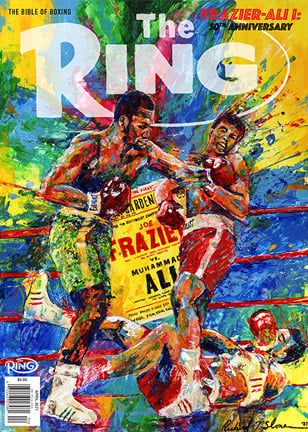

MORE THAN JUST TWO MEN VYING FOR THE HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP, THE FIRST ALI-FRAZIER FIGHT WAS AN AMERICAN CULTURE CLASH

The first fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier – the March 8, 1971, Fight of the Century – would’ve been a huge event even if it were viewed strictly from a sporting perspective.

Ali, returning from 3½ years in exile, and Frazier both were undefeated and had legitimate claims on the heavyweight championship at a time when it was still the most important prize in sports. It might’ve been the biggest fight since the great Joe Louis was at his peak in the 1930s and ’40s.

But that was only part of the story, arguably an incidental part. Ali-Frazier I took place at a time of upheaval in the United States. African Americans were fighting for their rights and the war in Vietnam raged, dividing the country into Black vs. White and anti-war protesters vs. those who supported it.

The fighters took the political divide into the ring with them at Madison Square Garden in New York – Ali on one side of the divide, an unwitting Frazier on the other – in what became an epic battle of competing ideologies.

Journalist Bryant Gumbel, interviewed for the 2000 documentary Ali-Frazier I: One Nation … Divisible, captured the essence of the event.

“It was the greatest sports event of the 20th century,” he said. “Two undefeated champions against a backdrop unique in history.”

***

To understand the significance of the fight, we must go back a few years before it took place.

Ali entered the American consciousness in 1960, when – as Cassius Clay – he won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the Rome Olympics. He turned pro later that year and quickly developed a reputation as both an unusual fighter and character. He had the biggest personality in American sports history, his only rival being Babe Ruth.

In 1964, heavyweight champion Sonny Liston was ready to fight the motor-mouthed upstart, the “Louisville Lip,” a nickname that preceded the moniker “The Greatest.” Few gave Clay a chance to beat the imposing titleholder, but his antics in the lead-up to the fight – outbursts that were both bizarre and amusing – generated fascination.

And, in a great upset, he won the fight, forcing an overmatched Liston to quit after six rounds. Clay hadn’t exactly become a hero, but he certainly “shook up the world.”

Then everything changed.

The month after the fight, Ali, a new member of the separatist Nation of Islam, announced that he was now a Muslim and had changed his name to Muhammad Ali. He was no longer a zany but harmless boxer. He was an unapologetic militant who advocated for separation of the races.

Three years later, on April 28, 1967, he became a symbol of the growing anti-war movement when he refused induction into the U.S. Army on religious grounds. He lost his championship, was banned from the sport, faced the possibility of prison time and had earned the enmity of millions.

The White establishment suddenly reviled him. Most African Americans and liberal Whites – many of them “hippies” who saw evil in the foreign war – embraced him.

“The country was just split completely,” Jerry Izenberg, who covered many of the events leading up to the fight, told The Ring recently. “Part of it was Ali’s comment about not being mad at the Vietcong. That was a major factor, because everyone had an opinion on it.

“Then it just built to a crescendo. It became very emotional.”

Ali’s exile was difficult for him. The boxing world had cut off his livelihood, forcing him to charge for interviews – which he had never done – and speak on college campuses to make ends meet. Things got so bad at one point that he agreed to spar with heavyweight contender Joe Bugner for $1,000 and tried to sell him a primitive portable phone he had somehow acquired for another $1,200, according to the book Bouts of Mania by Richard Hoffer.

“Joe,” he said, “it’s just what you need.” Bugner didn’t buy.

***

Enter Joe Frazier.

“Smokin’ Joe,” whose nickname perfectly described his boxing style, ascended the heavyweight hierarchy while Ali sat idly. The son of poor sharecroppers from South Carolina but a resident of Philadelphia since age 15, Frazier had followed in Ali’s footsteps by winning his own gold medal in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics – in the heavyweight division – even though he fought with a broken thumb.

Frazier had to wait before he could turn pro because of the injury, but he finally made his debut in August 1965. He reeled off one knockout after another – relying heavily on what would become an iconic left hook – to build a reputation as a legitimate challenger to the heavyweight championship, which was vacant as a result of Ali’s actions.

To fill the void, the World Boxing Association organized a tournament of contenders. Frazier was initially among the eight participants, but he pulled out to face the hulking Buster Mathis for the New York State Athletic Commission’s version of the heavyweight title on March 4, 1968, shortly before the tournament final.

Frazier knocked out Mathis in the 11th round to win the New York title and run his record to 20-0 (18 KOs). Then, less than two years later, he did the same to tournament winner Jimmy Ellis in four rounds to gain further recognition as heavyweight champion and take another step closer to meeting the man who would become his greatest rival, one whose name seemed to be on everyone’s tongue.

“[Frazier] had a lot of animosity because he had become great, well-known, and everyone kept saying, ‘But you haven’t fought Muhammad Ali,’” George Foreman said.

Ali was still struggling financially when the public began to clamor for a showdown with Frazier to determine the genuine heavyweight champ. And, of course, Ali desperately wanted to make the fight.

Who was among those he went to in hopes of regaining a license? Frazier himself.

“He called [me and] said, ‘Hey man, I want my license. What can we do?’ I said, ‘I’ll see what I can do to help you get your license,’” Frazier said in the documentary.

Frazier did more than that. Yes, he pulled whatever strings he could to get Ali back into the ring, although it’s not clear what role, if any, that played in Ali’s return. He also helped Ali on his bottom line on more than one occasion.

Butch Lewis, a member of Frazier’s team, told the story of the time he and Frazier pulled up in his limo in front of a hotel in New York at which Ali was staying. Bundini Brown, Ali’s sidekick, saw them and approached. He said Ali was having problems paying the hotel bill. Ali got into the car, they drove off and, as Frazier put it, “I put some love into his hand, some money.”

READ: Bundini — Don’t believe the hype (The Ring, Oct. 2020)

Ali then got out of the car and, like he was given a cue from a director, he began to bellow in the street. “All right, Frazier! Out of the car, now! I want you now! Joe Frazier got my championship! I want to fight Joe Frazier!”

“And Joe’s going, ‘What’s wrong with this guy?’” Lewis said.

Frazier would ask that question many more times going forward.

***

Ali was granted a license in August 1970 by something called the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission, which reportedly was set up specifically for the purpose of having Ali fight there on October 26 while his battle against the United States government was under appeal.

His first opponent was capable contender Jerry Quarry, who took a beating from the much-quicker Ali before the fight was stopped after three rounds because of a cut. Six weeks later, Ali stopped Oscar Bonavena in the 15th round at Madison Square Garden in New York, which had been forced by a judge to reinstate Ali.

Ali thus became the top contender for Frazier’s title. And the wheels that would lead to the showdown began to turn.

Madison Square Garden and the Astrodome in Houston both offered each boxer $1.25 million to stage the fight. But Herbert Muhammad, who handled Ali, and Yank Durham, Frazier’s trainer and manager, knew they could get more and turned to high-powered Hollywood agent Jerry Perenchio.

Some were disdainful of how the fight was made. (Photo By John Shearer/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Perenchio agreed to pay each fighter a record $2.5 million; he got Jack Kent Cooke, the owner of the Lakers, Kings and The Forum in Los Angeles, to provide $4.5 million in financial backing and received the rest from Madison Square Garden, which would charge an unheard-of $150 for ringside seats.

“I never promoted a fight before,” Perenchio said. “It sounded like a hell of an idea. And I thought it transcended boxing because it had to do with the Vietnam War, religion, being Black in America, all of that.

“… I had just one problem: I didn’t have $5 million. And the 77th man I talked to was Jack Kent Cooke.”

The fight was on. So was the name-calling.

Ali took every chance he had to belittle Frazier – at press conferences, on television, at any and all public events. The crudest remarks focused on his appearance and intelligence. “His nose is flat. He’s ugly. He can’t talk,” said Ali, who repeated similar insults throughout the buildup to the fight.

That was nothing compared with his most cutting comments, which questioned Frazier’s loyalty to his own people. Ali called his opponent “Uncle Tom.”

Frazier had, in fact, come to represent those who were angry at Ali – the aforementioned White establishment – but that wasn’t his choice. He wasn’t a political creature, as Ali was. He was a boxer with a wife and kids. His concern was putting food on the table, not changing the world. And Ali evidently resented him for that.

Joe’s son Marvis (and presumably his siblings) suffered as a result of Ali’s words. He was only 10 at the time of the fight.

“I would get in all kinds of trouble in school,” he said. “The majority of kids said, ‘Ali is going to whip your dad. Your dad can’t fight.’ I said, ‘Why are you saying that?’ ‘Cause he’s a Tom.’ ‘What? My dad’s no Tom.’ In the Black community, those are harsh words.

Ali was getting under Frazier’s skin long before the opening bell. (Photo by John Shearer/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

“… I believe what hurt my dad is he gave heart and soul to help another brother. And that brother comes and then, like a knife, cuts him.”

Frazier was hurt. And he never understood the logic of Ali’s stream of insults. Ali would later say that he was only trying to sell the fight, which one could argue makes no sense. Every venue was sold-out or nearly so. And they were both guaranteed $2.5 million. That was set in stone.

Frazier got under Ali’s skin at least once, calling him Cassius Clay on national television, but that was nothing compared to the abuse he received.

“Why is this guy doing this?” Frazier said years later. “Why does he have to say these things about me? I’m an Uncle Tom, I’m the White man’s champion. That wasn’t what it’s all about. It’s about being champion of the world, representing everybody.”

Frazier wasn’t a political creature, as Ali was. He was a boxer with a wife and kids. His concern was putting food on the table, not changing the world.

Izenberg, who wrote about the fight in his book Once There Were Giants: The Golden Age of Heavyweight Boxing, knows why Ali said those things. He was being Ali. “He was just running his mouth,” Izenberg said. “He never knew when to stop.”

Frazier never forgot the insults, which he endured before all three of his fights with Ali. They reportedly became friendly many years later, but Frazier held a grudge.

I interviewed him about 30 years after the first fight for an article in the Los Angeles Daily News. Ali’s declining health at that time – primarily his Parkinson’s disease, which was slowly killing him – came up. Frazier, who had seemed distracted, raised his head and looked me straight in the eyes.

“How do you think he got that way? It was me,” he said, as if he took pride in damaging his rival. That’s how hurt he was.

***

The confluence of sport, Ali’s personality and politics seemed to have whipped everyone into a frenzy by the time fight night arrived.

That included many celebrities, who flocked to an event at which it was as important to be seen as it was to see. Actor Burt Lancaster, a friend of Perenchio’s, was on the broadcast team. A James Taylor concert was scheduled to take place at MSG that night, but the singer was paid off with 15 pairs of tickets and a new date. And Frank Sinatra was hired by Life magazine to be a ringside photographer.

The Madison Square Garden schedule didn’t include ticket prices, because it sold out so quickly. One Garden executive said, “We could’ve sold out 10 Madison Square Gardens.” And no seats could be found at most closed-circuit outlets, which charged as much as $30 for a ticket.

The Madison Square Garden schedule didn’t include ticket prices, because it sold out so quickly. One Garden executive said, “We could’ve sold out 10 Madison Square Gardens.” And no seats could be found at most closed-circuit outlets, which charged as much as $30 for a ticket.

More than 2,000 journalists from around the world submitted requests for 600 credentials, making it clear that Ali-Frazier I was an international phenomenon.

And 300 million people would have the opportunity to watch the fight on TV or in theaters – two million in the United States and Canada, and 298 million in the rest of the world. That was more than 8 percent of the entire population on Earth at the time.

For Frazier, the fight was an opportunity to prove once and for all that he was the best heavyweight in the world and avenge Ali’s cruel taunts. He seethed.

For Ali, it was a chance to regain the title he and many others believed was unjustly stolen from him as a result of his political stance. Just as important, he thought it might be his final payday. The Supreme Court of the United States wouldn’t rule on his case until June. He thought he was going to prison, although he would be vindicated in the end.

For the fans, even those at odds with each other over their ideologies, it was an opportunity to see two of the greatest heavyweights who ever lived do battle in a highly charged environment.

There has been nothing like it before or since.