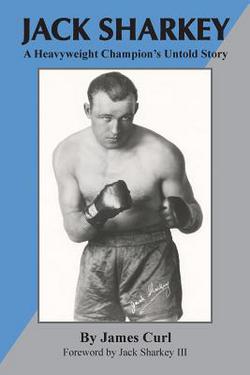

Literary Notes: ‘Jack Sharkey’

For more than a century, the heavyweight championship was the most coveted title in sports. But there was a strange interregnum between Gene Tunney and Joe Louis when five men played musical chairs with the throne and its luster dimmed.

For more than a century, the heavyweight championship was the most coveted title in sports. But there was a strange interregnum between Gene Tunney and Joe Louis when five men played musical chairs with the throne and its luster dimmed.

Four of these men have taglines that identify them. Max Schmeling became a symbol of Nazi Germany. Primo Carnera was the mob-controlled giant. Max Baer was a hard-hitting playboy. James Braddock was the impoverished dockworker struggling to survive during The Great Depression.

Jack Sharkey is virtually unknown.

“Jack Sharkey: A Heavyweight Champion’s Untold Story” by James Curl (Win by KO Publications) is the antidote to that malady.

Joseph Zukauskas learned to box in the United States Navy. He changed his name before his first pro fight in 1924 as a tribute to Jack Dempsey and Tom Sharkey.

“Sharkey,” Curl writes, “was a fighter who ran hot and cold and gave erratic performances throughout his career.” His final ring record was 37 wins (13 KOs), 13 losses, and 3 draws. The most notable opponents he faced were Harry Wills (WDQ 13), Dempsey (LKO 7), Tommy Loughran (WKO 3, LSD 15), Schmeling (LDQ 4, WSD 15), Mickey Walker (D 15), Carnera (WUD 15, LKO 6) and Joe Louis (LKO 3).

Curl blends extensive newspaper fight reports with other sources. One of his best accounts is of Dempsey-Sharkey (contested before 80,000 fans at Yankee Stadium in 1927). Dempsey went flagrantly low often and hard. Finally, Sharkey turned to the referee to complain, and the Manassa Mauler knocked him out with a picture-perfect left hook to the jaw.

Years later, Sharkey recalled, “When Dempsey hit me, it was like someone dumped a load of concrete over my head. I never thought a man could hit so hard. I’ve felt that punch for thirteen years.” At age 85, he said of that night, “Dempsey broke every rule of the prize ring. He hit me in the nuts all night long.” Asked if he was still bitter about it, Sharkey answered, “Nah, he saw an opening and he took it.”

Sharkey’s first fight against Max Schmeling (in 1930, when Schmeling won the vacant heavyweight title in front of 85,000 fans at Yankee Stadium on a questionable disqualification) is well told. There’s curiously little material in Curl’s book on Schmeling-Sharkey II, when Sharkey captured the crown on a 15-round split decision two years later.

Then came Sharkey’s first title defense: a one-punch sixth-round knockout loss at the hands of Primo Carnera in a bout that many observers thought was fixed. Curl presents both sides of the “fix” debate, giving the last word to Sharkey who, nearing the end of his life, declared, “I’d never have done anything like that. I was raised Catholic. I was raised to be honest. I was on top of the world. Why would I purposefully lose?”

Asked what it felt like to lose, Sharkey responded, “It’s a terrible feeling. You devalue yourself. You don’t want to see anyone. You just want to hide.”

The last fight of Sharkey’s career was a third-round knockout loss to a young Joe Louis.

“Youth was served tonight,” Sharkey said afterward. “Good luck to him. He’s a good fighter, better than I am. Whether he’ll be as good as I was tonight [when he’s] thirty-four remains to be seen.”

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at [email protected]. His next book (“A Hurting Sport”) will be published by the University of Arkansas Press.