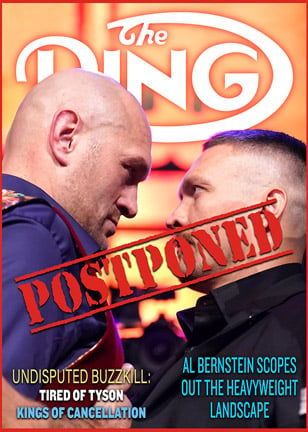

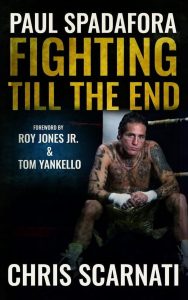

Fighting Till the End

Paul Spadafora captured the hearts and imagination of his native Pittsburgh as he climbed the lightweight rankings during the late 1990s. The crafty, rugged southpaw won the IBF belt with an upset unanimous decision over Israel Cardona in 1999 and went on to become a staple of ESPN’s and HBO’s boxing programming as he entertained hardcore fans with memorable title defenses against Ring-rated lightweights such as Victoriano Sosa, Angel Manfredy and WBA counterpart Leo Dorin during the early 2000s.

However, anyone remotely familiar with Spadafora’s career knows that his hardest fights occurred outside of the ring due to drug addiction, which threatened to end his life even as he compiled an unbeaten record over 49 professional bouts. Chris Scarnati’s book Fighting Till the End candidly examines Spadafora’s many ups and downs over the past 25 years as the boxer-turned-trainer struggled to conquer his demons and come out on top.

However, anyone remotely familiar with Spadafora’s career knows that his hardest fights occurred outside of the ring due to drug addiction, which threatened to end his life even as he compiled an unbeaten record over 49 professional bouts. Chris Scarnati’s book Fighting Till the End candidly examines Spadafora’s many ups and downs over the past 25 years as the boxer-turned-trainer struggled to conquer his demons and come out on top.

Published by Creative Text Publishers, LLC and released in November 2023, Fighting Till the End is the official biography of former IBF lightweight champion Paul “The Pittsburgh Kid” Spadafora. The book is available on Amazon,BarnesandNoble.com and Walmart.com, with an audiobook accessible through SoundCloud and iTunes.

The following chapters are reprinted courtesy of Scarnati.

***

Disappointment, drug abuse, and recovery

In the end, Floyd Mayweather Jr. killed Paul’s dream without throwing a single punch.

“My fans have been waiting long enough,” he Tweeted. “Floyd Mayweather vs. Victor Ortiz. Sept-17 2011 for the WBC World Championship.”

Paul imploded. “All year long, I was told I’m fighting Mayweather,” he said. “I had went (almost) a year without fighting anyone. I didn’t even have enough money to buy a soda. I thought, ‘No Mayweather fight, I’m done.’”

And by done, Paul meant he was ready to die. He hit the streets, scored his first ounce of heroin, snorted it all in an alley, and waited to take his final breath on a friend’s bed.

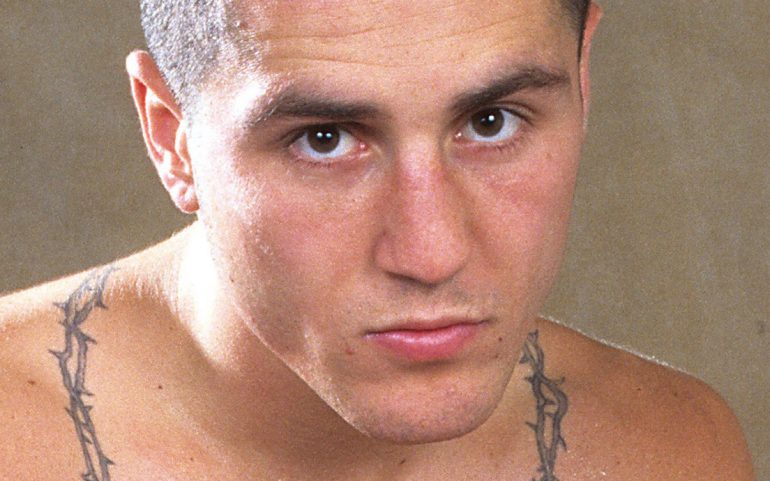

Paul Spadafora wearing his IBF lightweight title in 1999. (Photo: The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

Paul was found unresponsive and rushed by ambulance to Allegheny General Hospital. Doctors revived him and he was released, but the overdose did not change his emotional state. He hid in the shadows of abandoned buildings that lacked heat, running water, and electricity for weeks. He used coke. When that ran out, he smoked crack.

During weaker moments, he clutched an AK-47 against his lap and cried himself to sleep as he entertained sinister scenarios. “I was ready to rob and kill a drug dealer,” Paul said. “I had it justified in my mind.”

He suppressed that whim but no longer had qualms about voicing his irritation with [his promoter Mike] Acri. “(Paul) wanted me to stay with him but wanted to get rid of Mike, and I wasn’t going to leave Mike,” [Spadafora’s manager Al] McCauley said. “(Acri) was the one who put Paul into position to get another title.”

At that point, none of it mattered. Many months behind on child support payments, Paul continued using drugs and was arrested twice that fall for drunk driving. Gaunt, disheveled, and devoid of all hope, he figured it was only a matter of time before a cemetery plot beckoned his name.

Fortunately for Paul, he was blessed to have friends in high places who wanted to see him reclaim control of a life and legacy they believed was worth saving.

Marco Machi, owner and lead trainer of The Exercise Warehouse in Bloomfield, took pity and persuaded Paul to work at his gym. In exchange, Machi permitted him to stay in an empty apartment on the facility’s second floor. The move was not a final remedy but a crucial, preliminary step that forced Paul to slow down. It also facilitated visits with his son [Geno], who was still under the primary care of a foster family. “Geno went to Immaculate Conception (School), and when it would let out, I would pick him up and take him to my crib,” he said.

Paul’s demeanor improved further that winter when he was approached by Ray Ventrone, a pal affiliated with the local chapter of the Pittsburgh Boilermakers Union, and presented with a paid sponsorship to attend Transitions Recovery Program. The posh drug and alcohol treatment center in North Miami Beach, Florida, served an upscale clientele that included Hollywood celebs and professional athletes.

The offer was too enticing to snub. “(Ventrone) told me, ‘I feel sorry for you. You were The Pittsburgh Kid, and you look bad. You need to get help,’” Paul said. “It was freezing outside. What else was I going to do.”

Paul flew to “The Sunshine State” and embarked on a seven-month cleanse that shook him to his core. As a boxer, he intrinsically kept his gloves elevated to protect himself. But at Transitions, he let down his guard and exposed his vulnerability. He unloaded anecdotes about his relationship with his dad, his day-to-day survival with a sex offender, the losses of [his amateur coach P.K.] Pecora and Pap [his grandfather, Geno Polecritti], his many arrests, the inexcusable morning he nearly killed [his girlfriend] Nadine [Russo], and his compulsive self-destruction. He left no stone unturned. “I had to sit in front of people and tell my life story,” Paul said. “I cried because it hurt so bad. I had to do some real soul-searching.”

Searching for a new promoter became an additional priority during his visit. But to accomplish that feat, he would first need to leave the one who had helped make him a world champion.

Read “Leonard Dorin: Best I Faced”

In the winter of 2012, Paul severed ties with Acri and McCauley (based on McCauley’s insistence that they came as a package). Paul loved them both and hated thinking about ending an alliance that spanned more than 15 years, but he saw it as his only option. “My mind was made up when I talked it over with my counselors,” Paul said. “I wasn’t going back to using heroin.”

Going back to the gym seemed more logical. Drumming a speed bag usually led him to better things. The staff at Transitions accommodated Paul by building him a personal training facility on its grounds.

And sure enough, the puzzle pieces for a second comeback organically fell into place.

It started when New Jersey-based manager Pat Lynch caught wind of Paul’s whereabouts. Lynch had steered the storied careers of world champions Al Cole, Ray Mercer, Charles Murray, and [Arturo] Gatti. In Paul, he saw an undefeated fighter with something left in the tank, so he sent Robert Ortense, a friend and fellow boxing buff who spent his winters in Florida, to meet Paul and investigate his availability.

Lynch’s interest waned upon hearing Paul was bound to McCauley. Ortense, oppositely, was enamored with Paul’s potential to make another title run. Sensing an opportunity to be part of something huge, he used Lynch’s connections to pair Paul with renowned trainer Mikey Rod and former IBF light welterweight and WBC welterweight champion James “Buddy” McGirt.

Within days, they would begin training in Fort Lauderdale. Within months, Ortense would unofficially assume the role as Paul’s new manager and score him a meeting with Wilfredo Negron (26-16-1, 19 knockouts) on a Tampa card with Fight Night Productions.

When Acri and McCauley expectedly objected and pulled the bout, Ortense brought Joe Horn into the fray.

Horn was an ex-cop turned attorney. He was also Ortense’s nephew-in-law through marriage and a boxing fan who was well-versed with Paul’s legal dossier. “Paul had a whole host of issues… a suspended license and open criminal cases,” Horn said. “I was brought on to be the guy with the mop and the bucket to clean up the legal aspect of all of this.”

Spadafora and his son, Geno, in the gym. (Photo by Nadine Spadafora)

Paul’s contractual restraints took precedence. After wrangling through preliminary resistance from the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission, Horn blocked McCauley that June from extending his agreement with Paul past its expiration date. Then, to further protect him, he and Ortense settled his tab. “(Paul) owed a lot in child support, and that gives the Commonwealth the authority to suspend a boxing license,” Horn said. “Bobby and I got him all caught up (with his payments), so there was nothing that would come back and bite us.”

Before divorcing Paul from Acri, Horn shopped around for a new promotional outfit, a process expedited by Paul’s eagerness to rehire Tom Yankello as his trainer.

Since prepping Paul for his last title defense, Yankello had made a sizeable splash in the boxing scene. In addition to guiding Monty Meza-Clay to an International Boxing Association (IBA) super featherweight championship, Yankello had come extremely close to coaching IBF heavyweight title challenger Calvin Brock and WBO cruiserweight title challenger Brian Minto to world titles. He was also in the process of training eight-time world champion Roy Jones Jr.

During a telecast, ESPN Boxing Analyst Joe Tessitore even sang Yankello’s praises. “If I were managing a fighter and needed a trainer who could take us all the way, Tom Yankello would be on my shortlist,” he declared. “What he does with his talent is very impressive. His passion and enthusiasm for the sport, and his commitment to his fighters, is as good as anybody’s.”

Paul had always been conscious of these virtues but was most interested in linking up with someone who understood him above all others. He reached out to Yankello during his stay at Transitions, and those old feelings were reciprocated. “Without boxing, I was going to die or be in jail, and you couldn’t let me alone with my boys down in (McKees) Rocks because I was always in trouble,” Paul said. “As a trainer, Tommy was like I was – obsessed with the game. And I knew if there was anyone I was gonna train with, it would be a guy that would let me box the way I knew how to box and would also be on me like flies on shit. That’s all I needed.”

Under Yankello’s recommendation, Paul signed with TNT Promotions, a burgeoning enterprise led by Troy and Tammy Ridgley, Yankello’s brother Mark, and advised by Jones Jr. “Paul was once at the top, and he could get back to the top with the right people around him,” Jones Jr. told Sports Illustrated. “Not many people would want to take a chance on him, but we’re willing to take that gamble and see what happens.”

Paul was anxious to prove TNT had played their cards correctly. He left Transitions that July and returned to Pennsylvania to train with Yankello for his first assignment – an August 18, 2012, welterweight matchup against Negron, the boxer he was initially booked to meet.

Acri sued Paul for violating their promotional contract, but Horn and TNT attorney Steve Toprani delayed litigation by taking the fight outside Pennsylvania after influencing West Virginia’s Mountaineer Racetrack and Casino lawyers to stage it at The Harv.

Paul was a month shy of turning 37 and would revisit the ring following his second-longest layoff.

Yet mentally, physically, and spiritually, he felt every bit of a man reborn.

The comeback after recovery

Humberto “Bam Baby” Toledo (41-8-2, 25 knockouts) replaced Wilfredo Negron a week before the bout. The Ecuadorian held the WBC Latino Super Featherweight and Fecarbox lightweight titles. He was a step up in status.

To Paul, he was another journeyman who would get trounced.

But even Tom Yankello was astounded at how assertively Paul would do it that evening. He evaded punches, landed his jab at will, and appeared to enjoy himself. This was especially evident in the second round when Paul bludgeoned Toledo with a right that sent his mouthpiece sailing into the third row. “Paul was rejuvenated,” Tom Yankello said. “He was on his game like he had never left. I just believed he could win a world title again.”

Mentally, physically, and spiritually, Paul felt every bit of a man reborn.

The TNT team would settle for a vigorous eight-round unanimous decision before an energetic audience that included Crystal Connor, Nadine, and a new girl Paul had been dating during his stint at Transitions. “I felt really good,” Paul said. “(Toledo) got a good beating. I had been clean for a really long time and could’ve fought anyone.”

McCauley continued pursuing his own fight by filing a lawsuit to save their old contract, but Horn shoved back and swayed McCauley and Acri into dropping their claims that fall. Though contentious and unpleasant, the victory was more significant to Paul than the one he earned against Toledo. It enabled him to concentrate on boxing and nothing more.

The lion’s share of Paul’s take from the Toledo gate – estimated to be in the tens of thousands – covered unpaid billing statements and debts owed to previous landlords. The rest financed Paul’s food and rent at a two-story brick house owned by Tom Yankello across the street from his gym. The living and training arrangement ensured stability, a non-negotiable prerequisite for Paul’s return to prominence.

And with TNT, he was well on his way. Paul had climbed to number 11 among WBA junior welterweights before battling Solomon Egberime on December 1 at The Harv.

Egberime (22-3-1, 11 knockouts) was an ex-Olympian from Nigeria and erstwhile Australian and Oriental super lightweight champion making his American debut. He was also fourteenth in the WBO, making him Paul’s highest-ranked rival since Dorin.

Nonetheless, Paul likened himself to a man who had risen from the dead. He stepped into the ring wearing a black robe with “A Phoenix Rising” imprinted across its back. The words symbolized his road to redemption and revealed he was a changed person. He wore his hair twisted into cornrows for the occasion and even looked different.

His counterpunching prowess was still recognizable, though Egberime would make him earn every inch.

Paul measured Egberime with lukewarm jabs through the first two rounds. Egberime threw a hard right to Paul’s chin in the third, but Paul caught him with a left and several combos in the fourth. Egerberime answered aggressively in the fifth and the sixth and returned to his corner each time sucking wind. He was gutsy, but Paul was in better condition and defensively superior.

Egberime wounded Paul’s right eye with a headbutt in the ninth, but Paul avenged it with a clean two-punch combo to Egberime’s face in the tenth.

Both boxers stared each other down after the final bell, chest-to-chest, before peeling away to await the judges’ scores. Paul led the punch count and controlled most of the rounds, so he was unmoved when it was announced that he had taken another unanimous decision. “Good fighter,” Paul said of Egberime. “Angles, positioning… I made it where the only person he’d be able to hurt was himself, and it was a boring-ass Paul Spadafora fight.”

It was also a Spadafora victory that would extend his record to 47-0-1 and place him at number eight in the IBF.

via wms702 on YouTube:

TNT quickly entered negotiations in January of 2013 to get Paul in the ring against a rising star named Vernon Paris, whose only loss came by a ninth-round technical knockout to [former welterweight champion Zab] Judah. A strong performance over Paris could plant Paul into discussions as a worthy challenger for WBC lightweight champion Adrien Broner or WBA welterweight champion Paulie Malignaggi.

While awaiting word, Paul joined Horn at his summer home in Bergen, New Jersey. He ran the boardwalk and trained with strength-and-conditioning coach Dave Paladino. Under the terms of his TNT contract, Paul also collaborated with Horn to reform his image through speaking engagements warning children about making wise choices in the presence of drugs and alcohol.

Upon discovering talks to fight Paris had disintegrated, Paul returned to [veteran boxing coach Andrew “Buzz”] Garnic’s wooded compound [in the secluded hills of Coal Center, Pennsylvania] that March to prepare for Paris’s replacement – a scrappy gatekeeper named Rob Frankel.

At 32-12-1 with six knockouts, a Frankel fight initially seemed like a lateral move. He was Adrien Broner’s sparring partner, and Paul would have obviously preferred signing to box Broner. But the April 6 bout would mark Paul’s third in eight months, and the victor would at least attain the vacant NABF super lightweight belt. “I always thought to compete for a NABF title, you have to be a good fighter,” Paul said. “(Frankel) didn’t seem like someone who should be fighting for this.”

Paul reinforced this assertion against Frankel early and often. After getting popped with a jab to the nose in the first round, Paul opened a cut below Frankel’s right eye with a searing left in the second.

Following a conservatively-paced third, Paul unlocked his arsenal by spreading jabs, hooks, and uppercuts to Frankel’s head and body. He opened a considerable gash above Frankel’s left eye in the sixth. The blood distorted Frankel’s vision, enabling Paul to wail away with consistent rights.

By the end of round 10, Frankel’s mug resembled a slaughterhouse floor, and Paul would obtain a messy unanimous decision. “Frankel was a rugged kid who could hurt ya, but Paul walked through him,” Horn said. “The personal trainer (Paladino) worked Paul’s legs and stamina and strength in a way that Paul had never done before, and it brought out a whole different element.”

With his new title in hand and circulating mention that Paul was only a victory shy of tying Rocky Marciano’s 49-0 undefeated streak, TNT anticipated it finally had its promotional elements lined up to lure an eminent opponent. But securing boxers of any standing proved onerous. Paul was still seen as a skilled southpaw who could make any fighter look inept. He also was no longer considered a major draw, and TNT could not offer a purse large enough to make it worthwhile.

Mark Yankello (Tom’s brother) nearly signed Paul to a bout with Puerto Rican prospect Thomas Dulorme before negotiations faltered that summer when the original proposal – a featured headliner on HBO’s Boxing After Dark – was relegated to airtime on HBO Latino, an offshoot subscription service with limited U.S. availability. “When Paul upsets the apple cart versus a guy like Dulorme in his continuance of one of the great comebacks in recent U.S. history, shouldn’t it be seen by all fans in this country?” Mark Yankello asked the Pittsburgh City Paper, adding that the altered contract would have netted Paul “less money than he can make putting on a sparring exhibition.”

Paul was only a victory shy of tying Rocky Marciano’s 49-0 undefeated streak.

With retirement looming, Paul sought paydays that could set him up in perpetuity. Following numerous conversations with Golden Boy matchmaker Roberto Diaz, Mark Yankello was finally presented with a premier opportunity. “(Diaz) had this Venezuelan kid named Johan Perez who was a (former) WBA champion, but said they didn’t have a market for him in the U.S.,” he explained. “So Diaz told me if you want to put on an event and pay for it, he would take Spadafora on (with Golden Boy). The contract was fully executed, but the mechanism for a four-fight term was predicated upon a Spadafora victory over Perez.”

Paul needed no further explanation and agreed to challenge Perez (17-1-1, 12 knockouts) for the interim WBA light welterweight belt in a deal Mark Yankello said included “nice, minimum economic terms that could put Paul on Showtime Boxing” and would expose him to six-figure earnings.

Tom Yankello always liked Paul’s chances but realized there would be no cakewalk to victory. After losing the WBA belt to Pablo Caser Cano in 2012 following an accidental headbutt that severely cut Cano above his right eye, Perez rebounded to score a unanimous decision over Yoshihiro Kamegai (22-0-1, 19 knockouts at the time) and a majority decision over former IBF super featherweight champion Steve Forbes. He was the number-three ranked WBA contender and, at 5-foot-11, stood two inches taller than anyone Paul had encountered. His gangly reach enabled him to score easily from the outside, and he threw hooks with surprising power.

The matchup would be cumbersome, and Paul came into training camp for their November 30 battle at The Harv with explicit instructions. “Dorin was a short guy who wanted to fight Paul from the inside,” Tom Yankello said. “Paul also needed to be the better guy on the inside for this fight, and I knew (Paul) had a better inside-fighting game than Perez. Paul had to take the fight to him.”

Adjustments were made, and a new strategy was honed before Tom Yankello claimed Paul made a demand that became a hindrance. “Horn brings in McGirt the last two weeks, and (McGirt) is pushing Paul to box as a pure boxer,” he said. “Buddy is a great trainer, and he has a lot of knowledge, but he didn’t know Paul like I did, and he thought Paul needed to remain a pure boxer who fought from the outside. When you have two different trainers spitting two different things, all it will do is confuse a fighter.”

Paul could only work toward striking a balance the evening of the bout. Two years earlier, he was a cautionary tale living on borrowed time. But now he entered The Harv with the steely glare of a man attempting to complete the unfathomable.

The capacity crowd cheered in adoration as Paul strutted to the ring wearing black-and-gold gladiator garb. He felt ready to overtake Perez on sheer adrenaline alone.

Perez was also focused, but the event’s immensity did not appear to hit him as intensely. “I was walking in the casino earlier and saw Perez in the lobby licking an ice cream cone, just relaxing,” Horn said. “I told Bobby (Ortense) he’s either ignorant of what’s about to happen, or he’s very comfortable and is going to give Paul a very hard time tonight.”

Horn’s initial hunch seemed more likely in the first round. Paul boxed comfortably, scored with a few lefts, and efficiently avoided Perez’s offense.

Perez nailed Paul with a hard right to start the second and followed up with a solid right-left combo to Paul’s head. Paul dipped under some of Perez’s swings and connected with a few counterpunches but failed to land as many shots.

Paul’s defensive wizardry took over in the third. He absorbed a right hook but largely avoided Perez’s salvo by shifting, blocking, and dipping away. In some instances, he made Perez miss widely.

But Perez hit his stride in the fourth with consecutive blows that sliced a gaping cut above Paul’s left eye and bruised another spot below his right. He was finding his range and making contact with regularity, and Paul struggled to react.

Tom Yankello commanded Paul to move in closer and throw his fists. “You’ve gotta keep coming!” he squawked. “Quit bobbing and weaving on this guy! (Perez) ain’t got nothing!”

Paul tried to dictate the pace in the fifth but lunged with his punches and fought from a distance. Perez creamed Paul with a hard right. Paul slowly discovered he could not extend his arm without wincing. “(Paul) started having (left) elbow trouble after years of hyperextending and jamming it, and he never took care of it,” Tommy Yankello said. “It was an accumulation over time, and then he jammed it again.”

With the pain intensifying, Paul pressed on intrepidly and opened a cut below Perez’s right eye in the sixth round. But Perez knocked Paul off kilter by readjusting his stance and reapplying pressure from both inside and outside. He was also targeting the laceration above Paul’s eye with hard lefts, and the wound hemorrhaged well into the seventh despite cutman Garnic’s diligent efforts to keep it covered.

Perez continued stretching his lead in the eighth by widening the cut above Paul’s eye. Paul showed moxie in the ninth and tenth rounds but was slightly outpointed because of Perez’s nonstop jabs and unrelenting right cross.

His elbow throbbed, and his offense stalled. Still, Paul remained calm, knowing he always saved his best for last. “I thought to myself, I’m going to end up killing this young motherfucker in the later rounds,” he said.

True to form, Paul connected with body shots and squirmed away from Perez’s punches to take the eleventh. “Buzzy told me, ‘If you win the twelfth, you win the fight,’” Paul said. “I thought I could slide it in.”

And he usually could. But Paul’s outlook turned dire when Perez landed several lefts and rights to ensure an even more debatable outcome.

The bout stipulations permitted TNT to appoint two of the three mandated judges, and Mark Yankello had hand-picked West Virginia’s Rex Agin and James Tia. As Gianna, Giovanna, and Geno meandered through the post-fight horde with pointer fingers hoisted proudly in support of their dad, Paul prayed his hometown advantage would pull him through.

Seconds later, his breathing stiffened as he watched his adversary jump onto the ring post in jubilation when it was announced that Agin had scored the bout 117-111 and Tia 115-113, and the third visiting judge, Glen Feldman of Connecticut, ruled it a draw, giving Perez the split majority decision.

via World Class Boxing Channel on YouTube:

Paul sullenly trekked back to his dressing room. “What I did poorly was not throw enough punches,” he said matter-of-factly. “I should have been on him more. I should have been busier. I should have let my hands go.”

Tommy Yankello spun Paul’s first defeat as an advantage in front of TV cameras a few feet away. “A lot of times in the past, people avoided him because, basically, there was nothing to win and everything to lose. Now, maybe these guys will think a little less of him, and he will get even more opportunities because they’ll think they could beat him.”

Paul was too shaken to think that far ahead. He had failed his objective and, without the WBA belt, became convinced there was nothing else.

“I started drinking and drinking and drinking, and that led to more drinking, and the drinking led back to drugs, and it just never stopped,” he said. “After that title fight, there was no more Paul the boxer. There was only Paul the demon.”

Sin City Salvation

Paul Spadafora remembers the gamut of emotions, the dizzying highs and lows, the triumphs and gut-wrenching tragedies. They visit him in daydreams and haunt him regularly in nightmares.

He does his best to suppress the memories and focus on the present. Amidst the rhythmic rat-a-tat of speed bags, swooshing of jump ropes, and the violent symphony of jabs, body shots, and haymakers being exchanged within the walls of the DLX Boxing Gym in Las Vegas, Paul can be heard barking commands at his son, Geno, a sinewy 18-year-old amateur bantamweight who flaunts his dad’s shifty movement and same sneaky uppercut.

“I want to get him as many fights as we can for two years and turn him pro,” Paul says. “If he does the right thing, you never know how far he could go.”

Geno knows he should listen because very few have made it as far as his old man.

Paul gave Pittsburgh its first boxing title in more than 50 years after defeating Israel “Pito” Cardona to capture the International Boxing Federation (IBF) lightweight belt in 1999. He was commonly called “The Pittsburgh Kid,” a tag owned initially by the late Charles “P.K.” Pecora (his first trainer) and Billy Conn, the acclaimed light heavyweight champ from the city’s East Liberty section who once galvanized the nation by nearly upsetting a seemingly immortal adversary named Joe Louis.

Paul and Geno. (Photo by Nadine Spadafora)

In Paul, locals wondered whether they were witnessing Conn’s second coming. Sportswriters lauded his meteoric rise, and his management team even dubbed him Pittsburgh’s fourth franchise behind the Steelers, Pirates, and Penguins. “Paul represented a renaissance in (Pittsburgh) boxing – a rebirth of the tough, working-class fight town Pittsburgh originally was between the 1920s and 1950s,” explained boxing historian Douglas Cavanaugh. “With Paul, it was like ‘Oh my God, boxing is back!’ and everyone was ready for it.”

The excitement generated inside the ring was rarely instantaneous. Paul was never revered for his knockout power but dominated fights as a slick defensive southpaw conditioned to win 12-round marathons. He relied on guile, deceptive quickness, and a prodigious counterpunch, which, according to trainer Tom Yankello, was almost rooted in superhuman telepathy.

“(Paul) always seemed to be a move ahead of his opponents,” he told Sports Illustrated. “Larry Bird always had an instinct to know where the basketball was coming off the backboard. Paul was like that as a boxer – always in the right position.”

This sixth sense kept him from getting hurt.

“Nobody could hit Paul,” said Jesse Reid, another trainer who helped coach him through his eight title defenses. “He’s a special boxer who is up there with the best of them. He always brought an extra dimension.”

Read “Best I Trained: Jesse Reid”

Paul approached the sweet science with the fevered intensity of a mad scientist, and the gym was his fistic laboratory. He spent entire days sparring with multiple partners and long nights breaking down video footage to prepare for his next bout. Boxing brought out his best qualities. It defined his purpose and made him feel whole.

And when keeping him occupied, it quelled demons that would otherwise make his reality a living hell.

As detailed in the media for more than two decades, Paul’s debilitating addictions between fights contributed to a criminal rap sheet that rivaled his résumé of accomplishments. He was a tortured soul, a veritable Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. His narrative was one of brilliance, crippled by madness, a dichotomy of in-ring savant and out-of-ring calamity.

Alcohol was the catalyst for every bad experience, and in its wake laid a trail of pain and incarceration. It was the reason the police inadvertently shot him.

It was the reason he accidentally put a bullet through the woman he loved.

The liquor led Paul to use hardcore drugs. Nothing was off limits, especially during the several occasions he attempted to kill himself.

“If Paul would have had five years of an honest life, he would have been one of the top fighters to ever live,” lamented Paul’s older brother, Harry Spadafora. “God’s plan for Paul was different than Paul’s plan for Paul.”

Paul falls into a wistful trance when reminiscing about his July 2014 unanimous decision over Hector Velazquez. The victory capped off a sterling career but left him feeling unsatisfied.

Despite his long reign at the top, Paul remains tormented by the realization he never reached his fullest potential. When left alone, his thoughts turn dark and compel him to seek solace in the bottle.

“It (sobriety) is terribly hard… so hard,” he says. “I constantly have the devil sitting on my shoulder telling me to blow everything off and to go have another drink.”

Paul’s flesh illustrates his personal history. Tattoos covering his biceps, torso, neck, and back display a mosaic of crime, family, drug abuse, fame, fortune, and heartbreak. His right forearm displays images of his children. His opposing limb showcases sketches of a crack pipe, an ecstasy pill, and a heroin needle and stamp bag, all encircling the word “Truth.” In recent years, Paul extended the canvas to include “PK” (Pittsburgh Kid) and “G$” (Geno Spadafora) on each temple.

His most meditative ink, however, is preserved in a stack of journals he started as a child. Paul penned his thoughts as he tried to make sense of his strained connection with his father and its devastating outcome. The prose became a needed distraction during the unnerving period he lived with a pedophile. It provided clarity when he reflected on his mother’s struggle to earn a paycheck while stumbling through abusive relationships. Later, the pages would imbue him with a sense of responsibility to stay clean so he could buy her the home he felt she deserved.

“I would write to God when I was training, but then I would stop after a fight when I was drinking,” he says. “But I needed it. You need somebody, some type of thing. I would write to God and tell him I was trying to do the right thing, trying to say the right things. It made me feel something, so I kept going.”

Paul speaks with a childlike naivety that belies his hardened exterior. He cares about public perception and feels like he is misunderstood continuously. He is determined to learn from his mistakes and aspires to leave behind a legacy not defined by his vices and vulnerabilities.

He hopes his relocation to Vegas, the world’s fight capital, was a step in the right direction. “I would like to train real fighters and get them off the street,” he says proudly. “It’s going to happen – you watch!”

Reid thinks Paul is already an excellent mentor to young boxers but still expresses concern.

“A lot of people didn’t think much of Paul in the beginning, but once he started rolling (as a boxer), people started to see that he was sensational,” he says. “He had great, great skills. But when you put drugs and drinking into the mix, it just tears you up. It’s sad because you love Paul and care about him so much that you just wish you could press a button and stop it all, but it doesn’t work that way. You can try to talk to someone a million times to get them to change, but sometimes it just doesn’t happen.”

Paul realizes he must – there is no alternative. He remains upbeat in the face of cynics and is committed to fighting the good fight until the very end, just as he always did in the ring.

He leans against the ropes and nods in the affirmative while watching Geno rattle a combo against his opponent’s ribs. “I’m doing what I want to do, and I’m not going to stop doing what I want to do,” he says. “I want people to see my story, so maybe someone else doesn’t have to go through what I’ve gone through. That means I’m helping someone.”

After pondering his past, Paul laughs and points to the sky. “At the end of the day, I’m just trying to go up there,” he adds. “I’ve been stressed for as long as I can remember, dawg. I just want to get up there by doing the right thing.”