John Scully (left) with former middleweight titleholder Gerald McClellan in 2019.

FORMER CONTENDER JOHN SCULLY’S LIFELONG LOVE AFFAIR WITH BOXING INCLUDES A ONE-MAN CHARITABLE CRUSADE TO HELP FIGHTERS WHO ARE STRUGGLING WITH THE EFFECTS OF THEIR TRADE

The whole thing got started because of overcrowding, to be honest about it. Overcrowding and a realization in the mind of former super middleweight and light heavyweight contender John Scully that they call boxing the hurt business for a reason and the truth of that harsh reality is some fighters get hurt in ways that can’t be fixed.

Scully was once a nationally ranked amateur who just missed a shot at the 1988 Olympic Games when he won a bronze medal at the Olympic Trials. As a professional, he fought for two world titles and survived 49 professional fights before retiring in 2001 to life as a trainer of young kids who will be saved by boxing as well as professionals with hopes and dreams like the ones Scully carried for so long.

Unlike many fighters he’d come to know and respect, Scully left boxing with a blessing, not a belt. He left with his mind clear and his body still functioning so well that he has sparred nearly every week of his life since retirement with the young amateurs and professionals he trains. What that led to was deciding one day he could help out a guy he never really knew beyond his reputation while also getting his house decluttered.

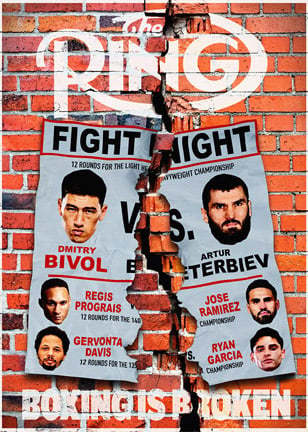

“About eight years ago, I started organizing reunions for fighters I’d remained in touch with,” Scully recalled recently while preparing to join light heavyweight titleholder Artur Beterbiev in camp, where Scully serves as his assistant trainer. “I just thought it would be amazing to get guys together in New York or Las Vegas or L.A., so I organized a few. That’s when it struck me that some of these guys weren’t doing as well as I thought.

“I’d heard about Gerald McClellan’s situation and I felt maybe I could sell some memorabilia that was taking up too much space in my house and give him some money. I put some stuff on eBay, and in five minutes I’d sold it. I was amazed. I sent the money to Gerald’s sister and realized it would be so easy to reach out to a lot of guys I knew, like Roy Jones, James Toney, Vinny Paz, and get them to sign things to raise money. It would be crazy not to do it.”

Read “Best I Faced: John ‘Iceman’ Scully”

So began a one-man crusade to help men for whom boxing became a cruel mistress. Scully collects signed belts, gloves and other memorabilia where he can find it, sells it and regularly sends checks to help bedridden Wilfred Benitez, the three-division world champion and hall of famer who has long suffered from degenerative brain problems; Prichard Colon, who in 2015 sustained a brain injury during a fight that left him in a coma for 221 days and with staggering long-term injuries; and McClellan, the two-time middleweight champion who also suffered a debilitating brain bleed in his final fight, which left him unable to see or walk without assistance and with other extensive health problems requiring 24-hour care.

“I didn’t want to let my boxing connections go to waste,” Scully said. “I used to watch Benitez when I was a kid and tried to imitate him, going to the ropes and trying to make guys miss 50 times.

Scully at Wilfred Benitez’s bedside in his Chicago home, 2018.

“I sat with Wilfred once in his living room in Puerto Rico. He was in a hospital bed and I was in a chair next to him. I don’t think he had any idea who I was, but he held my hand for almost two hours. His sister told me he knew I was a boxer, so he felt close to me. A great champion like that, holding my hand to keep a connection to the sport that did that to him was amazing.

“I visited him twice, in Puerto Rico and Chicago, where he lives now. Seeing what his sister has to sacrifice to care for him was humbling. To help if I can is an honor.”

Scully’s connection with McClellan ran a bit deeper. Both were amateurs around the same time and although they never fought, they knew each other in the way talent knows talent. Scully once ran into McClellan in a gym in Las Vegas in 1988, not long after Scully had lost in the Nationals final. McClellan gave him the ultimate compliment that day.

“He told me I got robbed,” Scully recalled with a laugh. “I always felt because we were at some big amateur tournaments together that we had a kinship even though we weren’t friends then.”

Almost 30 years later, their paths crossed again in 2014 in New York. What Scully saw was an unneeded reminder of the danger prizefighters face. For all its personal glory and thrilling moments, boxing is a sport that can make a man disappear, leaving him unable to share the old stories and memories Scully loves, because they are locked in a permanently dark limbo where memory fades and the damage they suffered is beyond repair.

“The thing is, it’s not just the fighter who suffers,” Scully said. “Gerald’s sister Lisa tends to him 24 hours a day. Wilfred’s sister pretty much does the same. Their lives are on hold too.”

Scully had no connection with Colon beyond the fact they had been at times working in the same gym in Florida and Scully was at the 2015 fight where Colon was permanently injured. It was not something a man forgets.

Scully with former lightweight contender Pito Cardona, who, Scully says, “makes no secret of the fact that he is disabled due to the effects of boxing.”

“I understand people getting hurt is part of the game,” Scully said. “I’m around older fighters all the time. I hear the pain and confusion in their voices on the phone. I see guys who can hardly walk today who were once great fighters. It’s part of the game. I can’t pretend it isn’t.

“I’ve been there live three or four times when a guy died or was permanently injured. Some people get hurt and recover fine. Others don’t come back right. People see fighters when they’re at their best. They don’t see the aftermath. I do, so I help if I can.

“It started slowly, just helping when I had something to sell. But it’s really picked up the last couple years. People are catching on and sending me stuff.”

Like everything in boxing, Scully’s solitary charitable acts have led to skepticism from some corners. He’s asked some fighters for a signed glove or other help only to have them question if the money was going where he said it is going. His response is as simple and direct as a hard jab to the face.

“People see fighters when they’re at their best. They don’t see the aftermath. I do, so I help if I can.”

“I asked one fighter to sign a couple drawings to raise money for Wilfred,” Scully recalled. “When he seemed skeptical, I gave him Wilfred’s sister’s number. Anyone who questions what I’m doing can call them themselves. Every cent I raise, I send.”

Some friends of Scully have begun talking about forming a 501(c)(3), a Federally recognized non-profit that can raise money for charitable use without being taxed. If that happens, Scully’s long-term plan is to run an annual fundraising dinner that would turn his love of reuniting with former fighters into a way of helping more of those from whom boxing extracted a devastating toll.

Initially, Scully figured he’d help a few guys, but once what he was doing became public, he received a call from a fighter he barely knew asking for help. He put up a signed glove on eBay. It sold for $500. He’s been doing things like that ever since.

“When I gave the money to him, he was blown away,” Scully said. “In the beginning I thought it would be just Gerald and Wilfred, but it just kind of snowballed.

“I’ve had some people criticize me for using the names of Wilfred or Gerald, and I tell them, ‘People don’t just send money for some phantom fighter.’ I’ve only put out the names of three guys, but there have been others I helped. I don’t mention their names. No need. Just help them.”

Standing in front of a mural depicting Willie Pep vs. Sandy Saddler in Hartford. Left to right: Scully, “Irish” Micky Ward and two-time welterweight titleholder Marlon Starling.

Despite what he knows about the price some fighters pay, for John Scully boxing remains his life’s work. He began it the way most do, as a kid with a head full of dreams in a hotel room where his father stayed when he would come to visit his son in Hartford.

“We’d watch the fights on television,” Scully recalled. “He’d be in a chair and I’d be on the bed, wrapping my hands with toilet paper and putting on gloves he gave me.

“I’d throw water on my face and ‘fight’ 15 rounds against Jimmy Ellis or whoever was on TV. I’d score the fight, then go in the bathroom and announce the winner like [Hall of Fame announcer] Chuck Hull did.

“The joke between us was my Dad got tired of me fighting guys on TV, so he took me to a gym in Windsor when I was 14. My mother was scared of it but she never tried to stop me. She knew I loved it.”

Scully loved it enough to give up high school football after injuring his shoulder in a game just before the 1983 Golden Gloves tournament. He knew a choice had to be made. His choice became his life’s work.

Today, Scully trains amateurs at the Charter Oaks Boxing Academy not far from where he started out. He also works with Beterbiev and along the way has trained four standouts: Ring/WBC light heavyweight champion Chad Dawson, WBA junior middleweight titleholder Jose Rivera, junior featherweight contender Mike Oliver and lightweight contender Liz Mueller. Size, age and skill level mean little to Scully. His love of fighters is universal.

“When I was an amateur in Hartford, I started sparring with younger kids,” Scully explained. “I began training amateurs when I was still fighting. December 8, 1995, I was in a suite at Foxwoods and fighting a main event against Michael Nunn. Three weeks later, I was sleeping on the floor of a $49 hotel room at a Junior Olympics regional tournament in Lake Placid with kids I trained. That’s boxing. Training fighters was a natural progression.

“When I was an amateur, I learned things from an old Hartford trainer named Johnny Duke. When he died, people from all over came to tell stories about things he’d taught them. Things they remembered decades later. Right then I understood you could have a positive effect on a kid through boxing. I wanted to try and do that.”

Scully with current unified light heavyweight titleholder Artur Beterbiev in camp.

John Scully’s life has been circumscribed by a boxing ring. Despite its dangers, it is a love affair that has gone on for over 40 years. It has taken him around the world and brought him back to a place where he hopes some of his peers will join him. A place where helping fallen fighters is the only goal.

“Nobody is obligated to do anything,” Scully said. “I understand that. But sometimes I wonder why more of the big names in the sport aren’t doing something similar. They know the damage fighters suffer. They know the need.

“No one has to do anything. I’m not saying they do. But there are people who got a lot out of boxing. Floyd Mayweather doesn’t owe anybody anything, but think what he could do for Wilfred, Prichard and Gerald. He could do it with money he wouldn’t even notice was gone. There are plenty of other guys too. I’ve never heard from a single promoter.

“Jake Paul wants to be seen as legitimate in the boxing world. He wants to be accepted and hasn’t been, even though he’s making millions. He could do a lot with the money he’s made from our sport. He could put $1 million in a mutual fund for ex-fighters. He wouldn’t even miss it, but it would make a lot of ex-fighters’ lives easier. If you have the wherewithal, why would you not do it? I don’t know the answer to that. Maybe some guys don’t want to be involved because they don’t want to be reminded of how lucky they were.

“I didn’t become a world champion, but I did better than a lot of people and at 55 I’m still in the gym with young kids with the same dreams I had. If I can help them, I do. That’s why I hope this 501(c)(3) gets done. If it doesn’t, I’ll just keep doing what I’ve been doing. Helping the best I can.”

John Scully can be contacted at [email protected].