A Fan Remembers: Bobby Chacon vs. Cornelius Boza-Edwards II

On December 11, 1982, Bobby Chacon became a world champion for the second time with one of boxing history’s best storybook finishes. Following his drama-dripped unanimous decision victory over Rafael “Bazooka” Limon to capture the WBC junior lightweight championship, many wondered what Chacon could possibly do for an encore. Thirty-seven years ago today, “The Schoolboy” gave us his answer – and what an answer it was. His rematch with Cornelius Boza-Edwards on May 15, 1983 at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas featured jurisdictional and promotional rancor, fabulous in-ring action, a controversial call from ringside commentator Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, a ringside physician who played a prominent role, an angry letter by a future boxing writer and a surprising result.

Today’s tale will weave all of these elements into a sustained narrative but here’s some fair warning: This story will take a while to tell. So sit back, relax and allow yourself to be transported back to a time when there were only two world sanctioning bodies but also a world’s worth of complications.

*

For those of us who love boxing history, tracing the line of succession for the various divisional championships – and reliving those fights that link the previous king to his successor – is one of our favorite pastimes. That passion extends to lineages that are highly unofficial in nature, of which one is boxing’s “Warrior King.” The owner of that crown never fails to deliver adrenaline-pumping action and counts pleasing his audiences as one of his main responsibilities.

Fighters such as these operate within a circle of benevolence, the opposite of the vicious circle: The virtual guarantee of two-way violence attracts the very fans whose sonic support fuels the fighter’s passionate performances and those performances, in turn, keep those fans coming back while also attracting new ones. Ideally this symbiotic relationship lasts for years and those truly special monarchs are able to sustain it even after defeats. For them, the honesty of their efforts – win or lose – are enough to keep the train on its tracks.

On April 22, 1979, Matthew Franklin not only won the WBC light heavyweight title from fellow action hero Marvin Johnson, he established himself as boxing’s newest Warrior King. As Matthew Saad Muhammad, his championship reign lasted longer than most fighters of his kind – eight successful defenses spanning more than two-and-a-half years – and in that time, he earned a “Fight of the Year” award from THE RING for his thrilling 14th round TKO over Alvaro “Yaqui” Lopez. But the wear and tear of his reign – combined with the rigors of making weight and the demands of fighting off the raging Dwight Braxton – resulted in the end of his dynasty, which was brought down in most brutal fashion when the man who soon would be known as Dwight Muhammad Qawi stopped him in 10 rounds on December 19, 1981.

It didn’t take long for the next Warrior King to be identified and while that man stood five-and-a-half inches shorter and scaled 45 pounds lighter than Saad Muhammad, the fighting spirit that animated him was much the same. On December 11, 1982, before a boisterous and highly partisan crowd at Sacramento’s Memorial Auditorium, Bobby Chacon completed a seven-year odyssey to regain what he had so foolishly lost to Ruben Olivares as a party-hearty 23-year-old in June 1975 – a world boxing championship. In a journey that included two failed title opportunities against Alexis

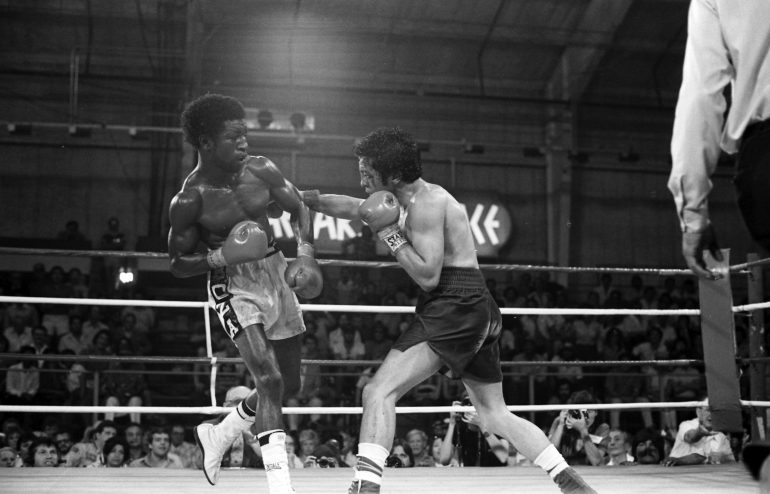

Bobby Chacon (L) goes toe to toe with ring rival Rafael “Bazooka” Limon, who he faced four times. Their fourth match, won by Chacon, was THE RING’s Fight of the Year for 1982.

Arguello and Cornelius Boza-Edwards and the suicide of his wife Valerie the day before his March 1982 fight with Salvador Ugalde, Chacon channeled his considerable physical and emotional pain to deliver one of the most melodramatic performances ever produced inside the squared circle against defending WBC junior lightweight titlist Rafael “Bazooka” Limon. Trailing on two scorecards and even on the third entering the 15th round – thanks, in part, to the knockdowns he suffered in Rounds 3 and 10 – Chacon flattened Limon with a pair of right hands in the fight’s waning seconds. The severely buzzed Limon somehow regained his feet, a feat which threw the fight into the hands of judges Carlos Padilla, Angel Luis Guzman and Tamotsu Tomihara.

Had the knockdown not ofccurred, Limon would have retained his championship with a majority draw. But because the knockdown did happen, Chacon dethroned Limon by one, one and two points and won their bitterly contested tetrology 2-1-1. This 18-year-old Sistersville High School senior, like millions of others, was euphoric over the result and the editors of THE RING deemed it its 1982 “Fight of the Year.” Because of the combination of scintillating back story, pulse-pounding action and cinematic ending, I count Chacon-Limon IV as the single greatest fight I’ve seen in my 46 years as a boxing fan. I have witnessed several worthy contenders since then but I doubt that any match will ever replace this Sacramento slugfest in my mind and in my heart.

With the championship belt safely around his waist, Chacon and his team contemplated their next move. Under normal circumstances, that move would have been set in stone; as ABC’s Keith Jackson reported during the broadcast of Chacon-Limon IV, the winner was obligated to fight the No. 1 contender, former WBC beltholder Cornelius Boza-Edwards. Boza-Edwards, who was shockingly dethroned by late-sub Rolando Navarrete in August 1981, was viewed as such an overwhelming favorite over both Limon and Chacon that Jackson called him “in effect, the champion” while detailing the scenario.

Boza-Edwards nails Chacon en route to winning their first fight at Showboat Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

There was ample reason for the legendary broadcaster to feel that way: Boza-Edwards defrocked Limon by unanimous decision in March 1981, then forced an exhausted Chacon to retire on his stool between Rounds 13 and 14 of their May 1981 clash. Thanks to victories over Juan Carlos Alvarez (KO 3), Arturo Leon (KO 4), Carlos Hernandez (KO 4), John “The Heat” Verderosa (KO 3), Roberto Elizondo (UD 10), Blaine Dickson (UD 10) and Pedro Laza (KO 9), Boza-Edwards became Chacon’s top challenger as seen by the WBC. The rematch with Boza-Edwards was attractive to Chacon for two reasons; first, it would give him the chance to avenge an earlier loss and second, it offered a much larger payday.

However these were not normal circumstances, and the reason can be boiled down to a single name: Don King.

In order for Chacon to secure the title match with Limon, the fighter signed a promotional deal with King that allowed the frizzy-haired Ohioan to pick his next opponent should he emerge victorious. And the opponent King wanted Chacon to fight was not Boza-Edwards but Hector “Macho” Camacho, an undefeated southpaw who owned lightning-quick hands as well as unquestioned star power. At 20, Camacho was more than a decade younger than Chacon and King saw him as a more reliable – and a far more lucrative – long-term proposition. With Sugar Ray Leonard forced to retire due to a detached retina, boxing needed a new “face” and, in King’s mind, Camacho was that face because of his megawatt smile, flashy wardrobe, street-smart persona and unmistakable talent. To King, Chacon was merely the tool by which he could begin the Era of Camacho.

One possible motivation behind King’s maneuvering could be found in a May 15, 1983 New York Times story written by Hall-of-Famer Michael Katz. Because he owned options on Chacon’s next three fights, King was able to ink a deal with Camacho’s promoter Jeff Levine in which King secured the rights to co-promote Camacho’s first six title defenses – and this accord was achieved despite the fact that Camacho was not a world champion – at least not yet.

King was best known for his tight-fisted control of the heavyweight division – at the time King owned the rights to both heavyweight champions (Larry Holmes and Michael Dokes) as well as six of the top 10 contenders – but his influence extended far beyond the big men. According to Katz, King was linked to 13 of the sport’s 27 recognized world champions. One major source of King’s clout was his association with WBC President Jose Sulaiman, whose power over the organization was absolute.

Sulaiman had final say on all WBC-sanctioned contests but his organization’s rules regarding title defenses was clear-cut: Upon winning the title, the defending champion was obligated to face his No. 1 challenger within a specific timeframe but within that timeframe, he had the right to face anyone ranked in the organization’s top 10. Chacon, however, wanted to go straight to his mandatory challenger Boza-Edwards and, under most

WBC President Jose Sulaiman, Julio Cesar Chavez and promoter Don King. Photo from The Ring archive

circumstances, he would have been lauded for his bravery. Sulaiman, however, ruled that King’s contractual rights to Chacon were sacrosanct and because King wanted Chacon to fight Camacho next, the WBC president would not sanction a fight between the WBC champion and the WBC’s No. 1 contender.

Think about that for a moment: The president of a sanctioning organization felt it more important to cater to the interests of a specific boxing promoter than to uphold the very rules he is charged to apply. If ever a situation captured the fluidity – and the absurdity – of boxing administration, this was it.

But another powerful force in boxing – television – stepped in to make sure the second fight between Chacon and Boza-Edwards would take place. NBC, which won the rights to televise the bout and wanted to use the event to pump up its ratings for May sweeps, gave Don Chargin, who was to promote Chacon-Boza II, $575,000, of which $450,000 went to Chacon. That amount far out-stripped the $210,000 purse King offered Chacon to fight Camacho and, although Chacon was assuming a huge risk, he had 450,000 reasons to be enthusiastic about defending against Boza-Edwards.

Boza-Edwards, for his part, refused a $150,000 step-aside offer from King in order to take the $110,000 purse to fight Chacon.

“I want to win my title back,” Boza-Edwards told the New York Times. “I don’t fight for money.”

King responded with a succession of lawsuits – one of which was an $8.5 million action against NBC – and, according to the July 1983 issue of THE RING and the New York Times, King secured an injunction barring the fight from a Los Angeles County court three days before it was to take place (the papers were filed in California because Chacon signed the original agreement with King in Sacramento just four days before his title-winning bout with Limon). But neither NBC nor Caesars Palace in Las Vegas – the fight’s site – yielded; in fact, Caesars wanted to bill the bout as being for “The People’s Championship” before the Nevada State Athletic Commission forced the casino to re-brand it as a match between “the people’s champions.”

Less than an hour after the injunction was activated, the California Court of Appeals issued a stay. With that, the fight was back on.

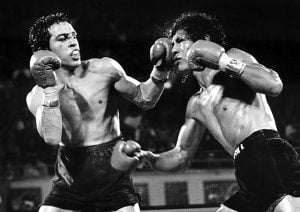

Chacon wasn’t able to last the 15-round distance with Boza-Edwards the first time they fought. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

The overriding question surrounding the bout was, “How much did Chacon have left following last December’s war with Limon, a man Boza-Edwards had defeated convincingly?” That was especially relevant given what happened in their first meeting in May 1981, which was also staged in Las Vegas inside the Showboat Hotel and Casino. Although Chacon repeatedly nailed Boza-Edwards with straight rights throughout the match – one almost scored a knockdown in Round 9 – the England-based Ugandan’s superior physical strength, straighter punches and accurate combinations bloodied Chacon’s nose and puffed his left eye by Round 3, then created a gash on the left eyelid in Round 11. At the end of 13 rounds, Boza-Edwards had built leads of 128-120, 127-120 and 124-123 on the scorecards and the champion’s withering attack prompted Chacon’s manager to ask referee Carlos Padilla to stop the fight. Given the flow of Fight One – and the fact that the 31-year-old Chacon was two years farther away from his prime while the 26-year-old Boza-Edwards was at his chronological crest – the challenger was installed as a 4-to-1 betting choice.

