When Eras Collide: The 40-year anniversary of Leonard-Benitez

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Ring Magazine.

The left hook came out of nowhere, sharp and quick, with only 30 seconds remaining in the 15th and final round. It was thrown by the 23-year-old challenger, Sugar Ray Leonard, and grazed the temple of WBC welterweight titleholder Wilfred Benitez. For most of the round, they’d been head-to-head, ripping at each other with cruel liver punches and uppercuts. The hook surprised Benitez. His body wobbled before he fell to his knees.

It was the second time he’d been knocked down that evening. He popped back up immediately, shook his head, strolled away from referee Carlos Padilla and approximated the look of a man in control of his senses. The bout had been a tactical one, but both fighters wore the marks of a street brawl: Leonard’s face was bruised, his lips swollen; Benitez’s forehead was sliced down the middle, as if he’d been tapped with a small cleaver. Benitez took the eight count with his back to Padilla. He nodded at ringsiders, his white mouthpiece bared. Leonard leaned against a neutral corner. Sensing the fight was his, he smiled wearily.

It had been an intense contest, each round humming with a kind of pulsing danger. “From a technical standpoint,” said Angelo Dundee, Leonard’s adviser, at the press conference afterward, “there was more done in this fight than I’ve seen done for a long time.”

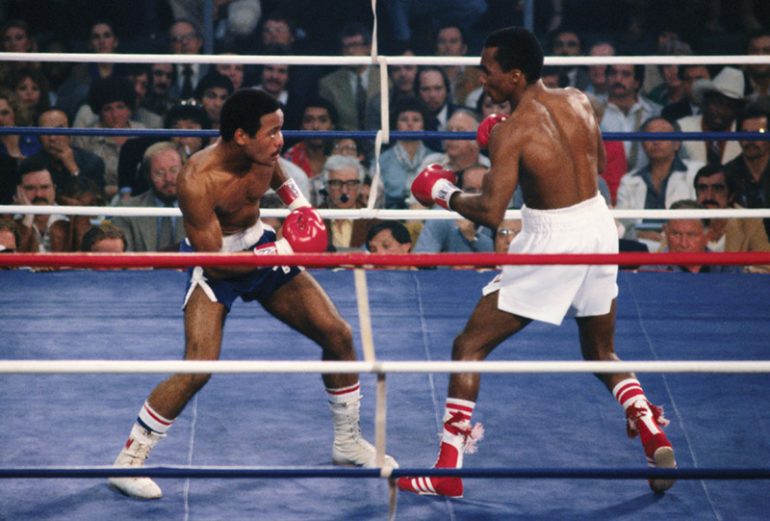

Ray Leonard proved to be more than a talented Olympic champ and media darling against Wilfredo Benitez. (The Ring Magazine)

Though it heralded the arrival of Leonard, the night he defeated Benitez didn’t have the cachet of Sugar Ray’s future bouts, nor did it yield memorable catchphrases like “No mas” or “You’re blowing it, son.” Yet, it was an event that had been hyped to the skies, an encounter between two massively talented future Hall of Famers, each aware that a single mistake could cost them the fight.

The 4,600 customers gathered that night in Las Vegas to witness the richest non-heavyweight bout up to that time – Leonard made $1 million, defending champion Benitez a shade more – had been lured into Caesars Palace like prospectors to a gold rush, all adding to the growing notion that Leonard was the new face of boxing. For a rare time in history, it appeared that the sport’s biggest name was now a competitor far below the heavyweight class. “Once in a great while, a fighter comes along who changes all the numbers,” said promoter Bob Arum. Indeed, Leonard had already earned a few million dollars without even fighting for a championship. Now, with Benitez bloody and stunned, it appeared Leonard was about to win his first professional title.

‘Once in a great while, a fighter comes along who changes all the numbers.’

