics predict, Clay changes his mind about quitting the ring and the lush paydays which would become available to him if he were cleared by the Supreme Court, Cassius would have to appear as the challenger, and emphatically not as the champion.

His position would be similar to the one in which Jim Jeffries found himself on July 4, 1910, at Reno, Nev., where he challenged Jack Johnson, the titleholder, and was knocked out in 15 rounds.

Jeffries had retired in 1905 and announced that he was handing the title to the winner of a bout between Marvin Hart and Jack Root.

Hart beat Root, Tommy Burns beat Hart, and Johnson stopped Burns in 14 rounds on December 26, 1908, at Sydney, Australia.

The lucre lure got the better of Jeffries, and he went after Johnson, who was far superior to the once mighty Boilermaker.

Johnson was beaten by Jess Willard, and then Jack Dempsey knocked out Big Jess.

Retiring unbeaten, Black Muslim Clay achieves a fistic distinction which hitherto had been gained by only two other heavyweight champions, Gene Tunney, in July 1928, after he had knocked out Tom Heeney, and Rocky Marciano, in April 1956, following his nine-round victory over Archie Moore.

Ali in a publicity photo for the Fight of the Century. (Photo by John Shearer/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

If the Supreme Court finds the case against Clay indefensible by him and ships him off to jail, Cassius will find himself in a sorry plight shared by no other world heavyweight champion.

No other heavyweight champion has resisted an Army call to duty.

No other boxer ever placed himself on record as a conscientious objector.

No other professional boxer ever before asked the public to accept him as a preacher for a religious sect while he yet was competing.

No other professional fighter, still seeking to defend a world title, refused national service in a time of battle.

Tunney came out of the Marines. Max Schmeling doubtless had no option, but he did serve when called by Hitler’s army.

Joe Louis enlisted and fought several times for service relief funds.

The Ring wishes to take the opportunity to thank those of its readers who dissented pleasantly from its policy in backing Cassius as the champion, against claims of Ellis, who won the WBA elimination tournament, and Frazier, whose title claims were supported by six states and some foreign countries. Dissenting readers never denied The Ring’s rights to support Clay.

The position now adopted by The Ring will be acclaimed by the British Board of Boxing Control and many other governing bodies.

Elimination of Clay will clear up a heavyweight muddle which hurt all boxing throughout the world.

The Ring admitted the existence of this injury, but, nevertheless, fought for the right.

The Ring offers its congratulations to Frazier as the new champion, and its condolences to Ellis, who was a gentleman all the way.

Their campaigns toward the confrontation in New York were happily and pleasantly devoid of personalities, and that scurrilous vituperation which sometimes has entered into such situations. Boxing has grown up.