THREE MINUTES

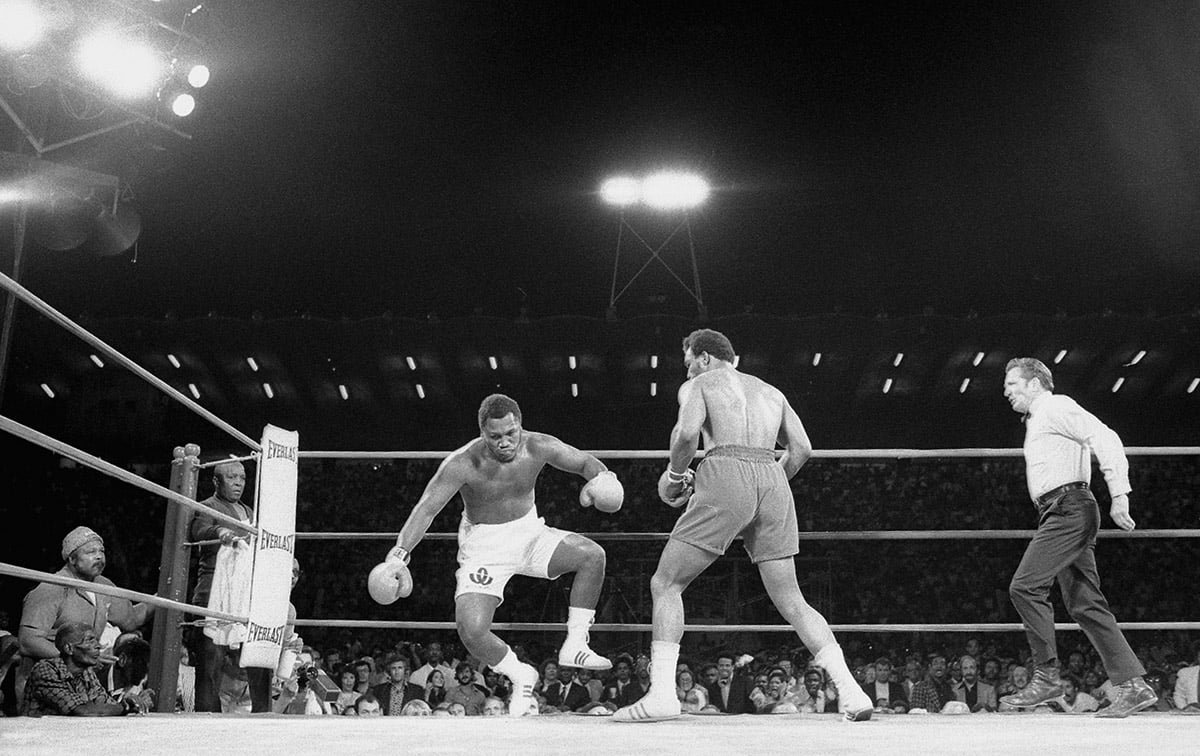

FRAZIER VS. FOREMAN 1, ROUND 2 (JANUARY 22, 1973)

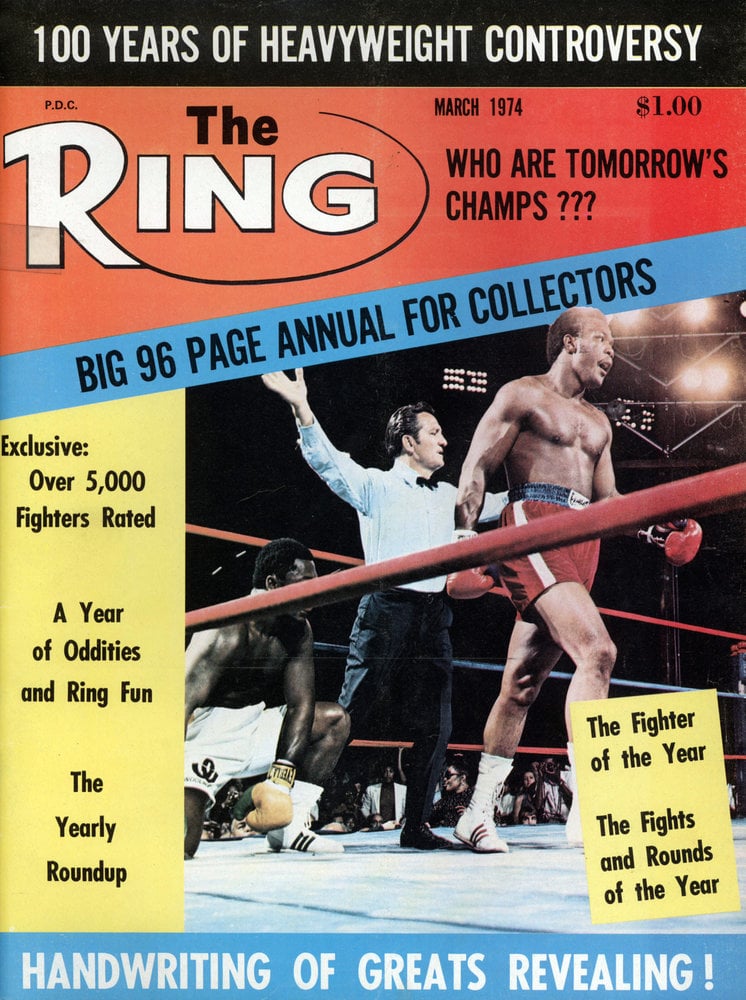

The first feature of an ongoing series celebrating the greatest rounds in boxing history begins with George Foreman’s unforgettable heavyweight title winning demolition of Joe Frazier. Round 2 of this clash of undefeated punchers was The Ring’s 1973 Round of the Year.

Muhammad Ali’s star shone so brightly throughout the 1970s that it is easy to squint and blur the rest. And when other figures from that golden age in heavyweight boxing do come into focus, it is invariably on account of their orbit having brought them into close proximity with the GOAT rather than an acknowledgement of any standalone greatness.

Despite their caliber, this is, to some extent, understandable for men like Jimmy Young, Jimmy Ellis, Jerry Quarry, Ron Lyle and Earnie Shavers. Although undoubtedly good enough to be champions in any other era, none of the five ever strapped a world title around their waist and the show-me-your-medals mentality prevalent within professional sports means runners-up are rarely recalled without reference to the victor.

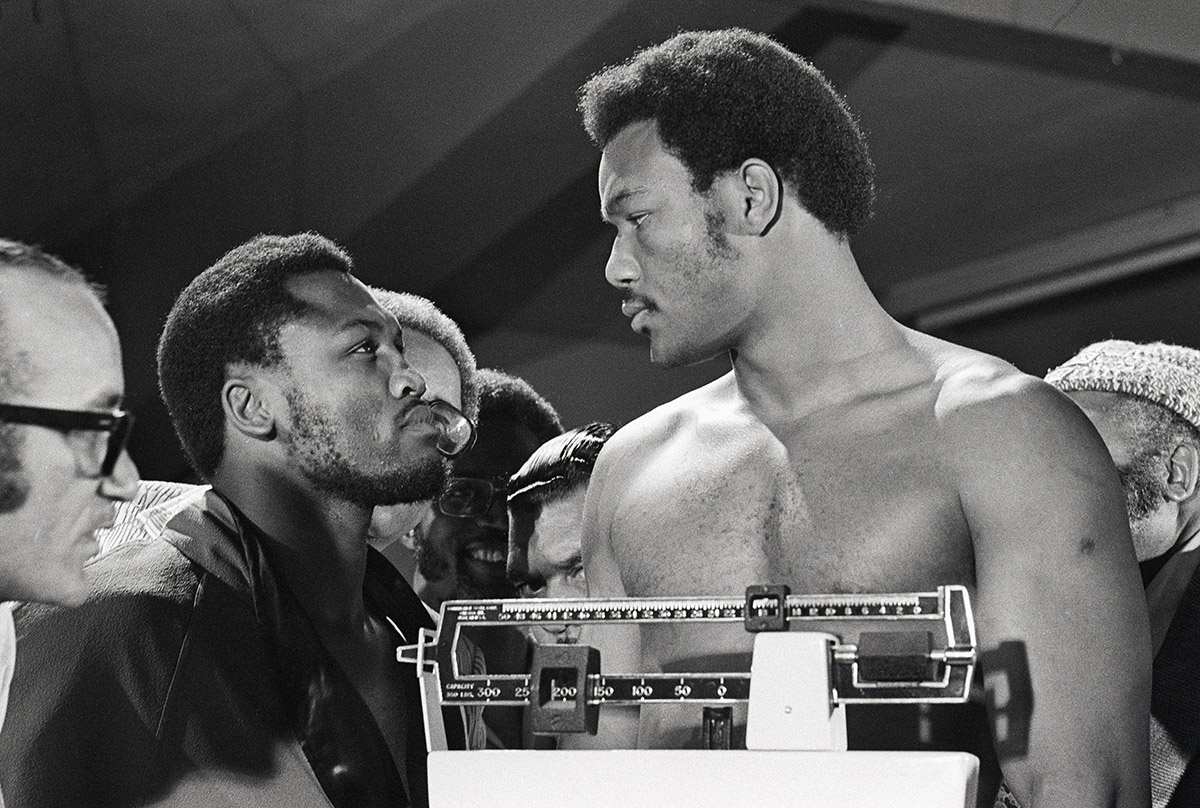

Challenger and champ did their part to promote the fight at a press conference in New York on December 12, 1972.

An even more striking measure of Ali’s aura is his impact on the legacies of two fighters who actually did reach the summit in their own right. Joe Frazier and George Foreman deservedly make the top 10 of any list of the greatest heavyweights of all time, yet even they struggle to make much noise without Ali at least providing backing vocals.

Against a background of the now quasi-mythical, and genuinely extraordinary, events in which they played a considerable part in Kinshasa and Manila, Joe and George’s battles with each other tend to fade into obscurity in the minds of most casual fight fans. Falling a year before the Rumble and a year after the Thrilla, it’s as if their two bouts are merely the bread of a sandwich in which the Louisville Lip constitutes the majority of the filling. But if anything from those two fights is remembered, it is almost certainly the clubbing brutality of the second round of their first meeting in 1973.

In 1970, Smokin’ Joe beat Jimmy Ellis in Madison Square Garden to become the heavyweight champion of the world. His hard head, relentless bob-and-weave style and a left hook from hell then helped him defend it for three years, including a clear and unanimous decision over Ali in 1971.

Foreman had been cutting a belligerent swathe through the division during that time. He racked up 37 victories in just three years, most of which were early knockouts with little fuss. With the pedigree of an Olympic Gold medal from the 1968 Games in Mexico behind him, the young wrecking machine warranted his shot at the champ, regardless of Ali’s or Don King’s protests to the contrary.

To hear the affable, God-fearing grill salesman speak today, it is difficult to appreciate how menacing a figure he was back in the early ’70s. If modern-day loveable George and back-in-the-day killer George are difficult to reconcile, it may be because the nasty, threatening streak in Foreman was a little more contrived than in other great intimidators such as Liston or Tyson. In fact, it was after sparring with Sonny in 1968 that Big George decided to exaggerate his dark side to cultivate a more imposing boxing persona. A 6-foot-4 frame and frightening punching power did the rest.

Regardless, reputations were neither here nor there to a man like Joe Frazier, and he climbed into the ring a confident 3-to-1 favorite to retain his title. The gambling consensus was that he’d be simply too tough, too fearless and too experienced for Foreman and he would knock the Texan out long before the final bell.

Frazier was a fearless favorite going into the fight despite Foreman’s imposing stature.

In a forerunner of the impoverished-nation-sponsors-title-fight template that Don King would exploit to perfection in Zaire and the Philippines, the ring in question was situated in the National Stadium of Kingston, Jamaica. The location demanded a tropically flavored sobriquet for the bout, and the promoters duly obliged with The Sunshine Showdown. In truth, by the time Joe and George stood face to face in front of 36,000 fans on the 22nd of January 1973, the sun had long since turned in for the night. But if we define showdown as a decisive confrontation, then at least one half of the fight’s moniker was entirely apt.

Contrary to the battle-worn memories of most old-time warriors, Foreman exudes easygoing self-deprecation when he recounts his exploits in the ring. Consequently, his version of events should often be consumed with a pinch of salt to counteract the effects of George genially downplaying his own achievements. Forty years after the event, Foreman spoke of being afraid entering the ring that night. That he presumed Frazier was bigger and stronger than him. That he worried knocking the champion down would simply lead to incurring more wrath and pain than a non-embarrassed Frazier would otherwise deliver. Who knows, perhaps he really did feel that way. But if so, there is no evidence of it whatsoever in the four-and-a-half minutes the fight lasted.

Frazier’s style of bobbing and burrowing and boring into close quarters was tailor-made for a taller man throwing uppercuts with bad intentions.

As they listened to the referee’s instructions in the center of the ring, any delusions Foreman had over Frazier’s size must surely have been dispelled. The younger man was a full four inches taller and he looked it, and then some. Frazier swayed from side to side in the staredown, but Foreman remained steady, his large, round face glistening with sweat and petroleum jelly and his small, dark, piercing eyes fixed intently on his prey. Small pockets of puffy flesh sat swollen beneath those peepers. Today they have descended and merged into the type of high, fulsome cheeks that billow and demand a grandma’s pinch with every smile. Back then they looked more like mini airbags, inflated and ready to absorb the blows that came their way.

And in the opening 30 seconds, two or three trademark left hooks from the champion did catch the challenger’s attention. But Frazier then took a wrong turn and found himself hurtling down a one-way street against a flow of traffic dominated by heavy articulated 18-wheelers. Back then, heavyweights still wore eight-ounce gloves, and when one of the most devastating punchers in the history of boxing slipped a pair on and began bludgeoning your head with both hands, you knew all about it. Or rather, you didn’t.

Before the fight, the legendary Howard Cossell, another man synonymous with Ali, described the ring canvas as: “Like a mattress, very soft, a Joe Frazier kind of canvas.” Little did he know how prophetic the images he conjured of a tired Frazier lying on a padded ring floor would be.

Before the fight, the legendary Howard Cossell, another man synonymous with Ali, described the ring canvas as: “Like a mattress, very soft, a Joe Frazier kind of canvas.” Little did he know how prophetic the images he conjured of a tired Frazier lying on a padded ring floor would be.

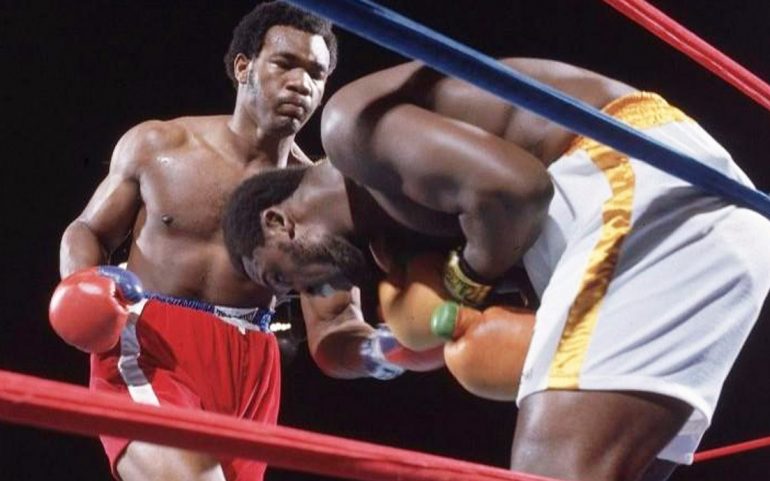

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but Frazier’s style of bobbing and burrowing and boring into close quarters was tailor-made for a taller man throwing uppercuts with bad intentions. Three times in the opening three minutes, Foreman decked his opponent. The first knockdown was from a short right uppercut off the back of a captive-bolt-pistol left jab. The shock gave birth to Cossell’s now legendary “Down goes Frey-sha! Down goes Frey-sha! Down goes Frey-sha!” commentary.

The second was from a more devastating right uppercut that followed a barrage of everything from a boxer’s worst nightmares. Yet another right uppercut did the damage for the third fall as Frazier collapsed backwards right on the bell. Referee Arthur Mercante Sr. took up a mandatory eight count but gave up, as the visibly shaken champ was already being helped onto his stool by his team. The three-knockdown rule had been waived, but it would have made for an interesting decision otherwise.

The second round was a brutal formality. Only the referee belatedly warning Foreman for his blatant two-fisted shoves delayed the now-inevitable. That intervention was enough to send Foreman’s trainer, Dick Sadler, scampering along the ring apron in exasperation, but Big George was unperturbed. When waved back in, he reversed Joe into the corner in which Sadler was hunkered, planted his feet and set about the champion with a controlled fury in which every punch was thrown to be the last.

At one point, a devastating left hook connected with the side of Frazier’s head and the impact caused his right knee to buckle and almost give way underneath him. His body righted itself to avoid a fall, but by now his brain was no longer in complete control of his movements. Taking advantage of the momentary lapse in defense, Foreman landed another huge right hand that this time caused both knees to buckle simultaneously. In a final, frantic attempt to maneuver their host to safety, Frazier’s scrambled neurons sent out one more electrical surge that propelled Joe towards the neutral corner, hopping for cover. Foreman didn’t even let him get that far, and a clubbing overhand right caught the champion on the back of the head and sent him down for a fourth time. The Third Geneva Convention outlaws attacking retreating and defenseless adversaries, but Big George was obviously not a signatory to that particular treaty.

Neither was he the cold-hearted executioner his murderous image portrayed. As Mercante ushered Foreman to a neutral corner, he can clearly be seen looking towards Frazier’s trainer, Yancey Durham. A ringside reporter later said that Foreman told Durham to “stop it or I’m going to kill him.” Durham didn’t stop it, and barely 15 seconds later, the scene was repeated. A delayed reaction to a left uppercut that Frazier took square on the chin caused him to go down almost comically as he swung a subsequent hook of his own. Again, George looked immediately and pleadingly at Joe’s corner. Again, the massacre was allowed to continue.

Frazier wasn’t able to avoid Foreman’s power for long.

If any defense can be offered for Durham and Mercante, it is that Frazier was now jumping up relatively quickly from each knockdown and easily beating the referee’s count. On the other hand, when the inevitable is a series of unanswered concussive blows, why delay it?

The final fusillade was perhaps the most ferocious of all. It was nothing more than target practice on a heavy bag with arms. With the champion backed onto the ropes and ducking and diving to no avail whatsoever, Foreman battered Frazier until all his weight was shifted onto his left leg. One almighty cuffing right then sent Joe soaring through the warm Jamaican air in the opposite direction. Pause the footage and you can actually see the 214-pound heavyweight champion of the world in mid-air, literally knocked clean off his feet.

Joe, being Joe, stood up immediately and looked to fight on, albeit on shaky legs. George, being who we now know George to be, had to be literally dragged away from Frazier’s corner as he beseeched Durham to end the slaughter. Ali’s trainer, the great Angelo Dundee, was at ringside doing likewise to the referee. For an awful moment it looked like Foreman would be forced to continue and render Frazier fully unconscious, but with Durham now standing on the ring apron, white towel in hand, Mercante finally stopped the fight at one minute and thirty-five seconds of the second round.

The two fighters were soon sharing a quiet word in the beaten man’s corner. They became genuine friends, and that happy fact diminished the intensity of their rematch in 1976, in which Foreman again stopped Frazier, this time in the fifth.

The 50th anniversary of the fight has just passed. Five full decades, and still boxing waits for two more of their kind to grace the ring together and remind us how special the heavyweight division can be.