With Hall of Fame nod, Michael Moorer gets the respect that often eluded him

Michael Moorer doesn’t waste his time on what-ifs. It’s a pointless exercise because, as he puts it, “if it was meant to happen, then it would have happened.” There’s little use in pondering what would have happened had fights with Mike Tyson, Lennox Lewis or Riddick Bowe transpired, or if he had slipped his head out of the way of one more right hand from George Foreman, or if the top light heavyweights of his day had stepped into the ring with him.

It’s hard to argue with his logic.

After all, the three-time heavyweight champion and one-time light heavyweight champion is being inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2024 because of what he did accomplish, not what could have been.

“People tell me it’s long overdue. I personally don’t think so because at first, once I retired I never gave it any thought,” says Moorer (52-4-1, 40 knockouts) as he takes a call in his car near his home in South Florida.

“Now, as I learned about the Hall of Fame, and what it’s about, what it represents, I’m overjoyed knowing that I’m gonna be inducted in June. I’m happy, I’m ecstatic about it. It’s something that a lot boxers strive for. This solidifies everything, that I’m one of the best.”

For Moorer, 56, the upcoming induction – which takes place during the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s annual induction weekend from June 6-9 in Canastota, N.Y. – is an expression of respect which the understated Moorer didn’t always receive during his 20 years as a professional. Sometimes lost in the shuffle of one of the greatest eras in heavyweight boxing, Moorer’s accomplishments have aged well, earning him a reappraisal with the benefit of historic context.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y. and raised in the rust belt town of Monessen, Pa., Moorer rose to national prominence as an amateur, winning the 1986 U.S. National title at 156 pounds with a win over future pro contender Thomas Tate.

Moorer turned pro in 1988 as a light heavyweight under Emanuel Steward, beginning a streak of 26 straight wins by knockout while wearing the KRONK Gym’s classic gold and red trunks. One of those wins, a fifth round stoppage of Ramzi Hassan just nine months after turning pro, earned Moorer the inaugural WBO light heavyweight title. Moorer defended the belt nine times over the next two years, but opportunities against the bigger names of the division like Virgil Hill and Charles Williams never materialized.

“I always wanted to fight those guys. I don’t know if there were any negotiations between management teams but I’ve always wanted to fight the champions to become the undisputed light heavyweight champion. There was never anything in the works that I knew of,” said Moorer.

What was happening is that the 6’2” Moorer was beginning to fill out, which meant that making the light heavyweight limit of 175 pounds was becoming a challenge in itself. Moorer says he walked around at 206 pounds and would feel weakened by cutting down the weight, which impacted his performances.

“That would deplete me, and after 4-5 times I was killing my body. I told Emanuel I’m tired of losing weight, I don’t want to lose no more weight, I don’t want to fight cruiserweight, I’m going straight to heavyweight,” recalls Moorer.

“My body was starting to mature into being a man from a boy. Once I started putting on that weight, it was destined for me to be there.”

It didn’t take long for Moorer to show he had the fight in him to hang with the heavyweights.

In his third fight as a heavyweight, Moorer faced the 230-pound Alex Stewart in an HBO-televised card headlined by Pernell Whitaker’s undisputed lightweight championship defense over Poli Diaz. Moorer got started early, dropping Stewart twice in the first round, first with a right uppercut and secondly with a left cross which bent his neck awkwardly over the top rope. Moorer tasted Stewart’s power the following round, getting rocked by a pair of right hands in the final minute. Moorer recovered quickly, and re-discovered his right uppercut in the fourth to stop Stewart and stamp himself as a heavyweight title threat.

“I think that fight solidified me in the heavyweight division,” said Moorer.

“That was a big man. When we fought a lot of people thought he was gonna beat me because of what he did in his past. I was in that era where I was like, I ain’t letting this motherf–ker beat me. I’m the baddest boy, I’m the baddest motherf–ker now, so if we’re gonna fight, we’re gonna fight. I saw that I can hit him with my jab and he was flat-footed. When he was standing in front of me, I saw I could hit him with different shots. I saw that he was stationary so I knew that I could bring things coming up like uppercuts. From the outside seeing how good that was, it was like an uppercut jab that crushed him. That was a devastating knockout.”

Less than a year later, in May of 1992, Moorer got a chance to fight for the vacant WBO heavyweight title against Bert Cooper, a relatively smallish heavyweight who had given Evander Holyfield the scare of a lifetime a year prior, dropping him before Holyfield rallied back to stop him in the seventh.

Cooper also gave Moorer supporters plenty to hold their breath over, as both fighters were knocked down in the first round. Cooper dropped Moorer again in the third before Moorer finished him with a devastating combo in the fifth.

The first knockdown occurred just forty seconds into the first round. Moorer remembers exactly what went through his mind as he picked up the count.

“I was like oh shit, you gotta get up now, you gotta show you’re a champion,” said Moorer.

“Bert was a bad boy, and once he dropped me I was like oh shit, we gotta fight now. In my mind it was like, it’s fight time. Back in that day and age I was the type of guy, I was a rowdy, young, mean guy. I was ready to fight anybody. When he hit me like that, I was like oh this motherf–ker hit me like that? We’re fighting now and I just locked my system and we went to war.”

Perhaps learning from his time at 175 pounds, Moorer vacated the WBO title without defending it, as he sought to be ranked by other organizations for a chance to fight for the other belts held by the biggest names in the division. He finally got that chance in April of 1994, when he challenged Holyfield for the IBF and WBA heavyweight titles which Holyfield had just won back in a rematch against Bowe.

Moorer, now trained by Teddy Atlas, entered the fight as a 2-1 betting underdog. In round two he was dropped by a left hook from Holyfield, but, thanks in part to a style advantage from being one of the few southpaw heavyweights of note, and profane prodding from his chief second, Moorer rallied to defeat Holyfield by majority decision and win the belts.

“As I was fighting Evander, I noticed that I was hitting him with my jab because I was a southpaw and his eyes were getting puffy. He didn’t train properly for that fight so I was just eating him up with my jab, trying to blind him and trying to land the straight left hand,” remembered Moorer.

Becoming heavyweight champion by defeating a respected warrior helped quiet some of the criticism that Moorer faced as a smaller heavyweight maneuvering his way among giants.

“As a light heavyweight, I got the respect there. I didn’t gain the respect in the heavyweight division as a contender until I fought somebody of significance. I think that was the only time when people knew that Michael Moorer is back, he’s a person to be reckoned with,” said Moorer.

As a heavyweight champion, there was no fight available that was more lucrative than Foreman, who, at age 45 and inactive for more than 17 months, seemed like a safe bet for the $7 million purse Moorer reportedly earned for the fight. Though Moorer was a 3-1 betting favorite, it was the gregarious Foreman who had the fans behind him at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

For the first nine rounds, Moorer fought one of the most complete performances of his career, picking Foreman apart with his jab and bouncing left hands off his stationary head. Trailing by five points on two cards and one point on the third, Foreman needed a Hail Mary to pull off the win. With one right hand, Foreman’s prayer was answered as he put Moorer down for the ten count, becoming the oldest heavyweight champion in history, twenty years after he had lost the title to Muhammad Ali in Zaire.

For better or worse, Moorer became part of one of the most memorable moments in boxing history that night.

“People bring it up, I forgot about it. It’s a part of history, it’s a part of boxing,” says Moorer of that night in November of 1994.

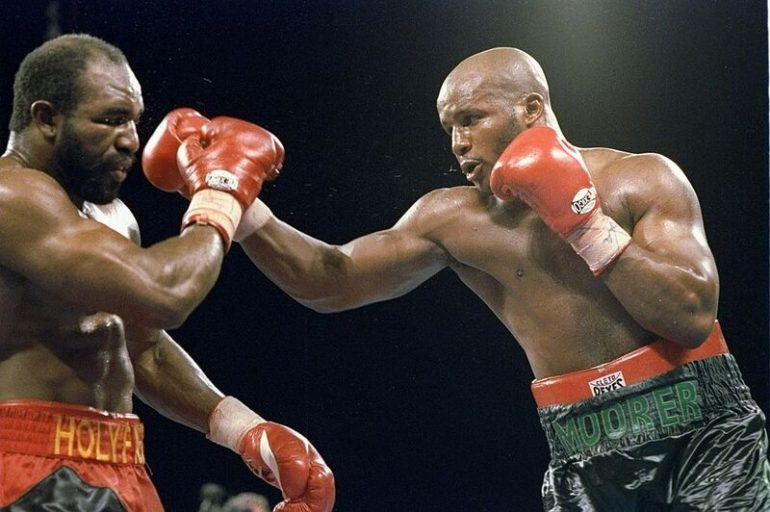

LAS VEGAS – MAY 5,1994: Michael Moorer (R) lands a punch on George Foreman in their 1994 fight. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

“I can’t criticize George or nobody on my end. I’m the only one who got in there and fought. He was victorious, it was something that happens in boxing. People seem to forget that at the drop of a dime the fight can change hands. All it takes is one punch. That’s all it took, that straight right hand.”

A rematch had been scheduled for 14 months later on Feb. 29, 1996 at Madison Square Garden, according to a New York Times article dated a month prior, but the fight reportedly broke down over monetary disagreements. Moorer believes there were other concerns at play.

“I wished the rematch would have taken place, I wanted to avenge my loss. George didn’t want to take the fight, he didn’t want to fight me. There was a rematch clause in the contract but he didn’t abide by it so he had to pay step-aside money I believe and the fight never took place,” says Moorer.

There were other fighters whom Foreman also wasn’t interested in fighting again. In his first outing after defeating Moorer, Foreman fought unknown German heavyweight Axel Schulz, winning a controversial majority decision. After declining a mandated rematch, Foreman was stripped of the belt and Schulz instead fought Frans Botha for the vacant title in December of 1995. When Botha failed the post-fight drug test, Schulz fought Moorer for the still vacant belt in June of 1996. Moorer made the trip to Germany to defeat Schulz by split decision to become champion once again.

Moorer says that is a testament to the character he has inside of himself.

“There’s a lot of people who don’t have that will. Luckily I had that will that once I lost, it’s not gonna keep me down. I can bounce back and keep winning and win another title. It was something that I was driven for. To go over there to Germany and feel the love that they had for me, it was phenomenal,” said Moorer.

Moorer’s first reign lasted just six months, but his second one would stretch for nearly a year and a half. He made a first defense against Botha, overcoming a sluggish start to batter the South African to a twelfth round stoppage, and a forgettable majority decision over Vaughn Bean which was marred by, among other things, the awkward jab-and-grab style of Bean.

He met Holyfield for a second time in November of 1997 in a unification bout of the WBA title Holyfield had won a year earlier in a massive upset over Mike Tyson and the belt Moorer was in possession of. This time, Holyfield was prepared for the southpaw style of Moorer. Following tactics similar to the ones employed by Foreman, Holyfield threw double left hooks to get Moorer, who was now trained by Freddie Roach, to move right, where he would meet him with the straight right hand.

Moorer was dropped five times but rose to his feet each time, with the stoppage coming in the corner after the eighth round.

Moorer remained out of the ring for three years afterward before returning to the ring in November of 2000, but his days as a serious contender were behind him. A thirty-second knockout loss to David Tua in 2002, plus a unanimous decision loss to Eliseo Castillo (while weighing a career-high 251 pounds) in 2004 showed that Moorer was not the fighter he had been a decade earlier, but he still had one last great performance left in him. Trailing badly to former cruiserweight champion Vassiliy Jirov in their bout in December of 2004, Moorer erased his deficit with a single left hand that dropped Jirov and prompted a referee’s stoppage. It was his version of the Foreman-Moorer comeback, though on a smaller scale.

Moorer would fight just five more times, winning all of them. He knew his bout with Shelby Gross on Feb. 8, 2008, a month shy of the 20th anniversary of his pro debut, would be his final ever. Entering camp at 275 pounds, Moorer trimmed down to a ripped 219 pounds, the lightest he had been since the Bean fight 11 years earlier. The fight lasted just 32 seconds as Moorer blew away the overmatched club fighter in Dubai before hanging up the gloves.

In the years following his retirement, Moorer has dabbled with training. He worked with former heavyweights J.D. Chapman and Mariusz Wach, plus a short stint as Roach’s assistant trainer as he prepared Manny Pacquiao for his 2009 fight with Ricky Hatton. He also worked at a gym called the Heavyweight Factory in Hollywood, Fla., where managers and trainers tried to turn former college football players into heavyweight boxers.

Moorer believes he still has plenty of guidance to offer young fighters as one of the rare champions who can boast of training under three Hall of Fame trainers. He still follows the sport closely, citing Shakur Stevenson, Terence Crawford, Devin Haney and Dmitry Bivol among his current favorites.

“Isn’t it amazing that I’m not training anybody right now? That is amazing to me. I know the game. I’m able to pass the lessons on if anybody was to call me in the heavyweight division or light heavyweight, especially southpaws,” said Moorer.

“If I could have gotten a hold of Errol Spence to fight Terence Crawford. See how his punches were coming so wide? I’m like, the hell are you throwing wide punches like that from a mile away? Terence saw it and capitalized on it. He would have never been punching like that if I had him, no way.”

Since Moorer made history as a southpaw heavyweight decades ago, other lefties, including Chris Byrd, Corrie Sanders, Ruslan Chagaev, Sultan Ibragimov and Charles Martin have won titles as well.

Currently, three of the major titles belts – plus The Ring heavyweight championship – are held by the southpaw Oleksandr Usyk. Like Moorer, Usyk came up in weight from a lower division, and is scheduled to face the much larger Tyson Fury for the undisputed title on May 18 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Moorer has an idea for how the fight will look.

“We hope it’s a good fight, it’s gonna be a technical fight because Tyson Fury is gonna use his reach to keep Usyk out away from him. Then Usyk is gonna keep trying to get in using body punches so he can drop his hands and try to come over the top. I’m sure [Usyk] has the endurance, I’m not sure if Tyson Fury is gonna have the endurance. Tyson Fury is gonna have to be in shape. Oleksandr Usyk is a great southpaw boxer, and Tyson Fury is a great boxer himself, so we’re gonna have to see what happens,” said Moorer.

When Moorer takes the stage in Canastota, he will do so as the 22nd former heavyweight champion to be inducted in the modern era category. He will be joining a group that includes only Michael Spinks and Roy Jones Jr. as one of the three boxers in that category to have won titles at light heavyweight and heavyweight.

What if? How about, what more?

“I just think it speaks for itself, I’m in the Hall of Fame. If you look that name up, Michael Moorer, then you’re gonna be intrigued by the style, the ability and him being a southpaw. I don’t see it any other way,” said Moorer.

Ryan Songalia has written for ESPN, the New York Daily News, Rappler and The Guardian, and is part of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Class of 2020. He can be reached at [email protected].