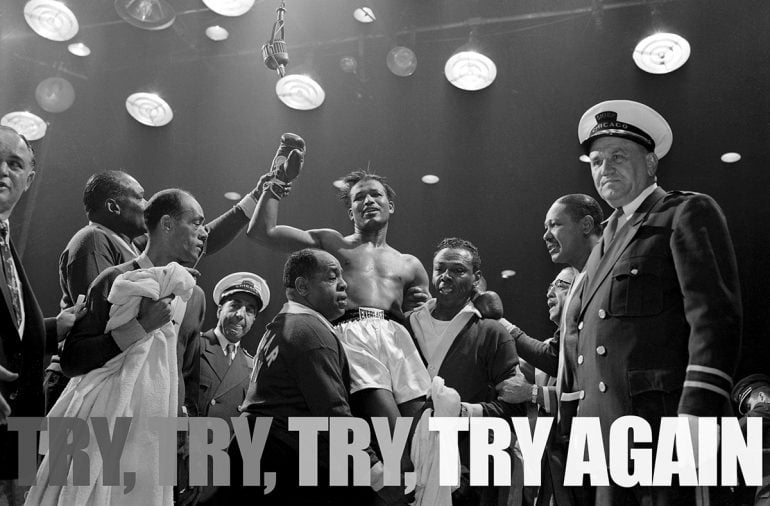

Try, Try, Try, Try Again

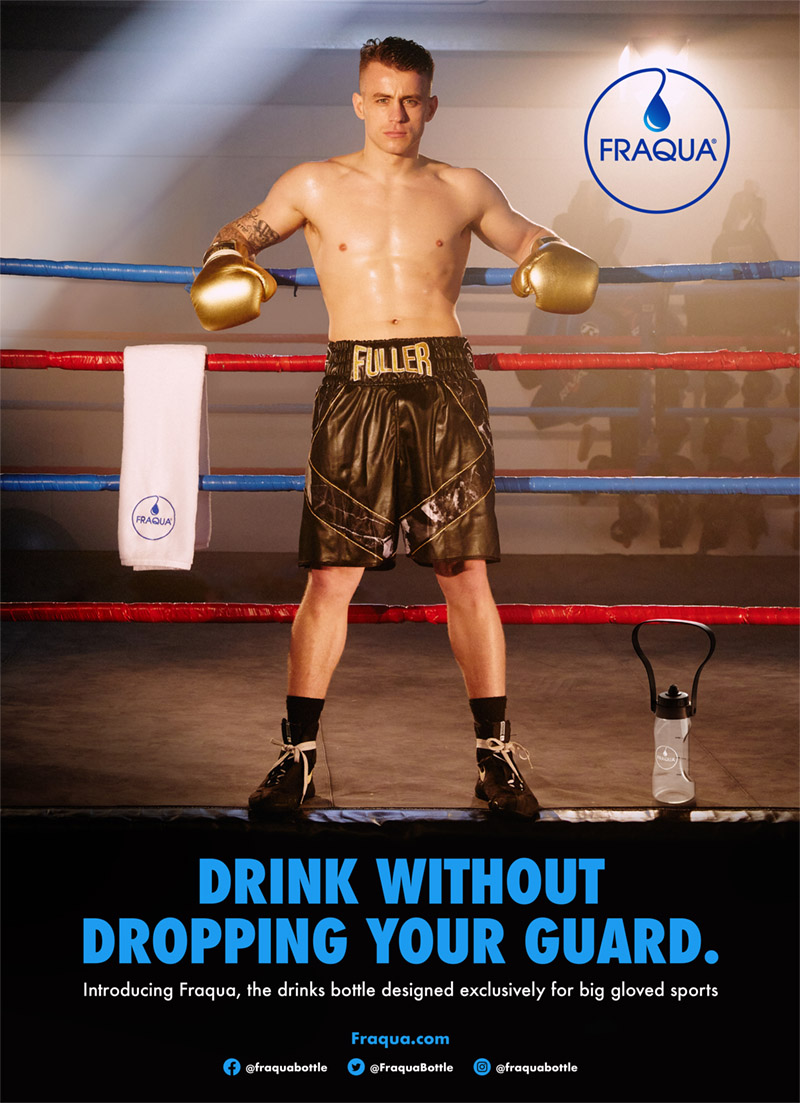

On this day (December 9) in 1955, former welterweight and middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson regained the 160-pound title with a second-round knockout of Carl “Bobo” Olson before 12,441 fans at Chicago Stadium in Chicago.

