Evander Holyfield-Bert Cooper: The near-upset 30 years later

Many of boxing’s most memorable upsets, and even the near-misses, represent truth at two linked but sometimes distinctly different levels. One is what everyone sees with their own eyes: punches thrown and landed, or missed, at key moments forever frozen in time; a referee’s call at a crucial point in the action; even the site of a fight can present a unique set of ramifications.

But the accompanying truth often is less discernible to those not afforded the privilege of peeking behind the curtain. Expected outcomes fail to materialize because of a favored fighter’s overconfidence, or an underdog’s dogged determination to elevate to a higher performance plane. Even individuals not directly involved in a highly consequential bout can have a bearing on what takes place inside the ropes. A cross-section of all such factors coalesced for what is widely considered the most shocking result in ring history, Buster Douglas’ 10th-round knockout of seemingly invincible heavyweight Mike Tyson on Feb. 11, 1990, in Tokyo. Did Tyson take the talented but chronically underachieving Douglas, a 42-1 no-hoper, too lightly? Without a doubt. But just as significant a factor in the outcome was Buster’s zealotry in dedicating the fight to his recently deceased mother.

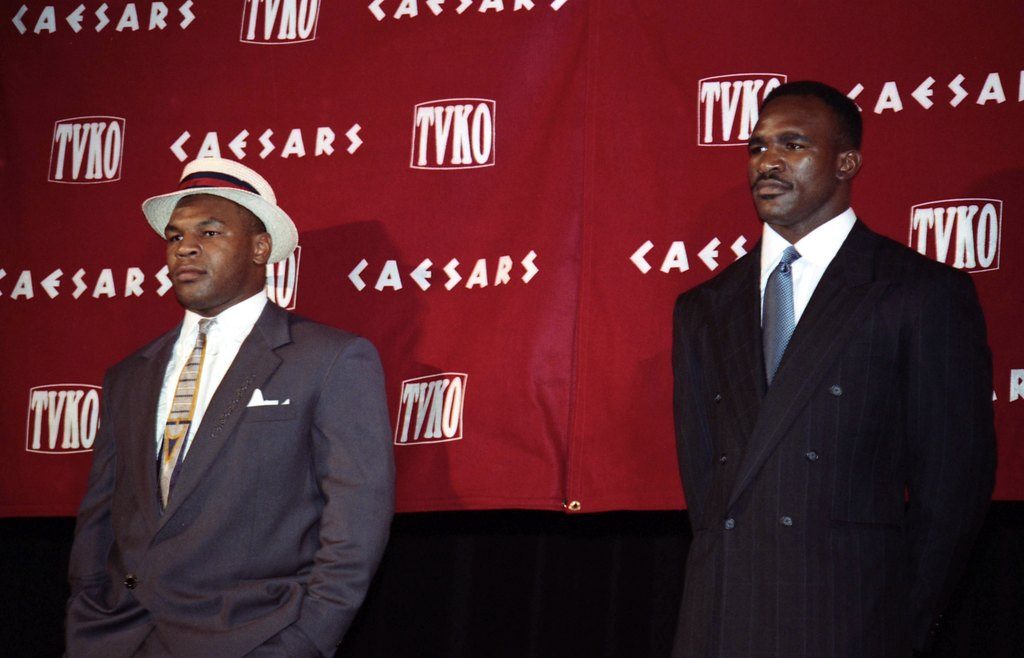

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Today marks the 30th anniversary of Douglas conqueror Evander Holyfield’s precarious escape against “Smokin’” Bert Cooper, a late replacement for a replacement, in Atlanta’s since-demolished Omni, in what generally had been presumed to be a hometown victory lap for the new champion in his second title defense. But Cooper, nearly as long a longshot at 32-1 as Douglas had been against Tyson, badly hurt and floored (at least officially) Holyfield in the third round, and might have finished him off right then and there had not referee Mills Lane given the champ a standing-eight count. “The Real Deal’s” undefeated record (he had come in 26-0 with 21 KOs) and brief reign might have gone up in, well, smoke were it not for those few seconds of rest. When an overanxious Cooper rushed in again to try to finish him off, Holyfield – whose recuperative powers were and are well-documented – answered with a barrage of his own that carried him to the end of the shakiest round of his professional career to that point.

“My heart started to go boom, boom, boom,” Cooper said when asked for his reaction to the sight of Holyfield in trouble. “I thought I was the heavyweight champion of the world. I said to myself, `Oh, boy, this is it.’”

But with the bell ending the round, the window of opportunity closed for Cooper. Holyfield began to reassert control in the fourth round, and as the seventh round was nearing a close, he landed 21 unanswered punches. Lane stepped in, wrapped his arms around the bloodied Cooper and waved the fight to a halt after an elapsed time of 2 minutes, 58 seconds. Former heavyweight champion George Foreman, a color analyst for the HBO telecast, said the fight was “the best I’ve seen,” but he criticized Lane’s actions in both the third and seventh rounds.

“He saved Evander (in the third round), yet, when he stopped the fight, he didn’t give the other guy a standing eight-count,” Foreman offered. Lane defended his judgment call to give Holyfield the standing-eight because, although the champion remained mostly upright as he sagged against the ropes, because his right glove had brushed the canvas, thus constituting a knockdown.

And Holyfield’s seventh-round flurry that sent Cooper, who did not go down, reeling?

“Cooper had lost the ability to defend himself,” said Lane, a banty rooster of a referee and actual courtroom judge who seldom if ever second-guessed himself. “He was just getting nailed and nailed and nailed. They took turns shellacking one another, but early in the fight when both were hurt, they still had that resiliency to come back.

“It was obvious to me that Cooper wasn’t about to come back that last time. There was no point in him taking any more punishment. He’s a hell of a man who fought a hell of a fight. He should be proud.”

Not surprisingly, neither Cooper nor his controversial promoter, Rick “Elvis” Parker, saw the stoppage as justified. “They bring Bert in on short notice, they pay us one-sixth of what Evander gets and then they rob us,” complained Parker, who also charged that a 2½-minute delay in the fifth round to allow Holyfield’s corner team to replace a split glove was an intentional ploy to give their presumably gassed fighter needed respite from Cooper’s relentless pressure.

“He’d given Bert his best shots, and he didn’t have much left after that,” Parker continued. “It just seems very convenient that he came up with the problem with his glove at that particular time. I don’t blame the referee for that happening. I blame Holyfield’s corner.”

Said Cooper: “(Holyfield) knew he was dead in that fifth round if he didn’t get that timeout. He was dead-tired, and he was just trying to hold on. I showed tonight that I can dish it and I can take it. Even though I don’t have the belts (the WBA’s and IBF’s were on the line), I’m the champ.”

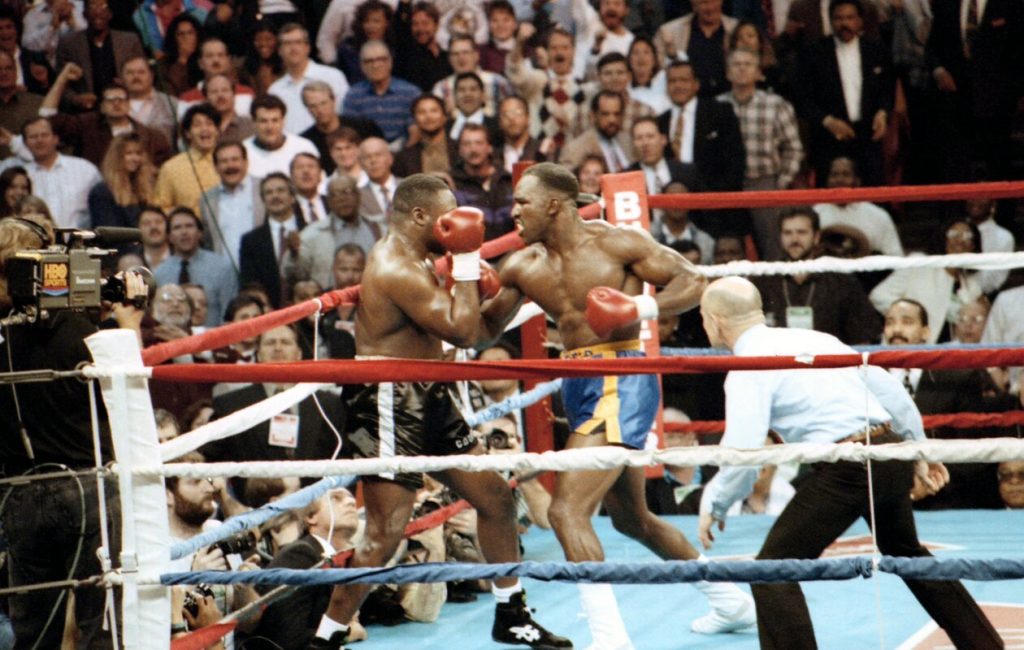

Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

The passage of 30 years has a way of obscuring fact, be it real or perceived, from fiction. Unlike Douglas, whose miracle in the Land of the Rising Sun shall forever remain the stuff of legend, Cooper – whose once-shiny potential was tarnished by years of drug abuse and an unrepairable falling-out with his hero, mentor and role model, Joe Frazier – became a lesser footnote in the big book of boxing history. He was just 53 when he passed away at his home in Philadelphia on May 10, 2019, the result of a bout he was doomed to lose with pancreatic cancer. An inductee into the New Jersey (2014) and Pennsylvania (2017) Boxing Halls of Fame, he took his earthly 10-count with a final mark of 38-25, with 31 wins inside the distance but also 16 defeats in similar fashion. He was just 11-17 in his last 28 ring appearances.

“Bert Cooper wasn’t at his best,” a sadly reflective Cooper said in assessing his roller-coaster career during a 2015 interview. “The majority of my career, I wasn’t at my best.”

Upon further reflection, any suggestion that Cooper could or should have dethroned Holyfield that chilly night in Atlanta three decades ago is, at best, speculative. Yeah, the percussive overhand right to the jaw in the third round that put Holyfield squarely in the danger zone was the night’s most dramatic blow, but statistics furnished by CompuBox reveal that the champion was on target with 459 punches, including 275 power shots, while Cooper connected with a total of just 233. At the time of the stoppage Holyfield was well ahead on the scorecards, by margins of 59-53, 59-54 and 58-54, and was seconds away from likely expanding his lead by two more points on each had the bell ending the seventh round sounded. Holyfield even had matched Cooper’s knockdown by dropping the challenger in the first round with a ripping left hook to the ribs.

“He hit me with a good shot, but I feel like I had everything together,” Holyfield said of the opportunity of a lifetime Cooper had momentarily presented himself with in the third round. “My mind was there. But Bert Cooper fought his heart out, and I have to commend him for that. He had that, you know, brute strength. He was aggressive enough to make me fight in a way I didn’t want to fight.”

That pretty much sums up what was discernible to the casual fight fan via the standard eye test. It is on that other level, the one stashed behind the curtain, that shades Holyfield-Cooper with the sort of nuanced perspective that is as much or more a part of the complete picture as that which took place inside the ring.

After he had starched Douglas in three rounds on Oct. 25, 1990, Holyfield defended his titles for the first time with a 12-round unanimous decision over Foreman on April 19, 1991, in Las Vegas. Next up would be former champ Tyson in a megafight set for Nov. 8 of that year, also in Vegas. But Tyson injured his ribs in training and the fight was tentatively postponed until sometime early in 1992, a date which would also go by the wayside when Tyson subsequently was convicted of raping a teenage beauty pageant contestant in Indianapolis, Ind. But Holyfield, who had already put in much work in the gym, was primed and ready to fight somebody in the fall, so the date and venue were changed to Nov. 23 in Atlanta, with Italy’s Francesco Damiani, the former champion of the then-lightly-regarded WBO, tapped to replace Tyson.

Holyfield-Tyson fell through in 1991. Photo by The Ring/ Getty Images

Damiani, however, also was obliged to withdraw after he sprained an ankle in training on Nov. 14, forcing Holyfield’s promotional company, Main Events, to find a fighter further down the bench who was ready to jump in on one week’s notice. That call went to Cooper, a short, stumpy physical prototype of Tyson as well as of Joe Frazier.

“I guess all the work Evander put in getting ready for Tyson won’t go to waste now,” Holyfield’s lead trainer, George Benton, said when Cooper drew the assignment. “Fighting Cooper is a lot like fighting Tyson. They’re both short, strong guys who come straight at you and try to rough you up. They both have that kill-or-be-killed attitude.

“I don’t know if Cooper is the closest thing to Tyson, although he’s pretty damn close in some ways. But let’s be honest. In other ways, they don’t really compare at all. Cooper doesn’t punch as fast or as hard as Tyson, and he doesn’t take a shot nearly as well. Tyson does a lot of smart things for a slugger. Cooper basically is a brawler. Tyson is the real thing. Cooper is not on the same level. Still, it should be an entertaining fight for as long as it lasts.”

Ron Katz, then Top Rank’s East Coast matchmaker, had used Cooper in the past and he was thinking of putting him in with Bruce Seldon in January. Katz said that proposed fight might have meant a $15,000 payday for Cooper, who suddenly found himself with a contract to swap punches with Holyfield for $750,000.

“Talk about something good falling into your lap,” Katz said of Cooper’s unexpected stroke of luck. “God bless him, he’s getting the opportunity of a lifetime. But I would have thought I had a better chance of hitting the lottery than Bert Cooper of getting a shot at the heavyweight title. It’s a sad commentary, really. The TV date was set, though, and I guess the show has to go on.”

The selection of the unranked Cooper to replace Damiani did not meet with widespread approval. Murad Muhammad, the promoter of world-rated Donovan “Razor” Ruddock, described the gig that went to Cooper as “ludicrous. Razor Ruddock has been training for 2½ months. He’d have been honored to fight Evander Holyfield, but no one asked us. Every fighter in the top 10 should be screaming his head off.”

Ivan Cohen, Cooper’s former co-manager, also was among the dissenters. “That’s not a competitive matchup,” Cohen groused. “You got a shot fighter (Cooper) against a robot (Holyfield). It goes two rounds, tops, before the robot wins.”

Detecting the silver lining in the dark clouds so many others were envisioning was Ross Greenburg, the executive producer for HBO Sports. “The most ironic thing about the fight is that whenever anyone was going to fight Tyson in the past, they would call Cooper as a sparring partner because of their similarities. It’s ironic now that Holyfield would end up fighting a Tyson look-alike.

“Before a fight, you can speculate all you want on the abilities of an opponent. A lot of people were speculating on Buster Douglas (before he took down Tyson), and not very favorably, I might add. But look what happened.”

Holyfield on the attack. Photo by The Ring Magazine/ Getty Images

Just as Buster Douglas had vowed to himself to shock the world and defeat Tyson as a tribute to his late mom, Lula Pearl Douglas, Cooper was spurred to put everything he had on the line in defiance of his onetime idol, Frazier. The two had grown close in the years that Cooper had trained at Frazier’s gym in North Philly, so much so that when Bert turned pro he adopted Joe’s “Smokin’” nickname. But the relationship had turned frosty, with no indication of a thawing.

“Pop looked upon Bert almost as a member of the family,” recalled Joe’s son, Marvis. “He treated him better than he did me. Well, almost.”

But there were strict dictums all Frazier family members and proteges were expected to observe: No drugs. Give until it hurts. And never, ever betray a trust. Cooper’s drug use, which he had been successfully concealed for several years, violated one of those tenets, and so, too, did his public complaints about how Joe had mandated that he move up from cruiserweight to heavyweight.

After Cooper, who had been 16-1 as a cruiserweight, was stopped in eight rounds by Carl “The Truth” Williams on June 21, 1987, he said, “I realized I’m not a heavyweight. I put on a lot of phony weight just eating sloppy stuff, junk food … Joe wanted me to be a heavyweight, just like he did with Marvis. Joe wants someone with a world title belt just like he had.”

Smokin’ Joe took that rebuke as another violation of trust, and he told Cooper he no longer could serve as his manager. Try as he might to restore what had been lost between them, Cooper was rebuffed at every turn.

“I try to speak to him, but he acts like he doesn’t see me,” Cooper said of Frazier before the Holyfield bout. “There’s bad blood between us, but it’s mostly on his side. I still love the guy, but Smokin’ Bert Cooper and Smokin’ Joe Frazier do not mix. Not anymore.

“When I was a kid, he used to open up his coat and say, `Here, kid, take your best shot.’ I’d like to take that shot now.’”

Might Cooper have been seeing Joe Frazier when he delivered his best shot to Holyfield’s jaw? Perhaps. But he couldn’t quite close the deal, although the intensity of a fight that many had presumed would be an Evander romp turned out to be anything but.

Curiously, Mike Boorman, then a spokesman for Main Events, said the paid attendance of 12,996 in the Omni Coliseum that night, although a good and enthusiastic turnout, was not a sellout and that some ticket-purchasers had asked for and received refunds when it was announced that Cooper would pinch-hit for Damiani.

“We tried to explain to everyone that Cooper actually was a tougher fighter, but nobody believed us,” Boorman said. “That’s the problem with being a promoter. When you tell the truth, nobody believes you. It’s like the boy who cried wolf.”

Still another addendum to the Holyfield-Cooper week that was in Georgia’s largest city: Two future heavyweight champions and Holyfield opponents, Lennox Lewis and Michael Moorer, appeared on the undercard. Lewis stopped Tyrell Biggs in three rounds in a pairing of the 1988 and ’84 Olympic super heavyweight gold medalists, while Moorer ran his professional record to 26-0 with 26 KOs with a one-round blowout of Bobby Crabtree.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE