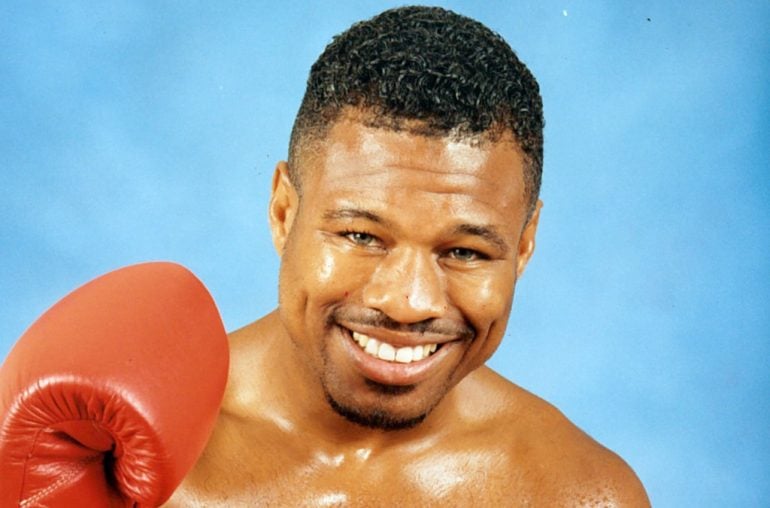

From The Archive: Sugar Shane Mosley – Wait ‘til you get a taste of this lightweight

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the August 1997 issue of The Ring Magazine.

It’s Saturday afternoon in Pomona, California, and the man who just might be the best 135-pounder in the world is watching the finish of the WBC lightweight title fight between champion Jean Baptiste Mendy and Steve Johnston. The 12-rounder, televised from Paris by ABC, has gone the distance, and either fighter could be declared the winner.

The resident of the small desert town 60 miles east of Los Angeles sits up and fixes his light green eyes on the television screen as the decision is translated from French. Mosley is eerily silent as Johnston is announced the winner by split decision.

No one in the living room, which includes Mosley’s father and trainer, Jack, and his mother, Clemmie, says a word. But the fighter’s parents are painfully aware this is the third time their son has watched a former amateur rival win a lightweight title.

As an amateur, Mosley defeated Oscar De la Hoya (when the boys were 12 or 13) and Rafael Ruelas, both former IBF lightweight champions. And he won two of three vs. the newly crowned Johnston. As a pro, Mosley has racked up 22 wins (21 by kayo), but despite his undefeated record and crowd-pleasing style, he’s toiled in relative obscurity, especially in comparison to the careers of other standouts of the Class of ’92.

“When I look at photos of the ’92 team and see guys like De La Hoya, Larry Donald, Raul Marquez, Jeremy Williams, Paul Vaden, Ivan Robinson, and Sergio Reyes, guys who have made a name for themselves, I feel left out,” Mosley said. “It’s like they’re at this great party and I wasn’t invited. I want to join that party, and I want to make a grand entrance.”

Before Mosley signed with Cedric Kushner Promotions, it seemed the contender would never get near the door, much less through it. Ten months of inactivity caused by contract disputes with his former promoter, Patrick Ortiz, nearly dropped him from the top 10 of the major alphabet organizations. Since hooking up with Kushner, Mosley has fought twice and is ranked fifth by the IBF and 12th by the WBC. But can the fighter West Coast trainer Joe Goossen calls “the best lightweight in the world that nobody knows” catch up with his former amateur rivals?

Those who have seen him fight believe Mosley possesses not only what it takes to defeat any of the current lightweight champions, but that special quality to become one of boxing’s superstars.

“Mosley is the class of the lightweight divisions,” says Goossen, who guided Ruelas and his brother Gabe to world titles. “His talent is almost Roy Jonesesque. In terms of pure skill, I’d say he’s even better than Jones because he executes a more controlled, fundamentally sound fight in the ring.”

Mosley (left) lands a punch against Joseph Murray in a 1996 bout. Photo from The Ring archive

Longtime ESPN analyst Al Bernstein says the 5-foot-8 Mosley has more raw talent than any fighter he’s seen in recent years. “I think he’s the only guy out there with the physical tools, the skills, and the panache to beat De La Hoya,” he said. “He has speed, he has power, he has that something. He’s dazzling in the ring.”

It is Mosley’s hand speed that has dazzled both onlookers and opponents since he first tagged along with his father to a local gym when he was eight years old. Although Jack, who boxed as an amateur, was going to the gym only to lose weight, he occasionally showed his eager and energetic son a few boxing moves. Mosley quickly mastered every punch, counter-punch, dip, feint, step, and block his father taught him, executing everything with speed, balance, and grace. Older trainers in the gym gave him the nickname “Sugar” because his style reminded them of a miniature Sugar Ray Robinson.

Mosley went on to compete in more than 250 amateur bouts. From 1989 to ’92, he was ranked first nationally at 132, and then 139 pounds. At the 1992 Olympic Trials, he lost in the semifinal to Vernon Forrest, who went on to fight at the games in Barcelona. “That was the ultimate low for me in the amateurs,” he told The Ring in late-1993. “I guess the computer [scoring system] just didn’t fit my style – the judges couldn’t score many of my punches because I was so quick.”

Fighting in California, Mosley turned pro in 1993 and scored kayos in his first nine fights. In his 13th pro bout, he stopped former NABF 130-pound champion Narcisco Valenzuela, who had knocked down De La Hoya. Four fights later, Raul Hernandez, who had just gone the distance with Gabe Ruelas, was blown out in two.

As tough and grizzled as these fighters were, they lacked name recognitions outside of Southern California’s Mexican community. Fights with better-known lightweights, such as Leavander Johnson, George Scott, John-John Molina, and Johnston, eluded Mosley, and so have the fame and exposure that come with such matchups.

“The shame of the boxing world is that no one has had a chance to see Mosley,” said Bernstein. “He’s in his prime and should have won, or at least fought for, a world title by now”

But, explained Goossen, “In today’s market, one loss can set your fighter back two years. If I had an up-and-coming lightweight who I wanted to take to the top, I would swim away from Shane Mosley.”

The Mosley camp almost snared WBA champion Orzubek Nazarov, but the Japan-based Russian outpriced himself during last-minute negotiations. It was then that Mosley decided to sign with Kushner.

“I was fighting for $2,000 and $4,000 purses when I was 15-0,” Mosley said. “[Steve] Johnston was on ESPN when he was 15-0, and ranked number one by the WBC. He was probably fighting for at least $30,000 a fight.

“I know boxing is a poor man’s sport until you get exposure, but looking at how low I was in the ratings, I began to wonder if I was ever going to get a chance to show my talent.”

“The ratings are so confusing to me. Who did Lamar Murphy beat to get those two shots at the WBC title [vs. Miguel Angel Gonzalez and Mendy]? Why were Molina and Scott always rated ahead of me? Molina was a champion, but at 130 pounds. Scott was knocked out by Jake Rodriguez.”

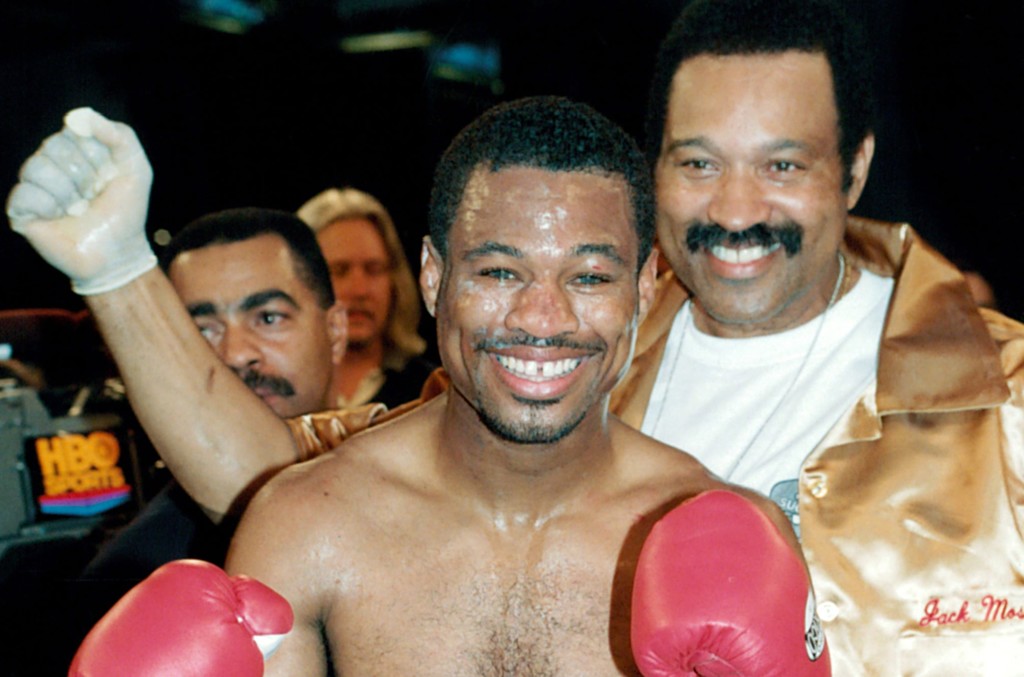

Mosley with father-trainer, Jack. Photo from The Ring archive

Unable to secure a breakthrough bout, Mosley widened his reputation in LA gym wars against the likes of Julio Cesar Chavez, Azumah Nelson (when Mosley was 15), Genaro Hernandez, Hector Lopez, David Kamau, and Zack Padilla.

The now-retired Padilla, a non-stop punching machine, estimates he worked 1,000 rounds with Sugar Shane.

“Shane’s speed is his power,” said Hernandez. “All his punches, no matter what angle they come from, have that snap to them. His jab is even faster than De La Hoya’s.”

So with everyone speaking of Mosley as a combination of Benny Leonard, Roberto Duran and Pernell Whitaker, when are going to see him against the elite? Forget a bout against a name contender; more likely than not, he’ll jump directly into a world title fight.

“This is the most excited I’ve been about a single fighter in a long time,” said Kushner. “I’m looking for a June or July HBO Boxing After Dark challenge against (IBF champion) Phillip Holiday.” As we went to press, it seemed likely Holiday-Mosley would materialize on July 26.)

“It makes sense to move Mosley right into a title fight,” said Bernstein. “He’s ready to take off, and he could explode like a De La Hoya or a Sugar Ray Leonard.”

All he needs is a chance , which, for a fighter who’s been special since his early teen years, is a long time coming.

Watching Steve Johnston’s post-fight interview after the southpaw’s title-winning victory over Mendy, Mosley asks his father’s opinion of the fight.

“Steve did a good job,” says Jack Mosley, “but he should’ve been more of the attack.”

Shane nods in agreement. “They were boxing for a world title. I’m going to be fighting for it.”

A young fighter can be expected to wait only so long. Before Johnston’s interview is over, Mosley leaps from the couch and screams at the TV set: “Let’s get it on!”

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE