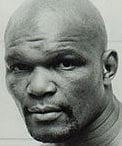

A piece of Philadelphia boxing history dies with Briscoe

A piece of Philadelphia boxing disappeared for good last week when Bennie Briscoe died in a hospice at 67 years old. “Bad Bennie” was the most successful and most beloved of the crop of skilled, hard-nosed, Philadelphia middleweights of the 1960s and ’70s that included Eugene “Cyclone” Hart, Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts, Willie “the Worm” Monroe, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward and others lost to history and the record books but not to the memories of those who saw them take care of business at the Spectrum, the Arena, Convention Hall, or the Blue Horizon.

Briscoe never won the world title — for most of his career there was but one to get at 160 pounds, if you can imagine — but of all those wonderful fighters, he came the closest, losing a 15-round decision to the great Carlos Monzon in Buenos Aries in 1972 and another to Rodrigo Valdes in Lombardia, Italy in November 1977.

Valdes also knocked out Briscoe in Monte Carlo in 1974, the only time Briscoe was stopped in a 96-fight career that spanned 20 years. For Briscoe, getting big fights was not easy.

“It took Bennie a long time to get the high-profile fights,” J Russell Peltz, who promoted Briscoe from 1970 to ’79, told Ring TV.com. “He went up the ladder by just grinding guys down over a long period of time.”

That he did. Briscoe fought everyone there was to fight at 160 pounds, including Emile Griffith, Luis Rodriguez, Vito Antuofermo, Marvin Hagler, Tony Mundine, Georgie Benton (who later trained him), a young Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, and, of course, Hart and Hayward.

Some of those fights he lost, especially later in his career. He won many more while compiling a career record of 66-24-5 (53 knockouts), and just as often it seemed he did well enough to win but watched the other guy walk away with the judges’ decision. He was one of those guys who didn’t often get the benefit of the doubt, but it didn’t stop him from fighting everyone. He was fearless.

Peltz said that as he told attendees at Briscoe’s retirement party in 1983, “There was a Bennie Briscoe in every town in the country, somebody that nobody wanted to fight. And Bennie fought all those guys, all those tough black guys that nobody would fight.”

Mustafa Muhammad, who won the WBA light heavyweight title in 1980, lost a split decision to Briscoe in Philadelphia in 1975 and though 35 years later he maintains he deserved the win (you can watch the fight in three parts beginning here), he gives Briscoe his due.

“I thought I outboxed him and won easy, but it is what it is,” Muhammad said. “We stood toe-to-toe and gave the Philly fans what they wanted. It was a good fight. I respected Bennie and always will. When you fight Bennie Briscoe you gotta bring your A-game. You can’t come in half-steppin’ and stuff like that. You gotta come right.

“He was a competitor and a credit to boxing,” Muhammad continued. “And a credit to Philadelphia. When you say Philadelphia you right away think of Bennie Briscoe. No nonsense, blue-collar worker. Bennie was the greatest fighter to never win a world title. You gotta take your hat off to him because he fought everybody and not just in Philadelphia. He went around the world.”

Rob Murray, trainer and manager of heavyweight contender Eddie Chambers, has been part of the Philadelphia boxing scene for decades and remembers Briscoe from his early days as an amateur.

“Bennie is probably the last of the real, original throwback fighters who could have fought in any era,” Murray told RingTV.com. “Bennie could have fought bare knuckle. He was that kind of fighter. Very journeyman, nuts and bolts, tough, go-all-the-way type guy.”

Murray said Briscoe was not above bending the rules when it was required. Indeed, this is one of the characteristics that endeared him to Philadelphia fight fans. He was no angel in the ring.

“I remember his fight with Rafael Gutierrez at the Spectrum (in 1971),” Murray said. “Gutierrez hurt Bennie bad in the first round. Bennie was wobbling all over the ring. Gutierrez went to finish him and Bennie hit him real low, and hard. Gutierrez went right down. And in the next round Bennie knocked him out.”

It wasn’t only Briscoe’s ring demeanor and fearlessness that made him a fan favorite. No matter how big he got, he was just another one of the guys from the neighborhood. Even when he was fighting the best fighters in the world he worked for the City of Philadelphia in trash disposal. He did that for 40 years.

“Bennie was one of the guys. He would hang out on the street corner at Broad & Girard with all the pimps and all the drug dealers and all the transvestites and then at the end of the day he’d go to the gym,” Peltz said.

“He never got caught up in all that because he took such good care of his body. But they were all friendly with him. He’d come to me before the fights and ask for $500 worth of tickets to give out and I’d say, ‘What are you doing?’ He’d say, ‘Yeah, they’re my friends, I gotta give them tickets to the fight.’ I said, ‘If they’re your friends they should be buying tickets!'”

Peltz said Briscoe’s strength, durability and toughness made him special. And with him it was never an act. There was no false bravado. Just fighter.

“I always say he was a trash man who didn’t talk trash. And he wasn’t a put-on guy like James Toney, he was a real bad-ass but he was a pussy cat unless you pissed him off,” Peltz said.

Murray agreed, recalling that although Briscoe fought throughout his career with a Star of David on his trunks, in Murray’s view he probably didn’t even know what the symbol stood for; he simply wore it as a personal favor to Jimmy Iselin and Arnold Weiss, his Jewish managers. Murray also said that much of the purse money Briscoe made he sent to his mother in Georgia.

“All he ever talked about was wanting to build a house for his mother, who was still down in Georgia,” Murray said. “He talked about it all the time. And I think that eventually he did it.”

It’s an old story: a killer in the ring, a gentleman outside of it. But Benny Briscoe was no one’s old story. In a way he was the king of Philadelphia, or at least a prince, when Philadelphia was overflowing with fight game royalty. It’s trite, but they don’t make them like Bennie Briscoe anymore. Not even close.

“I’m buying tickets right now to go to the funeral,” Muhammad said toward the end of our conversation about Briscoe. I asked him why he would fly from Las Vegas, his home, all the way to Philadelphia for the funeral of a long-ago opponent.

“I have to. A guy like Bennie, you have to pay your respects,” Muhammad said.

Yes you do. We all do.

Some random observations from last week:

There’s a rumor suggesting that since he’s officially out of the running for a Pacquiao fight, Juan Manuel Marquez will meet Erik Morales, a match many will scorn. Not me. Marquez will win, but Morales has more in the tank than you think and will make it fun.

Plus, every other conceivable match that could have been made among what Max Kellerman correctly called a golden age of featherweights a while back has been made: Pacquiao-Barrera, Marquez-Barrera, Barrera-Morales, Pacquiao-Morales, and Pacquiao-Marquez. Marquez-Morales completes the circle, regardless of how old they are

Had a brief conversation with Leonard Ellerbe during which I tried to convince him that some kind of update from Floyd Mayweather about what he’s doing with his life is overdue. “Not right now,” Ellerbe told me very politely. If not now, when?ÔǪ

European lightweight champ John Murray just missed making this year’s Ring 100. The lightweight division is packed with aggressive, two-fisted bangers and Murray fits right in. Imagine the fireworks in a fight between he and Urbano AntillonÔǪ

Sergio Martinez-Miguel Cotto. Now there’s a fight. Too bad Cotto’s tied up with Ricardo Mayorga and then, presumably, Antonio MargaritoÔǪ

My column last week on the abomination that is Manny Pacquiao-Shane Mosley generated a lot of email and commentary along the lines of, if not Mosley, then who? At the risk of repeating myself, Juan Manuel Marquez, of course.

And in anticipation of the usual cries around Pacquiao being too big, I remind everyone of what I wrote in this space several weeks ago: Unlike every other non-heavyweight on the planet, Pacquiao struggles to keep his weight up — to the tune of 7,000 calories a day when in training, according to his fitness guy, Alex Ariza. He is a natural welterweight, or whatever he is, like Evander Holyfield is a natural heavyweight. He goes back to eating like a normal human, he and Marquez are the same size.

Bill Dettloff, THE RING magazine’s Senior Writer, is working on a biography of Ezzard Charles. Bill can be contacted at [email protected]