Muhammad Ali-Jerry Quarry I: Half a century on from the return of the champion

Fifty years ago today, Muhammad Ali emerged from a three-and-a-half year exile to begin his quest to regain the heavyweight championship that was stripped from him for his refusal to serve in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. At the time he involuntarily left the squared circle, Ali was arguably sport’s most polarizing figure but as sentiment turned against the war, the public view of Ali was shifting from an athletically gifted loudmouth to a political and social symbol whose influence transcended race, ideology, faith and geography.

Numerous attempts were made to restore Ali’s license, and it was ironic that the breakthrough occurred in Georgia, the heart of the Deep South. While Georgia had no statewide athletic commission, individual municipalities within the state did — including Atlanta. Thanks to the efforts of Sen. Leroy Johnson, an African-American, and Sam Massell, Atlanta’s first white Jewish mayor, Ali was granted a license. On September 15, 1970 — four days after Ali signed to fight Jerry Quarry — Federal Judge Walter R. Mansfield ruled that Ali should be granted a boxing license in New York.

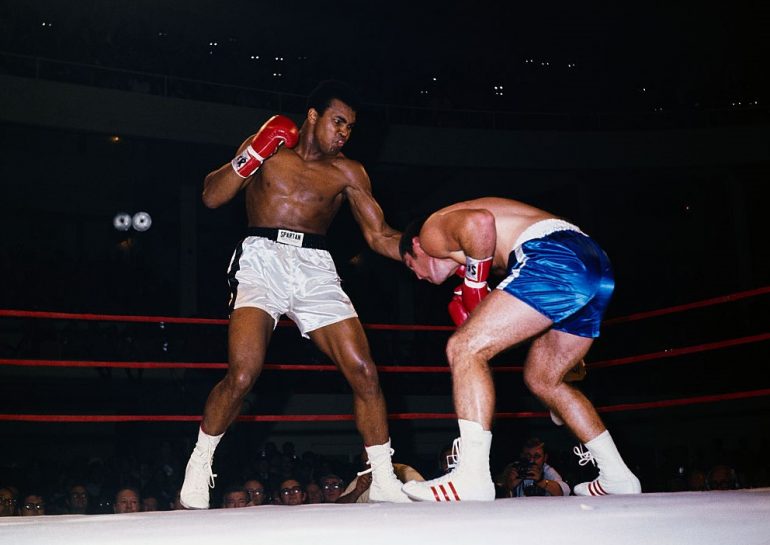

On October 26, 1970, 55 days after Ali fought an eight-round exhibition against three opponents at Atlanta’s Morehouse College, he was scheduled to meet Quarry, THE RING’s number-one contender and the WBA’s third-rated heavyweight, in a scheduled 15-round fight at the City Auditorium.

The following is an excerpt from “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” by Bob Canobbio and Lee Groves, which can be purchased, among other places, on Amazon as well as Barnes and Noble. While Bob and I are understandably biased, we believe that “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” would make a wonderful gift for the upcoming holiday season.

So, without further delay, enjoy this trip back in history.

*

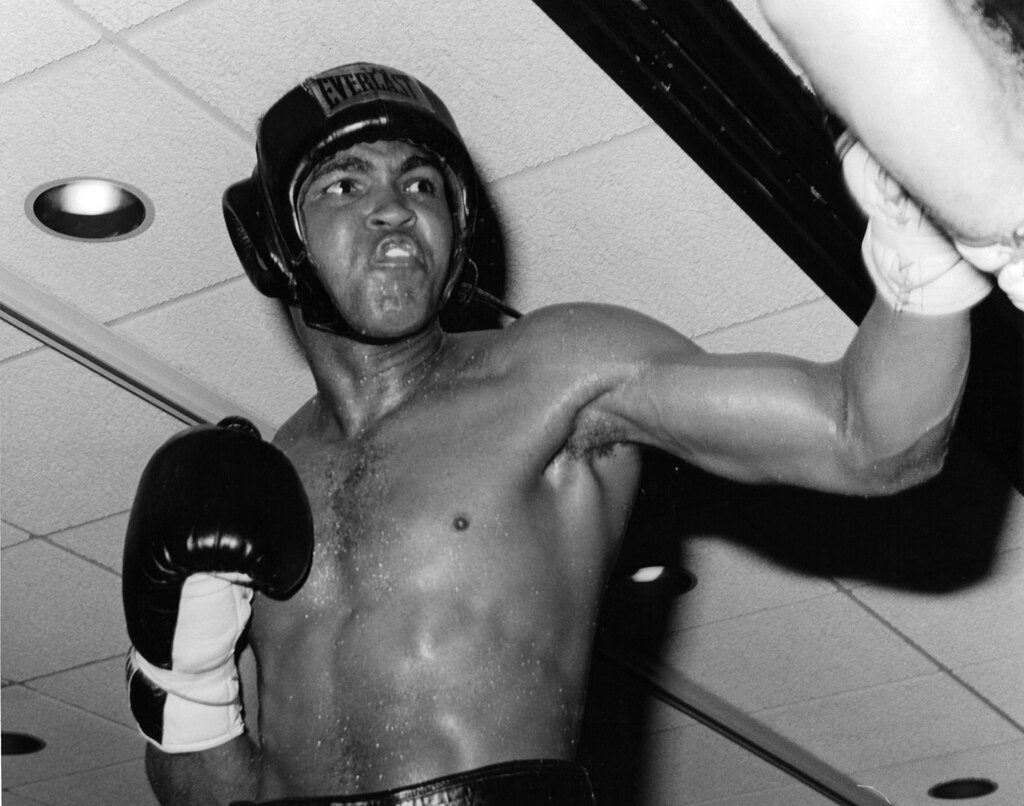

In boxing terms, a 43-month break between fights is the equivalent of an Ice Age. The combination of age and inactivity has historically robbed fighters of their sharpness, their fluidity, their timing and their ability to perceive, process and act upon split-second openings. That was the challenge facing Muhammad Ali when he signed to fight Jerry Quarry in a 15-rounder, a nod to his status as the lineal champion. Yes, Joe Frazier held the belts thanks to his knockout victory over Jimmy Ellis, the winner of the WBA heavyweight title elimination tournament, but the undefeated Ali remained “the man who beat the man.”

Up until this point in time, heavyweight history was replete with examples of champions failing to regain what they had lost following lengthy layoffs. John L. Sullivan lost his world heavyweight championship to James J. Corbett after not having fought for more than three years. Corbett, in turn, twice lost to James J. Jeffries following layoffs of 17 months and nearly three years while Jeffries emerged from almost six years of inactivity to lose to champion Jack Johnson. Joe Louis, who reigned as champion for nearly 12 years, was forced to return against his successor Ezaard Charles following a 27-month break. Although “The Brown Bomber” had his moments, he didn’t have enough of them and ended up losing a lopsided 15-round decision.

The only man ever to regain the heavyweight title at this point was Floyd Patterson, who vaporized previous conqueror Ingemar Johansson with a ferocious left hook 370 days after their initial meeting. The overwhelming difference between Patterson and the others, beside the shorter break between fights, was his age: 25. Sullivan was one month short of 34 when he lost to Corbett while Corbett was 33 and 36 when he challenged Jeffries. Jeffries was 35 against Johnson while Louis was 36.

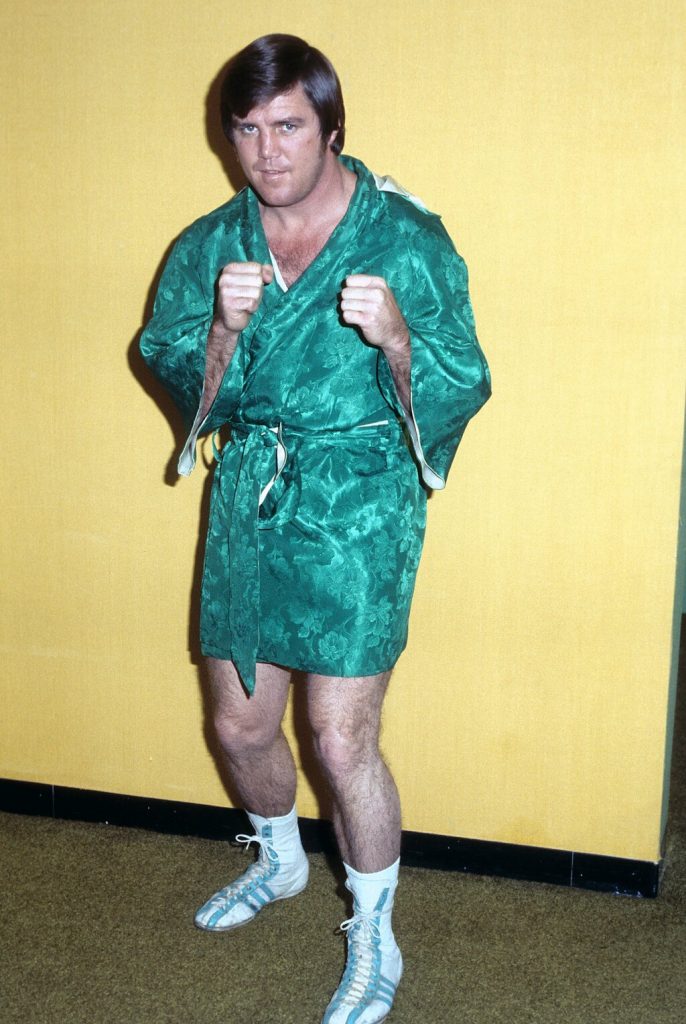

Entering the Quarry fight, Ali was three months shy of his 29th birthday, which meant that while he was still in his prime in terms of age he also was on the down slope of it. An additional challenge for Ali: In the 25-year-old Quarry, Ali was facing someone younger than himself for the first time in his professional career. In fact, Quarry was only the second Ali foe who had been born in the 1940s (Sonny Banks’ birthday was June 29, 1940).

Photo from The Ring archive

Moreover, “The Bellflower Belter” was a young veteran, for he came into the Ali fight with a 37-4-4 record that included 23 knockouts. His best punch was the left hook, the same punch Sonny Banks and Henry Cooper used to floor Ali. His victims included Brian London (W 10, KO 2), Alex Miteff (KO 3), Floyd Patterson (W 12 in their second fight), Thad Spencer (KO 12), Buster Mathis (W 12) and Mac Foster, the then-holder of the top spot in THE RING ratings who sported a 24-0 (24 KO) record before being stopped in six by Quarry, who took over the number-one slot with the win. (1) All of Quarry’s four conquerors were of high quality: Eddie Machen, George Chuvalo, Ellis and Frazier, the latter two coming in heavyweight title fights. The upside: The Frazier loss was deemed THE RING’s 1969 Fight of the Year. The downside: Two of Quarry’s four losses were by stoppage, and cuts played a role in both defeats.

Best yet for Quarry: He was unafraid.

“None of the noise surrounding the fight bothered me,” Quarry told author Thomas Hauser. “The more attention and publicity, the better. The crowd was 90 percent black and all for Ali, but that didn’t motivate me or intimidate me either. When I got in the ring, it was just another fight, even though the opponent was Ali. I wasn’t fighting against a symbol, I was fighting a fighter who had two arms and two legs just like me.” (2)

Factually speaking, Quarry was correct. But in reality, Ali versus Quarry was much more than a boxing match; it was a social happening of the highest order. The names around ringside belonged on everyone’s A-list: Actor Sidney Poitier, singers Diana Ross and Mary Wilson, Atlanta Braves slugger Hank Aaron, political figures Coretta Scott King, Julian Bond, Andrew Young and Jesse Jackson. Comedian Bill Cosby was blow-by-blow man Tom Harmon’s color commentator for the closed-circuit broadcast that was beamed to 206 locations in the U.S. and Canada and was shown live to Asia, Australia, Europe and South America. The City Auditorium was filled to its 5,100 capacity (3) but no facility in the world could have held the number of people that wanted to be there.

While one side celebrated Ali’s return to the ring, the other side seethed. Those who supported the Vietnam War believed Ali should not have been allowed to box again because, on June 20, 1967, he was convicted by a jury and then sentenced to pay a $10,000 fine and serve five years in a federal penitentiary. (4) Ali was allowed to await further legal developments outside of jail because he paid the bond, but despite the absence of prison walls, a legal and social cloud continued to hang over him. Because his case had not yet been fully resolved, the very thought of Ali inside a boxing ring, where he could generate millions of dollars for himself, made their blood boil.

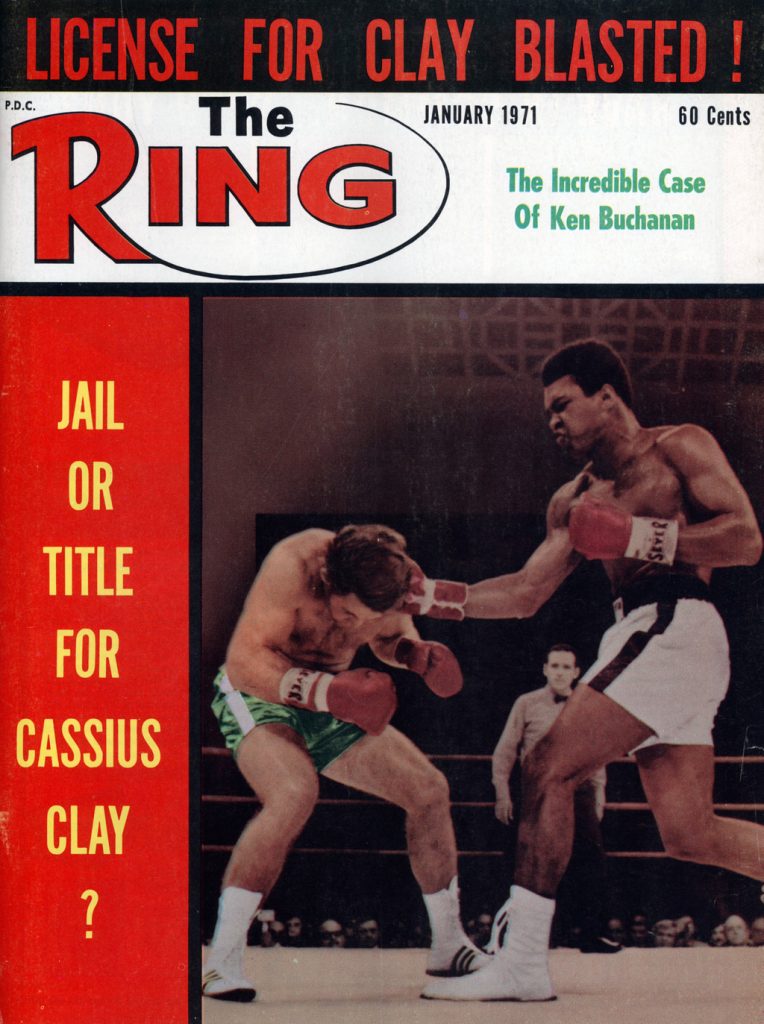

“Onlookers treated the TV showing (of Ali-Quarry) as if they were watching an actual fight,” THE RING’s Nat Loubet opined in his fight report. “Clay was the king. Clay was the real world champion, and to hell with the Justice Department. Intertwined with the adulation of Clay was his having been made the leader of the anti-war fans. To millions he represents strident opposition to the fighting in Vietnam. That Clay is under Justice Department charge as a felon for refusal to accept draft into the Army is not a minus with millions. It is a howling ‘hip hip hurrah’ for the man who would not yield to the draft and all for which it stands, the United States of America included.” (5)

To further illustrate the chasm between the two forces — and to express its opinion of who best represented the ideals of America — THE RING, in its January 1971 issue, ran a full-page black-and-white illustration by writer Ted Carroll of a “stars-and-stripes” shield accompanied by small drawings of Joe Louis and Jack Dempsey in fighting stances bookending a large bust drawing of a smiling Joe Frazier in the middle.

Photo from The Ring archive

No matter how one felt about Ali’s return to the ring, there was a palpable sense of curiosity and anticipation. The questions were plentiful: Would Ali be in shape? Would his legs have the same spring? Would his punches be delivered with sufficient timing and land with similar accuracy? Could Quarry connect with his formidable hook, and, if he does, would Ali be able to absorb it?

Ali weighed 238 pounds when he began training six weeks earlier (6) but when he stepped on the scale he was 216 1/2, five pounds heavier than he was against Folley and 18 1/2 pounds more than the 198-pound Quarry. Curiously, ring announcer Johnny Addie announced Quarry’s weight as 197 1/2 and Ali’s at 213 1/2.

“Who is the champion of the world?” a supercharged Ali yelled just before he weighed in.

“Jerry Quarry!” a sarcastic wag shouted from the back of the room.

“I got something for Quarry, and I got something for all of you!” Ali responded. “After tonight there will be no more Quarry. I’m sick and tired of it. All of this talk, taking my title, talking about new champs, all this phony stuff…This is the real game! This ain’t no phony game! That’s why I fight them all, regardless of risk. I’m a real fighter! All these chumps commercializing, you ain’t nothin’! I’m the real one! And all will bow to me in a few days. You all will bow to me!” (7)

Ali was clearly in prime verbal form at the weigh-in, but would he be in prime form at the fight?

One marked change was how Ali was received. He was booed vociferously through much of his three-year reign but here the cheers were overwhelming. Yes, it was a partisan crowd but it also reflected the overall attitudinal shift in the country.

When the action started, it was evident that while Ali was markedly thicker and slightly slower than the whippet-like creature that bedeviled the likes of Liston and Cleveland Williams, his form was still more than good enough to handle the likes of Quarry. With each passing second, however, the rust that encased Ali’s body began flaking off and by the start of the second minute he was raking Quarry’s face with stabbing jabs and lightning one-twos. Every Ali connect brought forth a wave of adoring screams.

Ali’s stilettos soon reddened Quarry’s nose and by round’s end Drew “Bundini” Brown, Ali’s longtime court jester, was shouting “All night long!”

The end of the round ignited another wave of cheers that were part celebration and part relief. Indeed, Ali, even now, was not only good enough to hold his own against a leading title contender, he was good enough to dominate him. In round one Ali out-threw Quarry 61-18, out-jabbed him 16-2 and prevailed 41%-17% overall and 36%-9% power. For those who dearly wanted him to succeed, all was right in the world again.

During the break, Quarry’s corner not only attended to the abrasion on his nose but also those underneath each eye, further evidence of Ali’s effectiveness.

The first moments of round two were proof positive that Ali was in fine working order as two searing jabs popped back Quarry’s head and his patented lean-back move allowed him to avoid a Quarry hook. The Californian determinedly pursued Ali behind his winging hooks, knowing that one flush connect would change not just the result of the fight but the arc of his life. But Ali was ready for everything Quarry tried and as a result most of his efforts produced a temporary breeze. By the final minute both fighters were bathed in perspiration, and though Ali controlled most of the round it was Quarry who landed the final punch, a long and heavy hook to the pit of the stomach.

January 1971 issue

While round two wasn’t nearly as dazzling, it was almost as effective. Ali threw more (49-27 overall), landed more overall (20-8) and in jabs (15-2) but, thanks to a nice surge in the last 30 seconds, Quarry prevailed 6-5 in power connects.

The first part of round three saw both fighters settling in and preparing for a potentially long fight. That said, Quarry was doing a better job of closing the distance, slipping the jab, maneuvering Ali toward the ropes and landing an occasional power shot. Ali’s output also was slowing a bit, which could have inspired post-mortem questions about his stamina. Yes, Ali’s nervous energy had vaulted him to an early lead but could he be effective over the long haul?

That question, at least on this day, would go unanswered because one of Ali’s knifing blows opened a gash over Quarry’s left eye, a patch of red Ali attacked with relish. A chopping right to the face widened the wound (which needed 11 stitches to close) and another along the ropes deepened his duress. Quarry was never seriously hurt, but the fact he made it to the round-ending bell was certainly worthy of note.

The between-rounds period hadn’t even reached its halfway point when an enraged Quarry bolted off his stool. After briefly working on the cut, Quarry’s chief second Teddy Bentham told referee Tony Perez that the fight had gone far enough. Perez briefly looked at the cut, then waved off the fight. A furious Quarry pushed Bentham away and stomped around the ring, but by the time he neared Ali’s corner he had calmed down to the point where he and Ali warmly embraced.

The statistics painted a bright picture for Ali. He led 57-17 in total connects, 38-4 in jabs and 19-13 in power connects while also being the more precise hitter (38%-25% overall, 38%-18% jabs and 40%-28% power). All in all, Ali couldn’t have asked for a better first night back.

It didn’t take long for Ali to address the one subject boxing fans wanted to hear about most — a future showdown with Joe Frazier.

“I’m ready to settle the title,” Ali said.

“We’re ready to fight him as soon as we get rid of (Bob) Foster (Nov. 18) and as soon as Clay can get ready,” Frazier’s manager Yank Durham said at Frazier’s training camp in East Stroudsburg, Pa. (8)

But before Ali and Frazier could get their hands on each other, the self-proclaimed “Greatest” had one more assignment to complete — a December 7 date with Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden.

INSIDE THE NUMBERS: The returning Ali resorted to his bread and butter against Quarry — the jab. It comprised 68% of his thrown punches as well as 67% of his landed punches. Quarry managed to land just 4 jabs to 38 for Ali.

Footnotes: (1) “Here Comes Foreman: Contest Against Quarry Would Be a Natural,” by Dan Daniel, THE RING, November 1970, p. 36

(2) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 211

(3) “Ali Finishes Quarry in 3; Stage Set for Frazier Fight,” by Ed Schuyler Jr., Associated Press, published in the Owosso (Mich.) Argus-Press, October 27, 1970, p. 14

(4) “Clay Guilty in Draft Case; Gets Five Years in Prison,” by Martin Waldron, The New York Times, June 20, 1967, p. 1A

(5) “Now It’s Frazier vs. Clay: Atlanta’s Nine Minutes Set Up Precedent Which Boxing is Not Eager to See Repeated,” by Nat Loubet, THE RING, January 1971, p. 10

(6) “Ali Finishes Quarry in 3; Stage Set for Frazier Fight,” by Ed Schuyler Jr., Associated Press, published in the Owosso (Mich.) Argus-Press, October 27, 1970, p. 14

(7) “Ali Finishes Quarry in 3; Stage Set for Frazier Fight,” by Ed Schuyler Jr., Associated Press, published in the Owosso (Mich.) Argus-Press, October 27, 1970, p. 14

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE