Best I Trained: Charles Atkinson

Charles Atkinson is a respected figure in the U.K., where he performed a number of boxing-related functions, but he is best-known for working as a trainer in Thailand in the 1980s-early 2000s.

Atkinson, who was the second eldest of five children, was born in St. Asaph, Wales, though he was brought up in the Liverpool area.

He initially followed his father, Charles Sr., a decorated World War 1 soldier, into amateur boxing.

“[My father went into] the Army and got involved in boxing, and following his Army days he mixed with a lot of the top people in boxing in Britain,” Atkinson told The Ring. “One man in particular, the brother of Nel Tarleton, who was one of the greatest Liverpool boxers of all time; he was the British featherweight champion. His brother, George, was a very knowledgeable trainer; he traveled America and learnt all over the world and my father learnt a lot from him. My father went into amateur boxing as a coach; he’d boxed in the Army but not at a particularly high level.”

Charles’ father created an amateur boxing club called St. Teresa’ ABC in the early 1950s, and Atkinson was an active participant.

“The gym was situated under the church itself,” said Atkinson, who was a late starter at 14 and went on to have around 40 amateur contests, going roughly 32-8. “They used to train on Sundays while the mass was going on upstairs.

“[My father] was successful as a trainer. He created the first ABA champion ever to come from Liverpool; Frank Hope won the middleweight title in the early 1950s – he won it by about 15 minutes, because Dave Rent won the light heavyweight title. [My father] followed that with Jimmy McGrail, Jimmy Dunne and John Conteh.

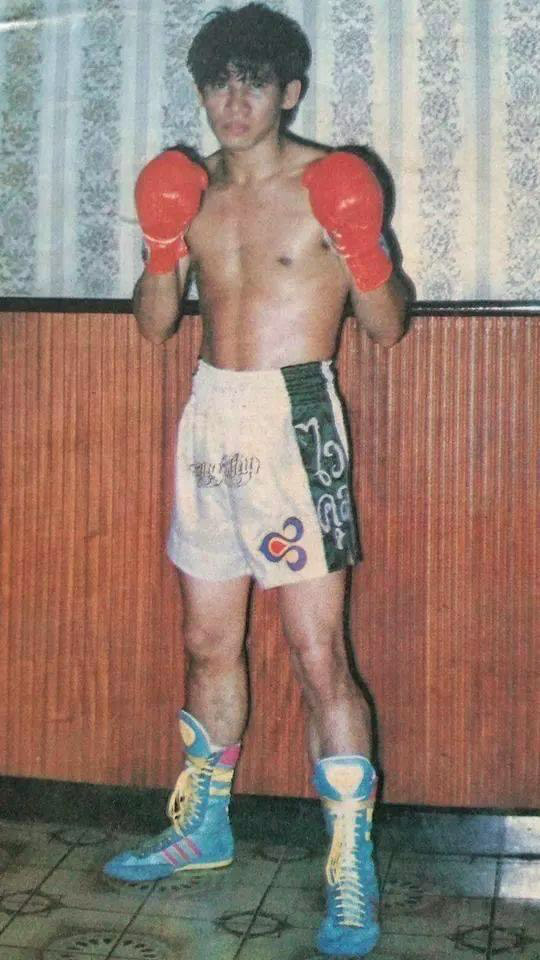

Atkinson in his fighting days. (Photo courtesy Charles Atkinson)

“I learnt a lot from my father. I boxed as a schoolboy for St. Teresa’s, and then when St. Teresa’s closed, my father became the Highway Superintendent for Kirkby Urban District. He founded Kirkby ABC, which became even more famous. I boxed for Kirkby ABC. The most I ever did as an amateur was reach the final of the ABA Youth Championships. I was never an outstanding amateur boxer but boxed at a decent level.”

Atkinson turned professional in 1962 and openly admits it didn’t work out. He walked away with a record of 2-5-1 (2 knockouts).

“As a pro, I moved to Germany at 20, [which was my] first big mistake,” he said. “I discovered that you couldn’t win there as a foreigner at that time. I lost twice to a fighter called Horst Borzowkowski. He’d had a lot of fights, but in my opinion, I won easily. The verdict went to him, but the money was five times the amount you got in England, so it compensated. That was the real start of my learning curve.”

Atkinson stepped away from life as a fighter at age 23 and became a partner in a building company and the owner of two newsstands. But as boxing often does, it pulled him back in after a period of time.

“When I saw the talent my father had and the way some of them were slipping away into obscurity or going to London, I decided I’d sign a couple as a manager,” he said. “I tried my hand at management and took out a promoters license in partnership with my brother Mike at the old Liverpool stadium, which is now demolished, unfortunately. It was the only purpose-built boxing stadium in Europe.

“I held every BBBofC license – I had boxer, promoter, agent, trainer, second – at this period after amateur boxing. I started to promote my own fighters, and Joey Singleton was one of them. He won the British junior welterweight title in only his eighth fight, in a 15-round fight against Pat McCormack, who was a knockout specialist.”

Atkinson was starting to make a name for himself and was approached by Bobby Naidoo, an official of the WBC, to see if he and his father would be interested in working with a former Kirkby ABC member, John Conteh, who had gone on to become the WBC light heavyweight titleholder.

Atkinson (left) alongside Azumah Nelson in camp. (Photo courtesy Charles Atkinson)

“I joint-promoted with Bob Arum and a gentleman called Manny Goodall the John Conteh-Len Hutchins world title fight at Liverpool stadium (in March 1977),” he said. “I made a big mistake. I was close to Everton FC and could have had Goodison Park, and I made the mistake of promoting it at The Stadium and it sold out in about two hours, which meant a small crowd. The stadium was extended, but we could still only get 4,500 in. I could have had 30,000 at Everton.”

Conteh won in three rounds but ultimately went in a different direction. Unperturbed, Atkinson went about his business. Naidoo was clearly impressed by the father-and-son duo and asked them to work with a young aspiring boxer called Azumah Nelson in the late 1970s.

“I picked him up at airport in London – he came off the aeroplane like a little boy lost – and brought him to Liverpool,” he recalled. “My father took one look at him and said, ‘This guy’s a world-beater.'”

Atkinson and his father prepared Nelson for a fight with Joe Skipper for the All-African title in December 1980 .

“Nelson’s manager at the time told me to put him on the plane for Accra three weeks before the Skipper fight, and they’d send for me,” he said. “I put Azumah on the flight, and the next time I saw him was about 15 years later and never heard from the promoter. Nelson took the fight, won it. The next thing I heard, he was in New York knocking people out. No hard feelings; Azumah had no control over it.”

“[Bobby Naidoo] contacted me out of the blue and said, ‘Thailand hasn’t had a champion for a few years. Would you be interested in going to Thailand to train boxers?'”

Naidoo appreciated Atkinson’s can-do approach and offered him another opportunity – to go to Thailand and work with boxing promoter Somphop Srisomwongse with the hope of sparking some sort of revival in the local scene.

“He contacted me out of the blue and said, ‘Thailand hasn’t had a champion for a few years. Would you be interested in going to Thailand to train boxers?’ said Atkinson. “I said, ‘I’ll think about it. It’s a long way. I’ve never been to Asia.’

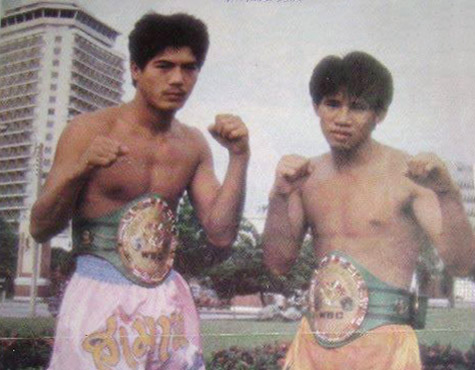

Sot Chitalada, who held the Ring and WBC flyweight titles during the 1980s. (Photo courtesy Sot Chitalada)

“We didn’t even talk money. The next thing, a week later, I had a ticket to Bangkok drop through my letterbox. I just decided to go on a whim. I flew to Bangkok, where I met a gentleman called Edward Thangarajah – also a WBC official, a great friend of the main promoter in Thailand at the time – who had a stable of fighters and was the head of sport of Channel 7 TV.”

It took Atkinson time to acclimate to his new surroundings and get things how he wanted them.

“I didn’t fall on my feet,” he said. “[Thangarajah] had a mixed stable of very ordinary fighters at the time. At first it was tough. They had one fighter (Pongpan Sorphayathai) they were trying to push for a title shot at junior featherweight, and he had a couple of wins under me. Thais are always in a hurry. They put him in with an absolute killer called Juan ‘Kid’ Meza. Meza took my boy to pieces. He had too much of everything; he was a lean, mean, no-stop attacker with a good range of punches. He stopped the Thai in three rounds and it was a comprehensive defeat.

“Thailand being what it was, there were doubts about me because I hadn’t been a magician. Somphop and Edward carried all the criticism and they kept me on working.”

Atkinson would do six-week stints in Thailand before heading home for two or three weeks. By the end of 1983, Atkinson succeeded in producing a world champion.

“They delivered a boy to me, a good amateur; he was a (1976) Olympic bronze medalist called Payao Poontarat,” he said. “He was a British-style fighter. After a couple of really good wins over Mexicans, they got a match with (WBC junior bantamweight titlist) Rafael Orono and they brought him to Bangkok. In a competitive fight, Poontarat won the decision.

“That started the whole thing off and put boxing in the limelight again, because it played very much second fiddle to Muay Thai.”

The next one to come along was Sot Chitalada, who won the Ring Magazine and WBC flyweight titles in October 1984 and reigned for much of the rest of the decade.

“[Management] didn’t want to hang around with him; they wanted to move him fast, and the guy had no experience,” Atkinson explained. “We had a couple of non-title fights and he boxed well. They put him in with no experience for the junior flyweight title in Korea (in March 1983). You couldn’t win in Korea; he lost on points to Jung Koo Chang. Sot moved up from junior fly to fly. The fighter he had to face to win the title was a fearsome fighter called Gabriel Bernal. They fought three times, one was a draw and Sot won twice.”

The supremely talented Samart Payakaroon followed, capturing the WBC junior featherweight title by knocking out Lupe Pintor in 1986. He then stopped Meza in his first defense before losing to Jeff Fenech.

“When Meza came the second time, I knew what to expect,” said Atkinson. “Samart outclassed him and then knocked him out late on.

Napa Kiatwanchai secured the WBC strawweight title and went on to make five defenses.

“He won the title in Japan – impossible!,” said Atkinson. “He wasn’t considered by the Thais as big stuff, but he was a very competent little southpaw.”

Unheralded Saman Sorjaturong, who was a 17/1 underdog, headed to Los Angeles to face IBF/WBC junior flyweight titlist Chiquita Gonzalez in July 1995. Early on, the defending champion put a beating on Sorjaturong.

“[Sorjaturong’s eye] was closed, and the ref came to the corner and I asked him not to stop it. I said, ‘Give us two more rounds.’ I had a feeling [Gonzalez] had done his best,” said Atkinson of what would later be named The Ring’s Fight of The Year. “And what did the little guy do? Instead of covering up, he went straight out and knocked out Gonzalez. The worst thing Gonzalez could have done was take a right hand from Sorjaturong. The right hand that finished it caused a gash from the bridge of his nose to his forehead. He actually lifted Gonzalez off his feet. [Gonzalez] got up and he got battered relentlessly. [Sorjaturong] was the hardest right-hander puncher of all the fighters. Gonzalez never fought again.”

