Not as Easy as it Looks

Above: Bewilderment? Awe? Maybe a little bit of sadness? Whatever you call the expression on Francis Ngannou’s face, he was clearly doubting his life choices after getting obliterated by Anthony Joshua. (Photo by Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

FRANCIS NGANNOU’S BLOWOUT LOSS TO ANTHONY JOSHUA WAS ANOTHER WAKEUP CALL FOR ANYONE WHO THINKS BOXING IS JUST ABOUT BEING A TOUGH GUY

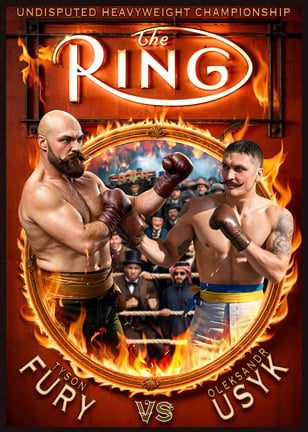

Boxing has gone through many changes in the past 120 years, but one thing remains consistent. That is, interlopers from other sports still think they can put the gloves on and compete. Fans know what will happen. We wait for it with knowing grins. Yet Francis Ngannou seemed different. In his boxing debut last October, the massive MMA star surprised viewers by going 10 rounds with Tyson Fury. Though he lost by split decision, Ngannou looked like he might be something more than a total flop. But recently in Saudi Arabia, when Anthony Joshua demolished Ngannou in the second round, it was just another case of what happens when those pesky gatecrashers intrude on our grand old sport.

Ngannou claimed he wasn’t feeling right when he entered the ring to fight AJ. He admitted on an Instagram Live session that he’d been sleepy in the dressing room and “didn’t feel completely present.”

Ngannou’s malaise was understandable. He’d been keyed-up for his boxing debut against Fury. But now, with his maiden voyage behind him, there was no such adrenaline coursing through his giant body. Moreover, he didn’t have the boxing foundation to get him through a few rounds while he tried to get his head into the game. As soon as he ended up on the seat of his pink and white trunks, Ngannou was in the same predicament as many boxing wannabes before him.

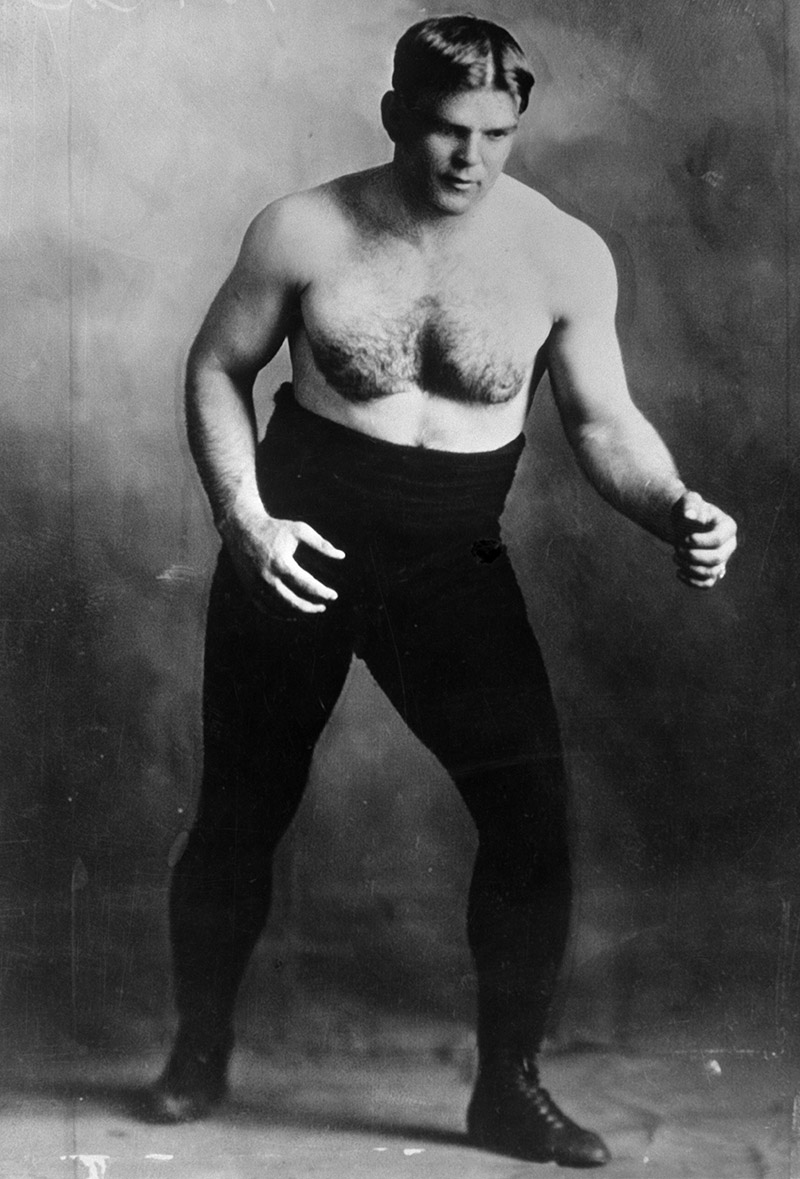

The formidable Frank Gotch, circa 1901. (Photo by The Stanley Weston Archive/Getty Images)

In 1901, wrestler Frank Gotch was in the Klondike during the final innings of the gold rush, entertaining the locals with his various holds and tosses. Frank Slavin, a 39-year-old veteran heavyweight, was also in the area on the hunt for gold. When he wasn’t panning for nuggets, Slavin had a standing engagement at the New Savoy Theater in Dawson City, knocking out the local tough guys. Though Gotch was a wrestler, he’d always wanted to be a boxer. Going by the name “Peter Kennedy,” Gotch decided to challenge creaky old Slavin.

The Yukon River setting was something Jack London might’ve conjured, replete with crusty miners peering at the action through a haze of bluish tobacco smoke. Gotch had youth on his side and was built like a dray horse. Still, he was no match for Slavin. For two rounds, the old pro hit Gotch with dozens of jabs. Sources differ on how many times Gotch was knocked down. In the third, Gotch’s frustration erupted. He grabbed Slavin and threw him to the canvas, getting himself disqualified. Years later, Gotch was still amazed at how Slavin had toyed with him. “In the space of half a minute, I had lost all thoughts of being a boxer,” Gotch said.

Gotch found great fame as a wrestler, but by 1905 he’d succumbed again to the boxing urge. After an exhibition in Buffalo where his opponent quit with a shoulder injury, Gotch arranged a fight in Spokane with a novice boxer named Boomer Weeks. It was a disaster. Gotch injured his right hand early, was dropped twice in the 10th and spent most of the bout clinching. There’d been an agreement beforehand that the bout would be declared a draw if both men were still standing at the end. Indeed, both were upright at the finish, but Gotch was as good as knocked out. Gotch’s trainer, Jerry McCarthy, remembered the event a few years later. “Weeks battered Gotch until there was not a square inch of his body not the color of a strawberry,” he said. Gotch never boxed again. His interest in pugilism had been cured.

Years later, Gotch was still amazed at how Slavin had toyed with him.

Danny Hodge had a valid amateur wrestling background that included a silver medal at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. Yet he, too, had an itch to try boxing. After 17 amateur bouts, he turned professional.

Fighting mostly in his hometown of Wichita, Kansas, Hodge compiled a 7-1 record. The state commissioner occasionally objected to Hodge’s underwhelming, handpicked opponents, which led to his being matched against Nino Valdez, a perennial heavyweight contender from Cuba. Valdez massacred Hodge in eight rounds. “Hodge bled profusely from the second round on,” reported the United Press.

Hodge immediately retired from boxing and opted for a wrestling career. He was better off. “I always felt ill at ease with a pair of boxing gloves tied on my hands,” Hodge said, “and I could never get over the urge to grab an opponent and slam him to the mat.”

Though not of the same athletic pedigree as Hodge or Gotch, another wrestler who imagined himself to be a boxer was Sterling “Dizzy” Davis. In 1959 a Texas promoter named Pat O’Dowdy decided to put the pudgy Davis in the ring with Archie Moore, the light heavyweight champion. O’Dowdy booked the fight at the Ector County Coliseum in Odessa, Texas, before an amused audience of about 1,700. The state commissioner had warned Moore ahead of the bout to “not make a fiasco of this thing.” Moore obliged, cutting Davis over both eyes and dropping him three times in the second round. The mess was stopped in the third.

Archie Moore (right) sandwiched the cakewalk against “Dizzy” Davis between two light heavyweight championship victories over Yvon Durelle. (Getty Images)

Unlike Jack Dempsey’s farcical bouts with pro wrestlers, Moore’s fight with Davis was considered an official contest and went on his record as a KO win, as did his bouts with other wrestlers, Roy Shire and Mike DiBiase. Moore must’ve enjoyed beating up wrestlers. As for Davis, losing to Moore was both his boxing debut and swansong. He did, however, have a strange personal life. In the 1970s, he served prison time for stock fraud and became a practicing psychologist after his release. He was imprisoned again after helping to finance a jailbreak involving his son.

Football players have come into boxing with nearly the frequency of grapplers. Few inspired as much media hype as Ed “Too Tall” Jones, the enormous defensive end of the Dallas Cowboys. Jones shocked the sports world when he abandoned a successful NFL career to try boxing.

Between November 1979 and January 1980, Jones rang up a 6-0 record against some dreadful opposition, including a couple of geezers with falsified records. CBS was initially interested in airing Jones’ fights, but his absence of skill plus his bland opponents made for some bad TV. Though he moved well for a 6-foot-9, 250-pound man, Jones lacked finesse in the ring. Bill Gallo of the New York Daily News said Jones threw his left jab “like he’s tossing tinsel on a Christmas tree.”

Football players have come into boxing with nearly the frequency of grapplers.

Then, only a few months into his boxing experiment, Jones announced he was returning to football. He was vague about his reasons for quitting boxing, saying only, “It just didn’t work out.” Jones’ trainer, Jimmy Glenn, once recalled for the Orlando Sentinel, “He was really serious and wanted to do it, but his coordination wasn’t there.” Other rumors included Jones’ fear that his mother might see him knocked out, and that he found boxing to be more difficult than he’d imagined. Columnist Larry Fox may have captured Jones’ mindset best. “For a man weaned on team sports,” Fox wrote, “boxing can be a lonely profession, especially when you’re not very good.”

The most repugnant example of a football player-turned-boxer would have to be former New York Jets pass rusher Mark Gastineau. With allegations of fixes arranged by his devious manager, Rick Parker, Gastineau’s 1990s ring career was dubious from the start. The talentless Gastineau eventually retired after a knockout loss to another ex-football star, Alonzo Highsmith. And Highsmith wasn’t much, either.

Highsmith, formerly of the Oilers, Cowboys and Buccaneers, had a longish ring career, going 27-1-2 (23 knockouts). His manager, Bob Spagnola, admitted to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that Highsmith was fed easy challengers because he was “green” and needed to be “protected.” Describing the quality of Highsmith’s opponents, Spagnola said, “I was digging up graves.” That tells us all we need to know about Gastineau.

Mark Gastineau (right) closed the book on his boxing phase after getting knocked out by Alonzo Highsmith. (Photo by Al Bello /Allsport)

Along with a season on the Chicago Bears in 1939-40, big Jack Torrance was a standout college athlete from LSU. He was best known as a record-setting shot putter who competed at the 1936 Olympics. Convinced that heaving an iron ball was a natural segue into boxing, the 6-foot-5, 300-pound “Baby Jack” eschewed any amateur fights and went straight into the pros.

Torrance’s bouts looked suspicious. His manager, Herb Brodie, was eventually suspended for attempting to fix a fight for Torrance in New Orleans. In April 1937, Torrance made his New York debut against an opponent who matched his own mastodon-like proportions, the enormous Abe Simon. (Ironically, Simon had been a shot putter in high school.) Torrance, now facing a legit boxer, was busted up and KO’d at 1:02 of the second round. Four months later, he was matched against 190-pound Murray Kenner in Washington. This time, Torrance lasted into the fifth, taking what the Associated Press called “a terrific beating” before being knocked cold. Soon after, Torrance joined the NFL. It was safer.

Not a football player or shot putter, Paul Anderson was known as the strongest man in the world back in the 1950s. The mammoth native of Toccoa, Georgia, set several records in weightlifting and earned a gold medal at the 1956 Olympics. Standing 5-foot-10 and weighing 300 pounds, Anderson was freakishly strong, known to pound nails with his bare fist. After a short stint in professional wrestling, he thought boxing was the obvious next step. He even hired Angelo Dundee as an advisor. By April of 1960, Anderson was set for his boxing debut in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Paul Anderson’s physical strength may have been otherworldly, but his boxing skills were weak. (Photo: Getty Images)

Anderson met a chap named Attilio Tondo, whose record was 3-7. The mountainous Anderson learned that boxing isn’t something you go into on a whim, even if you outweigh your opponent by 100 pounds. Within a round, Tondo had pounded Anderson’s left eye shut. In the third, the world’s strongest man meekly asked the referee to stop the fight. “I was completely pooped,” he said. Anderson had a few more fights of the fishy variety and then announced he was leaving the ring to focus on more altruistic pursuits. He tended to exaggerate his boxing success, claiming his record was 10-1, when it was actually 2-2.

For decades, we’ve watched wrestlers, football stars and Olympic strongmen try to box. It hasn’t been all bad. Paul Berlenbach came from an amateur wrestling background and had a tremendous boxing career in the 1920s. Charlie Powell was a revered football player with the 49ers and the Raiders, and he became a well-respected heavyweight contender of the 1950s and ‘60s. There have been others. More often than not, though, as Too Tall Jones put it, things don’t work out.

Once Conor McGregor earned millions of dollars for his loss to Floyd Mayweather in 2017, it was inevitable that more MMA stars would try their luck with the big gloves. It had already been happening to a degree, but the Mayweather-McGregor bout was a history-maker. It proved that even if an MMA fighter can’t succeed at boxing’s top level, they could make top-level money. Even with Ngannou being flattened by Joshua, there will be more MMA fighters wanting to try boxing. And the boxing world will make room for them. Mayweather and Joshua made millions by knocking off a pair of MMA guys. It’s not absurd to think Canelo Alvarez might want to do the same someday.

If you have friends who still insist that Conor McGregor’s “success” against Floyd Mayweather was because of elite-level boxing skills, de-friend them immediately. (Photo by Jeff Bottari/Zuffa LLC/Zuffa LLC via Getty Images)

Ngannou says he wants to continue boxing. Why wouldn’t he? With the $30 million he reportedly earned against Fury and Joshua, he’s the wealthiest 0-2 fighter to walk the earth. Granted, his allure has diminished, but he can be recycled. The search will be on for a lesser opponent, just to see if he can actually win one.

Still, there was something poignant in Ngannou’s loss to Joshua. The look on his face when Joshua knocked him down for the second time said it all. He was utterly deflated, as if he’d just received some sad news. The same expression probably appeared on the faces of all those who came from other sports to try boxing. It must be a sick feeling to realize you’ve wandered onto someone else’s turf, and the only way out is on your back.