A Fan Remembers Tyson-Berbick 35 years later

Thirty-five years ago today, Mike Tyson completed his rise to superstardom by destroying Trevor Berbick in two rounds to capture his first slice of the heavyweight championship. In doing so, “Iron Mike,” at 20 years 150 days, became the youngest boxer ever to win a widely recognized heavyweight title belt, although he wouldn’t earn full recognition until after he crushed Ring Magazine and lineal champion Michael Spinks (who beat the previous “Man” Larry Holmes in 1985 and was stripped of his IBF belt for fighting Gerry Cooney instead of mandatory challenger Tony Tucker) in June 1988.

From the moment Tyson-Berbick was announced, there was an overwhelming sense of inevitability that harkened back to past heavyweight championship fights between supremely talented challengers and overmatched defending champions:

* Although Tommy Burns was a 3-to-2 favorite to defeat Jack Johnson in December 1908, those odds were more the product of wishful thinking and overt racism than sober analysis, and “The Galveston Giant” proved his superiority over 14 tortuous rounds.

* Joe Louis was a solid 5-to-2 choice to dethrone defending champion James J. Braddock, the “Cinderella Man” who overcame 10-to-1 odds to dethrone Max Baer more than two years earlier. Despite being dropped in round one, “The Brown Bomber” carved up the game Braddock before taking him out with a trademark right cross to the jaw in round eight.

* Floyd Patterson’s manager Cus D’Amato shielded his charge from the terrifying Charles “Sonny” Liston for years, and while Patterson managed to overrule his manager, D’Amato was emphatically proven correct once the opening bell sounded. The man dubbed “The Big Ugly Bear” by his improbable successor Cassius Clay (later to be known as Muhammad Ali) needed just 126 seconds to justify the 8-to-5 odds in his favor.

And so it was with Mike Tyson versus Trevor Berbick on November 22, 1986, a fight whose story I told exactly five years earlier on RingTV.com. The piece you will read today recounts my memories of the buildup as well as of the contest.

This fight was the continuation of a $26 million heavyweight title unification tournament arranged by HBO and promoters Don King and Butch Lewis, known at the time as “The Dynamic Duo,” and when Tyson earned his spot in the bracket by blowing out former cruiserweight champion Alfonso Ratliff in two rounds on the undercard of Michael Spinks-Steffen Tangstad that September 6, the buzz surrounding the tournament became a swarm. That’s because of the excitement “Kid Dynamite” brought to the table, not just inside the ring, but beyond the ropes as well.

Tyson-Berbick took place just days before my 22nd birthday, so Tyson was a contemporary in terms of age. But I had been a keen boxing observer for more than 12 years, and never before (or since) has a prospect excited me as much as the ascendant Mike Tyson. The first reason for this was that he looked like a man who could become a dominant heavyweight champion. At 5 feet 11 ½ inches (as measured by HBO) and scaling between 212 and 221 ½ pounds, Tyson sported a granite-like physique, a basic close-cropped old-school haircut and a snarl that could send shivers down the backs of even the toughest men.

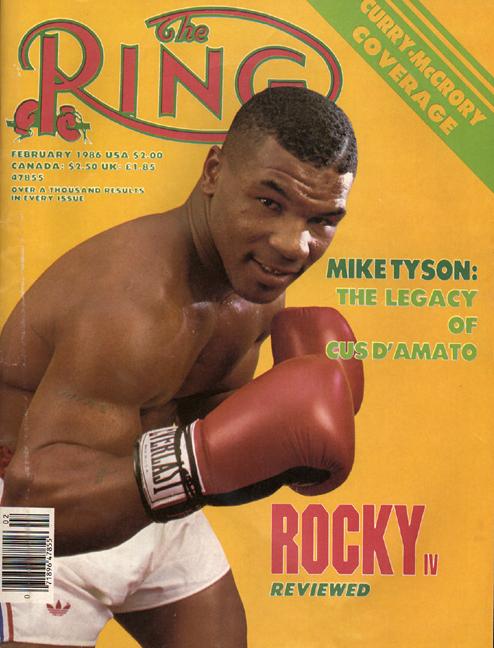

Tyson’s first Ring Magazine cover – February 1986.

The second reason was his multi-dimensional talent. One would expect a man of Tyson’s build to possess crippling power in both fists, but what separated Tyson from other heavyweight bombers such as Dempsey, Louis, Rocky Marciano, Liston, Earnie Shavers and George Foreman was his supersonic hand speed. Up until this point, Patterson arguably had the fastest hands in terms of delivering power combinations, but Tyson, who scaled 30-40 pounds heavier, was capable of landing four bombs on a heavy bag within one second. He transferred his gym speed into the ring, and even at his young age, his imagination was such that he created a trademark combination: A right to the body immediately followed by a right uppercut to the jaw.

The third reason was the extraordinary sophistication of Tyson’s overall game. Tyson was the perfect exponent of the D’Amato system described in great detail in the book “Non-compromised Pendulum” by Dr. Oleg Maltsev and D’Amato mentee Tom Patti. Every punch is set up by a series of precisely timed moves, and much like a quarterback in a run-pass-option offense, the boxer is challenged to make split-second decisions in terms of which punch (or which combination) to throw based on what his opponent presents to him at any given moment; a dynamic that requires above-average intelligence, excellent hand-eye coordination and supreme perceptiveness. The boxer is similarly challenged on defense, and D’Amato’s approach required swaying the upper body from side to side while keeping the hands in a peek-a-boo position. Hundreds of hours of drilling are required to create the necessary muscle memory to execute this approach, and while D’Amato proteges Patterson and Jose Torres incorporated several of these elements into their games, Tyson illustrated them to the fullest degree – and he did so brilliantly.

The final element was that Tyson, thanks to the years he spent watching co-manager Jim Jacobs’ massive boxing film collection, possessed a deep knowledge of boxing history, so much so that he co-hosted an ABC special with Alex Wallau entitled “Tyson and the Great Heavyweights.” His bowl haircut was a tribute to Dempsey and his habit of walking to the ring without a robe further illustrated his throwback mentality. He believed that if this Spartan approach was good enough for the old-timers, it was good enough for him.

While I heard Tyson’s name from time to time during the lead-up to the 1984 Olympics (he lost to eventual U.S. representative and gold medalist Henry Tillman at the U.S. Olympic Trials and Box-Offs), I became fully aware of him when he made his national TV debut against Ricardo Spain in June 1985 as part of ESPN’s “Top Rank Boxing” series. Jesse Ferguson vs. Tony Anthony might have been the main event, but it was Tyson’s 39-second destruction of Spain that created the deepest imprint. The win lifted his record to 4-0 (4 KO) and from there the combination of Tyson’s whirlwind schedule and the media savvy of co-managers Jacobs and Bill Cayton lifted Tyson’s profile to stratospheric heights. The January 6, 1986 cover of Sports Illustrated perfectly illustrated the flavor of the hype surrounding him: Tyson, striking a relaxed boxing pose and flashing a gap-toothed grin, is surrounded by the words “Kid Dynamite” and “Mike Tyson: The Next Great Heavyweight – and He’s Only 19.”

The excitement continued to build, and that was magnified by the fact that Tyson was a fearsome, perfectly conditioned athlete while several of the leading heavyweights of the time – Greg Page, Tony Tubbs and Tim Witherspoon – were more fleshy than flashy. Tyson also upped the verbal ante by declaring that “I wanted to hit (Jesse Ferguson) in the nose one more time so that bone could go up into his brain.” The masses wanted their heavyweights strong, intimidating, powerful and vicious, and the Mike Tyson who was set to challenge Berbick checked all of those boxes.

Unlike Tyson, Berbick was an Olympian; in the space of 11 amateur fights, he won a bronze medal in the 1975 Pan American Games and won a berth on Canada’s 1976 Olympic team. Unfortunately for him, he lost his only bout to eventual silver medalist Mircea Simon of Romania, who lost the gold medal bout to defending Olympic champion Teofilo Stevenson. Berbick’s global reputation as a pro was forged by his stunning ninth round KO over former heavyweight champion John Tate on the undercard of Roberto Duran-Sugar Ray Leonard I, his courageous but losing 15-round decision loss to WBC heavyweight champion Larry Holmes three fights later and by being the final professional opponent of Muhammad Ali, whom he defeated on points in December 1981. The 6-foot-2, 218 ½-pound Berbick sported a thick, muscular torso, sturdy legs and a solid, though not perfect, chin. While it is true that Bernardo Mercado crushed Berbick in one round in April 1979, his other losses to Holmes, Renaldo Snipes and ST Gordon were on points, and he earned his second crack at a heavyweight championship by winning eight straight fights following the back-to-back defeats to Snipes and Gordon. His victims included David Bey (KO 11) and Mitch “Blood” Green (majority W 12), but despite his recent run of success he still was a 6 ½-to-1 underdog to undefeated WBC heavyweight king Pinklon Thomas, who was touted as the heir apparent to Holmes thanks to his ramrod jab and crisp right crosses.

Berbick greatly enhanced his chances of victory by hiring legendary trainer Eddie Futch, whose conditioning techniques and sage advice brought out the best in the Canada-based Jamaican. Berbick’s brute strength (and Thomas’ party-hearty lifestyle away from the ring) resulted in the crowning of a new champion. With the victory, Berbick moved on to the next round of the HBO tournament, but it wasn’t until Tyson annihilated Ratliff that he knew the identity of his opponent – and the threat said opponent posed to his championship.

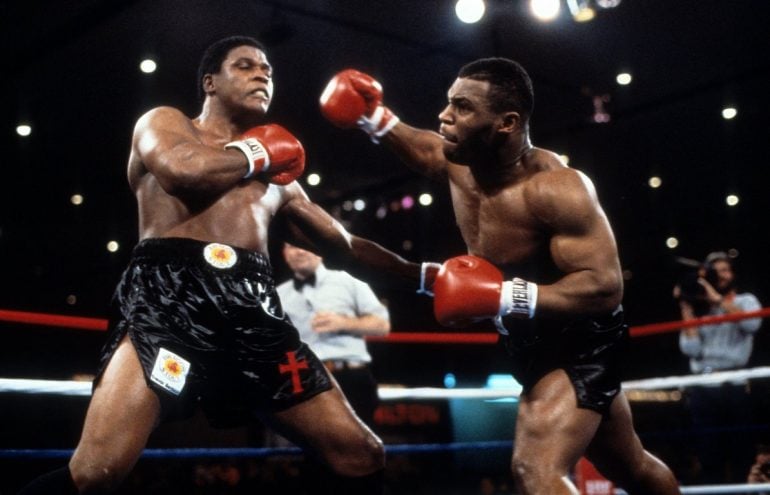

Prime Mike Tyson prior to fighting Jose Ribalta. He weighed in at 213 pounds for that 1986 bout. Photo from The Ring Archive

Tyson opened as a 6-to-1 favorite against Berbick, but by fight time they dropped to 3 ½-to-1 because some thought that despite owning a 27-0 (25 KO) record, Tyson might be biting off more than he was ready to chew. Meanwhile, Berbick had switched trainers since dethroning Thomas, but while losing the wisdom and calm of Futch was always a negative, Berbick did his best to compensate by hiring the venerable and fiery Angelo Dundee.

My feelings about the outcome mirrored the conventional wisdom: Tyson was justifiably favored and I thought he would prevail inside the distance. The only question was when Tyson would lower the boom, and given Berbick’s track record of durability I thought it would happen during the middle rounds.

I did not see the fight live on HBO – I did not yet have the descrambler needed to decrypt the signal – but thanks to the C-band dish I saw the international broadcast that featured future Hall of Famer Col. Bob Sheridan, who presided over the vast majority of Don King promoted shows. No matter who was doing the call, the excitement quotient was the same, and, for most of us, it was all about Tyson. As I awaited the ringing of the opening bell, I instantly knew that win or lose, I was about to witness a touchstone moment in boxing history; either Tyson would fulfill the lofty expectations of a hopeful public and a watchful media, or Berbick’s bulk, strength, resilience, experience and pride would graphically expose Tyson’s previous unearthed weaknesses. For these reasons, “Judgment Day,” the title affixed to the main event, was most appropriate.

From the very start, it was evident that Tyson was the force we all thought he was. He demonstrated stone-cold calm as he executed move after move and landed punch after punch while Berbick showed no respect for his precocious challenger and did his best to answer every Tyson blow with one of his own. In the closing seconds of Round 1, a four-punch salvo drove Berbick backward, and at the bell a defiant Berbick raised his chin, stuck out his mouthpiece and defiantly taunted his opponent.

The atmosphere in each man’s corner couldn’t have been more different. Tyson’s chief second Kevin Rooney was the picture of serenity as he leaned in toward Tyson’s ear and told him to “stay very calm. Look to place the body shots first and then the head. Great round.”

Meanwhile, Berbick’s corner was unsettled, uncoordinated and chaotic, which, given Dundee’s reputation for meticulous preparation, was startling. Dundee handed an ice pack to one assistant, who had to be told twice to place it on the back of Berbick’s neck. The other assistant was wiping Berbick down with a sponge while Dundee leaned down to look for that very same sponge. Exasperated, Dundee yelled “where’s the f***ing sponge?” Once he was handed the sponge, Dundee dropped it onto the canvas and by the time he began issuing instructions, 31 seconds of the rest period had already passed.

Any doubts of an impending Tyson coronation disappeared in the opening seconds of Round 2 when Tyson scored the first official knockdown with a big combination punctuated by a right to the ear. Berbick jumped to his feet before referee Mills Lane could issue a count and he spent the rest of Lane’s mandatory eight count bracing himself for Tyson’s follow-up assault. Berbick survived the next wave but he couldn’t withstand the following one as Tyson landed a short right to the ribs, missed a huge right uppercut and connected with a final hook to an area between the temple and the bridge of Berbick’s nose. The effects of the final punch acted like a time-release capsule that assaulted the champion’s central nervous system in most memorable fashion. Here is how I described the final sequence five years earlier:

Berbick crashed back-first to the canvas and, here, the civil war between his massive competitive drive and his badly compromised motor skills began. Berbick managed to raise himself to a knee but when he tried to push himself up the leg collapsed and propelled him to the ropes. He then used his left glove to push down on the bottom rope but, when he tried to use his right leg to haul himself up, the limb failed him again. With Lane still counting, Berbick tried to rise a third time. Here he managed to get to his feet but his glassy, half-open eyes and blank expression told Lane everything he needed to know. At 2:35 of the second round, Lane confirmed the transfer of power with a wave of his arms.

“It’s over,” intoned HBO blow-by-blow man Barry Tompkins. “That’s all. And we have a new era in boxing.”

Tyson didn’t just knock out Berbick, he bewildered and overwhelmed the veteran with his power, speed, footwork and technique. Photo by Focus on Sport/ Getty Images

Tyson’s superiority and air of invincibility was such that Tompkins made the same leap we all did in that moment: Not only did we witness the crowning of a new world champion, we also saw the beginning of the next defining era for “The Sweet Science.” The mantle that once belonged to John L. Sullivan, Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano and Muhammad Ali now belonged to a 20-year-old from the Brownsville section of Brooklyn.

By disposing of the rugged Berbick so resoundingly, and looking at the list of challengers that lay before him, I couldn’t help but think that Tyson was capable of achieving historic, all-time pound-for-pound greatness. Consider: Louis holds the records for the longest continuous championship reign at 11 years 255 days and for the most consecutive successful title defenses with 25. If Tyson had been able to maintain this form and this level of discipline and motivation, it was not crazy to believe he could have surpassed both records, for Tyson would have been just 32 by the time he exceeded Louis’ longevity mark and would have probably passed Louis’ 25 defenses by year eight of his reign – if not sooner.

But it wasn’t to be. Even Tyson would admit that he didn’t come close to realizing his full potential, yet his record and notoriety was such that he was a first-ballot International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee. His aura was so powerful that he managed to regain most of his invincibility despite the devastating TKO loss to Buster Douglas in 1990 and a four-year prison stint, and even now, more than 16 years after his final official match, some still believe that the 55-year-old Tyson can rise from his easy chair and blast out his share of current heavyweights.

No matter what one may think of his abilities now, it is beyond debate that 35 years ago today, Mike Tyson was “Kid Dynamite,” “Iron Mike,” “Catskill Thunder” and “The Baddest Man on the Planet” all rolled into one overpowering force of fistic nature.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 20 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook and Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE