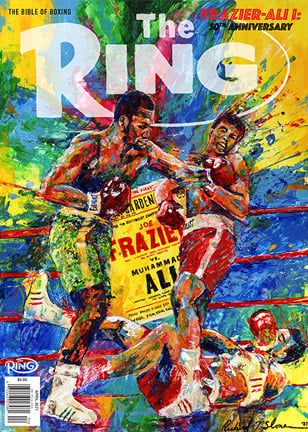

AFTER YEARS OF BITTERNESS AND LINGERING RESENTMENT, ALI AND FRAZIER FINALLY AGREED THAT IT WAS TIME TO MAKE PEACE

These are the most widely recognized lords of conflict, forever at odds with one another in life, legend, lore and literature: Hatfields vs. McCoys, Earps vs. Clantons, Luke Skywalker vs. Darth Vader, Montagues vs. Capulets, Tupac vs. Biggie. In some cases, the friction never rose beyond the threshold of fierce rivalry borne of grudging mutual respect; in others, the animosity was so deep-rooted it crossed over into the ugliness of open hatred.

In sports and specifically boxing, the foremost example of a battle that extended beyond the competitive arena is the justly celebrated three-act passion play involving heavyweight icons Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, whose pride and determination were such that they brought one another to the brink of physical and maybe even psychological ruin. But what transpired inside the ropes, the blood spilled and the lumps raised, only tells part of the story. It was the unnecessarily cruel war of words that was waged over decades between two former friends turned bitter enemies, neither of whom was inclined to yield an inch, that by turns elevated an already remarkable feud into one for the ages. Any number of would-be arbitrators attempted to bridge the chasm separating “The Greatest” and “Smokin’ Joe,” their efforts routinely falling flat when one spiteful man or the other declined any offer to meet somewhere in the middle to negotiate a truce that would be acceptable to both.

But miracles can and do happen, sometimes when they are least expected, and such a convergence of hope and destiny occurred on February 8 and 9, 2002, in an unlikely setting, the night before and then the night of the 53rd annual NBA All-Star Game in Frazier’s adopted hometown of Philadelphia. Maybe it was because the long-hardened stances of Ali and Frazier had simultaneously softened, or maybe it was because two proud and unrelenting old warriors finally realized that continuing to snipe at one another had ceased to be interesting theater and had devolved into something that only served to diminish each.

Press agent Darren Prince, who in the mid-1990s had taken on both Ali and Frazier as clients, was an amazed witness to what many people had thought was an accord that would forever be beyond the realm of reality.

Together in 1975 to protest the murder conviction of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

“Over the course of five-and-a-half or six years, when I was affiliated with each of them, I would throw it (the suggestion of a reconciliation) out there,” Prince said in an interview with The Ring. “Some days it would gather momentum, some days it wouldn’t. There was a New York Times story that came out in 2001 where Muhammad said he would apologize to Joe for anything bad he had said about him. He said, ‘Joe’s a good man. If God ever called me, I’d tell Him I’d want Joe right beside me (in the afterlife that awaits everyone).’ That was an opening, so I called Joe and read him the story. He was amenable to a meeting, but he insisted it had to be in Philly. He said, ‘You got to tell the damn Butterfly (Joe’s most common reference to Ali) we got to meet on my turf.’ It just chilled me, the level of distrust that still existed on his part.

“But here we were, the morning before the All-Star Game, and I got a call that Lonnie (Ali’s fourth wife) and Muhammad were agreeable to a meeting if Joe was actually into it. I was told Joe, Marvis and I were invited to come to Ali’s hotel suite in Philadelphia for dinner. I was shaking with excitement and anxiety; I didn’t want to call Joe about it just yet because I had a corporate event for the All-Star Game that day. But when I saw Joe that afternoon and told him about it, he said, without hesitation, ‘All right, man, let’s go see the Butterfly. It’s time.’”

Maybe what transpired from that point on was a virtual reenactment of when Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee sat down in Appomattox, Virginia, to sign the peace treaty that ended the Civil War. For all the bitterness that had gone before, it really was time for the principals in a confrontation that had gone on far too long to recognize that the thread that had united them all along was an admiration for their shared strengths, and that continuing to bleed one another dry no longer served any useful purpose.

“From the minute we knocked on the hotel door, Lonnie greeted everybody with hugs,” Prince continued. “Joe walked over to Muhammad. They were both smiling. Ali was very overweight because of his diet and the Parkinson’s medications he was on. It was tough for Ali to get up. Joe said, ‘Hey, man, you OK? You want me to give you a hand?’ Muhammad nodded, and when Joe leaned over, they just hugged. You could see how emotional they were getting. Lonnie said, ‘Thank you for coming, Joe. Muhammad finally has found peace.’

With Ken Norton and Larry Holmes on the Champions Forever tour.

“About 20 minutes into dinner, Ali started biting his bottom lip and went, ‘Joe Fray-shuh! I’m gonna get the gorilla again in Manila!’ Joe dropped his fork and said, in jest, ‘Man, we just made peace. Do I have to whip your ass again?’

“We probably spent a couple of hours together. Howard Bingham (Ali’s personal photographer and best friend) took a bunch of photos, and then we left. But before we did, Marvis started talking. Joe stopped him and said, ‘Son, I got this.’ Everyone shut their eyes and Joe – I’ll never forget the words – said, ‘Dear Lord, we have forgotten (past animosities) and we have forgiven. I ask you to heal this man for the millions of fans and people he’s made happy around the world and his family and friends that love him. I ask you to please give him the life that he deserves and make him healthy.’ We were all in tears.”

But those private moments were played out again in a far more public setting the next night at the All-Star Game, when arrangements were made for the Ali and Frazier parties to be seated together at center court.

“Joe and Muhammad held hands when Alicia Keys sang “America the Beautiful,’” Prince said. “It was just unbelievable. Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, Allen Iverson, Kobe (Bryant), Michael Jordan, Magic (Johnson), who’s a dear friend and client of mine, all came over to take a photo with Muhammad and Joe. They understood how historic this was.

“I don’t think Joe and Muhammad even cared about the game, they were so busy chatting it up. They got a standing ovation after the players were introduced. Muhammad said to Joe, ‘We’re still two badass brothers, aren’t we?’ And Joe said, ‘Yes, we are.’”

Maybe what transpired from that point on was a virtual reenactment of when Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee sat down in Appomattox, Virginia, to sign the peace treaty that ended the Civil War.

The closest previous brush with peace in their time came in the lead-up to the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, a seemingly fertile breeding ground for compromise as both Ali, who was still known as Cassius Clay when he took a gold medal in Rome in 1960, and Frazier, a gold medalist in Tokyo in 1964, had that distinction in common. Couldn’t two American Olympic heroes just once make nice for an Olympiad held on American soil? The premise certainly seemed reasonable. But the more he thought about it, Frazier seethed when Ali, his speech slurred and his motor functions impaired by the progressive effects of Parkinson’s disease, was selected to carry the Olympic torch the last few steps to ignite the flame during the opening ceremony.

Asked by a reporter what he thought of his old archrival, whose deteriorating health had made him an even more sympathetic and culturally significant global figure, getting the high-visibility Olympic gig, a defiant Frazier sneered and said, “I wish I could have pushed him into the fire.”

Two great ring generals finally catch up, decades after their wars, at the NBA All-Star Game in 2002. (Photo by TOM MIHALEK/AFP via Getty Images)

That response by Frazier tilted public opinion, a pendulum that swung both ways at various junctures, against him again. Joe’s son Marvis, a former heavyweight contender, had been gently prodding the man he lovingly called Pop to either extend or accept any gesture toward reconciliation because … well, just because. Now an ordained minister, Marvis, as much as anyone, understood the detrimental ramifications of comments that sting as much or even more as any punch ever could. In the lead-up to the first meeting of his father and Ali, the much-hyped “Fight of the Century” on March 8, 1971, in Madison Square Garden, Ali had, in an article that appeared in Sports Illustrated, humiliated, enraged and ultimately isolated Frazier, casting him as a shuffling and mumbling Uncle Tom, an ugly and ignorant errand boy for White America. Part of the fallout from Ali’s campaign of denigration was for Marvis’ Black classmates, most of whom also had fallen under Ali’s spell, to repeat the slurs made about his father to him and his siblings. And that, Frazier decided, was something he could not and would not abide.

Exacerbating the situation was the fact that Frazier, who had ascended to the heavyweight championship after Ali was stripped of his title and his passport for refusing induction into the U.S. Army, had helped keep his future archrival financially afloat by lending him money. During the interim, Smokin’ Joe not only became chummy with Ali, he testified before Congress on Ali’s behalf and even petitioned President Richard Nixon to have Ali’s boxing license reinstated.

“[Ali would] come to my gym and call me on the telephone,” Frazier told Sports Illustrated’s Mark Kram Sr. “He just wanted to work with me for the publicity so he could get his license back. One time, after the Ellis fight (Frazier stopped Jimmy Ellis in four rounds on February 16, 1970), I drove him from Philadelphia to New York City in my car. Me and him. We talked about how much we were going to make out of our fight. We were laughin’ and havin’ fun. We were friends; we were great friends. I said, ‘Why not? Come on, man, let’s do it!’ He was a brother.”

