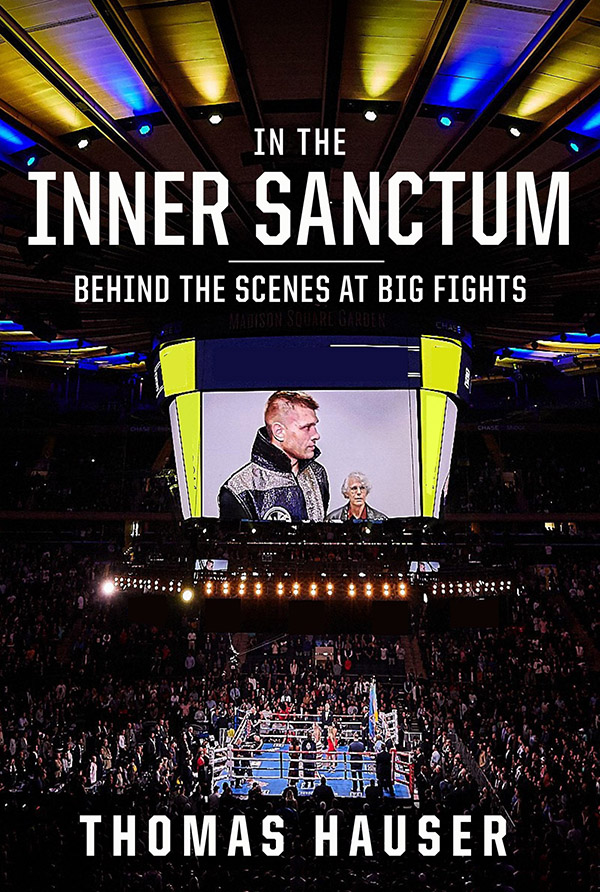

The Inner Sanctum: Thomas Hauser’s latest book gives rare glimpses of boxing life

Author Thomas Hauser is what I call a “Q-and-Q” writer, a reference to the prodigious quantity of copy he has produced during his distinguished career, much of which deals with boxing, as well as the quality of his prose, which is uniformly excellent. Not for nothing was he an inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2020, and his trophy room, if indeed his New York City apartment has one, would be filled to overflowing with all his journalism awards.

Hauser’s versatility in selecting his topics hardly needs to be cited, but one of his non-fiction books, Missing, was the basis for a 1982 film which was nominated for four Academy Awards, with Jack Lemmon taking the Oscar for Best Actor. And although Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times stands as the ultimate dissertation of “The Greatest” as both boxer and societal touchstone, 32 of Hauser’s 56 published books dwell on fights and fighters, emblematic both of his personal fondness for the sweet science and the source material’s nearly bottomless well of tales begging to be told.

The most recent of Hauser’s lengthening line of boxing anthologies, In the Inner Sanctum: Behind the Scenes at Big Fights, is a chronological listing of events in which he was allowed the rare privilege of sharing the private space of mostly well-known (but not exclusively) fighters both before they entered the ring and after they returned to their dressing rooms in victory, defeat or neither, given the possibility of a mutually dissatisfying draw. The first time Hauser was allowed such uncommon access was with Billy Costello in 1984, while he was researching his introductory boxing book, The Black Lights: Inside the World of Professional Boxing. Hauser gives credit not only to Costello, but to Mike Jones, Victor Valle and Saoul Mamby for generously giving their time and knowledge to him, seeds that 13 years later would blossom into a series of anthologies published by the University of Arkansas Press that detail the hopes, dreams, frustrations and anxieties of boxing people to which the public is seldom afforded totally truthful insights. In widely covered press conferences designed to hype an event, headliners know their function is to help drive interest and revenue streams; these are frequently false forums for bellicosity, bravado and belligerence.

The most recent of Hauser’s lengthening line of boxing anthologies, In the Inner Sanctum: Behind the Scenes at Big Fights, is a chronological listing of events in which he was allowed the rare privilege of sharing the private space of mostly well-known (but not exclusively) fighters both before they entered the ring and after they returned to their dressing rooms in victory, defeat or neither, given the possibility of a mutually dissatisfying draw. The first time Hauser was allowed such uncommon access was with Billy Costello in 1984, while he was researching his introductory boxing book, The Black Lights: Inside the World of Professional Boxing. Hauser gives credit not only to Costello, but to Mike Jones, Victor Valle and Saoul Mamby for generously giving their time and knowledge to him, seeds that 13 years later would blossom into a series of anthologies published by the University of Arkansas Press that detail the hopes, dreams, frustrations and anxieties of boxing people to which the public is seldom afforded totally truthful insights. In widely covered press conferences designed to hype an event, headliners know their function is to help drive interest and revenue streams; these are frequently false forums for bellicosity, bravado and belligerence.

Hauser mentions many fight people by name in the 35 entries, beginning with the November 22, 1997, pairing of George Foreman (in what proved to be his final bout) and Shannon Briggs at Atlantic City’s Trump Taj Mahal, and continuing through the November 2, 2019, clash of Canelo Alvarez and Sergey Kovalev in Las Vegas’ MGM Grand Garden Arena, but the main characters are always the principals who will swap punches that night – and, since the author has yet to find a way to be in two places at once, his status as a favored visitor in a particular dressing room is either by his choice or that of a consenting fighter. It is a testament to Hauser’s gift for anticipation, luck or some combination thereof that it almost always seems he finds himself in the right place to glean the most interesting information.