Chacon declared he would not repeat his Fight One mistake of seeking the early KO but once the bell sounded, he was sucked into a give-and-take war in which both men landed solidly and frequently. In the round’s final minute, Chacon voluntarily retreated to the neutral corner pad and pulled off the same ploy that had been so effective against Limon last December: Allow the opponent to bomb away, then spring out of the corner behind a series of solid right hands. In the round’s final seconds, Chacon connected with a short right to the jaw that caused Boza-Edwards’ glove to touch the canvas. Upon seeing this, referee Richard Steele quickly moved in and administered the mandatory eight-count, transforming a round Chacon probably lost into one he had won.

Boza-Edwards opened Round 2 on the attack and the first two minutes saw the challenger fire dozens of power punches at Chacon, who was content to respond with counters while resting his back on the neutral corner pad. One of Boza-Edwards’ punches opened a small cut over Chacon’s left eye, the same eye that was injured nearly two years earlier. However with 30 seconds remaining in the round, Chacon connected with a flush right to the jaw that drove Boza-Edwards to the canvas. Unlike the first round knockdown that appeared to be as much slip than a legitimate trip to the floor, this one was beyond dispute. Chacon didn’t have enough time to finish the job but for the second consecutive round, he turned a losing hand into a winning one, which seemed to be the theme of this, the autumn of Chacon’s boxing life.

Round 3 was the reverse of the first two as the counter-punching Chacon appeared to control the action only for Boza-Edwards to catch lightning in a bottle with a scorching left cross that knocked the off-balanced champion on his behind. A smiling Chacon sheepishly regained his feet, gestured as if to say, “Shucks, he got me,” then flashed an “I’m OK” nod at the NBC broadcasting team of Marv Albert and Dr. Ferdie Pacheco. Chacon then proved it by trading evenly with the challenger for the final minute of the round.

Bloody but unbowed, Chacon continues swinging vs. Boza-Edwards during their heated rematch. (Photo by The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

An already intense affair escalated at the start of Round 4 as the pair swapped heavy punches as if the result hung in the balance then and there. But neither man could be expected to maintain this burnout pace and soon they settled into a pattern that saw Boza-Edwards advancing and Chacon acting as the circling counterpuncher. Expert corner work kept Chacon’s bleeding to a minimum and his surgically repaired nose remained free of crimson but Boza-Edwards’ crisp right hooks and knifing lefts threatened to change all that. The vigorous combat extended several seconds past the bell and it took Steele as well as a Boza-Edwards corner man to restore order. True to their natures, both issued immediate apologies.

The handiwork of Chacon’s plastic surgeon was undone early in the fifth, and the constant dabbing at his face told Boza-Edwards – and everyone else – that he was bothered. Moreover the puffiness around the left eye that was so evident in Fight One was back in Fight Two and Boza-Edwards’ sustained attack was more than enough to win him the round.

Chacon’s troubles worsened in the opening seconds of the sixth when a left cross caused blood to cover the area around the champion’s right eye, a far more serious injury than the one near his other orb. This development set off an alarm inside Dr. Pacheco, one that told him that Chacon was careening toward potentially permanent damage. This fear, surely rooted in the emotions that prompted him to resign as Muhammad Ali’s personal physician after “The Greatest” refused his advice to retire after the Earnie Shavers fight, would color his commentary for the rest of the broadcast.

“Now the right side of Bobby Chacon’s brow is beginning to bleed,” Dr. Pacheco said. “That means he has cuts over the right and left (eyes) and he has trouble with his nose. Nobody can take this kind of punishment without having some type of injury inflicted. Unless Bobby Chacon can get very lucky with Boza-Edwards, the handwriting is on the wall. Many people felt it was too soon after that devastating fight with Bazooka Limon – and it might well be – the difference is that Boza’s a non-stop punching machine whereas Chacon is trying to get in his one or two lucky shots.”

The increasing blood masking Chacon’s face only heightened the picture of hopelessness Dr. Pacheco painted, a picture that was furthered when he declared that “Bobby Chacon needs a miracle to win this fight; it’s only the sixth round but the result is written on his face already.”

Based on Dr. Pacheco’s comments, NBC decided to skip the commercial break and focus on the action in Chacon’s corner in case the ringside physician, Dr. Edwin “Flip” Homansky, stopped the fight between Rounds 6 and 7. The sight of Chacon’s face only enhanced that possibility, for Boza-Edwards’ attack worsened the cut over the left eye and turned his visage into a crimson smear.

Dr. Homansky asked Chacon if he could hear him, at which the fighter briskly answered, “I hear you.” He left the corner following a brief check but Dr. Pacheco interpreted the episode in much more apocalyptic terms: “The doctor just said that if this keeps on going we’re going to stop it; what he’s saying is, ‘You got one more round and after that, it’s curtains.’ ”

Chacon’s blood had turned Boza-Edwards’ trunks from a dazzling white with a black stripe to one sporting splotches of red and because he had good reason to believe the fight could be stopped by one strong attack, Boza-Edwards forgot all about pacing and gunned for the win. Meanwhile Chacon, who was convinced he was fighting his last round, revved up his attack in Round 7. A little more than a minute into the session, Steele called a “time out” and asked Dr. Homansky to examine Chacon.

“I’m going to let it go right now but it ain’t going to go much longer,” Dr. Homansky said. “Let him fight.”

“This is the last round of this fight,” Dr. Pacheco declared.

A concerned Dr. Ferdie Pacheco co-commentated Chacon-Boza-Edwards II with Marv Albert on NBC.

Realizing Dr. Pacheco could be right, Chacon blazed away with both fists and the analyst wondered why Boza-Edwards was exchanging with him, for, in his eyes, all he had to do was see out the end of the round and the championship was his.

For Chacon, not only was this a title fight against Boza-Edwards but also a race against time. The urgency level was cranked up several notches for the fighters, for the live audience and for viewers like me whom awaited the next plot twist. The fighters spent the final minute engaging in one of the longest and fiercest exchanges yet. In their minds, the fight had mere seconds remaining and both were willing to empty their tanks.

Once again, the network decided to stay with the fight between Rounds 7 and 8 in anticipation of the fight being stopped. All eyes – and ears – were on Dr. Homansky, who wasted no time in terms of reporting the decision that had been made.

“All right, I talked to the head doctor and we’re going to let it go,” he said.

“Yeah?” Chacon asked.

“You can keep going…do you want it? Do you want to keep on fighting?” Dr. Homansky asked.

“Yeah!” Chacon answered.

While Albert was surprised by the 180-degree turn, Dr. Pacheco, who had Boza-Edwards ahead 69-65 on his scorecard, was both disappointed and deeply concerned.

“Oh, what a shame,” he said. “Both eyes are ripped; his nose is bleeding and while his corner men are brave and, no question about it, Chacon is very brave and this is a very tough fight but he’s so far behind and they gave him one round to do what he wanted to and he couldn’t (do it). I really, really would like to see this fight stopped right now.”

As Chacon and Boza-Edwards battled on, Dr. Pacheco and Albert were engaged in their own give-and-take. As the analyst decried the punishment Chacon received in the Limon bout, Albert pointed out that Chacon won the fight and became world champion. “Unfortunately your body and your brain don’t know that,” Dr. Pacheco replied.

Moments later, Steele called for yet another medical time-out.

“I don’t know about this; that many time-outs, that many things…what do they need?” Dr. Pacheco said with disgust dripping in his voice. “Let’s listen.”

As Homansky looked at Chacon’s injuries, he asked, “You wanna still fight, Bobby?”

That question transformed Dr. Pacheco’s tone from concern to outrage.

“What’s he asking him, ‘Does he wanna still fight’ for?” he said in disbelief. When Dr. Homansky allowed the fight to continue following a brief check and an “I’m all right” from Chacon, Pacheco posed a pointed question: “I can’t see that…I can’t see that. What is a doctor asking a boxer if he still wants to fight? What does he think he’s going to say, ‘No’? Especially [from] a man of the valor and proven ability of Bobby Chacon? All they are giving Chacon is a lot of rest and a lot of time.”

There was never any quit in Chacon, who would not be denied in his rematch with Boza-Edwards. (Photo by The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

Meanwhile Boza-Edwards – who was becoming a secondary character amid all the drama surrounding Chacon – pressed on. But his gas tank was depleting and Chacon, sensing this, somehow upped his attack. As he rattled several combinations off Boza’s frame, the pro-Chacon crowd came alive with chants of “Bob-bee! Bob-bee!” Meanwhile a picture-in-picture camera kept an eye on Dr. Homansky, who was seen consulting with a colleague. Convinced the fight would be allowed to continue, NBC cut away for a commercial break.

As the network returned to the fight, a plastic surgeon was seen telling Chacon that the ninth was going to be the last round of the fight, a declaration that was music to Dr. Pacheco’s ears. Still, he added “but they told him ‘one more’ two rounds ago.”

The fighters exchanged heavy punches at close range, with Boza-Edwards first getting the edge, then Chacon moments later. As the round neared its end, Chacon summoned a huge rally that energized the live crowd and had Boza-Edwards looking more like a spent force. That rally also imposed an ethical dilemma on the ringside physicians: Do they live up to the declaration that was made between rounds and stop the fight despite Chacon’s inspired rally or do they grant the defending world champion another round?

“That’s what is going to make it so difficult to stop this fight,” Dr. Pacheco said. “Bobby’s always full of life at the end.”

“This crowd is not going to react well if the bout is stopped,” Albert added.

As the bell to end Round 9 sounded, NBC again chose to show the happenings in Chacon’s corner, prompting both commentators to state that “This is going to be interesting.”

With Chacon and his corner people pleading with both doctors, Dr. Homansky administered a test to the champion’s eyes, a test that he ended up passing.

“The doctor has been examining his eyes with an ophthalmoscope to see if he is reacting, if there is any brain damage, if there is any kind of damage at all,” Dr. Pacheco reported. “He didn’t see any, and, by golly, they’re going to let it go.”

At this point, Albert, a Hall of Fame NBA broadcaster who doesn’t attempt to play a doctor on television, nevertheless asked a perceptive medical question of Dr. Pacheco: “What can (Dr. Homansky) tell here off a simplistic observation concerning brain damage?”

Dr. Pacheco, perhaps chastened by his colleague’s query as well as by the realization that he had just engaged in sensationalism that would compromise his credibility as a medical expert, quickly corrected himself by sputtering, “He can’t…at all…anything.”

With that, Round 10 commenced. And once it began, Chacon, given yet another reprieve, shifted to a higher gear while Boza-Edwards, again denied another chance to win the title inside the distance, doggedly pressed on. Chacon’s blows were delivered with more zip, better sharpness and more impact than was the case in the last several rounds, the effects of which could be seen in the challenger’s shaky legs. Chacon drew strength from Boza-Edwards weakness and the vicious circle resulted, for the champion at least, in a circle of viciousness.

Even as Albert marveled at Chacon’s resurgence, Dr. Pacheco dwelled on the fact that the champion lacked the energy to keep his hands up at all times but even he acknowledged the challenger’s growing exhaustion.

Chacon’s corner received yet another visit between Rounds 10 and 11 and had the fight been scheduled for 15, it might have been stopped long ago. But because the WBC reduced its championship fights to 12, it was, at this point, easier to justify allowing this high-risk fight to continue.

With Chacon propped against the ropes, he felt comfortable enough with the situation to pot-shot Boza-Edwards with long-range punches while slipping the majority of the challenger’s offerings. Despite looking like they were red-lining in terms of their stamina, Chacon and Boza-Edwards continued to press their respective accelerators to the floor. However the champion – who was counted out more than once in this fight – fared better in the 11th round.

With three minutes remaining, no one was certain who had the edge but Chacon knew he had no room for error and just like he did in the final round of the Limon fight, he punctuated his effort with a savage combination that put Boza-Edwards on the floor. Just as he had after flooring Limon, Chacon leaped forward into the ropes in celebration. Boza-Edwards regained his feet and for the next two minutes, he gunned for the inside-the-distance win. The ultra-confident champion banged in ceaseless combinations – and even threw in a “Chacon Shuffle” – but the Ugandan’s fighting spirit was enough to keep him upright until the final bell.

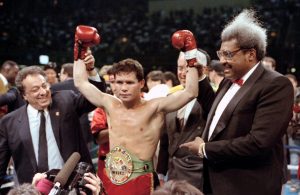

The decision was unanimous – and, given how the fight was portrayed by Dr. Pacheco – stunning. Dave Moretti saw the fight a surprisingly wide 117-111 while Duane Ford (115-113) and Lou Tabat (115-112) viewed a much smaller margin for the winner…and still…champion. At least for now.

For this single father of three children aged 7, 9 and 12, the motivations for his superlative effort were obvious.

“I’m just fighting for my three kids,” he said. “My wife couldn’t wait, so everything I do now is for my family. This is my last year of fighting and I want to make some money. Bring on Camacho. I’d like to fight the ‘Macho Man.’ It’ll be East against West. Let him come to Sacramento. After that, I think I’d like to go after Ray Mancini. That’ll be a very tough fight. After that, I plan to get out. I was a fool when I was a kid but I’ve grown up some and I’m more serious.”

“Boy, what a fight!” Chacon concluded. “Wish I could’ve seen it.”

According to the New York Times, Boza-Edwards almost didn’t. The challenger was asked by a female guard for his ticket. When Boza-Edwards replied he was fighting in the main event, she replied, “That’s what everybody says,” before refusing entry. Fight manager and film collector Jimmy Jacobs, a friend of Boza-Edwards’ manager Mickey Duff, ran inside and secured a $75 ringside ticket that the fighter used to gain entry.

Besides the fighters, however, the man of the moment was Dr. Homansky, who explained his actions to Albert.

“Never was I about to stop the fight,” he said. “The whole point here was that his vision was not impaired. There was going to be no permanent disability from his injury. Whether it’s a cosmetic problem, I think Bobby can handle that and I have no compunctions about what happened and would do the same thing again. His vision, his eyesight, will be fine after this.”

When Albert confronted him about his repeated assertions that the fight could be stopped, Dr. Homansky, who was in his third year as a ringside physician, said the following: “The cut looked like it was such that if he took more punishment it would open up. It was not opening up. That was the key. About the sixth or the seventh round, it looked the worst it was going to look. It did not open any further; I was surprised at that. It was a competitive fight. He’s the champion; he deserved his chance and he got it.”

Dr. Homansky wasn’t the only person outside the ring whose performance was criticized. While some understood Dr. Pacheco’s concern for Chacon’s well-being due to his medical background, others were offended by the overwrought nature of his call, a call that inspired some to dub him “The Fright Doctor.”

“No one in Boza-Edwards’ camp complained about the decision yet co-commentators Ferdie Pacheco and Marv Albert – the duo that hyped Larry Holmes against Lucien Rodriguez – ranted foolishly throughout the nationally shown telecast,” wrote THE RING’s Christopher Coats. “Despite the fact that Chacon’s cuts were inspected by two doctors and his personal plastic surgeon, Pacheco rendered his medical opinion from his chair and all but demanded that the fight be stopped. When referee Richard Steele twice halted the bout, Pacheco honked, ‘All they’re doing is giving Chacon some extra time to rest.’ As if Boza-Edwards was doing construction work while Chacon’s eyes were being inspected! Pacheco continually put both feet in his mouth to serve his own ego.”

Chargin immediately forwarded a $1 million offer for Chacon to face the second-ranked “Macho Man.” According to the Times story, Chacon said he was willing to drop his purse to $900,000 but that he would never, ever fight for Don King.

However King asserted his contractual claim and, on June 28, 1983, the WBC stripped Chacon of its championship, saying he had violated “at least nine” rules, most of them relating to timely defense of the title. Chacon continued to refuse a Camacho fight as promoted by King and sought court approval to have the fight promoted by Chargin. When he couldn’t gain that approval, the resulting stalemate resulted in Chacon being relieved of his belt.

This development so outraged me that I fired off a letter to Boxing Illustrated, a letter that was printed in the November 1983 issue. This marked the first time that my name had ever been seen inside a boxing magazine but while my anger over the WBC’s actions was evident, my ability to fully express it was lacking. The following is the entirety of my letter:

“Something has to be done about Bobby Chacon’s title being stripped by the WBC. It was very wrong. Chacon won the title in the ring and defended it against the number-on contender. What more can you ask of a champion? Doesn’t it state in the WBC rules that a champion must defend his title against the top contender every six months? Well, Chacon beat Boza-Edwards, so they have no right to ask him to do anything for six months.

“What the WBC has done to Chacon is sadly typical of the self-serving attitude they have cultivated for years.”

Not exactly Bernie-worthy prose, but at least I got my point across.

As an adult, I see merit in both sides of the argument. On the one hand, Chacon should have never been penalized for upholding the ideal of fighting a legitimately dangerous No. 1 contender such as Boza-Edwards but I also see why King reacted the way he did and why the WBC ruled as it did. Chacon knew well what he was getting into when he signed with King: Yes, he got the title shot he wanted and he cashed in on it but, now that he was champion, he was obligated to live up to the terms of the agreement and those terms included the promoter being given the power to choose his next three opponents. For better or worse, King wanted him to fight Camacho for a relatively paltry purse and, like it or not, Chacon’s actions, while understandable, represented a breach of contract. And while the WBC had long been maddeningly inconsistent with the application of its rules, it was within its rights to strip Chacon once it became clear that a deal to stage Chacon-Camacho with King as the promoter would not happen. Even so, my sympathies remained with Chacon, one of history’s greatest comeback stories and one of the sport’s most beloved warriors.

Just nine days after Chacon was stripped, Camacho won the vacant belt by steamrolling the painfully slow Limon in five rounds before a rapturous crowd inside a sun-drenched Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan. Chacon went on to challenge WBA lightweight titlist Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini in January 1984 but was stopped in three high-octane rounds while Boza-Edwards lost a 10-round decision to Rocky Lockridge on the Aaron Pryor-Alexis Arguello II undercard in September 1983, then went 6-0-1 in his next seven fights before meeting Camacho for the Puerto Rican’s WBC lightweight title. Boza-Edwards, dropped in Round 3, went on to lose a dreary decision and only fought twice more. The final fight of his career was a fifth round TKO loss to WBC lightweight titleholder Jose Luis Ramirez in October 1987.

Boza-Edwards’ final record was 45-7-1 (with 34 knockouts) while Chacon’s ledger read 59-7-1 (with 47 KOs). It can be argued that both men left the last vestiges of their best selves inside the ring at Caesars Palace and while only Chacon walked out of that ring as a winner, sentiment remembers them both as champions, for THE RING deemed their battle as its 1983 “Fight of the Year.” In a wider view, however, the victor and the vanquished lived up to the ideals embodied by a Warrior King.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 16 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.

THE FOUR KINGS SPECIAL now at

THE RING SHOP (Click Here)