JOE FRAZIER’S FAMILY ALSO ENDURED ABUSE IN THE BUILDUP TO THE ALI FIGHT, BUT ULTIMATELY THEY SHARED IN HIS VINDICATION

Regardless of what the reigning heavyweight champion of the world did, his kids had to go to school the next day. Joe Frazier would not have wanted it any other way, despite fighting Muhammad Ali on Monday night, March 8, 1971, at the hub of the universe, a raised illuminated canvas in the middle of Madison Square Garden.

Weatta and Marvis Frazier, two of Joe’s children, and Mark and Rodney Frazier, the nephews of “Smokin’ Joe,” were young kids when Frazier took on “The Greatest” in a clash of unbeaten heavyweights against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and racial and political unrest.

The world was talking about “The Fight.”

But to four wide-eyed children, they had no full grasp of what was happening around them. Weatta and Marvis knew TV trucks were constantly pulling up to their home, and talk on the news about Frazier’s preparation for the fight was persistent.

It’s why the quartet has a greater appreciation for what Frazier did that night, and, more importantly, how he carried himself before and in the aftermath.

Weatta, Marvis, Rodney and Mark’s classmates reminded them daily how their “daddy” and their “Uncle Billy” (a nickname Joe inherited from his father, Rubin, who used to call him “Billy Boy” in his youth) was going to get obliterated by Ali.

Joe himself knew the talk. It fueled his anger toward Ali. But his family lived it.

It was business as usual for Frazier ahead of his biggest-ever fight. (Photo By John Shearer/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

“My father was very protective of all of us, so protective that he actually had Lee Grant Pressley, one of his bodyguards, take us to school every day,” recalled Weatta Frazier-Collins, the third of Frazier’s children, who was 7 at the time. “My father made sure we were all grounded. We knew something big was happening, but to my father, it was like he was a construction worker going to work every day, 9-to-5 in his hard hat, and then come home.

“I’ll tell you, it’s difficult for me to watch that fight even today. I know my father fought a major fight and I can’t watch those fights, because those fights are still very, very painful for me to see. I remember, looking back, how much of a blessing (Frazier’s trainer and manager) Yank Durham was in my father’s career. He made sure my father was safe. People also forget my father, this little man, barely 5-foot-10, beat a giant, Muhammad Ali.

“My father always had diabetes, and he could barely see out of one eye. People forget that. It’s why he got hit so often. When his sugar levels were off, he had problems. But he had one simple message, and he always said the same thing during that time going into the Ali fight: ‘Get the job done.’ When Ali hit my dad, it was like he was hitting me.

“I still feel that pain.”

Rodney Frazier, the son of Joe’s sister Rebecca, had a sense of what was happening. He was 13 at the time and watched the fight with his maternal grandmother, Dolly, on a closed-circuit broadcast in a small, empty arena in Charleston, South Carolina, tickets paid for by Joe.

Dolly was a very stoic person who sat and watched. She saw her son make history in beating Ali for the first time without blinking an eye.

“I remember the turmoil my family went through during that time, and we couldn’t win,” Rodney, 62, said. “The Blacks were angry at us, and the Whites hated us. I remember sitting with my grandmother and you wouldn’t know if her son won or lost. She showed no emotion. It’s how my Uncle Billy viewed fighting. You go to work and you do your job.

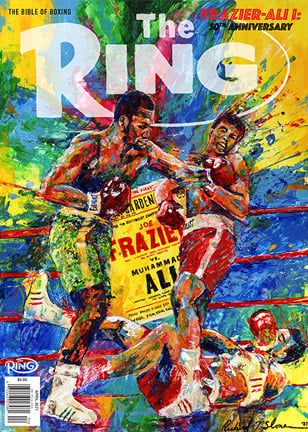

Frazier’s devastating left hook produced arguably the most iconic knockdown in boxing history.

“My Uncle Billy’s victory was a great victory for the family. He took care of all of us. My father was never in my life. Joe was like my father. We came from the rural South and we had so few heroes then, other than Martin Luther King – and my uncle.

“I remember after that fight asking my uncle one day if he was tired fighting Ali that first time. He said he was tired, but he told me, ‘If that motherfucker was going to get up off that stool in the 15th round, I was going to get off the stool. I asked God to help me, but not to help me win. I asked God to help me kill this motherfucker. That man was the devil. I did every good deed that I could for Ali to fight again; I gave him money for his family. The cameras came on and I was a gorilla and an Uncle Tom. He made me so angry that I wanted to kill him.’

“My uncle never liked playing games. Ali played games. I remember him saying all of that stuff very clearly like it happened yesterday. My uncle never had doubts he was going to beat Ali. He went to work and he was partially blind in his left eye, and he had high blood pressure. He was a Type 1 diabetic. He overcame all of that to become world heavyweight champion. Think about that.”

The sporting feud continued with daughters Jacqui Frazier-Lyde (left) and Laila Ali. (Photo by SCOTT NELSON/AFP via Getty Images)

Mark Frazier, the son of Joe’s brother Tommy, was 12 years old when Frazier-Ali I took place. Mark was living in Harlem, New York, at the time, and he endured endless teasing as a child when the fight was building. Before moving to Philadelphia in 1959, Joe lived for a period of time with Tommy and slept in the same bed as Mark.

In 1970, Ali appeared at Mark’s junior high school. Ali called Mark up on stage.

“It was a great moment, because I got to be called on stage with Muhammad Ali, and he was a very gracious guy. He kept asking me if I was a Frazier, and [said] I was ‘too pretty to be a Frazier,’” Mark recalled. “That was over 50 years ago and I lived long enough to see that on YouTube. But I remember getting a lot of grief from the kids in school about that fight.

“That night was really cold. My Uncle Billy used to come up and see us in Harlem, but Uncle Billy always had a smooth, calm demeanor. Nothing seemed to phase him. He would laugh and joke about the fight, but he never showed any nervousness. It was always about getting the job done. That’s the way he looked at life: If you prepare right, you’re going to win. He never had any doubt he would [beat] Muhammad Ali.”

Mark and his sister weren’t allowed to go to the fight, because they were too young, but they kept getting updates as to how their uncle was doing. When the result arrived, their Harlem street exploded like New Year’s Eve.

“People also forget my father, this little man, barely 5-foot-10, beat a giant, Muhammad Ali.”

– Weatta Frazier-Collins

“It’s the first time in my life I couldn’t wait to go to school and remind everyone that bad-mouthed my uncle and let them know that my Uncle Billy was the heavyweight king of the world,” Mark recalled. “A month later, we went down to Philly to see him, and you wouldn’t know he was the heavyweight champion of the world. He was still the same.”

Marvis Frazier was 10 when his father fought Ali at Madison Square Garden. Joe wouldn’t permit his son to go to the fight, fearing something might happen to Marvis.

Marvis Frazier (right) and Rev. Blane Newberry from Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church beside the statue of Joe Frazier unveiled in 2015. (Photo by David Swanson/Staff Photographer/Philly.com)

“I remember every day, he would get up for a morning run and really treat it like it was any other fight,” Marvis said. “My dad didn’t talk too much about the fight. There were a lot of people around the house and I didn’t even get a chance to watch the fight live. We heard that my daddy won the fight. I remember having to go to school the next day.

“My dad wouldn’t let us take a day off from school. My dad was strict like that. That Tuesday, I was right there in class and I remember all of the kids coming up to me congratulating me about my dad winning. I found out a lot of people cheered for my dad, too.

“I remember seeing all of these TV cameras and all of these TV trucks around our house the next day. I didn’t really know what was going on then, but I knew my dad won that fight. It’s a night that changed our family.”

Tamyra Frazier, Marvis’ 36-year-old daughter and Joe’s granddaughter, has a graduate degree and is working on her PhD. Jacqui Frazier-Lyde, Joe’s oldest daughter, is a Philadelphia municipal court judge. Numerous Fraziers have gone on to get college degrees, all coming from a man who worked the fields in South Carolina.

“I watched that fight many times, and I think back that whatever drive my grandfather had, I have,” Tamyra said. “You know, a lot of people my age think Ali won that first fight. I’m a mom now with two kids (8 and 9, a boy and a girl). They’re just starting to learn about their great-grandfather. Sometimes, society picks our heroes and our winners, and forget that there are a lot more Joe Fraziers in the world – who don’t get the recognition that they deserve – than Muhammad Alis.

“My grandfather is a part of history. You can’t undo history. No matter who or what people may think, Joe Frazier was the first one to beat Muhammad Ali. That will always be a part of my family.”

Joseph Santoliquito is an award-winning sportswriter who has been working for Ring Magazine/RingTV.com since October 1997 and is the president of the Boxing Writers Association of America.

A collection of past articles from The Ring posted shortly after Joe Frazier’s death in 2011:

THE RING’s tribute to Joe Frazier, Part 1