Evander Holyfield’s battering of Mike Tyson proved again there is nothing certain in boxing

Not that he could have known it then, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt might have been speaking of the state of heavyweight boxing nearly 60 years later when he delivered his first inaugural address on March 4, 1933.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance,” FDR told his fellow Americans on that day as the Great Depression, the four-year financial pandemic that began in August 1929, was on the verge of passing into history.

In the mid- to late-1980s and into the early ’90s, heavyweight boxing’s most fear-inducing terror had a name: Mike Tyson. And the fear the scowling young knockout artist generated was justified, and then some. “Iron Mike” spoke of driving nose bones into opponents’ brains, of breaking their spirit and taking their manhood. Many of his soon-to-be pulverized victims were so afraid of facing him that they were essentially defeated before the bell for the first round rang, in the manner of petrified lambs fully aware they were being led to slaughter.

Tyson’s aura of invincibility, of course, had been cracked if not exactly shattered when he was knocked out in 10 rounds by 42-to-1 longshot Buster Douglas in Tokyo on February 11, 1990, but even that all-time stunner did only so much to lessen the defeated champion’s reputation as the baddest man on the planet. The talented but usually indolent Douglas had trained with uncommon zeal, dedicating the bout to his recently deceased mother, and Tyson had trained with increasingly common disinterest, so accustomed had he become to merely showing up and belting his next designated victim into a stupor and likely visits to the nearest hospital.

On the edge of Tyson’s horizon stood Evander Holyfield, the former undisputed cruiserweight champion who had moved up to heavyweight in the summer of 1988 and was being touted in some quarters as the only plausible threat to a refocused Tyson. But the public at large still found it difficult to accept the possibility that Holyfield might actually defeat Tyson, even after the 1984 Olympic bronze medalist had scored a one-punch, third-round knockout of Douglas on Oct. 25, 1990. Oh, sure, an iron-willed plugger like Holyfield probably could make a decent fight of it for a while, but sooner or later the scariest heavyweight battering ram since the heydays of Rocky Marciano, Sonny Liston and a youthful George Foreman would do unto “The Real Deal” what he had done to Trevor Berbick, Tyrell Biggs, Tony Tubbs, Michael Spinks and so many others. There was no object immovable enough, not even Holyfield, capable of withstanding Tyson’s irresistible force for long. Or was there?

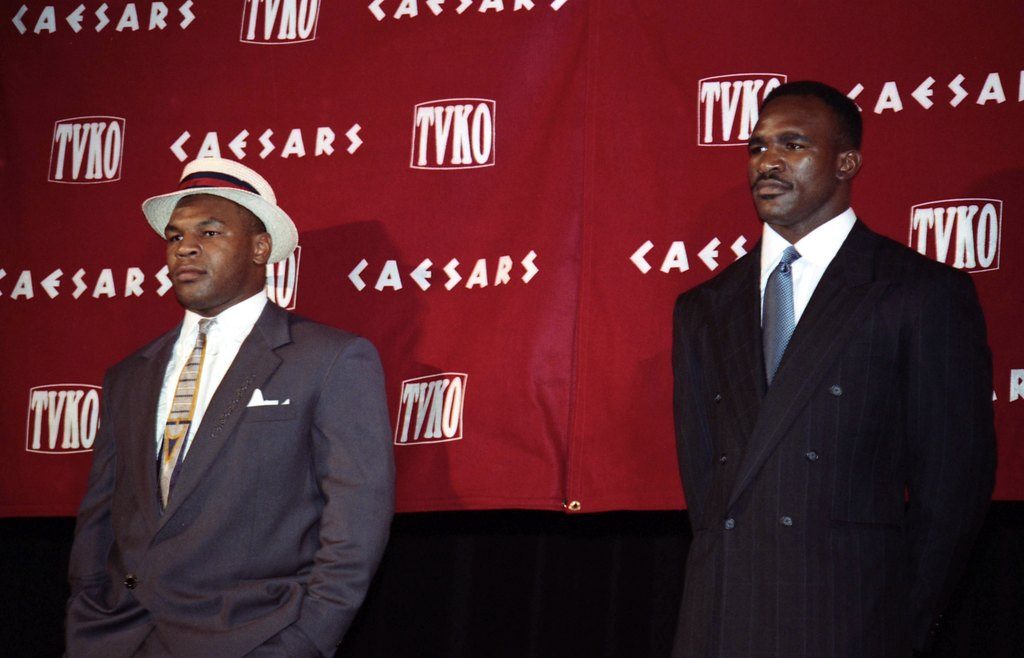

What if… Tyson and Holyfield fought on Nov. 8, 1991? Photo from The Ring archive

The matchup that everyone wanted to see, even if most fight fans suspected they knew what the outcome would be, was scheduled to take place on Nov. 8, 1991. It spoke well of the oddsmakers’ high regard for Holyfield that he was only a 2-1 opening-line underdog, but the wagering gap figured to widen as deep-pocketed backers of Tyson – who had followed the loss to Douglas with first-round stoppages of Henry Tillman and Alex Stewart and two wins over Donovan “Razor” Ruddock, one inside the distance — bet the house on someone they had always regarded, until Douglas, as a sure thing.

But the fight never took place, not on the originally scheduled date. It would remain on hold for five long years. Tyson sustained an injury to his ribcage in training on Oct. 7, forcing a postponement until sometime in January 1992, but whatever new date might have been selected also evaporated like morning dew when Tyson was convicted of raping a teenaged beauty pageant contestant in Indianapolis and was sentenced to a six-year prison term, of which he served three years.

Following his parole, Tyson scraped off as much accumulated ring rust as he could, revealing snippets of his devastating best in blowout victories over Peter McNeeley, Buster Mathis Jr., Frank Bruno and Bruce Seldon. The one-round romp past Seldon gained Tyson the WBA title, which he would attempt to defend in the Nov. 9, 1996, pairing with Holyfield at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand.

Today marks the 25th anniversary of the first Tyson-Holyfield clash, which demonstrated, as did Tyson-Douglas, that those who fail to factor variables into the equation are apt to be reminded that apparent surprises sometimes are not all that surprising. The 30-year-old Tyson who entered the ring that night surely was not all that he once had been, but he nonetheless was a huge 25-1 opening-line choice over Holyfield, 34, just 6-3 in the interim since he was first slated to swap punches with Tyson. Holyfield had appeared sluggish and badly faded in his most recent bout, a fifth-round stoppage of Bobby Czyz on May 10, 1996, in Madison Square Garden.

The fact that the odds against Holyfield had shriveled to 8-1 by fight night was not so much an indication of abiding faith in the two-time former champion as it was bettors figuring that someone with his track record was worth taking a flyer on, even if there wasn’t much likelihood of cashing a winning ticket.

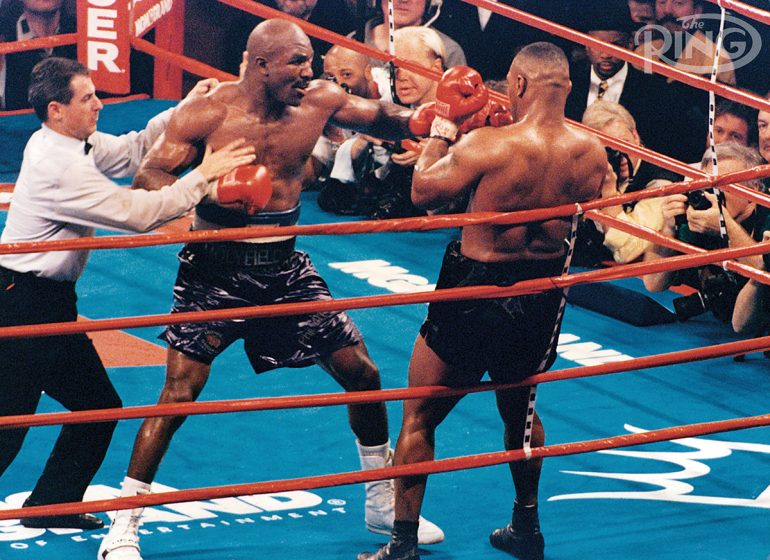

But the blowout Tyson supporters had expected turned out to be a rout of another sort as Holyfield seized control from the outset in capturing a version of the heavyweight crown for a third time, tying Muhammad Ali’s record. Before a sellout crowd of 16,325 and millions of pay-per-view subscribers, Holyfield, who improved to 33-3 with 25 KOs, repeatedly capitalized on an exploitable flaw that his trainer, Don Turner, had detected in Tyson’s attacking style.

“I knew it would end this way,” Turner said after referee Mitch Halpern stepped in to rescue a reeling Tyson (45-2, 39 KOs), who had just absorbed a nine-punch fusillade, 37 seconds into the 11th round. “Tyson never gets countered. Whenever he throws a punch, other guys cover up because they’re afraid to get hit. They let him take all the initiative. Holyfield has enough intestinal fortitude to fight back. That was the deciding factor. Every time Tyson punched, Holyfield would counter him right away.

“Tyson is a very good fighter, but I’ve studied more of his tapes than I have of anyone else. I know everything Mike Tyson is going to do. For instance, Tyson, after throwing a jab, always dips to his left. You can’t miss it. We worked on that move from day one. Check the replays. Every time Tyson did it, Holyfield would come right back and nail him with the straight right and right uppercut.”

Holiday 1996 issue

Through the 10 completed rounds, the extent of Holyfield’s mastery of the moment was reflected in the official scorecards. Judges Dalby Shirley and Jerry Roth had Evander ahead by the same 96-92 margin, but Frederico Vollmer had him winning even wider at 100-93.

No doubt Turner’s attention to detail, and Holyfield’s crisp execution of a well-mapped-out fight plan, contributed to the totality of his long-delayed moment of triumph against his dream foe. But the origins of that moment might trace back more than a decade, to 1984 and a recreation room at the United States Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Ron Borges, then with the Boston Globe, was the only writer of the 48 polled by the Las Vegas Review-Journal who picked Holyfield to win, which gained him instant status as a Nostradamus or Jeane Dixon of pugilistic prognostication. Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy even called the Globe’s sports department asking for Borges’ contact information so he could personally congratulate him.

“I wasn’t really that smart,” Borges told me for a story I did in November 2015. “I picked Evander in nine rounds. He took two rounds longer than I expected.”

Truth be told, Borges’ against-the-grain selection of Holyfield was heavily influenced by what has since become known as “the pool table incident.”

“Oh, sure, there are a lot of people who say that they always knew Holyfield would beat Tyson,” Borges said. “Back then (in 1996), nobody thought Holyfield had a chance. There was a lot of talk after his fight with Czyz that Holyfield was damaged goods and should not even be allowed to fight Tyson. I had a little inside information because I was fairly close to Holyfield during those years. One of the things I knew, dating back to when Holyfield and Tyson were amateurs, was the pool table incident.

“Vinny Pazienza was Tyson’s roommate at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado in 1984. One night they were all playing pool and it was one of those deals where if you lost, you gave up the table. Tyson lost and it was Holyfield’s turn to play. Tyson tried to bully him. Vinny was there and saw the whole thing. Holyfield walked up to Tyson, didn’t say a word and took the cue stick from him. Tyson left the room and nobody saw him for the rest of the night. I always had this image in the back of my mind that Tyson knew if there was one guy he couldn’t intimidate, it was Evander Holyfield.”

As Borges noted, the vote of confidence he gave Holyfield a quarter-century ago was seconded by a number of other observers who came forward to say that they, too, strongly believed the Georgian had the right mindset to take down Tyson not only then, but at whichever point in their respective careers when they might have tangled.

“If that fight had gone off as planned in 1991, it would have been the same outcome as the one five years later,” said trainer Tommy Brooks, who at various times worked with both Tyson and Holyfield. “Evander just had Tyson’s number. Sometimes, that’s just the way it is. Evander had the right style to fight Mike, and he had that incredible mental strength as well.”

Said Nigel Collins, a former editor of The Ring: “Evander Holyfield could have fought Mike Tyson at any time in their careers and would have won 99 times out of 100 because he had such a strong belief in himself. After their first fight, I went to Don Turner’s house to watch the tape. Don commented on what was happening. At one point he told me, `I can tell most fighters how to beat the other guy, but some don’t have the balls to do it. Evander does.’ And that pretty much sums it up.”

For all his presumably superior physical attributes, the foremost being power, where Tyson came up short in comparison to Holyfield was the heart and head, in the estimation of longtime Holyfield cornerman Lou Duva.

“All that chest-thumping Tyson did was an act,” Duva said after Holyfield first slew the figurative giant. “He was trying to make himself believe he couldn’t be beaten. He knows better now. But you know what? Deep down inside, I think he always knew.”

Tyson sent reeling from a right-hand bomb in the 10th. Photo from The Ring archive

Being one of the 47 incorrect pickers of the Tyson-Holyfield I, it now seems reasonable that I and a few other media members in attendance for casual hotel-suite interview session with Holyfield a few days before the fight should have picked up on his confidence level that did not suggest even a scintilla of fear for what he was about to face.

“When Mike went away (to prison), I kind of lost my desire,” he said. “I thought there was nobody out there who really, really, really got me up to fight.

“I don’t think people will truly appreciate me until after I’m gone. That’s when they’ll say, `You know, that Evander Holyfield was a pretty good fighter. He was something special.’ Everyone already believes Tyson is special. They don’t question that he has all this talent. The fighter I get compared to the most is (the late former heavyweight champion) Ezzard Charles, a blue-collar, hard-working guy who is usually thought of as something of an overachiever. Personally, I like being compared to Ezzard Charles. I take it as a compliment. But he couldn’t have accomplished all that he did if he didn’t have something else going for him. The man could fight, and so can I.

“After I won the title from Buster Douglas, a lot of people didn’t give me credit because they thought I beat someone who had been lucky enough to catch Tyson on a bad night. It was like they thought Tyson still was the champion, so they had to knock me and my performance to justify that position. I heard what was being said, but I didn’t let it bother me. There isn’t much that I allow to bother me. Negative comments didn’t make me any less of a champion. I’ve never questioned in my own mind who I am or what I’ve accomplished or what I’m still capable of doing. Everybody says Tyson is the man and he’s going to run over everybody, including me. You know what I say to that? Wonderful. Because nobody can say anything bad when I beat him.”

After he did what he always believed he would do, the usually self-effacing Holyfield smiled and said, “The only difference between Tyson and myself is that he just knocks out people quicker than I do.”

History, including boxing history, is not frequently written in absolutes. Tyson diehards continue to insist that he would have gobsmacked Holyfield had the fight that didn’t happen in 1991 gone off as scheduled. Maybe they’re right, and maybe not. Tyson’s ear-chewing disqualification loss to Holyfield in the do-over, on June 28, 1997, seemingly ensures a higher place than the Brooklyn-born bomber at the table of all-time great heavyweights, but opinions will always vary. During his abbreviated, five- or six-year prime, which might or might not have lasted longer had it not been for his incarceration, Tyson was a force of nature, a human tornado that was a marvel to behold. It all comes down to individual preferences, with some leaning toward Tyson’s explosive detonations when he at least appeared to be unbeatable, vs. Holyfield’s incredible longevity, a 27-year professional run that saw him win some version of the heavyweight title four times, with a fifth belt denied him on an atrociously unjust decision when he took on 7-foot Russian giant Nikolai Valuev.

But regardless of which side of that debate anyone is on, the fact remains that when Holyfield and Tyson finally did get it on for the first time, it was Holyfield who turned in a performance that Long Beach Press-Telegram sports columnist Doug Krikorian described as “Rembrandt artistry as he out-boxed, out-slugged, out-thought and out-gutted” Tyson.

That debate has been raging for 25 years. More than likely, it still will be on Nov. 9, 2046.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.