Although George Foreman was the logical choice to get the deeper, more probing look from Hauser for what Big George had previously announced would be his final bout, regardless of outcome, and had exercised veto power by refusing casino magnate and future President Donald Trump admission to his dressing room, much of the story is centered on Briggs, a highly regarded heavyweight prospect who would either end the night on the cusp of superstardom or as an exposed wannabe who lacked what it took to take the step up that separates the merely good from the certifiably great. Curiously, Briggs, the beneficiary of a highly dubious and unpopular 12-round majority decision, seemed almost unaccepting of the gift nod he had received on the scorecards.

The unapologetically blunt Teddy Atlas, who trained Briggs, threw shade on his fighter for deficiencies he said no trainer was capable of fixing. “Shannon was always more interested in finding the easy way of doing things,” Atlas said. “Physically, he worked hard, but mentally it was all a big con with him. He was great at schmoozing with (primary financial backer) Marc Roberts. You can schmooze investors. But sooner or later in boxing, you meet an opponent you can’t con in the ring, like Darroll Wilson (who had stopped Briggs in three rounds on March 15, 1996) … a weak mind and panic can bring on a lot of things. I tried to help Shannon become a real fighter. Not a phony, a real fighter.”

It is a testament to Hauser’s gift for anticipation, luck or some combination thereof that it almost always seems he finds himself in the right place to glean the most interesting information.

Another physically imposing heavyweight contender, Michael Grant, assumed the Briggs role for his April 29, 2000, challenge of WBC heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis in Madison Square Garden. At 6-foot-7 and 250 pounds, Grant, 27, a former multi-sport star in his athletic development, was being hyped by some as the most physically gifted big man boxing had yet seen. But there were some, even in Grant’s camp, who wondered if he had the inner drive to maximize his imposing combination of size and strength. Against Lewis, who would go on to be recognized as perhaps the premier heavyweight in a golden age for the division, Grant was knocked down three times in the opening round and stopped in the second.

“The problem is that Michael doesn’t really like boxing,” one of his cornermen, Bobby Miles, assessed as Grant’s once-promising career began to trend downward. “It’s just not something he likes to do. And he still thinks like an athlete, not a fighter. If you’re a fighter, you have to approach each fight like a gladiator in the Roman Colosseum. You have to be mean. You’re fighting for survival. Michael just isn’t mean enough.”

Some of Hauser’s stories depict great fighters at the height of their remarkable powers, and at their career nadir once their skill sets dissipate or they refuse to adapt to shifting realities. Roy Jones Jr. is so variously depicted, including the full blush of his glory, when he moved up two weight divisions to befuddle the much larger, but far less talented John Ruiz to win the WBA heavyweight championship by wide unanimous decision on March 1, 2003, at Las Vegas’ Thomas & Mack Center. Like Muhammad Ali, Jones fought unconventionally, carrying his left hand low and leaning straight back from punches instead of twisting or stepping away from them. Like a downsized version of a peak Ali, the young Jones did a lot of things technically wrong but almost always found a way to make them turn out right.

HBO analyst Emanuel Steward understood that a one-time-only, bulked-up Jones was hardly a natural heavyweight, but neither were some other legendary champions in boxing’s marquee division. After RJJ had flummoxed Ruiz, Manny opined that Lennox Lewis still was the best big man, but “if Jones could be transported back in a time machine, he would beat the smaller heavyweight greats like Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano.”

Jump forward to May 15, 2004, and Jones, who had sapped himself taking off the weight he had put on for Ruiz to return to light heavyweight, was now a shadow of what he had been in losing on a one-punch, second-round knockout to Antonio Tarver in the middle installment of what proved to be a trilogy. This Jones was not necessarily ancient at 35, but his refusal to alter his trademark style, born of obstinance and pride, would accelerate his decline from gladiator of the gods to something considerably more human. Even a year before his comeuppance from Tarver, who would beat him again in the rubber match, HBO analyst Larry Merchant had said, “I don’t get a feeling of magic from Roy Jones anymore.”

Canelo Alvarez relaxes in his dressing room before his fight against Sergey Kovalev in November 2019.

Bernard Hopkins and England’s Ricky Hatton are the only fighters to be featured in four separate stories in the compilation assembled for this book, but Jones and Canelo Alvarez share top billing for most dressing-room appearances by Hauser, with three apiece. The frequency of mentions for certain fighters could owe to how obliging some were to opening their door to him, some of their trade being notoriously leery of media observers. Floyd Mayweather Jr., for instance, gets a mention in only one story, and not in the prime position, but that could be because he wanted to reserve the space around himself for those in his crowded inner circle.

Not all of the entries are of matchups involving superstars, or even fringe stars. Hauser knows that even relative outsiders can have something worth writing about, thus he reserves space for the likes of Anthony Ottah, Ernest Johnson and Seanie Monaghan.

It should be noted that not all of Hauser’s dressing room stakeouts are depicted in this particular volume. A more comprehensive breakdown of his inner sanctum visits would show Roy Jones Jr. and Sergio Martinez leading the way with six apiece, followed by Kelly Pavlik with five and Manny Pacquiao, Jermain Taylor and Paulie Malignaggi with four apiece.

Bernard Fernandez, named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Observer category with the Class of 2020 was the recipient of numerous awards for writing excellence during his 28-year career as a sports writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. Fernandez’s first book, “Championship Rounds,” a compendium of previously published material, was released in May 2021. The sequel, “Championship Rounds, Round 2,” with a foreword by Jim Lampley, is currently out, with the third such volume, “Championship Rounds, Round 3,” with a foreword by John Schulian, scheduled to be released within the next week. All three anthologies can be ordered through Amazon.com and other book-selling websites and outlets.

More on RingTV: An Inductee Experiences the International Boxing Hall of Fame, by Thomas Hauser