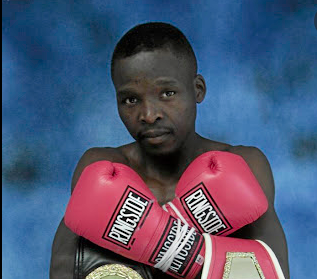

Rest in power and peace, Lehlo Ledwaba

Lehlo Ledwaba is remembered, unfairly, within boxing circles more so for losing to a fighter who went on to become a massive superstar than his quite-solid resume in totality.

The South African boxer campaigned as a pro from 1999 to 2006, held the IBF super bantamweight title from ’99-’01, and should be known for much more than losing to Manny Pacquiao in June 2001. Should, but isn’t, because boxing isn’t a “fair” sport, life is not fair, there’d be no kids with cancer if it were.

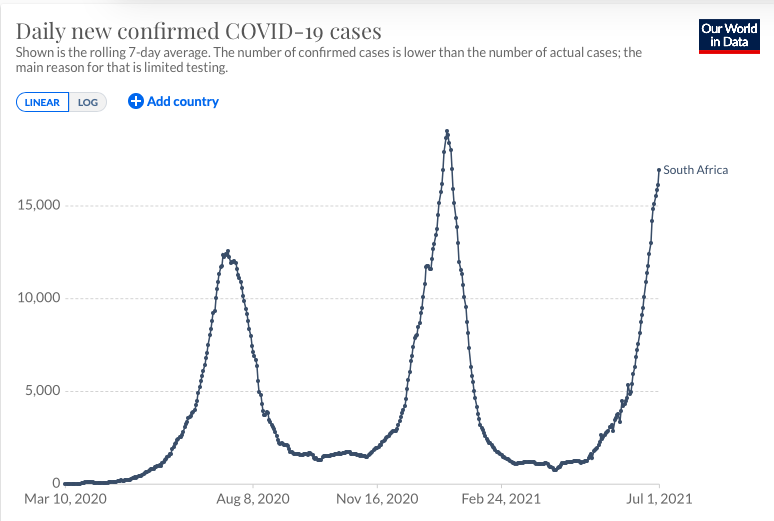

The world turns, and churns out droughts and famines that savage innocents galore. And starvation decimates populations as despots sock away loot from their nations’ treasury and aren’t even moved enough to shrug. And a global pandemic still rages on 1 1/2 years after it started, and removes good and great people from their loved ones. Not fair. On Friday, Ledwaba passed away, from COVD-19, in South Africa.

People are processing the news that this good human being and better-than-good boxer had died way too soon, at age 49.

Ledwaba fought with skill, technique that was real good, but not cookie-cutter, and power. It’s apt, maybe, that we honor his memory by pointing out that less wealthy nations don’t have the means to face down the pandemic that “greener” nations do, and suffer harshly as a result.

And some know, and more should know, that he came into the boxing realm as so many others have before him. Ledwaba didn’t live in luxury in Meadowlands, Soweto, South Africa. He looked up to his mom, who worked tirelessly to provide in their single parent setup. “I worked hard to make sure I bettered my lifestyle,” he told reporter Anson Wainwright. “I wanted to help my brother, two sisters and my mother. To make sure I [could one day] buy my mum a house.”

He kept on moving up the ranks, in the amateurs, then the pros.

Ledwaba, born “Lehnohonolo,” aced tests in his homeland, with the May 29, 1999 unanimous decision victory over John Michael Johnson in the province of Gauteng, South Africa being a culmination triumph. That win had an extra element of emotion flavoring it–Ledwaba learned the trade while the cruel practice of apartheid on a daily basis tried to reduce the pride and dignity of SA blacks. Didn’t work on Ledwaba; his beaming smile was at max wattage in the ring at Carousel Casino in Hammanskraal as he held the world title strap.

He piled up wins defending the 122 pound strap, downing Edison Valencia Diaz, Ernesto Grey, Eduardo Alvarez, Arnel Barotillo and Carlos Contreras (click here to see tape from Ledwaba-Contreras). Those victims saw a calm pugilist who impressed with far-above-average accuracy–he placed his tosses with surgical directness–and ability to mix his shots, and put together smooth combos. Smooth, but sharp, he mixed speeds well, but his power strikes had real oomph on them.

Ledwaba was 29 and most highly respected as he walked to the ring to defend the title against a blonde-frosted Manny Pacquiao, in Pacquaio’s first fight in America. Manny was 24, and had a wealth of experience, but not against the caliber of names Ledwaba had taken on. Would this Pac…Pacq..how do you spell it, how do you say it?…would he not be befuddled by Ledwaba working the angles, taking advantage of Manny’s hyperactive style, which would read as over-aggressive and ripe to be exploited by the South African stylist?

Experience didn’t help Ledwaba (33-1 at the time) as he sought to adapt to the darting manner of a left-hander. He’d been prepping to meet an orthodox foe, and Pacquiao (32-2 coming in) got a late invitation, four days from fight time, to seek to impress American fans tuning in to HBO for an Oscar De La Hoya main event. “Pacquiao wasn’t known in the U.S until he fought me,” Ledwaba told Wainwright in 2020. “At that time, I was at the peak of my career. I was regarded as one of the best junior featherweights around. For Manny to beat me was a breakthrough, so I would say I introduced him as far as America is concerned.”

Manny moved, and Lehlo knew real quick his flat-footed self would not find it easy to defend against the late replacement. By the second round, Lehlo’s nose was busted. He of course soldiered on with valor.

Ledwaba admitted that the Pacquiao attack impacted his psyche.

His love affair with boxing dimmed some, he realized that while he wasn’t “old,” he also wasn’t young, and young guns were starting to flood the zone with some nasty weapons.

But a bit over a year after the defeat at the hands of the future Senator from the Philippines, to celebrate his 30th birthday, he defeated fellow South African Vuyani Bungu. Ledwaba grabbed a WBU featherweight crown, after elevating in the ranks of junior bantamweights and junior featherweights, and he did it in South Africa, cementing harder his local legacy.

He fought six more times, including two battles with one of those younger guns, a South African talent three years his junior, Cassius Baloyi. Ledwaba’s last ring showing came in 2006.

He stayed in the boxing world, Ledwaba funded a fight gym in Soweto, South Africa, and worked the promotional side as well. He’d now and again think about what might have been, if his momentum had been allowed to build, if he hadn’t been the one to be the fuse that lit the Pacquiao fireworks.

Hopefully, Ledwaba fully comprehended that plenty of folks knew of him not as anyone’s steppingstone. His nickname was “Hands of Stone,” and almost no one scoffed, saying it was a sacrilegious slap at Roberto Duran.

Here’s hoping Lehlo Ledwaba, the fighting pride of Soweto, realized the depth of the positive impact he had on boxing, and that he rests in power and peace.