After 40 years, Aaron Pryor-Alexis Arguello 1 still among the greatest matchups of all time

Some of the most memorable fights in boxing history are commemorated in large part because of a controversial ending or an unusual in-fight occurrence. Set pieces that fall into that category, wholly or in part, include Mike Tyson’s “Bite Fight” disqualification loss to Evander Holyfield, Julio Cesar Chavez’s 12th-round stoppage of Meldrick Taylor only two seconds from the final bell in JCC’s desperate bid to pull out a victory in a fight he was losing on the scorecards, and Jack Dempsey’s “Long Count” points setback to Gene Tunney, in which the “Manassa Mauler” refused to promptly go to a neutral corner after registering a seventh-round knockdown, giving Tunney precious additional seconds to recover. Fans are left to forever speculate and debate as to how those and similar asterisk-highlighted bouts might have concluded for historical purposes had circumstances played out a bit differently.

“I knew that in the final rounds the man would be divided from the boy.”

– Aaron Pryor

A familiar addition to the list of “what-if?” matchups is the November 12, 1982, battle that pitted Ring/WBA junior welterweight champion Aaron “The Hawk” Pryor against Ring/WBC lightweight titlist Alexis Arguello in Miami’s Orange Bowl. Conspiracy theorists, mostly those who supported Arguello, hold firm to the notion that the Nicaraguan national hero, who was bidding to become the first boxer to win widely recognized world title belts in four weight classes, was the victim of shenanigans orchestrated by Pryor’s shady and later-disgraced trainer, Panama Lewis. The outcome of the savage, two-way battle was still seemingly in doubt when, during the one-minute break between Rounds 13 and 14, Lewis told another of Pryor’s cornermen to give him a black water bottle, “the one I mixed,” which led to speculation it contained an illegal and performance-boosting substance. After taking a swig or two from the bottle, Pryor – who had been fighting at his characteristically furious pace since the opening bell – again came out blasting, initiating a sequence in which he landed 15 unanswered blows that sent Arguello slumping to the canvas, where he remained unconscious for nearly four minutes. Arguello finally was revived after receiving oxygen, but nearly seven minutes had elapsed before he could be helped onto his stool, after which he was taken to a nearby hospital for observation.

The fact that Lewis eventually served prison time for removing glove padding and doctoring the handwraps of his fighter Luis Resto, an underdog journeyman who administered a particularly brutal beating to hot prospect “Irish” Billy Collins on June 16, 1983, gave some credence to the possibility that Pryor might also have benefited from unpermitted assistance from his chief second in the first of his two classic showdowns with Arguello. But Pryor made a strong case that he needed no such help, as his 14th-round flurry was in line with the torrid pace he had maintained all along. And his even more emphatic 10th-round knockout of Arguello in their September 9, 1983, rematch at Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace seemingly ended most if not all doubt as to who was the better of the two future Hall of Famers, at least on the nights in question.

Pryor was known for his menacing intensity.

And if all that weren’t enough, Arguello, who later became fast friends with Pryor — as can happen with fighters who earn one another’s undying respect in the cauldron of the ring — said he harbored no lingering suspicions that the Cincinnati native had gained an advantage from the contents of the notorious black bottle, which was not examined by the same Florida boxing commission that also failed to subject Pryor to urinalysis testing. Lewis steadfastly maintained that the only thing in the bottle was peppermint schnapps.

“There are 24 rounds between us that I can never forget,” Arguello told me during the IBHOF’s 1995 induction festivities, which he attended along with Pryor. “From the first round of the first fight, when the bell rang, we gave 100 percent of ourselves.”

And the “black bottle” brouhaha?

“I did my best,” Arguello shrugged. “The other guy did better. That’s simple enough to understand.”

Also simple to understand is that those 24 rounds of trial by combat have so risen in legend and lore that the status of their rivalry, especially the 14 rounds of their epic first meeting, now are viewed as more meaningful than they were the night that the combatants electrified an on-site crowd of 23,800, a remarkable turnout considering that the telecast was also readily available to HBO subscribers in Dade and Broward counties. Consider this: Pryor-Arguello I was not The Ring magazine’s 1982 Fight of the Year; Bobby Chacon’s 15-round unanimous-decision dethronement of WBC junior lightweight champion Rafael “Bazooka” Limon was. But lack of that designation, as it turned out, did not prevent Pryor-Arguello from receiving a major upgrade eight years later. By the end of the 1980s, The Ring had proclaimed Pryor-Arguello I as its Fight of the Decade, in addition to being the eighth-greatest boxing match ever. There are those who would say that its place on the all-time pecking order might also gain some upward mobility if the electorate was called upon for a revote.

None of the plaudits going to a truly great test of wills and skills would be flowing so freely had not the action inside the ropes justified it, but the lead-up to fight night checked off all the boxes for creating interest that spread nationwide (and beyond) like wildfire. For one thing, the in-their-prime pairing of two of boxing’s best was the first major bout staged in the Miami area since Muhammad Ali, still then known as Cassius Clay, gave pretty strong evidence that he really was the “Greatest,” or soon would be, with his sixth-round stoppage of heavily favored heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in the Miami Beach Convention Center.

The Ring’s November 1982 issue

Even more so than boxing’s long-delayed grand return to Miami, however, the matchup of the 27-year-old Pryor, who entered the ring with a 31-0 record with 29 knockouts, and the 30-year-old Arguello, who came in with a 72-5 mark with 59 KOs, represented all that boxing is supposed to be but isn’t as often as it should be. (See the maddeningly long delay in making the Floyd Mayweather Jr.-Manny Pacquiao megafight, or the ongoing difficulty in pairing Errol Spence Jr. and Terence “Bud” Crawford for the undisputed welterweight championship.) Pryor-Arguello was widely viewed as a 50/50 fight of two outstanding fighters, with vastly different styles and personalities, while they were at or near their peak efficiency.

Pryor’s hard trek to success from a lifetime of poverty, and the assortment of grudges that can arise from his dire youthful circumstances, stamped him one of the angriest of his sport’s angry young men, maybe as much as his frenetic, nonstop punching style. “The Hawk” (named so “because I swoop down on my opponents,” he explained) not only threw punches in bunches, he fired away as if his finger was always pressed down hard on the trigger of a pugilistic machine gun with an unending belt of bullets. As his stature grew with each knockout (he arrived in Miami with a streak of 21 consecutive victories inside the distance), so were fight fans increasingly familiarized with his dysfunctional childhood and adolescence. And the formidable punching power Pryor so frequently exhibited on the way to achieving elite status had done nothing to lift the Sequoia-sized chip off his shoulder.

Arguello vs. Cornelius Boza-Edwards in 1980.

Denied a place on the 1976 U.S. Olympic boxing team because of a loss at the Trials to eventual gold medalist Howard Davis Jr., Pryor chafed at having to turn pro with a string of below-the-radar fights for three-figure purses while Davis signed a $1.5 million contract with CBS. Pryor also was resentful of the fact that the most popular of America’s breakthrough stars of the ’76 Montreal Olympics, Sugar Ray Leonard, did not use his considerable clout to get him in any of the televised preliminary bouts on Leonard’s high-profile cards. Incredibly, Pryor did not appear on national TV until his 22nd pro bout.

In a profile of Pryor for Sports Illustrated, Pat Putnam wrote that “his lifestyle outside the ring is, unfortunately, as confusing and destructive as his tactics within it.” Still, for all Pryor’s inability to comfortably fit within polite society, Putnam acknowledged that he “without question is the most exciting fighter in the world. He fights like a driven, obsessed man, and in a way that’s manifested by a quest for acceptance.”

Everything about Pryor stood in stark contrast to the flawless and pristine image in and out of the ring presented by Arguello, who steadfastly declined to engage opponents in pre-fight trash-talking. Even after Pryor tried to get under his skin by sarcastically calling him “Alice” after their fight date was first announced, Arguello refused to respond in kind, and his effusive praise of the man with whom he would swap punches even had the effect of getting Pryor to tone down his normally inflammatory rhetoric. But that didn’t mean Pryor felt he was being accorded the same respect from the media and public as was being shown to Arguello.

“I’m 31-0, 29 knockouts, and still proving myself,” he complained. “Every time I fight, my opponent’s supposed to be so good before the fight, but after I beat him they write about what he was and what he used to be.”

Perhaps because Miami has such a large Latino population that has always been supportive of one of its own, Arguello — who turned pro at bantamweight, was making the jump from 135 and would be fighting for the first time at 140 — was getting most of the sports book action. For those favoring Arguello, another step up in weight did not matter much, if at all. Maybe that’s because they remembered how dominant he had been in dethroning Scotland’s Jim Watt for the Ring/WBC lightweight championship on June 20, 1981, in London.

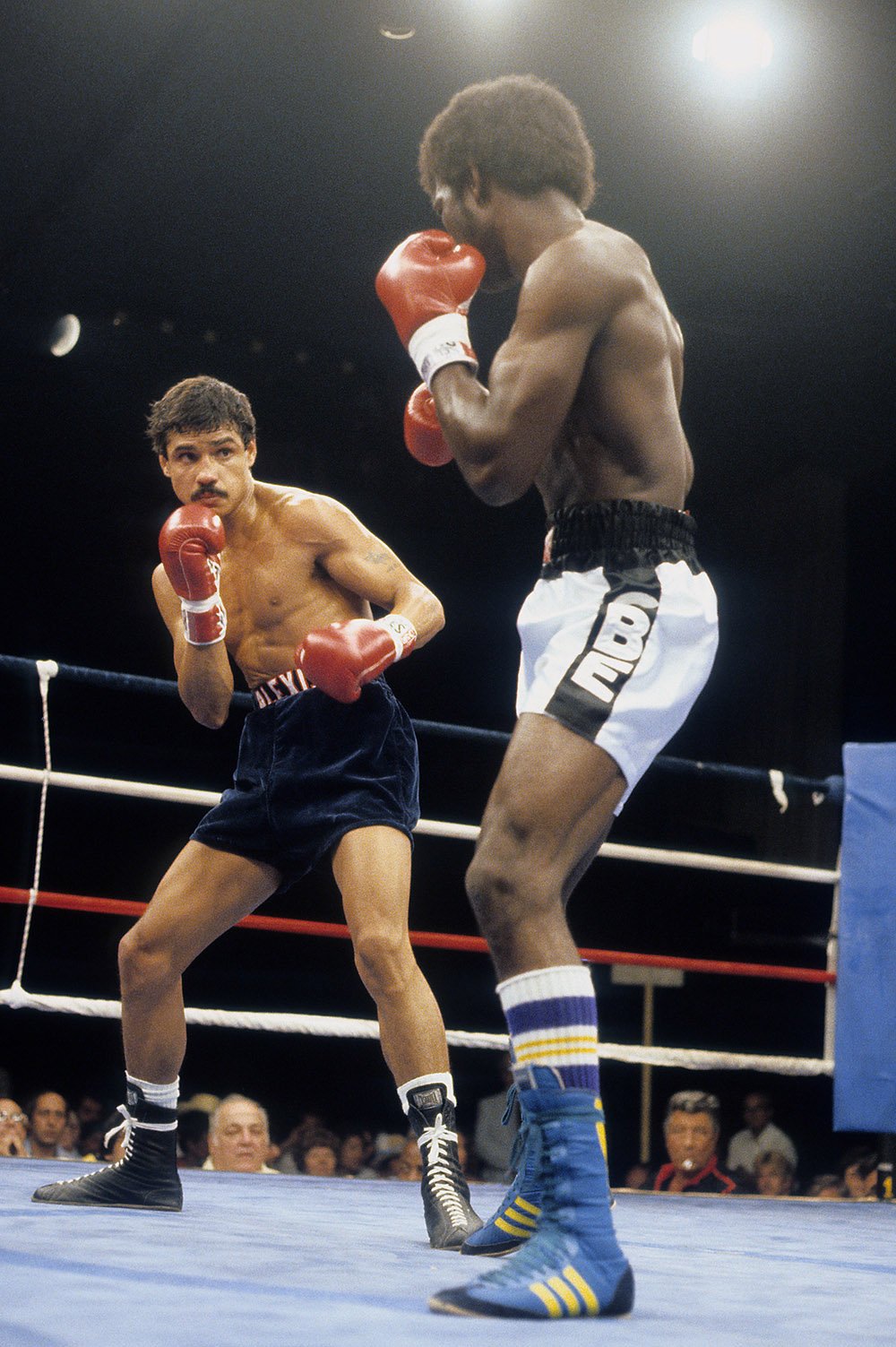

Arguello had early trouble dealing with Pryor’s aggression. (Photo by Manny Millan /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

“I have a car business, and if I had to do an estimate on my face, I’d say it’s totaled,” Watt said of the gory reflection he saw in the mirror in his dressing room.

Others picking Arguello reasoned that his non-frenzied demeanor and laser-accurate counterpunching would largely neutralize and ultimately overcome Pryor’s hair-on-fire tactics from the opening bell. “I’ll take precision any day over power,” Arguello said when asked how his more patient style matched up against Pryor’s. “If he starts with fire, we might be playing with fire. I don’t know.”

Regardless of who all the media types saw as the eventual winner, most envisioned a fight that would live up to the runaway hype.

“This is a great fight, everything you want,” mused Ferdie Pacheco, Muhammad Ali’s personal physician and an NBC TV boxing analyst. “You have a good-looking, polite gentleman and the bizarre villain. ‘The Hawk’ can only fight exciting – he has a hysterical style and he’s one of the toughest little guys I’ve seen. You’ve got to kill him to get him out of the ring. But I can’t see how he can overcome all the experience and the beautiful style of Arguello.”

Arguello began to find his mark more often in the middle rounds. (Photo by Manny Millan /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Pacheco’s view was more or less seconded by the Miami Herald’s esteemed sports columnist Edwin Pope, who had been a collegiate boxer at the University of Georgia. Pope wrote that “I just think the hummingbird (Arguello) will dodge the hurricane (Pryor).”

Taking a contradictory position were the Miami-based Dundee brothers, Chris and Angelo, who felt that Hurricane Aaron represented howling winds and a tidal surge too high and powerful for even Arguello to withstand indefinitely.

“I take Pryor,” said Chris. “Too strong, too young, too much pressure.”

Added Angelo: “I make it a very tough fight. Everybody seems to be picking Arguello. I lean a little toward Pryor. One thing that offsets a precision fighter like Arguello is a fighter you can’t program. And you can’t program Pryor. You don’t know which way he’s going to come at you.”

The main event was preceded by a spectacular fireworks display (and a loaded undercard that featured appearances by three former world champions, including Roberto Duran) that hinted at what was to follow. As expected, Pryor went at Arguello as if he were a cavalry commander leading the Charge of the Light Brigade. Maybe not as expected to some, Arguello had difficulty settling into a rhythm in the face of such unabated ferociousness.

“One thing that offsets a precision fighter like Arguello is a fighter you can’t program. And you can’t program Pryor.”

– Angelo Dundee

But Arguello began to find openings to place stinging shots in the middle rounds, which had the effect of inciting Pryor to again pick up the pace. He came out for the 14th round reinvigorated – maybe because of the contents of the mysterious black bottle, and maybe not – and his frantic flurry caused referee Stanley Christodoulou to step in and wave things off at the 1:06 mark. It went into the books as a TKO, as Christodoulou did not bother to initiate a count as an out-cold Arguello slowly slid to the canvas.

Pryor celebrates as Arguello collapses on the ropes. (Photo: The Ring)

The official scorecards entering the climatic 14th round had Christodoulou and judge Ove Ovesen of Denmark favoring Pryor by 127-124 margins while judge Ken Morita of Japan saw Arguello ahead by 127-125.

“I tornadoed him the first five rounds, then he started picking me apart in the middle rounds, but I stormed back,” said Pryor, who was paid a career-high $1.6 million (after a slim payday of just $100,000 for his preceding defense, a sixth-round stoppage of Japan’s Akio Kameda on July 4, 1982) to $1.5 million for Arguello. “He weathered the storm early. He’s a great champion — not was, but is. It was an educational fight for me. He showed me a lot. He showed me there are some guys who have a heart as big as mine.

“Arguello is very strong, the hardest puncher I’ve ever faced. But he never had me worried. I never thought it was over. At the end of the 11th round, I yelled to Arguello, ‘Come on, this is it. Let’s fight.’ I knew that in the final rounds the man would be divided from the boy … At the end of the fight, it sort of reminded me of Muhammad Ali’s bout with Larry Holmes. I looked at Alexis and I sort of felt sorry for him.”

Referee Stanley Christodoulou cradles the fallen Arguello. (Photo by Manny Millan /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Writer John Crittenden praised Arguello as having “movie-star looks and a gentleman’s manners” and “the stuff that brought honor to this pugnacious game. He was a breath of fresh air in a sport filled with the smell of stale cigar smoke and sweat.”

All well and good, but Arguello’s good manners ultimately were trumped by what Pryor brought to the fray, described by Crittendon as “eyes wild with the fury he would soon send into his fists.”

The rematch, won more convincingly by Pryor, was not the end of the tale involving two future inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame (Pryor was inducted in 1996, the capstone to a great career in which he went 39-1 with 35 KOs, and Arguello in 1992 with an 82-8 mark with 65 KOs). Both fighters returned to Canastota, New York, on several occasions, and in tandem they were among the most sought-after targets of autograph-seekers who recognized how they were destined to march into history as individuals and as partners in an epic rivalry that has endured the test of time.

“It’s like a dream come true every time I’m here,” Pryor told me in 2013 of the rush he always got from showing up for the IBHOF induction festivities, which he did 20 times. “You can get hooked. If you come once, you’re probably going to come year after year after year. To me, it’s one of the greatest feelings you could ever have to come to this special place. I look forward to it like a little kid looks forward to Christmas. The fans just take you in. They embrace you.”

Interestingly, the angry bad boy of boxing that Pryor had been found a measure of peace years after he conquered an opponent even more daunting than Arguello. He took his first hit of cocaine days after his second confrontation with Arguello, in “The Hawk’s” adopted hometown of Miami, where, I wrote, “pharmaceutical escapes from reality were as much a part of the landscape as palm trees and white-sand beaches.” It wasn’t too long that his addictions, taxes and alimony from two failed marriages ate away at his ring earnings until nothing was left.

“After Buddy (LaRosa, his estranged manager) took his half, the government took its half (of what was left),” Pryor said. “Then after that, my wife at the time had to have her half. After everybody got their half, I didn’t have half of nothing.”

Pryor was sentenced to prison on a drug conviction in 1991, and the following year he was a homeless crack addict living on the streets of his hometown of Cincinnati, shadowboxing in alleyways for handouts that might allow him to score his next drug hit. His weight dwindled to 100 pounds or so, and he admitted to considering suicide. But Pryor found love and redemption with his third wife, Frankie, also a recovering cocaine addict. By the time of his induction into the IBHOF, he was clean, and he remained so until his death, 11 days before his 61st birthday on October 20, 2016. His listed cause of death was heart disease, very likely accelerated by his cocaine addiction, but he had found the sort of contentment that proved so elusive even during his championship reign.

Arguello, the shining knight of his sport, took a turn for the worse after retirement, and for reasons that had once bedeviled Pryor. He was 57 and the mayor of Managua, Nicaragua’s capital, when he died on July 1, 2009, reportedly of a self-inflicted gunshot to his head, although many continue to believe foul play was involved. His apparent suicide came after his own descent into drug addiction and financial and marital difficulties.

Where Pryor and Arguello rate among the all-time greats continues to be a matter of individual or formulaic perspective. The Ring, using a complex system in which points were awarded on a variety of weighted scales, listed Arguello as the 22nd best fighter of the magazine’s 100-year existence in its February 2022 collector’s issue, with Pryor – arguably the best junior welterweight of all time – far back in the pack at No. 80. Another collector’s special, from June 2022, had Arguello at No. 18 of the 100 greatest punchers of the last 100 years while Pryor didn’t make the cut at all.

So let the arguments begin, or at least continue. What is indisputable is that two men, so alike in some ways and so starkly different in other ways, made magic on the night of November 12, 1982. Fight fans everywhere can only hope that Spence and Crawford, if they ever are to share the spotlight, can produce more of the same.

More from The Ring:

“KO Magazine 1986: Alexis Arguello — The Guts and the Ability are Still There”