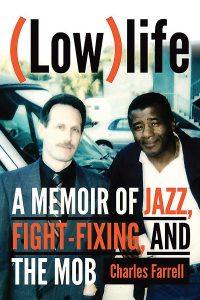

Book review: (Low)life: A Memoir of Jazz, fight-Fixing, and the Mob

Charles Farrell isn’t looking to make friends with his book (Low)life: A Memoir of Jazz, Fight-Fixing, and The Mob. He might even make some enemies if he hasn’t already.

That’s never been a concern for the New Englander, and the result is a fascinating tale that may not be the book for the diehard boxing fan who wants the sport in the pages from start to finish, especially those who aren’t prepared to see another side of the business. But for those wanting to read about an incredible life and the stories that made up that life, stay tuned.

“It’s a memoir,” said Farrell. “I kept telling my publishers (Hamilcar Publications), ‘Look, I know you guys focus on boxing and, in a sense, it’s the most insider boxing book you’ll ever read because it talks about the boxing business. But it’s not a boxing book, and there are gonna be a lot of people who are disappointed and there are also gonna be a lot of people who are disappointed that there’s so much fight fixing that goes on. Even if you love boxing for boxing, the more you know about it, the more interesting it gets. So, all of the stuff I was involved in, to me, makes boxing more interesting, not less interesting. But I can see where people are disappointed.”

“It’s a memoir,” said Farrell. “I kept telling my publishers (Hamilcar Publications), ‘Look, I know you guys focus on boxing and, in a sense, it’s the most insider boxing book you’ll ever read because it talks about the boxing business. But it’s not a boxing book, and there are gonna be a lot of people who are disappointed and there are also gonna be a lot of people who are disappointed that there’s so much fight fixing that goes on. Even if you love boxing for boxing, the more you know about it, the more interesting it gets. So, all of the stuff I was involved in, to me, makes boxing more interesting, not less interesting. But I can see where people are disappointed.”

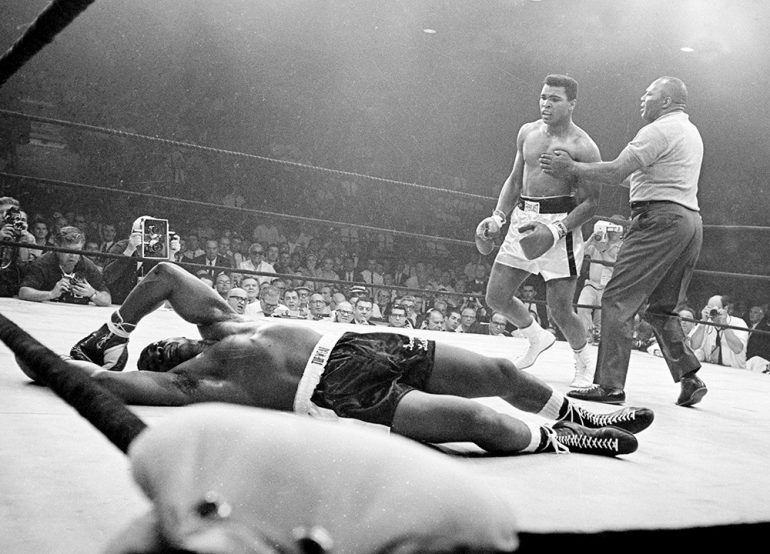

Fight fixing is the tagline of the title and it’s the part of the book that will certainly draw the most attention and heat, particularly Farrell’s assertion that the two bouts between Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston weren’t on the level.

“The thing that gets people most upset is the Liston-Ali fixes,” said Farrell. “People are furious about that, and they say to me, ‘You’ve got no proof.’ Yeah, because these guys were good at what they did. Ali could have beaten Liston and I’ll say, look, I’m not saying anything about Ali as a fighter. He was a great, great fighter. No question he’s a great fighter. And he didn’t know the fights were fixed. You never tell the winner. The thing is, if those fights are fixed, it ruins the image of Ali as an icon. But what I always say is, he was gonna be the champion anyway, no matter what. He was gonna be a great champion.

Mobsters like Frankie Carbo helped make prize fighting the “Red Light District” of sports, but Farrell says they knew boxing a lot better than those who run it today. Photo from The Ring Magazine archive

“But it’s Boxing 101,” he continues. “It’s the smartest score you can possibly make. And it was made by guys who were real boxing guys. Frankie Carbo was a real boxing guy. These guys knew much more than anybody around today. And they’re not thinking in terms of history or romance or glory or any of that nonsense. They’re all adults. They saw a big, big score that was right there for them, and they took it and then they did it again.”

It’s incendiary stuff for sure, along with the alleged fixes Farrell made over his years as a manager. But why would boxing be called the Red Light District of sports if there wasn’t this sordid side to it? So, while you can choose to believe or not believe what Farrell has written, the fact remains that it does exist in some way, shape or form. That’s unfortunate, especially for those who take everything they see in the sport at face value.

“Sure,” said Farrell. “But that’s like saying, when you wrote that there’s no Santa Claus, that there’s no Easter Bunny, you ruined a lot of people’s dreams. Well yeah, but there’s a point when you have to grow up. And I’m thinking, okay, this is a book, in part, about the boxing business, and I’m not gonna sugar coat it, I’m not gonna play games with it, and I’m not even against it. My argument is that fight fixing is good, not bad. I thought, let me write a really honest book about boxing. The more you know about boxing, the more interesting it gets, the more compelling it gets. And if people don’t like it, they don’t like it. Or they can say, he’s making all this up. If that’s what you want to believe, go ahead, it’s okay.”

That part of the book may very well be its selling point, but if that’s the entire focus, then that’s unfortunate, because reading about Farrell’s life in the music business as a jazz pianist is just as compelling as the boxing material, at times even more so. But what is the dirtier business?

“They’re very close, but the guys in the boxing business are much, much tougher, and much more dangerous,” he laughs.

Farrell still practices piano every day, keeping his chops up even if he’s only casually looking at a comeback to the music world.

“It’s always the same,” he said of his daily routine on the piano. “Up and down. But it’s good for me. It keeps me disciplined; it gives me something that I actually know how to do. It’s important for me to do it.”

As for that triumphant return, he laughs.

“Every decade or so I consider it. We’ll see what happens. I play very difficult music and it doesn’t have a commercial audience at all. It never will, and I know that.”

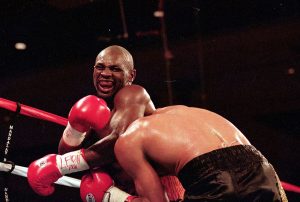

Boxing still has a commercial audience, albeit a shrinking one, but Farrell, who has written extensively for several publications over the years, has left the managerial world behind. He had a good run, working with the likes of Leon Spinks, Mitch Green, Freddie Norwood, and Tyrone Booze, to name a few, and while the latter two names may only ring a bell to diehard fans or those of a certain age, Farrell’s stories of his time with them comprise some of the most compelling material in the book. Of course, it’s material that could be missed if focusing solely on the more sensational aspects of (Low)life.

Freddie Norwood, on his way to outpointing Juan Manuel Marquez in 1999, is one of the fighters Farrell managed and one of the most avoided boxers of the past 30 years. Photo by Jed Jacobsohn / Allsport / GettyImages

“They could miss that,” he said. “But one of the things I was trying to point out in the book is that if fight fixing is part of the business, so is the way that dangerous fighters like Norwood are avoided. He’s a perfect case in point and that’s part of the business, too. Here’s a guy who, for a short time in the 1990s, may have been the best fighter in the world. He was certainly the best fighter in his division, but I couldn’t give him away. That’s part of the business. People don’t understand. It’s a 24-hour-a-day job and with fighters who are difficult to deal with…Norwood, I liked him a lot but he was very difficult because he had never gotten a break of any sort. So, he’s a little bit paranoid, and you gotta keep him razor sharp all the time. If he’s on his own, he’s gonna lose that edge. And he’s fighting this establishment that he can’t beat.”

Norwood never became a breakthrough star, even though he did win the WBA featherweight title twice and defeated Juan Manuel Marquez in 1999. Booze was another fighter who just couldn’t get break or win the big one – sometimes both – but he also picked up a WBO title at cruiserweight in 1992. He lost it four months later but, as they say, that’s boxing.

So, what is Farrell’s relationship with boxing in 2021?

“The same complex one it’s always been,” he said. “I love boxing.”

Farrell begins to talk about how few in the power positions of the sport know the game, but then he stops to correct himself.

“There are guys like Eddie Hearn,” he said. “Eddie Hearn knows boxing. I think a lot of Eddie Hearn. I think he understands the mechanics of it, I think he actually pays attention to who the fighters are, he understands how to market. He understands regional boxing, which almost no promoter does.”

And beyond the Matchroom Boxing boss?

Farrell thinks boxing has potential if the young fighters and the fans can be re-educated to accept losses as part of the sport.

“On a whole, boxing is marketed in a way that makes it almost impossible to have great fights,” Farrell said. “Right now, the smartest thing I think that people in the boxing business could do is to re-educate fans, allowing them to understand that losing a fight doesn’t hurt your marketability if you’re fighting a really good fighter and you’re in a great fight. In (the 130-to-140-pound divisions), there are probably seven to eight guys, maybe more, who are all on the verge of being elite fighters. And most of them are undefeated. And they could all fight each other and they would be great, great fights, and none of them would win all of them and none of them would lose all of them. And you’d have ten years of great fights ahead because these guys are all either just approaching their prime or they’re in their prime. And they would make tons of money and you’d have great fights. And yet, because nobody wants to jeopardize their zero, and no promoters want to risk losing their cash cow, lucrative fights don’t happen.”

That’s boxing. And often, the truth hurts.

“Everybody in the business knows what I’m saying is the truth,” said Farrell. “Everybody. I think they feel that it (the book) will ruin the business in some way, but of course it doesn’t hurt the business at all. Boxing’s always gonna be the same, and there’s nothing you can do to ruin it. And of course, I don’t give anybody up. That’s important that I don’t sell anybody out. But I think people have this romanticized notion of what is supposed to be.”

For more information on (Low)life: A Memoir of Jazz, Fight-Fixing, and The Mob, visit https://hamilcarpubs.com/books/lowlife-a-memoir-of-jazz-fight-fixing-and-the-mob/