Benitez knew the bout was slipping away, so he’d come out for the 15th like a gunslinger. This wasn’t his preferred way of doing things, but he began lashing at Leonard, holding his own until caught by Leonard’s short left. In the second before Benitez fell, he looked up at Leonard. His face showed panic, confusion, disappointment. It was the sort of intimate moment that can happen in boxing but few other sports, when you can make eye contact with the person who has come to take away your livelihood. When Benitez rose, Padilla asked if he was OK. Benitez nodded. Padilla waved the fight on. Leonard rushed in, whipped a right lead. Benitez tilted his head just enough to make Leonard miss, but Leonard followed with a left uppercut that cracked against Benitez’s face. The champion wavered. For the first time in the fight, if not his career, he seemed utterly without answers. The challenger threw three more punches, all missing. Had one of them landed, Benitez might’ve fallen out of the ring. Padilla moved in.

It was Friday night, November 30, 1979, 40 years ago, and Las Vegas was hosting not a mere changing of the guard, but the beginning of a significant new era. The 1970s were ending; the Ali epoch was fizzling out, and with it was going the politics, the anger and the grief of Vietnam. The 1980s, a time of greed and fun and glitz, were about to kick off. Though Leonard had won a gold medal at the 1976 Olympics, he was truly an athlete of the ’80s, encapsulating much that those years would entail. Leonard was a new kind of fighter, glowing with business savvy as well as ring savvy. It became common to say Leonard would one day be CEO of a Wall Street firm.

He’d arrived in Las Vegas like a visiting raja as praise and speculation swirled. He posed for pictures with Cher and spoke earnestly to the press about his desire to be special. The general impression was that he was a refreshing character, something sorely needed in boxing. Ali’s career had been a circus, wrote Dave Kindred of The Washington Post, while Leonard was “a picnic in the park.” Dundee, Ali’s old trainer, was asked by Red Smith of The New York Times to compare the two. “I can’t compare him to Ali at 23,” Dundee said. “Ali was too intricate, too many interests. This kid is home cookin’.” Cus D’Amato, still a few years from unleashing Mike Tyson on the public, proclaimed Leonard “the best finisher since Joe Louis.” The hoopla sounded like nothing less than a coronation.

Because of his camera-ready grin, his articulate manner and the fact that he sometimes appeared in public wearing a yachting cap, some of Leonard’s contemporaries dismissed him as a media creation. He was not. He was a fighter. But whether he was heralded or scrutinized, he remained a mystery. “Leonard is like a beautiful woman,” said Benitez’s manager, Jim Jacobs. “You never know what she is concealing. We’ll know after this fight what Leonard may be hiding.”

Benitez, meanwhile, had started his career as a wunderkind, a teen prodigy who won the WBA junior welterweight title at age 17 – he remains the youngest fighter to win a major boxing title, and his achievement is unlikely to be challenged – doing so against the revered Colombian star Antonio Cervantes. At 21, Benitez was Leonard’s junior by two years but was already viewed in boxing circles as a sort of living legend. He was notorious for slacking off in the gym but was still able to outclass most opponents. Teddy Brenner, the Madison Square Garden matchmaker of the 1960s and ’70s, would say of Benitez, “At one time he was the best fighter in the world.” Still, Leonard was installed as a 3-1 betting favorite – strange, since he’d never even been past 10 rounds.

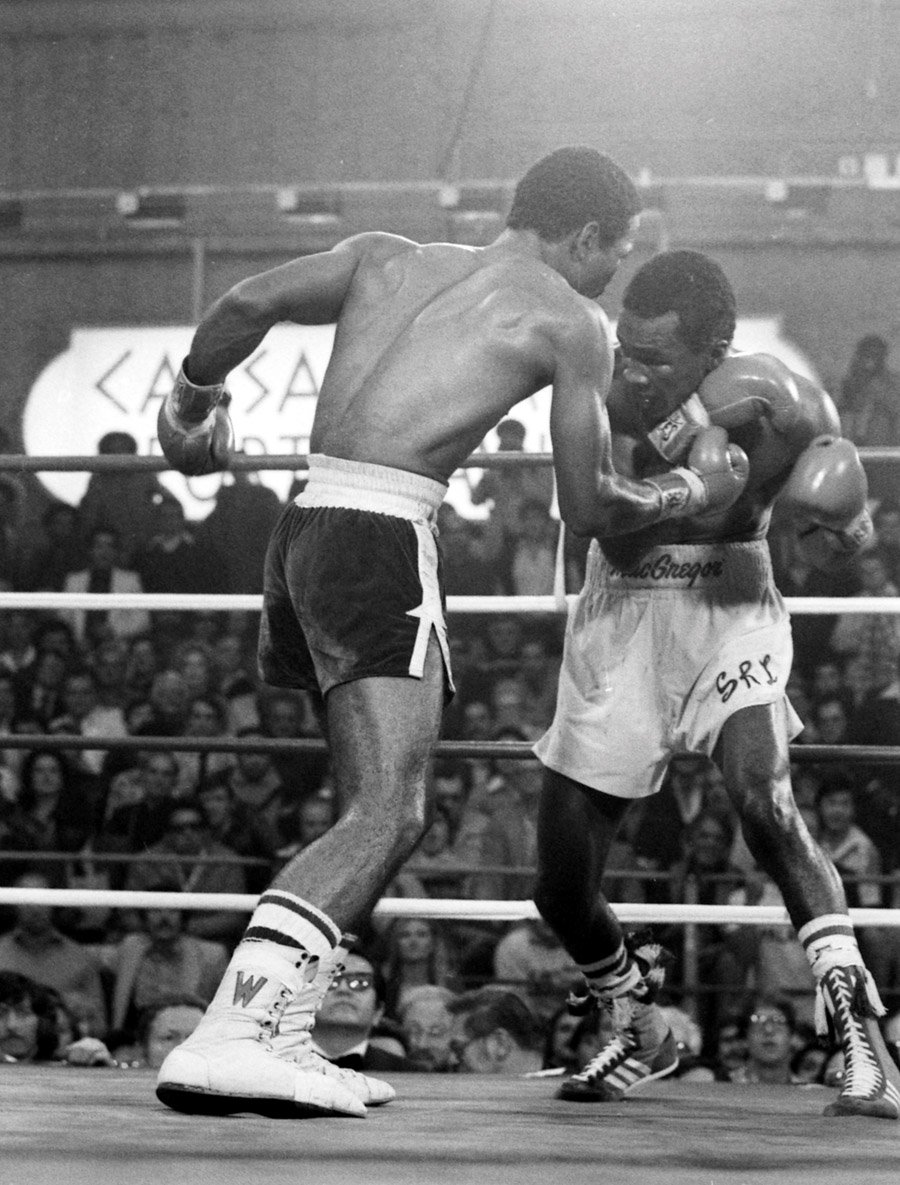

Ten months before he’d step into the ring against Leonard, Benitez faced incumbent welterweight champion Carlos Palomino in Puerto Rico:

The oddsmakers may have been influenced by Benitez’s ongoing trouble with his father and original manager, Gregorio. Benitez was puckish, impulsive and immature. He wanted independence, but he wasn’t emotionally equipped to handle it. He’d been in a boxing bubble since he was 7 years old. Benitez hired Jacobs to manage him just before the Leonard bout. Jacobs was an enthusiastic boxing man but couldn’t wrangle Benitez into the gym. Legend has it that Benitez trained no more than nine days for Leonard, the most high-profile opponent of his life.

Leonard, meanwhile, studied Wilfred’s style and developed a nice strategy. “I would attack from every conceivable angle,” he said later, “changing speeds the way a pitcher does on the mound.”

And for the first few rounds, Leonard’s game plan was perfect.

After an intense mid-ring staredown, Leonard took control of the first round, rocking Benitez with a left hook followed by a right hand. Unable to land a follow-up, Leonard calmed down and went to work methodically – Ali had advised him before the bout to be serious, to not showboat – and in the third he landed a sudden jab that put Benitez on the seat of his trunks.

The quick knockdown motivated Benitez. In the fourth and fifth, he baffled Leonard with his own left jab – an evil, nasty thing that flicked like a switchblade. Leonard tried to fire back, but Benitez was elusive. This was the gleeful Benitez, the childlike genius who had left so many opponents swinging at nothing, the one known as “El Radar.”

By the seventh, though, the momentum changed again. A clash of heads had left Benitez cut. Worse, his left hand was bothering him. Leonard stunned him in the ninth and punched his mouthpiece loose in the 11th, a feverish round where Leonard pinned Benitez on the ropes and pummeled him. The 12th, 13th and 14th were close, played out like a sort of fencing match between two master duelists. Leonard was up on the scorecards, but as the momentous 15th began, Dundee told him otherwise. It was, Dundee said, “a very, very close fight. Go out there and fight like an animal.” As he’d do many times in the coming years, Leonard put on the razzle-dazzle finish.

How fierce the two of them were. Benitez ignored the soreness in his left hand and went after Leonard. Standing as flat-footed as Tony Galento in a New Jersey tavern, he put aside his cleverness and rumbled. In a way, it was Benitez’s shining hour, right up to the time Padilla stepped in and ended the bout with only six seconds to go. “Maybe now,” cried ABC’s Howard Cosell, “they won’t call Sugar Ray Leonard a hype!” As new champion Leonard leapt into the arms of his handlers, Benitez looked at Padilla with what the United Press called “a startled look of disbelief.”

A blast of cheering followed, undercut by an ominous drone of booing. Many felt the stoppage was unnecessary and that Benitez had been denied the dignity of hearing the last bell. Benitez, having just experienced his first loss as a professional, didn’t gripe. In the middle of the mayhem that broke out in the ring, the boxers embraced.

There were rumors in Las Vegas that Padilla stopped the fight because a certain gambler had wagered $50,000 that the bout would end by KO. The story held no water – Padilla could’ve stopped the bout in the 11th when Benitez was on the ropes and had lost his mouthpiece. Still, it wouldn’t be the last time the cynics reared up after a Leonard fight.

That night, Leonard skipped his victory celebration and returned to his suite at Caesars. His body beaten to hell, he spent an hour soaking in a bathtub. His reflection in the bathroom mirror was ugly, haunting. Indeed, it was already a cliche to call him the next Ali. Yet, a less than devastating puncher like Benitez had left him aching in a bath. As he noted in his memoir, The Big Fight, Leonard thought about retiring. He wondered about brain damage.

Thus began “The Ray Leonard era,” a period of roughly seven years where this boyish welterweight from Palmer Park, Maryland, would be boxing’s greatest draw. Leonard never quite replaced Ali, though his career was dramatic and often inspiring. Outside of boxing, Leonard dabbled in television and promoting. To the surprise of some, he never became a boardroom leader. Instead, his post-boxing years have been typical of a once-famous fighter. For a while, it seemed his legacy had less to do with his fights and more to do with the way he’d controlled his career. Leonard showed future fighters that they didn’t have to be at the mercy of managers and promoters. Not even Ali had enjoyed such control, and no fighter since Ray Robinson, the first “Sugar,” had so unapologetically taken the reins of his destiny. But unlike some who have followed, Leonard almost always put on a good show. Looking back, his fights seem like small masterpieces, sporting events that bled over into the popular culture.

No one wept for Benitez that night in 1979. He was still young. But his future was grim. He quit boxing at 37 and ended up back in his homeland of Puerto Rico, enfeebled, under his mother’s care. Leonard visited him some 30 years after their bout. Benitez was asked if he recognized the man in front of him.

“No,” Benitez said. “But I know he beat me.”

MORE: Incredibly, the card featuring Leonard-Benitez also included a fight between unified middleweight titleholder Vito Antuofermo and Marvelous Marvin Hagler.

READ “Leonard-Benitez and Antuofermo-Hagler I: A Memorable Night at Caesars” by Doug Fischer, published in 2014.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.