Robinson entered the bout as a 3-to-1 underdog despite carrying an amazing 137-4-2 record into the ring with his familiar foe. The 35-year-old veteran had not looked like the dynamo that ruled the 1940s following a near three-year retirement (from June 1952-January 1955) and had struggled during some of his six comeback bouts (including a 10-round decision loss to Ralph “Tiger” Jones and a hard-fought 10-round split decision over contender Rocky Castellani, who dropped the two-division champ for a 9-count in Round 6).

Olson, who entered the bout with a 71-7 record, had scored decisive victories over Jones and Castellani since winning the title with a 15-round decision over Randy Turpin (who also owned a victory over Robinson) in 1953.

However, Robinson regained his rhythm, timing and magic against Olson, who he had stopped in 12 rounds and outpointed over 15 rounds in previous bouts, stunning the rugged Hawaiian early in Round 2 and quickly overwhelming the future hall of famer nine seconds before the bell.

However, Robinson regained his rhythm, timing and magic against Olson, who he had stopped in 12 rounds and outpointed over 15 rounds in previous bouts, stunning the rugged Hawaiian early in Round 2 and quickly overwhelming the future hall of famer nine seconds before the bell.

“I didn’t get the title easy,” Robinson, overcome with emotion, said later in his dressing room. “I’m not going to give it away.”

Later in the decade, Robinson would “give” it away to a pair of future hall of famers, but he grabbed it back in epic rematches. Read about Robinson’s storied middleweight title bout wars during the 1950s in the following article, penned by historian Lee Groves and originally published in the July 2021 issue of The Ring, a special edition celebrating Robinson’s life and career (which is still on sale at the Ring Shop).

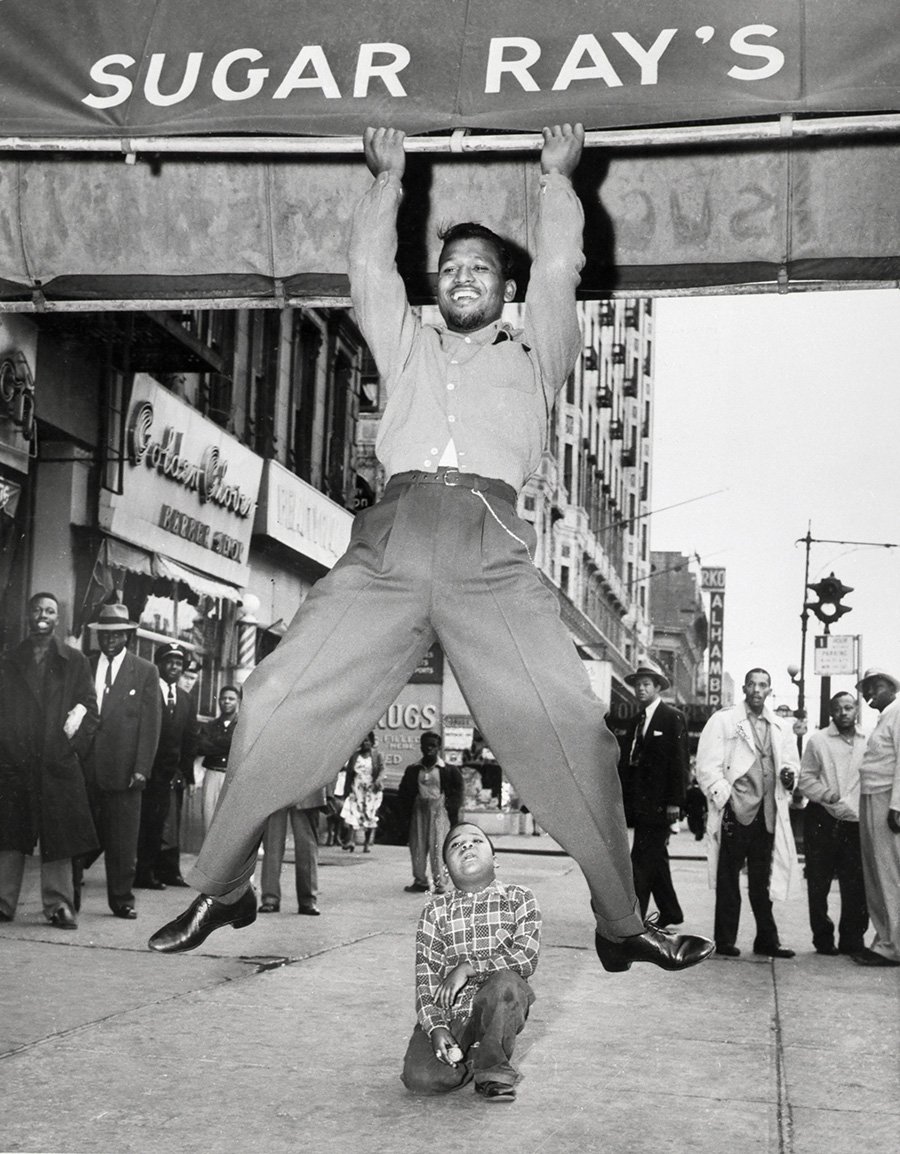

A REMARKABLE LEGACY ALREADY FIRMLY IN PLACE, ROBINSON TOOK A BRIEF STAB AT SHOWBIZ, BUT THE ALLURE OF THE CHAMPIONSHIP BELT PROVED TOO STRONG

For all world-class athletes, the ideal ending would be to gracefully leave the competitive arena at the absolute zenith, doing so with a healthy bank account, peace of mind and with a potentially lucrative second career in mind, if not in hand.

By announcing his retirement in December 1952, Sugar Ray Robinson, already considered the greatest pound-for-pound boxer in history as well as the most perfectly built pugilistic machine ever assembled, sought to execute the perfect exit strategy. At 31, Robinson was nearing the end of his chronological prime, and with a record of 132-3-2 with one no-contest and 87 knockouts, he was leaving behind a lifetime’s worth of memories for fans to savor. His post-career blueprint seemed sound; his Harlem-based businesses would provide him enough income to allow him to pursue his dream of being a song-and-dance man. By stepping away from boxing and time-stepping into the spotlight of show business, he hoped to embody the quote credited to P.T. Barnum: “Always leave them wanting more.”

Cosmetically, Robinson was up to the task, as he looked elegant in his white tie and tails. But after the initial rush of curiosity, it became clear that Ray Robinson the entertainer couldn’t match the matchless bar set by Sugar Ray Robinson the boxer. He was a decent tap dancer, but he was no Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. He could tell jokes, but he was no Bob Hope, Jack Benny or Milton Berle. And while his singing voice could ultimately be compared with those of Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali and Larry Holmes, he wasn’t in the same universe as those who stood atop Mount Olympus in their various genres.

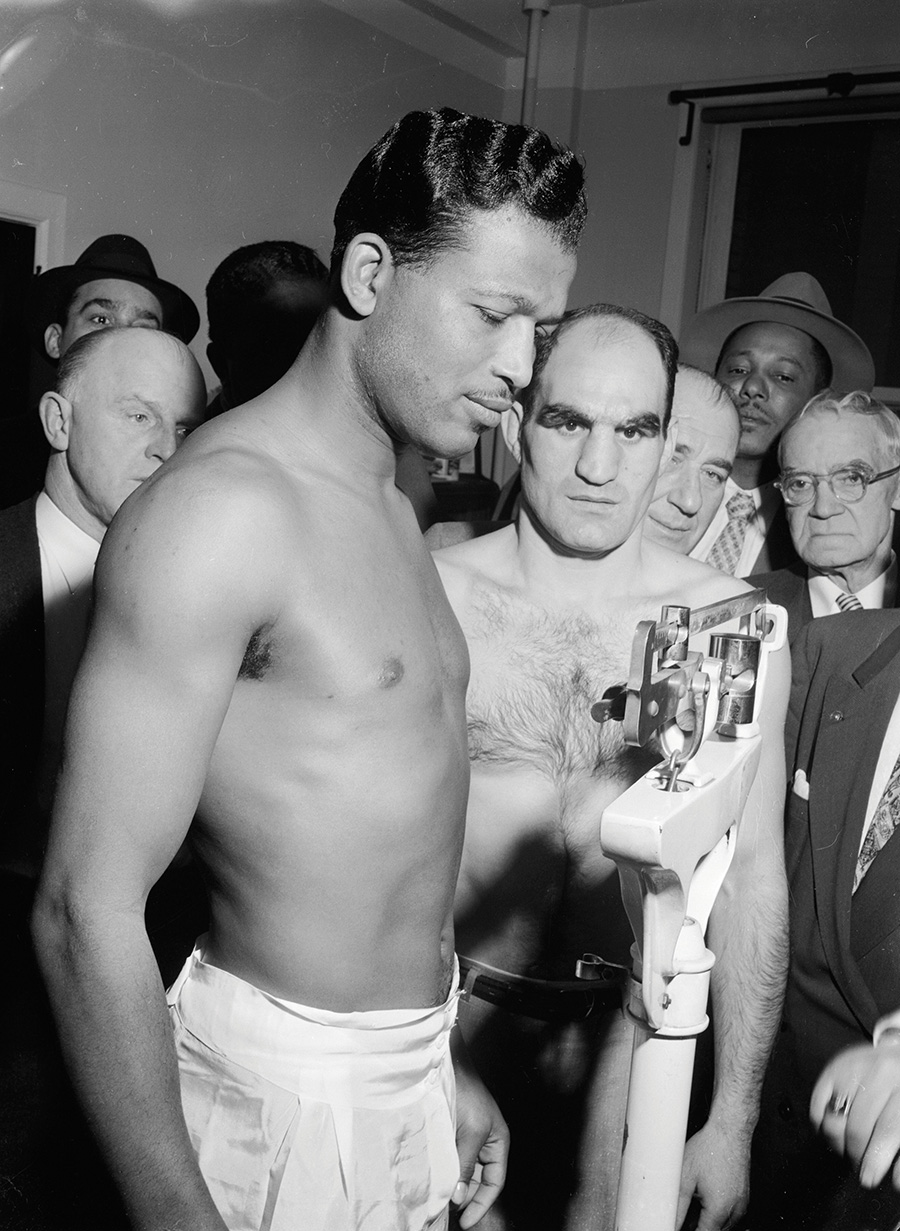

(Photo by Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

After the initial rush of curiosity, it became clear that Ray Robinson the entertainer couldn’t match the matchless bar set by Sugar Ray Robinson the boxer.

Robinson was honest enough with himself to realize he couldn’t achieve the perfection he wanted, and the harsh reviews took their toll on the gate as well as on his reputation. Robinson couldn’t stomach being mediocre, and rumors of a ring return were ignited when manager George Gainford was spotted with Robinson in Paris. Those rumors were further stoked by reports that his businesses were hemorrhaging money. It became clear that the income from his current gig couldn’t begin to repay his debts. A triumphant boxing comeback, however, could.

Another persuasive argument was that Carl “Bobo” Olson – whom Robinson had already beaten twice – was now middleweight champion, thanks to his victory over Randy Turpin in October 1953. Olson had won 18 straight since losing his second fight on points to Robinson in March 1952, including an 11th-round TKO over Pierre Langlois in December 1954 to retain his championship for the third time. Yes, Olson was on the best roll of his career – his other title-fight victims were the respected Rocky Castellani and welterweight king Kid Gavilan – but Robinson believed he could still take out Olson and regain the crown. All he had to do was win enough fights to justify the match, and if Robinson had his way, he would secure the showdown as soon as possible.

Following a 30-month layoff, Robinson was back against Joe Rindone.

The comeback began January 5, 1955, at Detroit’s Olympia Stadium against Joe Rindone, a Marine from Roxbury, Massachusetts, who was once rated seventh in the world. Robinson had stopped Rindone in six rounds in October 1950, and while he repeated that result here, the two-and-a-half years of rust was evident.

“For 10 exciting seconds, it was the Sugar Ray Robinson of old – swift, sharp and deadly,” wrote the Associated Press of the knockout sequence. “But before that, the sleek New Yorker was cautious and uncertain, showing obvious signs of his 30-month layoff.”

Two weeks later, Robinson appeared in his first nationally televised comeback bout against the rugged Ralph “Tiger” Jones, one of the era’s most popular “TV fighters.” Robinson was an 8-to-1 favorite against Jones, whose five-fight skid lowered his ledger to 32-12-3 with eight KOs. Once the opening bell sounded, however, the 26-year-old Jones unleashed the “Tiger” within and mauled the 33-year-old legend for 10 straight rounds. Shaken in the first, cut over the right eyebrow in the second and visibly tired after the fifth, Robinson lacked the strength, power and timing to cope with Jones’ attack. Jones earned an overwhelming points victory and, recalling Robinson’s heat-marred 14th-round TKO loss to Joey Maxim that ended the first phase of his career, the once-peerless Robinson had now lost two of his last three fights. In the very Chicago Stadium ring in which he dished out one of history’s most vicious beatings against Jake LaMotta, Jones inflicted what the Associated Press called “the worst beating of (Robinson’s) career.”

The loss scuttled a proposed third fight between Robinson and Gavilan as well as his hoped-for match with Olson. Meanwhile, the win earned Jones his own date with Olson, albeit a non-title 10-rounder, 30 days later. The fact that Olson fired a near-shutout against Jones (100-78, 100-86, 99-87) graphically illustrated just how far Robinson was from his ultimate goal.

“I want to continue,” Robinson told the AP. “I think Jones was too tough an opponent for a second fight. But being egotistical I wanted to take him on even though Joe Glaser (Robinson’s business manager) was against it from the start. I think I can do better with a few more fights, and if I can’t, then I’ll quit.”

Robinson returned two months later against Johnny Lombardo, whose record (32-12-2) was almost identical to Jones’ but was only a 2-to-1 underdog, a measure of how far Robinson’s regard had slipped. Another gauge was that the only people who saw the bout were the 5,124 inside the Cincinnati Gardens because it was not televised. Again Robinson struggled with his timing, but he showed enough flashes of his best self to win a 10-round split decision.

Robinson stuck with it, and, 16 days later, the sequence that ended his Milwaukee match against Ted Olla in Round 3 was an encouraging sign that Robinson’s previous speed and savvy were reawakening. Eighteen days after that in Detroit, Robinson survived a brief scare in Round 1 to comprehensively outpoint Garth Panter (100-77 twice, 99-81).

It was here that Robinson opted to roll the dice and see if he still had what it took to beat the top middleweights. The target was Castellani, who lost on points to champion Olson 11 months earlier but remained the top-rated challenger, thanks to subsequent wins over Moses Ward (TKO 8), Holly Mims (UD 12) and Chico Varona (UD 10). Castellani was a 2-to-1 choice, but Robinson forged an early lead by initiating most of the exchanges, showing sufficient strength in the clinches and focusing his attack on the body. But early in Round 6, Castellani maneuvered Robinson toward the ropes and connected with a crushing hook to the jaw that landed just as Robinson launched his own hook. The dazed Robinson fell forward to the canvas but regained enough of his faculties to rise at Jack Downey’s count of nine. Robinson rode out the round with several well-timed clinches, then rocked Rocky with a whistling right in Round 8 and controlled the ninth with several pinpoint power shots. The decision was split; Jack Silver’s 56-54 card for Castellani was heartily booed by the crowd inside San Francisco’s Cow Palace, but Silver was overruled by judge Frankie Carter and referee Downey, both of whom saw Robinson a 56-54 victor.

The Castellani victory capped a remarkable reversal of fortune; in a little more than six months, Robinson had risen from the ashes of the Jones loss and became the leading challenger for Olson’s championship.

Despite his two previous defeats to Robinson, Olson was a 3-to-1 favorite because (1) at 27, Olson was at his physical peak; (2) despite the Castellani victory, the skeptics doubted whether Robinson had the legs to last 15 rounds; and (3) when fighting near his own weight class, Olson was dominant. He barely lost a round in scoring 10-round decisions over “Tiger” Jones, Willie Vaughn and former light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim, the latter of which prompted Olson to challenge 175-pound king Archie Moore. “Ancient Archie,” still near his best at 41, dismissed Olson (who scaled a then career-high 170¼) in three rounds, but subsequent points wins over Jimmy Martinez and Joey Giambra, where he scaled 165 and 166 respectively, helped steady his ship. Meanwhile, Robinson was hit with a pair of distractions shortly before the December 1955 bout at Chicago Stadium: the gangland slaying of former business associate Alex Louis Greenberg (he and Joe Louis had the distributing rights for Greenberg’s Canadian Ace Brewing Co.) and an $87,000 federal tax lien on his earnings.

In a little more than six months, Robinson had risen from the ashes of the Jones loss and became the leading challenger for Olson’s championship.

The first round saw Olson pressing the action, but, unlike all of his other comeback bouts, Robinson appeared relaxed, confident and razor-sharp. His legs had spring, his reflexes were on point and he produced accurate counters immediately after avoiding Olson’s offerings. Robinson earned 10-9 scores from judges John Bray and Ed Hintz, but referee Frank Sikora scored it even.

Round 1’s pattern continued until the waning moments of the second. As Olson moved in, Robinson landed a piercing left uppercut that caused the champion to pause. Seeing Olson was buzzed, Robinson missed with an overhand right, then landed a sweeping hook, a chopping right and a final left uppercut that caused Olson to topple backward. Olson managed to scramble to his feet, but only after Sikora finished his 10-count. At 2:51 of Round 2, Robinson had become the first man to win the middleweight championship three times.

“It seems like almost a miracle,” the joyous Robinson declared. “I’m a Christian. I did the very best I could and left the rest to God.”

Robinson’s “retirement” had its fun moments, but it was nothing compared to wearing the middleweight crown again.

Five months later at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field, Robinson completed his four-fight sweep over Olson by scoring a fourth-round KO. Just like in fight three, the time of the stoppage was 2:51.

Following a non-title 10-round decision over Bob Provizzi in November 1956, Robinson faced Gene Fullmer, the barrel-chested son of a copper miner from West Jordan, Utah, who , at 25, was nearly a decade younger. Though named for the stylish Gene Tunney, Fullmer, a pleasant, gentle man outside the ring, was a crude, stone-faced brute with an iron chin and endless stamina inside it. He had many of the ingredients Turpin, “Tiger” Jones and LaMotta used to defeat Robinson, but Robinson looked so good in destroying Olson in back-to-back title fights that he still was a 6-to-5 pick.

Robinson’s first appearance inside Madison Square Garden since his 62-second starching of Flashy Sebastian in August 1947 was grueling, punishing and messy – just the way Fullmer liked it. Fullmer absorbed Robinson’s thunder with aplomb, he manhandled the champion in the clinches, and it was he who scored the fight’s only knockdown in Round 7. The decision for Fullmer was unanimous, and it wasn’t close (10-5, 9-6 and 8-5-2 in rounds).

Just as Olson secured an immediate rematch upon losing his title to Robinson, Robinson got the instant second chance at Fullmer on May 1, 1957 – two days before his 36th birthday. A good omen for Robinson was that the fight was staged at Chicago Stadium, the site of his title-winning triumphs against LaMotta and Olson as well as his three-round starching of Rocky Graziano. The smart money, however, was behind Fullmer, the 7-to-2 favorite. Complaints about Fullmer’s rabbit punching and Robinson’s holding prompted the Illinois Athletic Commission to inform both fighters that fouls wouldn’t be tolerated, and thus the first four rounds assumed a wait-and-see pattern peppered by occasional but brief skirmishes. All three judges had Fullmer ahead 19-18 under the five-point must system.

Then came Round 5 – and the blow that came to be known as “The Perfect Punch.”

In a scene that appeared much like the final moments of the third Olson bout, Fullmer walked toward Robinson with his right hand positioned slightly lower than it should have been. Seeing this, Robinson uncorked a beautifully timed 45-degree hook to the point of the chin that caused Fullmer’s tree-trunk legs to collapse. Fullmer’s mind desperately wanted his body to rise, but he was counted out because it refused to comply.

Robinson vs. Fullmer

“Never seen the punch coming,” Fullmer told author Thomas Hauser years later. “I don’t know anything about the punch except I’ve watched it on movies a number of times. The first thing I knew, I was standing up. Robinson was in the other corner. I thought he was in great condition, doing exercises between rounds. My manager crawled in the ring. I said, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘They counted 10.'”

The first man ever to win the middleweight title three times now was the first to win it four times.

Seated at ringside was Robinson’s next opponent, undisputed welterweight champion Carmen Basilio. The onion farmer from Canastota, New York, initially was a Robinson admirer, but that changed when he introduced himself to Robinson only to be brushed off. That act ignited a hatred that not only fueled Basilio for their September 1957 clash at Yankee Stadium, but for the remainder of his life.

The 5-foot-6½-inch Basilio – a surprising 6-to-5 favorite – overcame his pronounced height, reach and weight disadvantages the only way he could: by getting inside Robinson’s longer arms and ceaselessly pounding every available target. Robinson’s slashing blows cut Basilio’s left eye in the fourth, but the challenger/champion fought through the blood, shrugged off Sugar Ray’s torpedoes and withstood a spirited late-round rally to capture a well-received split decision that was later deemed The Ring’s Fight of the Year. With the win, Basilio joined Robinson as the only reigning welterweight champions to dethrone a defending middleweight king.

The quality of their first meeting justified an immediate rematch in March 1958 at Chicago Stadium, Robinson’s “lucky” building and the site at which Basilio had gone 0-3, including a scandalous points loss to Johnny Saxton that ended his first welterweight reign. As good as Fight One was, Fight Two was even better as they produced a scintillating spectacle while also fighting through tremendous physical challenges – a high fever for Robinson and a hideously swollen left eye for the 2-to-1 pick Basilio, the result of a Robinson uppercut late in Round 5.

“I got stupid that night,” Basilio told author Peter Heller. “He kept throwing a right uppercut at me that night. He knew that I bobbed and weaved, and he tried to catch me going down. He’d throw it, I’d go down, I’d catch his right uppercut with my right hand, and I’d counter him with a left hook because he was wide open for it. I did it four times. The fifth time he threw it at me and I saw it coming. I missed it with my hand, and it hit me right in the eyebrow and broke the blood vessels.”

Robinson defeats Carmen Basilio for his fifth middleweight title.

Basilio continued to fight savagely despite the severe handicap, but Robinson was more than equal to the task as he twice staggered Basilio in the 14th and stunned him in the final round with shots to the injured orb.

“Trying to stop him was like trying to stop a freight train,” Robinson told reporters later. “I feel like 10 guys jumped me.”

Once again, the decision was split. But this time Robinson was the victor, the first fighter ever to win the same championship on five occasions. And, like Basilio-Robinson I, Robinson-Basilio II was The Ring’s Fight of the Year.

Read “Robinson-Basilio 2: Warfare Never to be Seen Again” by Bernard Fernandez

Visions of a third meeting with Basilio, as well as a fantasy fight against light heavyweight monarch Moore, danced inside many heads, but those dreams remained dreams because financial terms couldn’t be reached. Thus, Robinson was out of the ring for nearly 21 months and the National Boxing Association – the forerunner of today’s WBA – stripped Robinson of its title for inactivity and awarded the belt to Fullmer, thanks to his 14th-round TKO over Basilio in August 1959. After stopping New England light heavyweight champion Bob Young in two rounds at the Boston Garden, Robinson returned there in January 1960 to face Paul Pender, a Korean War veteran who retired in 1956 due to chronic hand injuries. After a stint with the Brookline Fire Department, Pender returned to the ring after 23 months away and won nine straight to earn a No. 10 rating and a shot at Robinson. The 5-to-1 underdog’s sharp boxing and superior speed was good enough in the eyes of two judges to become the new champion in the eyes of Massachusetts, New York and The Ring.

Robinson exercised the rematch clause and, after a first-round KO of Tony Baldini in April, met Pender less than five months later, again at the Boston Garden. And, once again, Pender won a split decision that was much better received than the first, thanks to his taking command in the middle rounds with superior infighting.

“I wasn’t rusty,” Robinson said, his voice barely above a whisper. “I just didn’t have what it takes to win. I tried to finish strong. But the judges made the decision; I didn’t.”

By now, Robinson was a pale shadow of the master who dominated the 1940s and early 1950s. His trigger was slower, his legs were heavier and his reflexes were duller, and yet he appeared to extract one final miracle when he met Fullmer in December 1960 at Los Angeles’ Sports Arena. His middle-rounds surge combined with a huge 11th-round rally prompted many to believe he had done enough to earn a sixth middleweight title reign. A poll of 23 ringside reporters saw Robinson ahead 14-6-3, and referee Tommy Hart agreed by submitting an 11-4 card in his favor. But judge Lee Grossman’s 9-5 score for Fullmer negated Hart while judge George Latka’s 8-8 card led to a title-retaining draw for Fullmer.

The furor justified a fourth Fullmer-Robinson match, but while the 40-year-old icon performed well, the 30-year-old champ fought better as he nearly stopped Robinson in the third and hustled his way to a decisive, if somewhat uncomfortable victory.

(Left to right) Randy Turpin, Gene Fullmer, Carmen Basilio and Carl “Bobo” Olson hold Robinson aloft.

Robinson fought on for four and a half years, winning most but losing often enough to keep him away from the title picture. He had enough in the tank to beat future junior middleweight champions Denny Moyer and Ralph Dupas but not enough to vanquish Terry Downes, Joey Giardello, Stan Harrington (twice), Mick Leahy and Memo Ayon. And yet, a 44-year-old Robinson was only one victory away from a final chance at glory, for the winner of his November 1965 contest against No. 1 contender Joey Archer was promised a fight with middleweight champion Dick Tiger.

Though Robinson boxed well in the early rounds, the relatively light-hitting Archer delivered a hard reality check in the fourth after a long, chopping right to the jaw floored Robinson for a nine-count. Archer nearly added a second knockdown in the sixth, seventh and 10th en route to a decisive points victory that dropped Robinson’s record to 174-19-6 with two no-contests and 109 knockouts. Robinson announced his retirement the following day.

Three weeks later, Robinson was given a grand send-off at Madison Square Garden. He was joined by Fullmer, Basilio, Olson and Turpin, and as they posed for photographers, they were showered with cheers. It was the storybook end to what had been a magnificent quarter-century of excellence.

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 19 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics and the co-author of Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers.