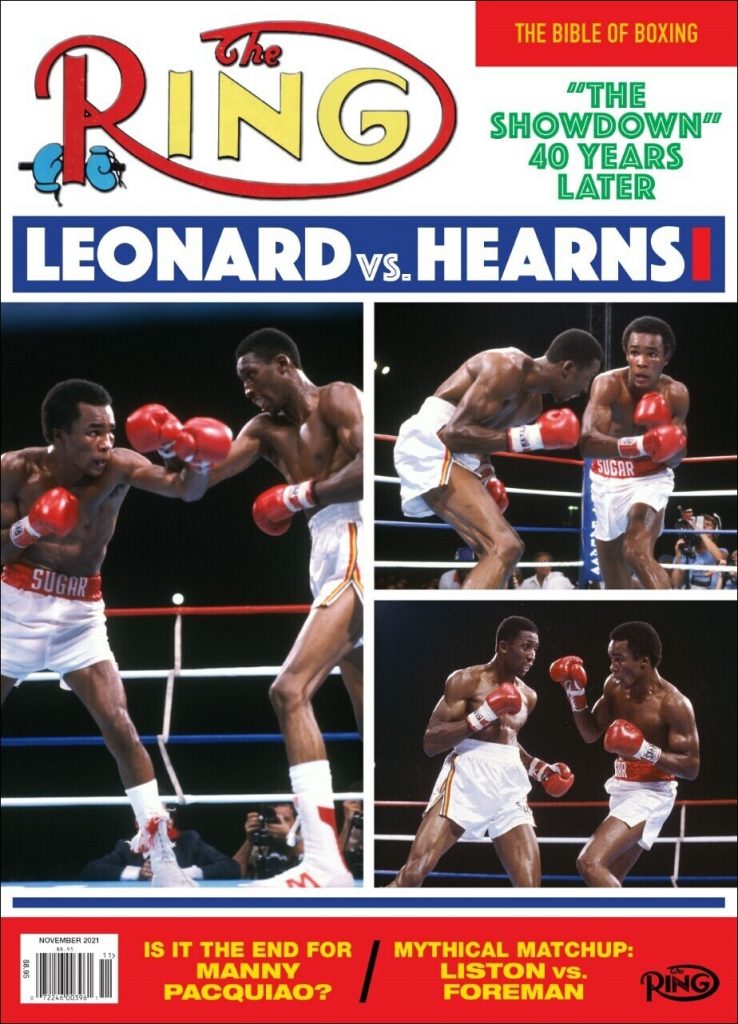

A fan remembers Sugar Ray Leonard vs. Thomas Hearns I

Forty years ago today, Sugar Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns gifted the sports world with a battle whose reality exceeded every expectation. It was an event that featured two elite athletes with contrasting styles and personalities, a fight whose multiple momentum shifts spawned one of the most famous lines ever uttered by a trainer (“you’re blowing it, son, you’re blowing it.”) and one of those magical nights that illustrate why boxing, for all its troubles, remains the most compelling and enduring of sports.

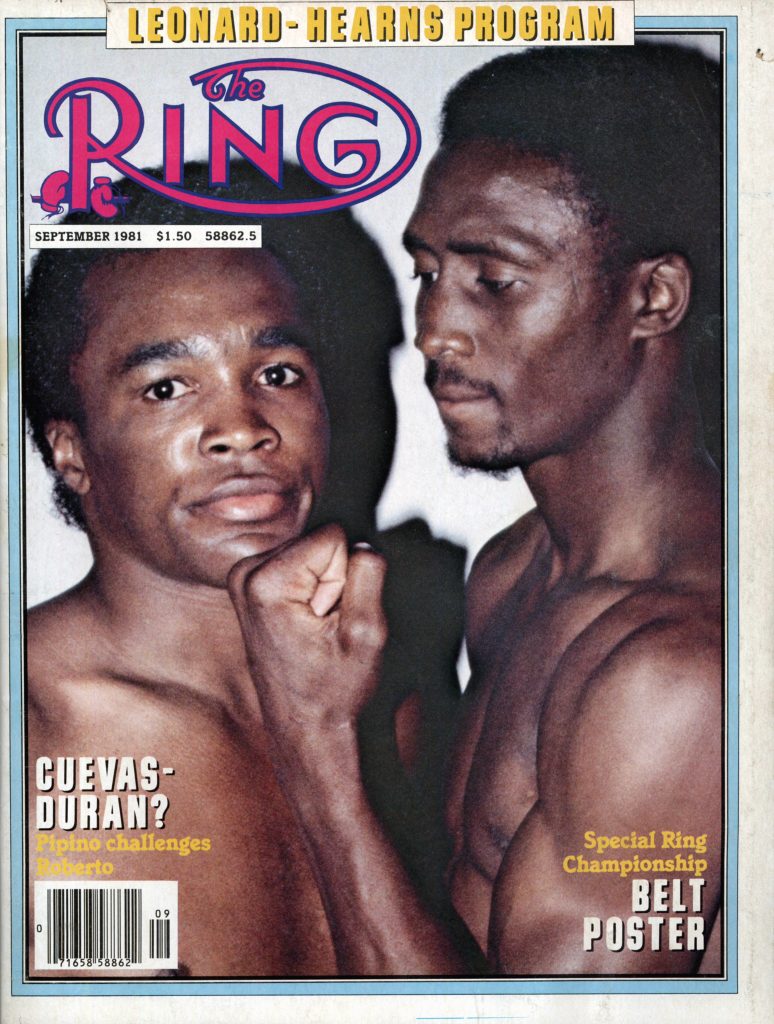

Even now, Leonard-Hearns I remains the standard by which all subsequent fights are measured in terms of timing, staging and execution. It was the most attractive fight that could be made at the time regardless of weight class, and one reason was that it was the sport’s first title unification match since Roberto Duran and Esteban DeJesus united the WBA and WBC lightweight titles in January 1978. Another was that, chronologically speaking, the 25-year-old Leonard (The Ring and WBC welterweight king) was at his positive peak while the 22-year-old Hearns (his WBA counterpart) was a few years away from his.

Thanks to Leonard’s title-regaining eighth-round TKO over Duran, his lone conqueror to date, and his subsequent TKO victories over Larry Bonds and Ayub Kalule, he had fully restored whatever luster he lost in losing to Duran in “The Brawl in Montreal” while also raising his record to 30-1 (21). His magnetic smile and a personality described as “home cooking” by chief second Angelo Dundee made him the natural successor to Muhammad Ali as the face of boxing, but inside the ring he was supremely gifted with lightning-quick fists, masterful footwork, underrated single-shot power, exquisite conditioning, exceptional ring intelligence and a deep reservoir of competitiveness and courage that was graphically unearthed by Duran in their classic first meeting.

Meanwhile, Hearns represented a mortal threat to Leonard’s fistic renaissance; his 6-foot-1 frame was highlighted by a mammoth 78-inch reach that produced piston-like jabs, torrid hooks to the body and one of the most dangerous right hands the welterweight division had ever seen. By learning to lock his elbow and to tightly clench his fist as he punched – tips he learned from chief second Emanuel Steward — the amateur who produced just 12 knockouts in 163 fights started his career with 17 consecutive KO wins and developed into one of the division’s most terrifying punchers.

Hearns destroyed Pipinio Cuevas.

Much of that reputation was formed on August 2, 1980 when he decimated then-WBA titleholder Pipino Cuevas in less than six minutes before a supercharged crowd inside Detroit’s Joe Louis Arena. The opening exchange of hooks essentially decided the fight; although Cuevas’ was launched a split-second earlier, Hearns’ shorter flight path and quicker trigger enabled him to hit the target first and hardest. The sight of the iron-chinned Cuevas staggering backward was all Hearns needed to see, and from that point forward it was one-way traffic. A pair of trademark right crosses left Cuevas on his face, and though he managed to regain his feet, Cuevas’ manager Arturo “Cuyo” Hernandez had seen enough and stopped the fight. Not only did Hearns dethrone Cuevas, he damaged the Mexican’s legacy to the point that he wasn’t elected into the International Boxing Hall of Fame until 2002, 13 years after his retirement and seven years after his first year of eligibility.

Among those at ringside was Leonard, who said in his autobiography “I knew Tommy was good. I didn’t know he was that good.”

“The Hit Man’s” overpowering performance against Cuevas ignited visions of a future title unification fight, first against Duran, then against Leonard after he won the “No Mas” rematch. As fans and media members watched Leonard stop Bonds in March 1981 and Hearns destroy Luis Primera in December 1980 and halt Randy Shields in 12 nearly five months later, they not only observed the action in the ring, they projected how this version of Leonard would have fared against the Hearns they last saw and how this version of Hearns would have performed against the Leonard they last saw. Those feelings were magnified a thousandfold on June 25, 1981 when Leonard and Hearns headlined a closed-circuit card inside the Houston Astrodome. While Hearns easily disposed of ninth-rated Dominican Pablo Baez in four rounds, Leonard had a much tougher time against reigning Ring Magazine and WBA junior middleweight champion Kalule, a Denmark-based Ugandan southpaw who entered the fight with a 36-0 (18) record as well as four successful title defenses. Promoter Bob Arum went as far as to predict a Leonard loss, but while Kalule more than held his own and even stunned Leonard, Leonard scored the fight’s only knockdown at the end of Round 9, and because the count – and the stoppage – extended beyond the bell, the official time was 3:06.

With that, all roadblocks to Leonard versus Hearns were removed.

Although I was 16 at the time of “The Showdown,” I had already invested seven-and-a-half years of my life into following the sport, and after having watched the rebroadcast of Hearns-Baez and Leonard-Kalule on NBC’s “SportsWorld” series on July 5, I concluded that Hearns would prevail over Leonard on September 16. First, Leonard would be facing deficits in height (four inches) and especially reach (seven-and-a-half inches), a dynamic that would allow Hearns to dictate distance while also forcing Leonard to fight through Hearns’ ramrod jabs and lethal right crosses just to get in range to land his own punches. Second, although Hearns lacked Leonard’s mobility, his hand speed was at least comparable, if not equal. Third, while Leonard was the better all-around fighter with a deeper pedigree in championship fights, Hearns was capable of ending a fight with a single punch and he proved against Clyde Gray (KO 10) and Shields (KO 12) that he could carry his power into the later stages of a match. Finally, Hearns still wore the cloak of invincibility that comes with being undefeated and with having scored 30 knockouts in 32 victories, including a TKO win over common opponent Shields, who went 10 competitive rounds with Leonard before losing a decision in October 1978. Leonard opened as an 8-to-5 favorite, but a late rush of money from “The Hit Man’s” Detroit devotees swung the odds to 7-to-5 for Hearns.

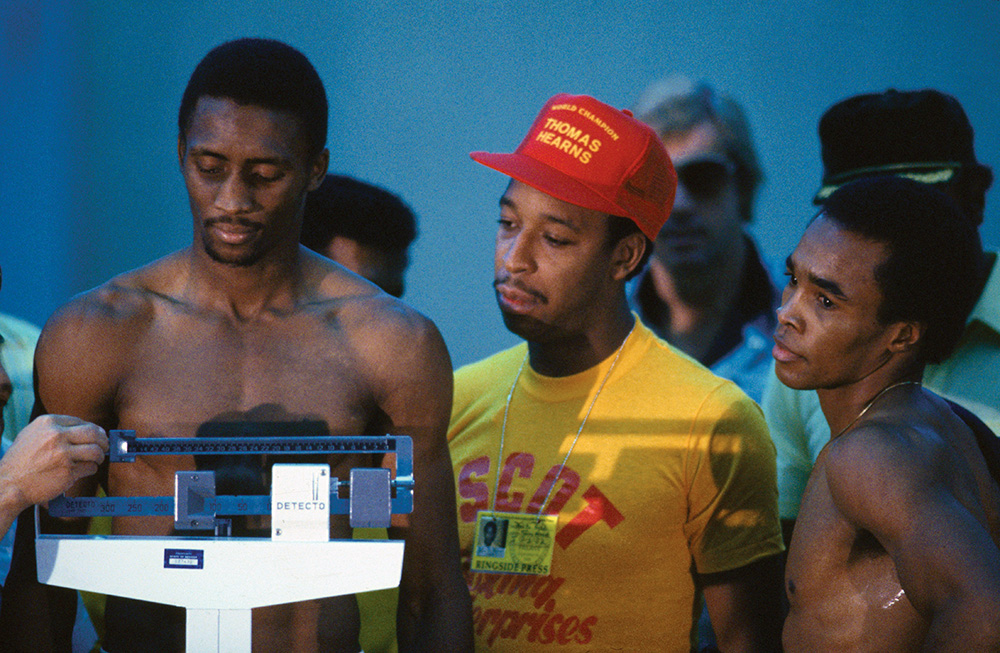

Because none of the 298 closed circuit theaters were located anywhere near Friendly, West Virginia – and because the bout was staged in the waning hours of Wednesday night on the East Coast – this Sistersville High School sophomore who had to go to school the following morning could not see the fight live; I had to wait until ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” aired a full-fight replay. I also missed the weigh-in staged at 8 a.m. the day of the match, and while Leonard scaled a marvelously conditioned 146, Hearns made news by weighing a surprisingly light 145, his lowest weight since his three-round destruction of Bruce Curry in June 1979.

Steward attributed this to Hearns’ increasing defiance of his chief second’s authority. According to Steward’s account in Dave Anderson’s “In the Corner,” Hearns went against the trainer’s orders in sparring six rounds two days before the fight (Steward wanted sparring to end one day earlier), then not eating the evening before the match as Steward recommended.

“The next morning I’m expecting to see a big welterweight, but Tommy looks like a skinny welterweight with a sunken-in face,” Steward told Anderson. “For our previous few fights, the script was for Tommy to just make the 147-pound welterweight limit…but now he’s 145 at the weigh-in for what was the biggest fight of his career at that time. That’s when I learned about the importance of nutrients.”

“He looked like a famine victim from Africa,” Leonard wrote in his autobiography. “I am going to kick his a**, I thought. I glanced at Angelo and Janks (Morton). I could tell they felt the same way.”

Hearns came in well below the welterweight limit, but did the decision to go light cost him?

Although Leonard’s physique appeared perfectly conditioned, he carried a secret injury into the Caesars Palace ring. Approximately two weeks before the bout, sparring partner Odell Hadley accidently struck Leonard’s left eye with his elbow and while the eye swelled the following morning, the shiner disappeared quickly enough to avoid detection.

As they climbed into the ring, each man wore robes with a specific message. Hearns’ read “Winner Take All” while Leonard’s bore the word “Deliverance.”

“In the dictionary, the definition is ‘liberation, salvation, rescue.’” Leonard wrote. “That summed it up. Taking on Tommy Hearns was my chance to acquire the respect that I was being denied by a number of the veteran boxing writers who still saw me as a fighter created by television what had yet to defeat a star opponent. In their view Benitez was not in that class. Duran was, but they argued that the outcome in New Orleans was more about him surrendering than my causing him to surrender. Conversely, they saw Tommy, with his devastating power, as a legitimate fighter who earned his way to the top without being coddled by (ABC broadcaster Howard) Cosell. The commercials I appeared in reinforced this point of view. I sold soda. Real fighters didn’t sell soda.”

The atmosphere that enveloped the outdoor arena next to Caesars Palace’s Sports Pavilion was supercharged with excitement and anticipation. The sellout crowd of 23,618 paid between $50 and $500 to witness the event, and although the sun had already set, the heat and humidity remained stifling and would be even more so for Hearns and Leonard under the TV lights. A coin flip determined that Hearns would enter first but be introduced last, and when he took off his robe his upper body appeared more chiseled than was the case at the weigh-in. Leonard was stunned by what he saw.

“The Tommy Hearns I saw when I entered the ring around 7:30 p.m. was not the same fighter from the morning,” he wrote. “He looked as if somebody had pumped him up with air. He clearly had spent the whole afternoon hydrating himself. Any illusions of an early knockout on my part were put aside. Caught off guard, I needed to do something, and quickly.”

It was at this point he called a psychological audible.

“I bounced up and down as the ref, Davey Pearl, issued his instructions,” he wrote. “By not staying flat on my feet, Tommy was unable to fully appreciate the height difference between us, which was at least three inches. It was no secret he was taller, but I hope to put a little doubt in his mind.” Also, Leonard avoided looking directly into Hearns’ eyes, sparing himself the possibility of being negatively affected by the “Hit Man’s” withering stare.

The fight began with Leonard on the move, circling left and right as Hearns stalked menacingly behind probing jabs that intentionally fell short of the target. Despite Hearns’ rehydrated state, Leonard still appeared to be the better proportioned athlete; his upper body was larger and more sculpted while Hearns’ physique was long, lean and wiry. That said, some of history’s most dangerous hitters were built like Hearns, and the record showed his knowledge of leverage was beyond argument.

Both men were in look-and-see mode but Hearns was at least trying to force the fight, a dynamic that moved Dr. Ferdie Pacheco – a longtime associate of Dundee’s but who was acting as analyst on the closed-circuit broadcast with blow-by-blow man Don Dunphy – to say “he’s gotta do some fighting if he’s going to win some points; he can’t just be running this whole first round.” Leonard wanted to turn this war into a thinking-man’s fight, where strategy and acumen would hold sway, while Hearns preferred a gunfight because he believed his bullets were of higher caliber. Hearns’ fearsome crosses whizzed by Leonard’s chin but as the round continued his jabs were connecting with force.

At the end of Round 1– a round Hearns won on all scorecards – Leonard disdainfully pushed his open right glove against the side of Hearns’ face, a disrespectful act that prompted Hearns to fire a right that barely, but intentionally, missed its target. Not one to be one-upped by anyone, even non-verbally, Leonard answered Hearns’ gesture by grabbing the rope with his right hand, sticking out his tongue and breaking out into a faux-wobble before walking back to his corner.

The pattern established in Round 1 continued in Round 2, with the only difference being Leonard waving his right glove in semi-showboat fashion midway through the stanza and fighting with his left hand dangerously low at times, as if he wanted Hearns to fire the big right. Moments later, Hearns did just that, and the fight might have ended then and there had Leonard not rolled away from the blow. As the round neared its end, Leonard’s movement had gradually but perceptively slowed and he projected an increased willingness to engage – but engage on his terms. Although Leonard connected with a hook in the final seconds, Hearns still swept the round on all scorecards.

Hearns’ huge advantages in height and reach kept Leonard from getting off for long periods. (Photo by Dirck Halstead/Liaison)

Leonard remained on the move in Round 3, but was more offensive-minded as he jabbed to Hearns’ body and was more willing to initiate exchanges. That said, Leonard remained wary of the big right; while propped against the ropes, Leonard deftly ducked under it and pivoted to ring center. Hearns, seeing this, flashed a grin that seemed to say, “you may have avoided that one, but I almost got you – and more are coming.”

So far, the fight was more chess match than raw combat; one could almost see the wheels whizzing inside their heads as they executed moves and counter-moves with dizzying speed, and every so often the crowd roared whenever either fighter landed a head-snapping punch. Yes, it was a thinking man’s fight, but it was a well-received thinking-man’s fight.

In the closing minute of the third, Leonard deked with the right hand to set up a one-two to the jaw, then spun away from Hearns’ counter, a series of moves that brought a wry smile from Hearns. The gap between them was the narrowest yet, and, for the first time in the fight, Leonard fought with boldness – respectful boldness – but boldness nevertheless. The round’s final moments saw them up the ante even more as they traded with abandon and got in the most dangerous blows of the night thus far. This time, the judges were split; Duane Ford and Chuck Minker favored Leonard while Lou Tabat awarded Hearns his third consecutive round.

The fourth commenced with both men standing flat-footed and firing straight, spearing punches that connected with classy crispness. Hearns’ industriousness earned him the advantage throughout the first two minutes, but with Dundee shouting “it’s all you,” Leonard landed a stiff counter right at the start of the final minute that Hearns absorbed unflinchingly. The final 30 seconds of the fourth, like the closing moments of the third, produced compelling two-way action, but thanks to Hearns connecting with a series of crosses, all three jurists gave “The Hit Man” the session.

Following a fifth round thoroughly dominated by Hearns’ excellent long-range boxing, the WBA titleholder forged a commanding lead on all three scorecards – 50-45 (Tabat) and 49-46 (Ford and Minker). He was the effective aggressor who landed more often and more powerfully with better consistency, who proved he could jab with the master jabber and defend with the slicker defender, and was the better ring general as he made Leonard react to him instead of the other way around. Pacheco worried that Leonard was showing too much respect and giving too many rounds away and Dunphy agreed Leonard had dug himself a deep mathematical and strategic hole. While Leonard could still win on points, his window was rapidly shrinking.

With Dundee shouting “speed, Ray, speed” time and again, it was Hearns who dominated the first two minutes of the sixth with piercing jabs and accurate power shots, prompting Dunphy and Pacheco to utter statements that were both discouraging and predictive.

Dunphy: “Leonard hasn’t thrown a real good combination yet in the whole fight.”

Pacheco: “Midway in the round, and still Leonard has shown no signs of offensive action.”

Dunphy: “He (Leonard) may be hoping that one punch will turn it his way, which is a possibility, but…”

Pacheco: “…it’s always possible, but not probable.”

Just 13 seconds later, Leonard found that one punch Dunphy said he needed to violently swing the fight his way. A beautifully targeted 45-degree hook to the jaw suddenly turned Hearns’ legs to jelly, and with that single punch Hearns was transformed from predator to prey and Leonard from prey to predator. As the crowd shrieked with surprise, Leonard pursued Hearns with an animalistic fury while Hearns futilely tried to convince his opponent he was unhurt by flashing a grin and sticking out his mouthpiece. Hearns created a more compelling case by landing several power shots, but with 26 seconds left Leonard’s knifing hook to the ribs nearly folded Hearns in half. This time Hearns didn’t even try to conceal his pain, but his response showed that his survival instinct leaned more toward “fight” than “flight.” That instinct allowed him to survive the round, but, for the first time in his pro career, Hearns was confronted with the very real possibility of not just defeat, but a knockout defeat.

The emboldened Leonard opened the seventh with several hard, head-snapping jabs, and he felt comfortable enough to engage Hearns in the trenches. With a minute gone, Leonard landed another hook to the ribs that caused Hearns to reflexively fold inward, and that hook set up a sizzling right uppercut/left hook/left hook/right uppercut that buckled Hearns’ legs, prompting Dundee to switch from “Speed, Ray, speed” to “Body! Body!” Once again, Leonard listened well as he connected with a crunching hook to the flanks, and soon Hearns was tottering about the ring with his right elbow pressed tightly against his side. Unfortunately for Hearns, his survival kit didn’t yet include the ability to clinch or to stall for time; instead, he did his best to fight through the fog – and, at times, the fog was winning.

With 23 seconds remaining in a hellish seventh, Hearns lashed out with a desperate hook to the belly, then missed wildly with a hook over the top. Then, as if a light bulb went off in his brain, Hearns finally slapped on a clinch and waited for Pearl to separate them, a maneuver that burned off enough precious seconds to grant him the privilege of a 60-second pause.

With 23 seconds remaining in a hellish seventh, Hearns lashed out with a desperate hook to the belly, then missed wildly with a hook over the top. Then, as if a light bulb went off in his brain, Hearns finally slapped on a clinch and waited for Pearl to separate them, a maneuver that burned off enough precious seconds to grant him the privilege of a 60-second pause.

Hearns’ stuttering gait as he walked toward his corner and the way he plopped onto his stool and sloppily spat out his mouthpiece was almost too much for Steward to bear. But before acting on impulse he needed input from his fighter.

“I’m gonna stop the fight,” Steward told Hearns.

“No, don’t stop it,” Hearns replied without hesitation.

“But you ain’t punching, man,” Steward retorted. “I’m gonna have to stop it if you don’t punch!”

The difference between a good trainer and a great one is that the great ones offer specific courses of action, especially when their charges are under duress. And one difference between a good fighter and a great one is possessing enough versatility to change course. For Hearns, that meant a return to his stylistic roots of sticking, moving and scoring, a blueprint Steward called “leg boxing.”

Meanwhile, Leonard had to confront his own crisis; the state of the left eye injury caused by Hadley in sparring. It took less than three rounds for Hearns’ stinging jabs for swelling to sprout, but by this point it had worsened to the point that Leonard’s sight was starting to be compromised.

Two other factors added to their shared suffering: The suffocating heat and humidity as well as the mental stress that comes with elite-level competition whose outcome would result in life-changing, legacy-shaping consequences. This was the environment under which Leonard and Hearns operated — and the fight hadn’t yet reached its scheduled halfway point.

Acting on Steward’s contention that if he kept himself together that he would go on to win the fight, Hearns started the eighth on the move and working the stick. Hearns’ dual-directional fluidity was shocking given the state of his legs just 60 seconds earlier, and Leonard’s stalking revived memories of the opening rounds when Leonard was the mover and Hearns was the pursuer. Hearns even threw in some hand and shoulder feints and the flat-footed Leonard, perhaps weary from the effort he expended in rounds six and seven, lacked the energy to cut off Hearns’ escape routes.

Hearns’ momentum and confidence grew with every passing second, especially after he successfully absorbed a pair of looping overhand rights with relative aplomb. While Hearns lost the eighth on two scorecards (Ford and Tabat), Minker rewarded “The Hit Man’s” superior ring generalship with a 10-9 score.

“You’re back ahead on points,” a much calmer Steward told Hearns, and he was right – through eight rounds Hearns was up 77-75 on Tabat and Minker’s scorecards while Ford had the fight even at 76-76. In the other corner, Dundee asked, “you feelin’ all right now?,” suggesting that the eighth indeed was a recovery round.

For Hearns, any hint of fragility and uncertainty attached to his long-range boxing in Round 8 disappeared in Round 9. His legs had more bounce and his punches had more snap; if Hearns looked like a man who hadn’t ridden a bike since childhood in the eighth, the ninth saw him assume the look of that same man with fully restored muscle memory. Meanwhile, Leonard was always a step behind and he struggled to find opportunities to let his hands go. Because those opportunities were too few and far between, Leonard lost the ninth on all scorecards.

Hearns’ superb boxing continued in the 10th, 11th and 12th, and with the exception of a 10-10 score submitted by Tabat, the WBA champion swept the scorecards to build leads of four (Ford), five (Tabat) and seven points (Minker). At this point, Dundee, who had been businesslike throughout most of the fight, decided this was the right time to amp up the urgency.

“Let’s go, Ray, you’ve only got nine minutes,” he declared. “You’re blowin’ it now, son, you’re blowin’ it. We need to fire; you’re not firin’. Ray, we gotta separate the men from the boys, now; you’re blowin’ it.”

Then, just before heading down the steps, Dundee ducked his head back inside the ring and delivered a final message: “You’ve got to be quicker; you’ve got to take it away from him, OK? Speed!”

“I was losing that fight against Tommy,” Leonard wrote in the November 2021 issue of The Ring. “A fighter knows when they’re losing and they know they have to pick it up. It honestly felt like it was 100 degrees in that ring; my left eye was closing, Tommy’s boxing me. He showed me talent that we didn’t think he possessed – at least I didn’t. In that position you have to bring up that extra hidden reservoir of strength from your gut. You have to believe in yourself, and I just reached down. Not everyone can do it, but I wanted to win. I never lost hope and I never gave up.”

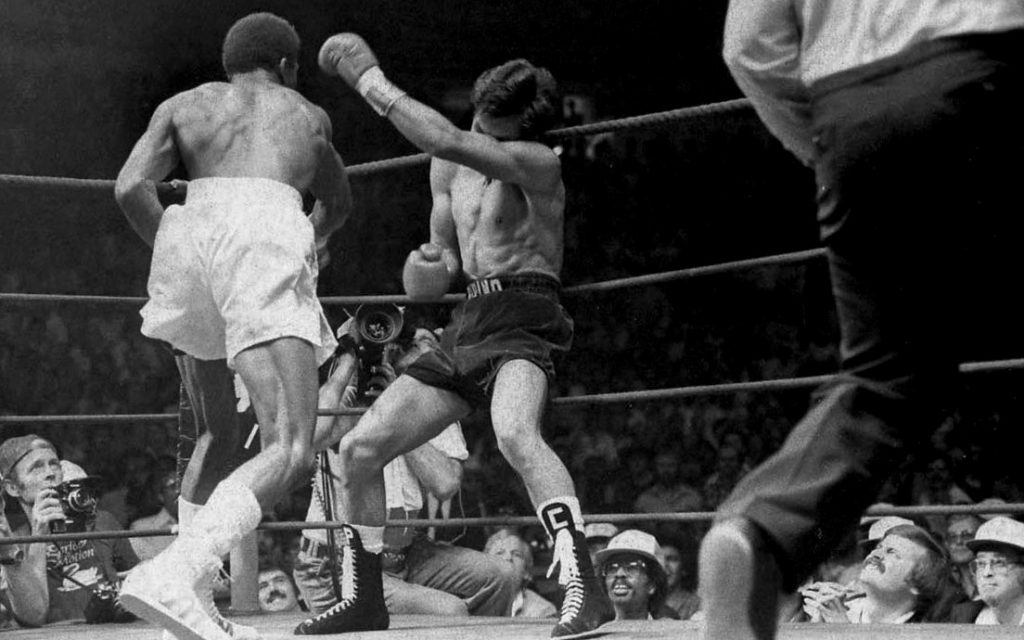

Even with Dundee’s pep talk ringing in his ears, and even though Leonard himself was aware of his circumstance, Hearns still controlled the first half of the round. But then, with 1:28 remaining, Leonard connected with a straight right that caught the tip of Hearns’ chin, a blow whose effects clouded his eyes and weakened his legs. Presented with the break he so desperately needed, Leonard did as Dundee commanded; he fired his fists and he began to separate himself from Hearns while also hoping to separate Hearns from his senses.

A ferocious attack by Sugar Ray changed both the course of the fight and welterweight history. (Photo by Dirck Halstead/Liaison)

Leonard’s explosive salvo struck every available target, and its rapidity forced Hearns to seek refuge along the ropes. The stricken Hearns fell through the middle strands of rope, prompting Pearl to wave his hand and command Hearns to “get up.” Once he did, he managed to evade any further fire for another 35 seconds before a flush left-right to the chin sent him reeling toward the ropes. Leonard continued to punch away at the fleeing Hearns, and with just six seconds remaining Hearns’ body folded nearly in half and fell through the same set of strands. Again, Pearl motioned for Hearns to rise, but then changed his mind and began to count. Hearns straightened up at “three” and the bell sounded a split-second after Pearl tolled “nine” and motioned for the fighters to continue.

All three judges credited Leonard with a 10-8 score, cutting Hearns’ leads to two (Ford), three (Tabat) and four (Minker), margins that infuriated observers who believed Leonard merited 10-8 scores for his dominance in rounds six and seven, which, had they been applied, would have had Leonard even on Ford’s card, trailing by one on Tabat’s card and behind by two on Minker’s. The high-profile nature of Leonard-Hearns I served as a watershed moment in terms of opening the door to 10-8 scores without a knockdown, and although that scenario remains extremely rare 40 years later, it is no longer dismissed out of hand.

Entering Round 14, Leonard and Hearns were engaged in two separate races; Leonard against the clock and Hearns against his weakened body. If Hearns could keep his feet for six more minutes, the worst that could happen to him was a majority decision victory, and even if Leonard scored one knockdown in the final two rounds, he and Leonard would retain their belts with a split draw. But Leonard’s titanic 13th violently swung the pendulum in his direction, and his superlative finishing skills all but guaranteed a positive outcome, whether it be scoring a second knockdown that would give him the extra point he needed to avoid the draw or the TKO that would make him an undisputed champion.

The start of the 14th was an accelerated version of rounds 9-12, with Hearns moving and punching with increased vigor and Leonard marching in with a sharp eye on landing another smart bomb on his opponent’s jaw. Hearns managed to survive the first 70 seconds, but a glancing overhand right to the point of the chin was enough to short-circuit Hearns’ legs. Leonard raised both arms in triumph as Hearns reeled along the ropes because, to him, the fight was all but over. When Pearl didn’t intervene, Leonard moved in with fists flying, but still found enough time to glance at Pearl and beckon him to move in with his right glove. Again, Pearl held his powder, allowing Hearns the latitude to ride out the storm.

Hearns did just that, but shortly after the midway point, Leonard positioned Hearns near the neutral corner pad and cranked a pair of wicked hooks to the ribs followed by a flush right to the jaw that caused Hearns to slump into the ropes. This time Pearl chose to intervene, and at the 1:45 mark of Round 14, Sugar Ray Leonard became the one and only welterweight champion of the world.

“I never had a doubt about stopping it,” Pearl said after the fight. “All I saw was Leonard’s fists hitting him in the head. (Hearns is) a 22-year-old man, and I didn’t want to see him get seriously injured.” As for Leonard’s injury, Pearl felt the orb would have been completely closed by the end of the 14th and “he was going to have to fight the last round one-eyed,” but he would have granted Leonard the opportunity to finish the fight.

While Hearns suffered his first professional defeat on the biggest of stages, fair-minded people felt he didn’t deserve the full sting that comes with defeat.

“Tommy Hearns was clearly not disgraced in the fight,” said Larry Merchant in HBO’s “Legendary Nights” episode that chronicled Leonard-Hearns I. “He (not only) raised the level of his game, he also raised the level of Sugar Ray Leonard’s game.”

“One of us came out victorious, but, still, I say in my book, we both are still champions,” Leonard declared in the post-fight press conference.

Ralph Wiley, the author of “Serenity: A Boxing Memoir,” provided a succinct summation of his historic bout.

“Leonard lost an eye, Hearns lost his consciousness, but they both gained immortality.”

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 20 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook or Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).

The latest issue of The Ring celebrates the 40th anniversary of “The Showdown.” Buy it today from The Ring Shop: