Jimmy Young: The Great Opponent

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of The Ring Magazine.

JIMMY YOUNG NEVER BECAME CHAMPION, BUT HIS BOXING SKILLS AND HEART PROVIDED A STERN TEST FOR SOME HALL OF FAME HEAVYWEIGHTS

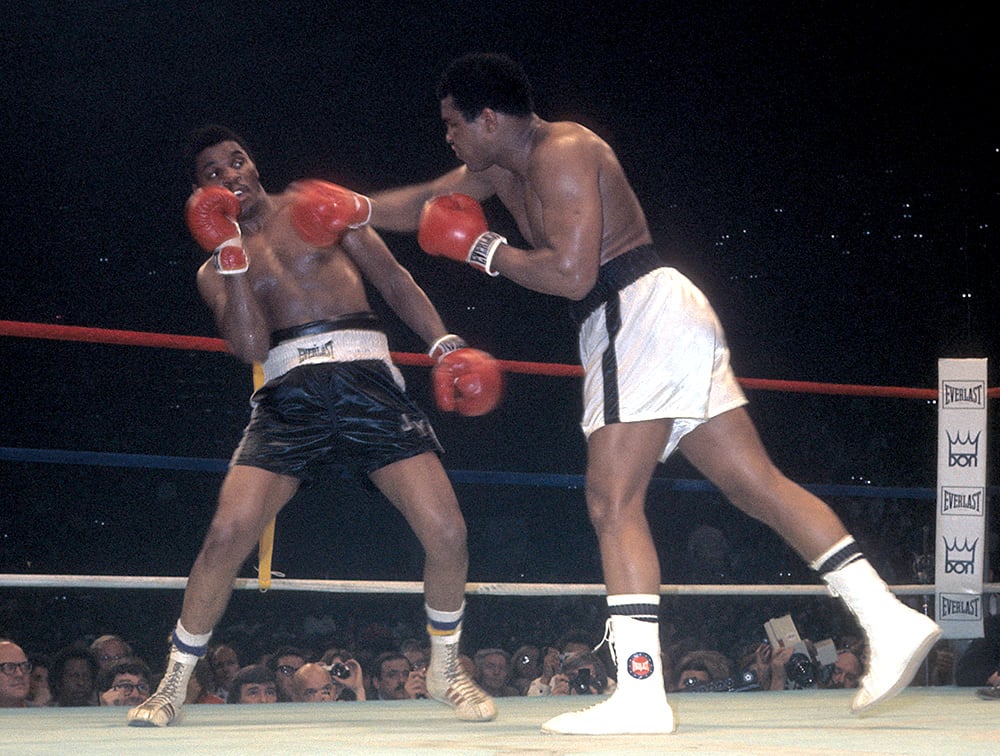

It was your typical Muhammad Ali fight. There was showboating, quick fists, multi-punch combinations, dazzling footwork and an almost psychic anticipation when it came to defense. A capacity crowd of 12,472 fans had fully expected to see these hallmarks on display at the Capital Centre in Landover, Maryland, on April 30, 1976. It was “The Greatest” after all. However, the disconcerting thing about this particular bout was that it was Ali’s opponent who was executing.

Young in 1977. (Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

The opponent’s name was Jimmy Young.

The 34-year-old Ali was just one fight and seven months removed from his epic triumph over archrival Joe Frazier in “The Thrilla in Manila,” which had been their third and most brutal encounter. In the interim, he had halted Belgian no-hoper Jean Pierre Coopman in five rounds in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Therefore the undisputed heavyweight champion was now required to face a legitimate contender.

Young had the reputation of a smart and sophisticated technician, and he was rated No. 3 according to Ring Magazine. However, Ali – who had defeated future Hall of Famers Ken Norton, Frazier (twice) and George Foreman within the previous three years – was now firmly established in the role of giant-killer and, perhaps understandably, he viewed Young as light work. Ali’s official weight of 230 pounds (the heaviest of his career at that time) and matching girth highlighted his flippancy during training camp. But taking this particular challenger for granted almost backfired. Young boxed brilliantly at times, whereas Ali was listless and inaccurate, and the unanimous decision scores of 72-65, 71-64 and 70-68 flattered him.

Many ringsiders felt that the 27-year-old Young deserved the victory, and not for the last time it was perceived that Ali’s popularity, and not what was left of his fighting skills, helped him to retain the title. The tragedy of this story is that it was Young’s first and final world title fight. Despite enjoying more success at the top level, he fought on for 14 more years, sustained irreversible physical damage and died from a heart attack at the age of 56. But how would Young’s story have played out had the judges appreciated his light-hitting but razor-sharp boxing style? What if he’d gotten that decision against the great Ali?

“Ali was just playing around, laying on the ropes and letting Young do whatever he wanted to do,” said Philadelphia trainer Stephen Edwards, who watched a long-retired Young spar in the mid-1990s. “But in reality, Ali was old and shot. He didn’t feel like dealing with a fast boxer at that time, so he just went through the motions. He played the judges and played the fans and made it look like he was playing with Jimmy Young. In truth, Ali didn’t have the energy to deal with a younger guy at the time.

“The thing is, Ali was an icon, whereas Jimmy Young is looked upon as a good fighter with a bad record (Young was 17-4-2 going into the Ali fight). It’s easy to take the fight away from Jimmy Young. It’s one of these things where, ‘OK, we’re gonna take the fight away from Jimmy Young; nobody cares. It’s not like he’s a big ticket-seller or a big moneymaker. He’s just a talented fighter with a bad record. Nobody cares if he wins a fight or not.’”

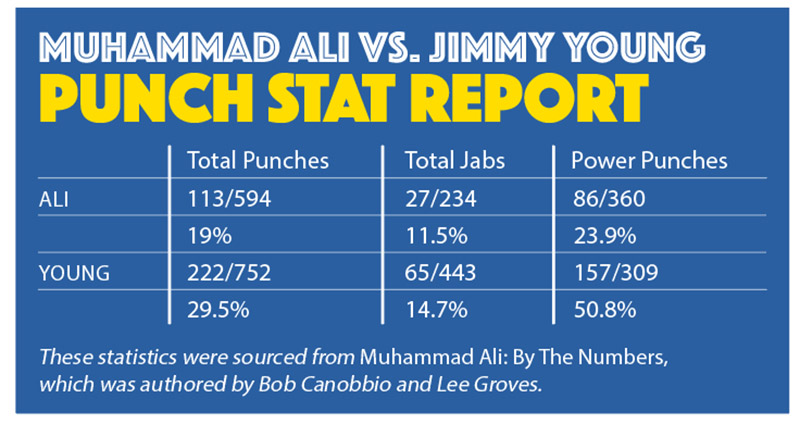

Muhammad Ali was made to miss again and again by the slick and elusive Young (see numbers below).

Young was born in Philadelphia on November 16, 1948. At 14 years old, he began boxing at the 23rd Police Athletic League Center as a means of defending himself after thugs stole his radio. Athletically gifted and astute, he managed to snare two New Jersey Golden Gloves titles but ultimately decided to forgo a potentially successful amateur career by turning professional in October 1969. His management team was hardly what you would call experienced: Jack Levin, a Philadelphia electronics wholesaler; and Ray Kelly, who was in the automobile leasing business. Young was trained by a knowledgeable but unknown coach by the name of Bob Brown, and he began his professional ascent in relative anonymity. However, he would soon be fighting out of Joe Frazier’s Gym in North Philadelphia and would frequently spar the great champion.

But without attractive amateur credentials or a shrewd matchmaker, Young was often in over his head. He was outpointed by fellow novice Clay Hodges in his third fight, but setbacks to more experienced campaigners like Roy Williams, Randy Neumann and Earnie Shavers were forgivable. Shavers stopped Young in three rounds, but that result triggered a turning point, as Young would go unbeaten in 12 fights over three years. He was robbed of victory in a rematch with Shavers and had to settle for a draw, but it was a virtuoso performance over No. 5-rated heavyweight Ron Lyle in Hawaii in February 1975 that saw Young establish himself as a serious contender. “I have always had confidence, but after I beat Lyle, I knew I was on my way,” Young told The Ring in 1977. “I showed people what a boxer who is always thinking can do to a fighter who’s just in there to take you out with one punch.”

“Jimmy Young, as good as he was, was never considered to be anything more than the opponent.”

– George Foreman

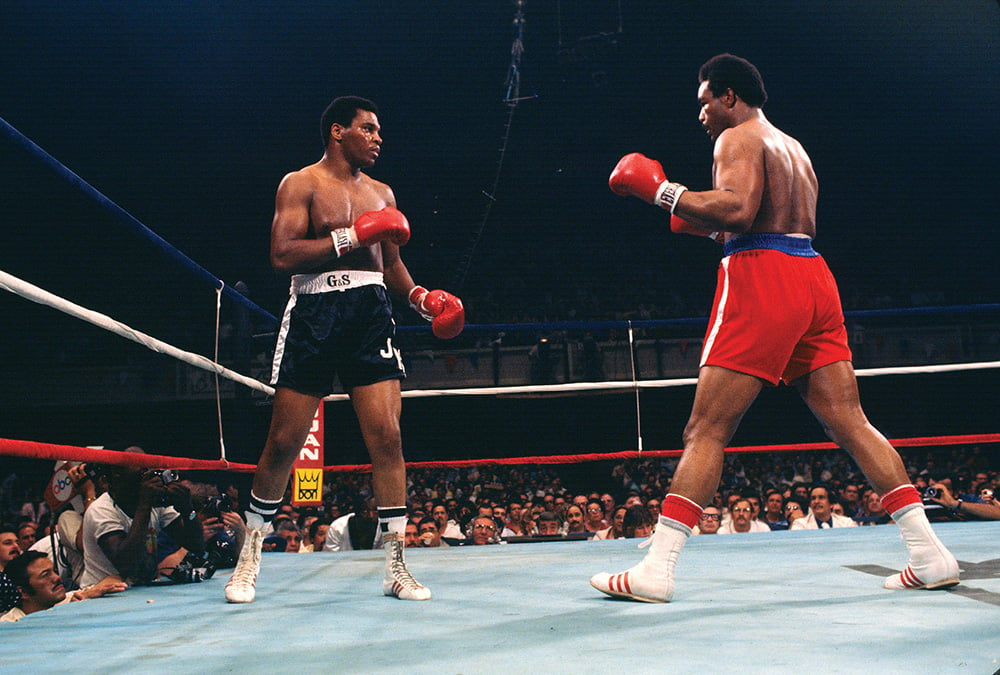

Ironically, it was Lyle, coming off this loss, who was granted a world title bout against Ali in May 1975, and Young had to wait another full year for his opportunity. Following the bitter disappointment of his controversial defeat to Ali, Young outclassed Lyle for a second time before being matched against monstrous former champion George Foreman. It proved to be the highlight-reel performance of his entire career.

“Jimmy Young was very good at operating in the ring,” said Foreman, who dropped a unanimous decision in March 1977. “He was the boxer, the actor; he could pull tricks; he was the wrestler. You know when wrestlers act like, ‘Oh, he hit me illegally,’ then put on a show? I can remember Young right now, holding the back of his head [and telling the referee], ‘He hit me! He hit me!’ (laughs) He needed a little bit more, but he was a fine boxer. He had nothing physically, but he was elusive and he kept thinking. His whole thing was boxing, boxing, boxing. Young had it all, and he got the decision over me.”

The Foreman win would be named Ring Magazine Fight of the Year, and the seventh frame would receive Round of the Year honors. In that session, Foreman blasted Young with a lethal left hook and went all out for victory. “At the time, I thought it was all over,” recalled Young afterward. “I can remember telling myself, ‘Well, it’s all over.’ But then I regained my composure and I said, ‘No, it’s not all over; this big lug can’t finish me off.’ Instead of running away, I decided to go after him.”

Despite being badly hurt and on the precipice of a knockout loss, Young rallied and was outworking Foreman when the bell rang to end the round. History remembers the bout as an aberration, a blemish on Foreman’s Hall of Fame resume that shouldn’t be there, primarily because “Big George” had a spiritual awakening in the dressing room afterward and retired for 10 years to pursue a career as an evangelist. That is a disservice to Young.

READ Best I Faced: George Foreman

“It’s a real win,” countered Edwards in earnest. “Obviously Foreman had issues after the Ali defeat, but, at the time, he only had one loss, he was a big favorite, and Young earned that victory. Everybody has an excuse for why certain things happen. No fighter can be in the zone for every single fight of their career. Foreman had dropped off a little bit from the form he showed against Frazier and Norton, but we can’t take credit from Young because Foreman was going through some mental issues. He has to get over it. Foreman was still a young man, 28, so he wasn’t old. Young deserves the victory, but there’s just some guys that will never get the credit that they deserve. Foreman wasn’t on his best form, but he was still a formidable guy. Not just anybody could go in and beat Foreman like that, so Young deserves a lot of credit for that win.”

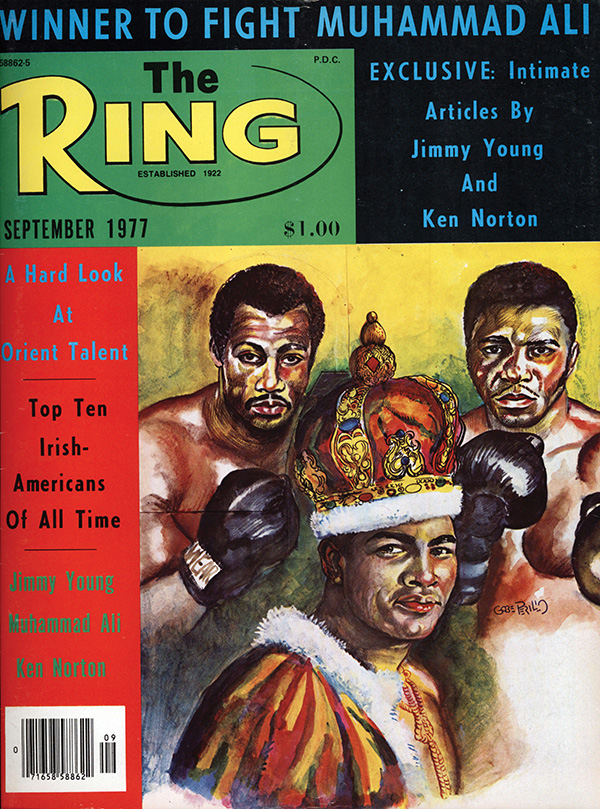

One would think that a triumph of this magnitude would earn Young a second world title fight, but it was not to be. Ali, further into his decline, was in no rush to let Young float like a butterfly and sting like a bee, so he chose novice Alfredo Evangelista and Shavers for the remainder of his 1977 schedule. In a time where dinosaurs ruled the heavyweight landscape, Young, a tidy but one-speed boxing savant, was granted no favors.

“Sadly, it all depends on how you come up,” said Foreman in relation to Young’s plight. “With me, I won the Olympic gold medal, and the talk was that George Foreman would be the next heavyweight champion of the world. I’d have three professional fights and the talk was still, ‘Here’s George Foreman, the next heavyweight champion of the world!’ But some fighters are only viewed as an opponent and they find it hard to shake that off with the judges, with the referee, with the audience. Jimmy Young, as good as he was, was never considered to be anything more than the opponent.

In a career-best win, Young outscored former heavyweight champion George Foreman in March 1977. (Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

“With me, I fought 37 times before I went in against Joe Frazier [for the heavyweight championship], and every time I went into the ring, the man across from me was an opponent. They were good fighters, but once you get tagged as the opponent, there’s a line that you cross and it’s hard to get back. Maybe you took a fight because you wanted to make a down payment on a truck. Maybe you just needed money, but you weren’t in shape. That’s what an opponent does.”