Atkinson trained Mary Kom for the 2012 Olympics, in which Kom would win a bronze medal. She was defeated by future WBO flyweight titleholder Nicola Adams. (Photo by Punit Paranjpe/AFP via Getty Images)

Sirimongkol Singmanasak claimed the WBC bantamweight title and made two successful defenses but struggled mightily, like many of his stablemates, to make weight and lost his title to popular Japanese fighter Joichiro Tatsuyoshi in late 1997. Over the next couple of years, he churned out many wins before adding the WBC junior lightweight title. He lost the belt in his second defense against Jesus Chavez (UD 12) but went on to compete until 2021.

“I can’t speak highly enough of Thailand and Somphop Srisomwongse. I was always well treated,” said Atkinson. “They may have had their own views on weight reduction but generally always took great care of their boxers’ welfare and maintenance. I never remember them relinquishing a title without defending it in the ring. They moved mountains to establish their fighters in world boxing during my period there and did their best to give them opportunities in their home country.”

For around a decade, Atkinson was an adviser for television company ITV, which broadcast many of the fights from Thailand involving his fighters.

Atkinson was hired by a sponsor to privately train Mary Kom, and he successfully guided her to a bronze medal for India at the 2012 London Olympics. He is still involved in boxing with a sport supplements and boxing equipment company called Impact and with the Kirkby amateur club, which Richie Lloyd initially ran before his son John took over. It is one of the finest amateur clubs in the U.K.

Atkinson is married, has five children and four grandchildren and lives in Anglesey, North Wales.

He graciously took time to speak to The Ring about the best he trained in 10 key categories.

BEST JAB

Sot Chitalada: “It was accurate and hard, coupled with good movement. So, when he jabbed, you couldn’t counter.”

BEST DEFENSE

Samart Payakaroon: “You couldn’t hit him. He didn’t have a mark on him. That’s why he became a movie star.”

BEST FOOTWORK

Chitalada: “His footwork was graceful. He could do it around the outside of the ring and he could do it at close quarters. He had all those Ali shuffles. He was light on his feet, he was evasive, his timing was perfect.”

BEST HAND SPEED

Chitalada: “The speed he’d put combinations together – he was a natural combination puncher. It wasn’t just speed, it was accuracy.”

SMARTEST

Chitalada: “He was a thinking fighter. He would set you up for that attack, he’d put them into position to unload on them. He was a brilliant defensive boxer. He was a frustrated slugger, he loved to slug – I hated it. He got in wars. He was good to watch.”

STRONGEST

Chitalada: “His stamina, considering the strains he was under in terms of weight, he was the most durable. He was one of the toughest little guys I ever came across.”

BEST CHIN

Singmanasak: “He had a cast-iron chin until he was completely drained by weight-making and became vulnerable. He was game and courageous. He was very difficult to hit anyway, but when he did get hit, he could hold a shot very, very well. Hard as nails. He eventually boxed as a pro right up to light heavyweight.”

BIGGEST PUNCHER

Saman Sorjaturong: “He was a natural right-hand puncher. He wasn’t a big swinger; they weren’t traveling far. He could knock you dead. He knocked a lot of people out. He was a concussive puncher. They could all punch a little bit, but this guy carried the knockout drops.”

BEST BOXING SKILLS

Payao Poontarat: “Poontarat had to be a good boxer to be an Olympic medalist. Poontarat was a beautiful boxer. Stand up, left jab, right cross, left hook, three-punch man.”

BEST OVERALL

Chitalada: “You have to go by overall results, therefore it’s a close call between Sot Chitalada and Sirimongkol Singmanasak. Both achieved a lot, despite considerable weight problems later in their careers. One thing about Chitalada which may give him an edge, he fought the toughest and best out there. Having said that, Singmanasak won two titles, so it’s a close call.”

Questions and/or comments can be sent to Anson at [email protected].