All that changed when Ali was reinstated and the epic showdown with Frazier went from theoretical to signed-and-sealed eventuality. Although a Frazier confidante, Butch Lewis, assured Joe that Ali was just doing his thing to help build interest in a megafight that didn’t require much salesmanship, Frazier felt his humanity and manhood had been personally besmirched.

“Yes, I tommed,” a bitter Frazier said in the SI article. “When he asked me to help him get a license, I tommed for him. For him! He betrayed my friendship. He called me stupid. He said I was so ugly that my mother ran and hid when she gave birth to me. I was shocked. I sat down and said to myself, ‘I’m gonna kill him. OK? Simple as that. I’m gonna kill him!’”

Even in Frazier’s greatest moment of professional glory, the unanimous decision over Ali that was punctuated by the leaping left hook that floored Ali in the 15th round, Frazier found only a sampling of the satisfaction he believed should have been his. To many, the main thing that they recognized from what arguably was the most anticipated heavyweight showdown ever was not Smokin’ Joe’s victory, but the incredible courage Ali had shown in rising swiftly after a devastating knockdown that would have left almost any other opponent down for the count.

“My whole life, I have watched Joe Frazier get sabotaged by the Muhammad Ali propaganda machine. It’s not a balanced portrayal. It never has been.”

– Jacqui Frazier-Lyde

Then again, although they were equals, or very nearly so, in their three bouts, the other two of which were won by Ali, in the cauldron of the squared circle, there was no way Joe Frazier ever was going to come away as a full partner with a larger-than-life figure whose charisma matched his exquisite talent. Wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Halberstam: “Technically the loser of two of the three fights, [Frazier] seems not to understand that they ennobled him as much as they did Ali, that the only way we know of Ali’s greatness is because of Frazier’s equivalent greatness, that in the end there is no real difference between them as fighters.”

Being forever cast as Tonto to Ali’s Lone Ranger continued to be the burr under Frazier’s figurative saddle, and that of his children. For the New York City world premiere of the biopic Ali on December 17, 2001, one of Joe’s daughters, Jacqui Frazier-Lyde, chafed at the screen depiction of Ali being offered money by her father and refusing to accept it because he was too proud to do so.

“Yeah, right,” Frazier-Lyde said of that scene. She also complained of a passage in a promotional booklet in which the movie’s director, Michael Mann, advised prospective viewers to “forget what you think you know.”

“It’s [not] easy to forget what you think you know when you actually do know,” she said.

“My whole life, I have watched Joe Frazier get sabotaged by the Muhammad Ali propaganda machine. It’s not a balanced portrayal. It never has been. It wasn’t then and it isn’t now. Look, I have no problem with Muhammad Ali and the Ali family. I really don’t. It’s just that I wish my father’s role in Muhammad Ali’s life wasn’t always reduced or distorted. Every magazine cover I ever saw had Ali punching Frazier and not getting punched back. Why is it always that way?”

Dream Fight: Tyson vs. Frazier, by the numbers

It is that way because, like Boston Celtics superstar Larry Bird in his head-to-head matchups with the Los Angeles Lakers’ Magic Johnson, which Prince cites as the sporting world’s foremost individual rivalry outside of Ali-Frazier, Bird, a gifted but decidedly unglitzy farm boy from Indiana in comparison to the spotlight-loving Magic, found that circumstances dictate who gets to be the “A side” and who has to settle for being the “B side.” The B side can win his share of duels on the floor or in the ring, but in the court of public opinion, the Alis and Magics are almost always unconquerable.

It had been Frazier’s wish to at least outlive Ali, which presumably would have been a testament to what he believed would be his more enduring earthly staying power, but that also was not to be. Smokin’ Joe was 67 when he passed away on November 7, 2011, while Ali, although a shadow of his formerly vibrant self, hung on until June 3, 2016, when he also was outpointed by the Grim Reaper at the age of 74. But it spoke volumes as to the lasting peace they had jointly brokered that Ali, accompanied by Lonnie, made the arduous trip from his home in Michigan to attend his foremost rival’s funeral service. His appearance there was marked by solemn reverence and respect, not belligerence and bombast.

Eighteenth-century poet Alexander Pope wrote that to err is human, to forgive is divine. Given all that had passed between them, in death, as in life, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier should be forever memorialized for demonstrating that forgiveness is the balm that can salve even the most festering of real or imagined wounds.