Young’s final big moment was a championship elimination bout against Ken Norton on November 5, 1977, at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Once again, the Philly magician was in sparkling form, outmaneuvering his opponent throughout much of the contest and landing much cleaner shots than Ali managed through three fights totalling 39 rounds with the Adonis-like Californian. A devastating late-rounds body attack by Norton convinced two of the three judges that he’d done enough, and the more marketable fighter escaped with a split decision … again. However, as Edwards pointed out, if Young had picked up that win, nobody could have complained.

In the final analysis, Young faced Ali, Foreman and Norton – three legends of the golden era – and he more than held his own. If he’d beaten Norton, it is highly likely that he would have been upgraded to full WBC champion, as Norton was when Leon Spinks gave Ali the chance to avenge a stunning upset loss rather than fulfill a pre-agreed WBC mandatory obligation. Spinks would ultimately defend the WBA version of the title against Ali, and Norton would make his first WBC title defense against the emerging Larry Holmes, losing a classic war via 15-round split decision. But what if Young had faced Holmes?

“I think Young would give Holmes fits, because boxers don’t like other boxers,” reasoned Edwards. “Norton was past his prime when he fought Holmes – way past it. He was almost 35. And look at the trouble he caused him. Boxers, guys who can box really well, guys who have good jabs and things, they don’t like facing other guys that can do that. Larry Holmes is a great champion, but he doesn’t like boxers. Look at the trouble he had with Tim Witherspoon’s jab. Look at the trouble he had with Carl Williams; Williams drove him crazy. So he had a lot of trouble with boxers. Holmes would have won a decision because of his record and because he’s a bit more forceful, but I think Jimmy Young would have probably given him fits. That would have been a really tricky fight for Holmes.”

“When you go back to those days and talk about great fighters, Jimmy Young was one of those great fighters.”

– Larry Holmes

Holmes would reign from 1978 to 1985, and he is generally regarded as one of the finest heavyweight champions of all time. In terms of his physical attributes, he had adept movement, terrific hand speed, a dynamite left jab and a powerful right cross. Like many of the great heavyweights who came before him, “The Easton Assassin” was also durable, courageous and full of fight. As a result, Holmes, who went 48-0 before sustaining a single blemish on his record, has never been bashful when it comes to expressing his greatness. The former champion’s modesty was therefore unexpected when he was asked for his thoughts on a mythical matchup between himself and Young, with whom he sparred dozens of rounds in the early and mid-1970s.

September 1977 cover of The Ring.

“That fight would probably end up a draw,” Holmes disclosed to The Ring. “Jimmy and I would have been a good fight, because I knew how to stay away from him when he was getting ready to punch and he was the same way with me. Jimmy Young was a good fighter, man. You couldn’t just go in there and beat him up. He was a good fighter who knew how to block punches, and he knew how to hold when he got in trouble.

“When you go back to those days and talk about great fighters, Jimmy Young was one of those great fighters. He had an awkward style that could throw you off, and he proved himself against Ali, George Foreman and Kenny Norton. Some people might not remember him, but I remember him, and that’s all that matters.”

The sport of boxing never crowned Young as champion or made him a millionaire. Instead, it tossed him head-first into a deadly division replete with great fighters and blatantly refused to appreciate his defensive style. He was betrayed on the scorecards in his biggest fight and ultimately betrayed further when boxing claimed his health in retirement. Perhaps praise from the kings with whom he shared the ring is the nearest we’ll get to a happy ending.

“His heart was underestimated,” said Foreman in earnest. “This man got in the ring with Ron Lyle and George Foreman. You give Jimmy Young a fight and he’ll take it. The man had heart, and he wasn’t afraid of anyone.

“Jimmy Young was a good boxer, smart and educated in boxing technique, and he knew how to protect himself. If he hadn’t been tagged as an opponent, it would be a former champion of the world we’d be talking about. Isn’t that the most remarkable story? I’m glad that someone is writing about Jimmy Young, because he was a remarkable man.”

Tom Gray is Associate Editor for Ring Magazine. Follow @Tom_Gray_Boxing

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE