Chronicling the Cruelest Sport

AN INTERVIEW WITH CARLOS ACEVEDO

By Kyle Sarofeen, co-founder of Hamilcar Publications

Carlos Acevedo’s book of essays, Sporting Blood: Tales from the Dark Side of Boxing, quickly entered boxing’s literary canon when it was published in 2020. A new expanded edition of that book is now available, fresh off the April 2022 publication of Avecedo’s second book, The Duke: The Life and Lies of Tommy Morrison, which is a moving, horrifying, droll and ultimately tragic account of the Oklahoma heavyweight’s stranger-than-fiction life. In this interview Acevedo discusses both books, his authorial approach, some of the chicanery in boxing and more.

Kyle Sarofeen: So a new expanded version of your book Sporting Blood is out? What’s in the new edition?

Kyle Sarofeen: So a new expanded version of your book Sporting Blood is out? What’s in the new edition?

Carlos Acevedo: Yes, a new edition came out a couple of months ago. Sporting Blood has done well, which is both gratifying and surprising because I have a pretty low profile, especially over the last couple of years. Anyway, this expanded edition has two new long stories, both about larger-than-life figures who were in their twenties when they were murdered.

KS: The new stories are about Battling Siki and Stanley Ketchel. What did you find compelling about them?

CA: Battling Siki and Stanley Ketchel were permanent headlines during their careers and, later, they became sad examples about the connection between boxing and destruction. Siki, in particular, was someone who was chewed up by the sleazy demimonde of boxing – the crooked managers, the corrupt ruling bodies (such as they were at the time), the mob element. He was also poorly served by sportswriters, who portrayed him in the most appalling, racist terms imaginable. Because so much written about Siki is fiction, most of what continues to circulate about him is dubious. Thankfully, Peter Benson wrote a definitive account that I drew from: Battling Siki: A Tale of Ring Fixes, Race, and Murder in the 1920s.

Ketchel was a live wire with a background possibly concocted by his management team (specifically the cowboy element). But he was a hellraiser, all the same. Being white allowed him to get adulatory coverage that also seemed fictitious at times. His death, at 23, when he was still middleweight champion of the world, is one of the most shocking of all the dark tales in Sporting Blood.

KS: And speaking of compelling subjects, what drew you to Tommy Morrison, the subject of your last book, The Duke?

CA: What drew me to Tommy Morrison was the operatic nature of his life, which made for plenty of strange, compelling stories, and also the theme of the American dream gone off the rails. But the other part that interested me was the way his career reflected the seamy underbelly of boxing in the early 1990s. At its top levels, boxing is inhospitable to the truth; away from the big money and the glitz, you can forget about anything even resembling reality. So, The Duke is an attempt to make sense of that dishonest world, but its structure is also informed by the fact that the truth is marred by it. The fraud, the lies, the pratfalls in the ring, the tackiness, the pandemonium. The Duke is also something of an overview of the heavyweight division in the early 1990s, which was a chaotic time, and it was fun to write about all the madness that took place. And Morrison was a big part of that.

KS: Some people have taken issue with the relative lack of interviews in The Duke. Can you speak to that?

KS: Some people have taken issue with the relative lack of interviews in The Duke. Can you speak to that?

CA: Not many were interested in talking to me. Which is just as well, because interviewing people for The Duke meant talking to killers, rapists, bigamists, conspiracy theorists, phony lawyers, convicted felons, meth heads, underground surgeons and garden-variety boxing participants who are by nature untrustworthy. They would all be, to one degree or another, I think, unreliable narrators. So when some of them declined to participate in The Duke or when they blocked me on Facebook, I went to the archives instead. Luckily, there were thousands of pages of available court records to sift through, and since Morrison was someone who loved publicity, there was plenty of material about him.

KS: Since there was so much material out there about Morrison, what was your approach when it came to actually writing The Duke?

CA: As a writer, I’m primarily interested in selectivity and authorial control. Choosing what goes in a book is important, but so is choosing what to leave out. That’s why The Duke has only two parts and also why it’s written in fragments: to emphasize the most important aspects of the narrative. I wanted to have a lean and focused narrative, one with a sort of propulsive feel to it. You’re just swept along, hurtling toward the inexorable, like Morrison himself, in some ways. Boxing books, in general, are too long and meandering. The Duke could have been 350 pages, 400 pages, especially if I was one of these writers who specializes in what William Gass called the uselessly precise detail.

KS: You’ve taken some heat from some “ardent” Morrison supporters since the book came out. Did that surprise you?

CA: Well, I was aware of the crackpot nature of his following, many of whom probably believe that JFK Jr. is alive and are looking forward to hanging out with them at a Golden Corral. You can find some of these folks in the comments section of Morrison YouTube videos, talking about the great conspiracy to keep Morrison away from Mike Tyson and how all of Western Civilization combined forces to derail him with a false HIV diagnosis. These people are overmatched by reality, but, unfortunately, the Tommy Morrison orbit is full of these types.

KS: Some of them have characterized The Duke as being a hit piece. What’s your response to that?

CA: How do you write a hit piece of a man who once slashed a woman with a broken bottle, who physically assaulted two of his wives, who was arrested almost as many times as he had fights, who spent time in prison for a variety of offenses, who injured a girl in a drunk-driving incident, who made racist and homophobic comments publicly, who jabbed his mistress with a hypodermic needle before marrying her in a bigamous union? And none of what I just said is a value judgment or sanctimony. I was raised in a dangerous Bronx neighborhood where malfeasance of some sort of another took place regularly, and the moral skies were always at least partly cloudy. I knew ex-cons and serious drug addicts. My high school friends snorted coke, smoked PCP, drank Colt 45 and carried copies of The Satanic Bible in their knapsacks.

The Duke was on top of the world after the Foreman win in Vegas. (Photo by Bernstein Associates/Getty Images)

There is editorializing in The Duke; it is impossible, even for the most objective, impartial writer to suppress commenting, so to speak. But part of writing is interpretation, and to write dry, neutral prose about bizarre, sometimes grievous behavior just seems odd and essentially like a copout to me. Did Morrison belong in a supermax? Was he the Green River Killer or Timothy McVeigh? No, of course not, but the facts as they exist in the record are the facts and I try not to be condemnatory – at least not all the time.

KS: With respect to Morrison’s in-ring performance, some will point out that his record was 48-3-1 with 42 knockouts, which, they’ll argue, is a pretty good record. What do you say to that?

CA: Every boxing fan, from the casual to the dedicated, insists boxing is corrupt. This is something all boxing observers agree on. Right? Boxing is a sleazy, crooked, gutter sport. The sanctioning bodies are corrupt, the judges are corrupt, the promoters are corrupt, the referees are corrupt, the timekeepers are corrupt – whatever. But when they actually see corruption, first they have to figure out whether or not they happen to be a fan of the fighter or promoter involved. And that’s also part of boxing: provisional morality. Fights against opponents pulled from the crowd or against opponents who are hiding from police warrants are essentially consumer fraud – another form of corruption.

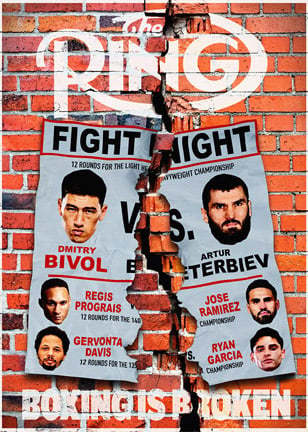

March 1992 issue

My criticism of Morrison’s quality of opposition is not revisionist history. This aspect of his career was front-and-center while he was a pro. The press trashed Morrison for his opposition. His own matchmaker quit because of the opponents. Peyton Sher, longtime promoter and matchmaker in the Midwest, thought Morrison’s opponents were awful, so he left. Las Vegas, the gambling capital of the world, refused to post odds on a bunch of his fights. In New Jersey, the Athletic Commission once rejected seven consecutive proposed matchups involving Morrison before they finally approved a fight.

Tommy Morrison was matched to fight his fictional opponent from the Rocky movie! And when Mike Williams fled the locker room before the fight, the promoters pulled a guy nicknamed “Doughboy” out of the crowd to replace him. Tim Tomashek, aka Doughboy, was in the crowd drinking beer that night! Hopefully, it was a light beer, Coors or Rheingold or something. I mean, these shenanigans are like scenes from the Great White Hype or Play It to the Bone. It’s true Doughboy had been brought in as a last-minute substitute, but he was completely unfit to challenge for a piece of the supposed heavyweight title.

Boxing is full of hero-worshiping narratives, and that to me is an extension of the industry itself, where the managers lie to you, the promoters lie to you, the fighters lie to you, the ringside commentators lie to you, the publicists lie to you – nonstop. It’s similar to pro wrestling from the pre-1980s. Before the WWE became this global billion-dollar corporate business, it was a very seedy subculture modeled on carnival traditions, barnstorming and con artistry. And the audience, before they began to wink along with the show in a kind of meta way, were known as marks, basically the same thing as suckers or saps, and the wrestlers despised them. Boxing is still in that mark phase, where gullible fans are fed stage-managed events without seeing them for what they are.

KS: What can we look forward to from you in the future?

CA: Right now, I’m working on two books simultaneously, not one of my smartest ideas. Neither of them are about boxing, which is a relief after writing about it for 15 years. One of the new titles is about film and the other is a true crime book, which will probably be less sleazy than the Tommy Morrison story. I’m just kidding about that.

Sporting Blood: Tales from the Dark Side of Boxing, Expanded Edition and The Duke: The Life and Lies of Tommy Morrison are both available from Hamilcar Publications wherever books are sold.