Epic Holyfield-Qawi war was part of Real Deal’s ‘Omega Project’ path to Mike Tyson

Anyone familiar with Aesop’s Fables knows the tale of The Hare & The Tortoise, which holds that “the race is not always to the swift.”

And so it was, providentially, for Evander Holyfield and some of his handlers at a critical juncture in Holyfield’s still-young professional boxing career, when a long-range plan was hatched that would eventually transform the 1984 Olympic bronze medalist from a very promising cruiserweight into a heavyweight formidable enough to take down the seemingly invincible monster of the big-boy division, Mike Tyson.

All right, so the “Omega Project” didn’t work out exactly as first envisioned by Holyfield’s then-promoter, Main Events president Dan Duva, and other inner-circle speculators who bought into Duva’s long view of what the scientifically-modified Atlanta resident could become if he fully bought into the program and had the requisite patience to stay the course. A 42-to-1 longshot, James “Buster” Douglas, demonstrated that an increasingly disinterested Tyson was indeed human when he knocked out the fight game’s most frightening Godzilla in Tokyo on Feb. 11, 1990, predating by six years and nine months the fulfillment of Holyfield’s delayed destiny, an 11th-round stoppage of the favored Tyson, on Nov. 9, 1996, in Las Vegas. Holyfield would follow that watershed victory with another in the rematch on June 28, 1997, when Tyson – possibly looking for a way out of another loss by conventional means, as some have hypothesized, gnawed off a part of Evander’s right ear and was disqualified in the third round of what came to be known as the “Bite Fight.”

But, in retrospect, the Omega Project – which vaguely sounded as if it had something to do with secret agents or the development of a weapon of mass destruction in some remote underground facility – worked exactly as Dan Duva had imagined. It was unfortunate that Duva, who was only 44 when he died of a brain tumor on Jan. 30, 1996, didn’t live quite long enough to see his grand plan through to fruition.

Evander Holyfield is flanked by co-trainers Lou Duva and George Benton (right), prior to his 1987 rematch with Dwight Muhammad Qawi in Atlantic City. The two boxing sages, along with Main Events and several conditioning consultants, envisioned Holyfield as the man to eventually beat then-undefeated heavyweight champ Mike Tyson. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

“We call this the Omega Project because we feel Evander Holyfield is the last man who can beat Mike Tyson,” Dan Duva said in the spring of 1986, when the decision was made that the then-23-year-old Holyfield, if he were maximize his potential for ring greatness, had to improve his most obvious perceived weakness, which was a lack of stamina that might prove troublesome in the later rounds against quality opponents. In winning his first 11 pro bouts, Holyfield had not been obliged to go more than eight rounds, and even so there were indications he might not be able to sustain himself at a peak level of a fight that might have to go even 10 rounds, much less the then-championship distance of 15.

Prior to Holyfield’s challenge of a physical and stylistic prototype of Tyson, WBA junior heavyweight (as the 190-pound division was then called by that sanctioning body) champion Dwight Muhammad Qawi, Duva enlisted the aid of R. David Calvo, an orthopedic surgeon who ran a sports medicine clinic in Sugar Land, Texas, and Houston-based conditioning specialist Tim Hallmark. Their mission: increase the capacity of Holyfield’s gas tank, which seemed to be an absolute necessity if he was to test himself against Qawi, the “Camden Buzzsaw,” whose stock in trade was relentless, Tysonesque pressure. A loss might have irreparably set Holyfield back in many fight fans’ minds as a down-the-road threat to “Iron Mike,” or at the very least demonstrated the folly of pairing the hot kid with a battle-tested, experienced veteran (Qawi was 33) before he was ready to take such a big step up.

Although Holyfield was denied a deserved gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the ’84 Los Angeles Olympiad by a Bulgarian referee who wrongly disqualified him in the semifinals for throwing a knockout left hook to the jaw of New Zealand’s Kevin Barry a split-second after the bungling ref had yelled “Stop!,” he initially was not widely regarded as the most prized acquisition of Main Events’ five-Olympian signing class. There were so-called experts who believed that Mark Breland, Meldrick Taylor and Pernell Whitaker all had better chances for immediate and/or lasting pro success. But none of the other Main Events Olympians had been as fast-tracked to a title shot as was Holyfield, raising questions as to why he was being given the group’s first opportunity to become a world champion.

“How can you possibly rush a kid who has as much talent as Evander? He’s ready now,” said Holyfield’s manager and co-trainer, Lou Duva, Dan’s father. “The only obstacle for Evander was to get into good enough shape physically to be prepared mentally to go more rounds.”

Qawi, for one, figured that Holyfield, who at 6-foot-2 was seven inches taller and had a seven-inch reach advantage, was in for a rude awakening, despite the hometown hero being an 8-to-5 favorite in the bout before a supportive crowd in Atlanta’s Omni. “My struggle was far greater than his,” Qawi, who did time on an armed-robbery conviction and turned pro without the benefit of having had even a single amateur fight, said of Holyfield, whose Olympic pedigree ostensibly stamped him as a beneficiary of his sport’s star-making machinery.

“I came through it and I earned it. I don’t want anybody to give me anything. Just open the door the night of the fight, let me step in the ring and I’ll take it myself. I’ve been the underdog before.”

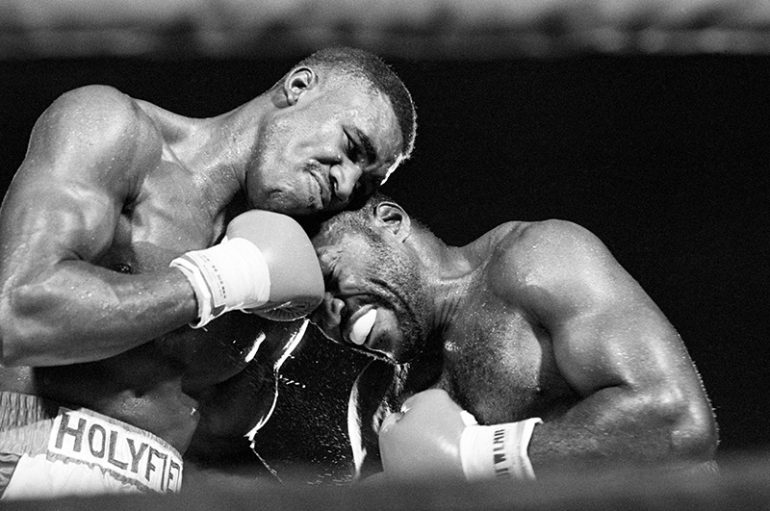

Holyfield and Qawi go at it during their epic first fight. (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images.)

As litmus tests go, Holyfield-Qawi I – there would be a do-over on Dec. 5, 1987, when Holyfield defended his WBA and IBF cruiserweight straps on a much more convincing fourth-round knockout in Atlantic City – was all that had been promised, and then some. In scoring a rousing, split-decision victory that many still consider to be the best cruiserweight matchup of all time, Holyfield, despite some ongoing concerns about his stamina, averaged around 85 punches per round, an astounding work rate for someone his size, although that number could not be quantified until much later, after an examination of the tape by punch-counters for CompuBox, a company which did not exist in 1986.

“I didn’t ever think about what would have happened if I lost (to Qawi) because I never thought about losing,” Holyfield told me in 2017. “You can’t be afraid to take a chance to be the best, and I wanted to be the best. I just didn’t know what the best was.”

George Benton, Holyfield’s primary trainer and strategist, always pointed to the first Qawi fight as the moment when the soon-to-be undisputed cruiserweight champion and future four-time heavyweight ruler broke through to the next level, at which he resided for another couple of decades. “July 12, 1986,” stated Benton, a 2011 inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame who was 78 when he died on Sept. 19, 2011. “That’s when it all came together for Evander. That’s the day we knew we had something special.”

To his credit, Holyfield was not yet as new and improved as the crafters of the Omega Project had hoped to achieve in the short window from inception to implementation. Examined by a ring physician in his dressing room, Holyfield was informed that his body was burning muscle, which could have caused his kidneys to fail. He was rushed to a hospital where he was administered nine liters of intravenous fluids. When he awakened, it was at a weight of 201 pounds, or 15 more than what he had registered at the weigh-in the day before.

But the Omega Project proved to be a work in progress, and a hugely rewarding one at that. Holyfield, at Lou Duva’s insistence, a strange development given Cap’n Lou’s rotund frame, swore off the high-caloric junk food he loved and dedicated himself to the fitness regimen mandated by Hallmark, even after the Omega Project ceased to be a topic of conversation. Perhaps because of the improvements he recognized within himself as a result of that first Qawi fight, Holyfield became an inveterate tinkerer, his own laboratory test rat. Over time, his retinue expanded to include ballet instructor Marya Kennett, bodybuilder Lee Haney, strength coach Chasee Jordan and computer analysts Logan Hobson and Bob Canobbio, the founders of CompuBox. Some of those additions confounded Lou Duva, who was instrumental in the creation of the Omega Project, and Benton, who wondered if too much experimentation was having more of a negative effect than a positive one.

“I’ve been doing this a long time,” Holyfield, who praised Kennett for greatly improving his flexibility, said of the constant fine-tuning. “I know better than anyone else what I need to get myself ready.”

All of which raises a question: if Holyfield was tossed into the deep end of the pool against a rugged Tyson clone like Qawi at such an early stage of his professional development, how is it that he now stands as the race-winning tortoise in the boxing equivalent of that particular Aesop Fable? Well, it depends on which way you choose to look at it. In comparison to Tyson, who became the youngest heavyweight champion of all time when, at 20 years, three months and eight days of age, he dethroned WBC titlist Trevor Berbick on a second-round stoppage, Holyfield’s progress up the pro ladder was almost tedious. Not only that, but Holyfield by nature is a patient sort, not inclined to force something before the time is right. He’s been like that from the very beginning, when he took up boxing at the tender age of eight at the Warren Boys Club in Atlanta.

“The coach told me I could be like Muhammad Ali,” Holyfield said at his induction into the IBHOF in 2017. “I told the coach I was eight years old. He told me I wouldn’t always be eight. And I believed him, ’cause the next week I was gonna be nine.

“My first fight, I fought a guy and my coach said, `You see that kid there?’ I said, `Yes, sir.’ He said, `(When) the bell rings, I want you to hit him right in the nose.’

“I looked at the kid and his coach was telling him to hit me in the nose. I got down in my stance, the bell ring, the kid ran out there and I ran out there. But he closed his eyes. I didn’t close my eyes. I hit him right in the nose. He started crying. The referee stopped the fight and my coach, Carter Morgan, who was about 70 years old, was so excited. He raised my hand and told me I took the first step to being the heavyweight champ of the world.”

Mike Tyson and Holyfield on stage at the press conference for their originally scheduled showdown in 1991. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

It was 14 years from that that first fight to the first scrap with Qawi, and another 10 years and four months before Holyfield, who already had been an undisputed heavyweight champ, got his initial shot at Tyson. All of which begs another question: What would have happened had there not been three postponements that kept Tyson-Holyfield on the back burner for so long? They were set to have squared off on Nov. 8, 1991, but Tyson, a 2-to-1 early-line favorite, suffered an injury to his left rib cage on Oct. 7, pushing the fight date back to Oct. 18. Tentatively rescheduled for an unspecified date in January 1992, that also went by the boards when Tyson’s ribs hadn’t healed quickly enough prior to his rape trial, which began on Jan. 27. The fight everyone wanted to see then was canceled when Tyson was convicted and was incarcerated for three years.

It is emblematic of the direction in which the two fighters seemed to be heading when Tyson, who had won four straight bouts on the comeback trail after being released from prison, was an opening-line 25-1 betting choice over Holyfield, who had gone only 4-3 in his seven preceding outings, including a desultory fifth-round stoppage of Bobby Czyz that gave the impression that the “Real Deal” was close to running on empty.

Although the huge gap in the odds was whittled down to 10-1 by fight night, 47 of 48 boxing writers who were polled picked Tyson to soundly beat a 34-year-Holyfield presumably on the downhill side of an exemplary career. The only dissident was the Boston Globe’s Ron Borges, who remembered an incident at the 1984 U.S. Olympic site in Colorado Springs, Colo.

“Oh, sure, there are a lot of people who say now that they always knew Holyfield would beat Tyson,” Borges said in 2017. “Back then (1996), nobody thought Holyfield had a chance. There was a lot of talk after his fight with Czyz that Holyfield was damaged goods and shouldn’t even be allowed to fight Tyson.

“One of the things I knew, dating back to when Holyfield and Tyson were amateurs, was the pool table incident. One night they were all playing pool at the Olympic Training Center in 1984 and it was one of those deals where if you lost, you gave up the table. Tyson lost and it was Holyfield’s turn to play. Tyson tried to bully him. Holyfield walked up to Tyson, didn’t say a word and took the cue stick from him. Tyson left the room and nobody saw him for the rest of the night. I always had it in the back of my mind that Tyson knew if there was one guy he couldn’t intimidate, it was Evander Holyfield.”

Tyson was an interested ringside observer at the Holyfield-Qawi rematch. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images.)

Hindsight always being 20/20, the consensus now is that Holyfield would have handled Tyson at any point of their respective boxing journeys. For a story I did some years ago, Tommy Brooks, who for a time worked with Tyson, said, “If that fight had gone off as planned in 1991, it would have been the same outcome as the one five years later. Evander just had Tyson’s number. Sometimes that’s just the way it is.”

Added Nigel Collins, former editor of The Ring: “The secret of winning at that level is having a strong mind. Evander Holyfield could have fought Mike Tyson at any time in their careers and would have won 99 times out of 100 because he had such a strong belief in himself. Really, there were only four or five years when Tyson was a truly great heavyweight. Holyfield had a much longer career at the top. I’m very fond of Tyson and always enjoyed covering him, but Holyfield will go down in history as the superior fighter.”

That discussion is apt to go on for as long as fight fans care enough to voice their own particular opinions. But one thing now seems certain: the Omega Project was indeed a gamble worth taking.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE