Staying Undisputed: Can boxing return to the days of one champion per division?

Since the onset of the “four-belt” era (defined by the WBO’s formation in 1988) only 13 boxers have earned the title of “undisputed champion” – designated here as those who hold or have held the WBC, WBA “Super,” IBF and WBO belts simultaneously: Bernard Hopkins, Jermain Taylor, Terence Crawford, Oleksandr Usyk, Josh Taylor, Saul Alvarez, Jermell Charlo and Devin Haney among the men; Cecilia Braekhus, Jessica McCaskill, Claressa Shields (twice), Franchon Crews-Dezurn and Katie Taylor among the women. Since Crawford’s triumph over Julius Indongo in August 2017 to become the first man to own all four widely-recognized alphabet belts since Jermain Taylor turned the trick against Hopkins in July 2005, the term “undisputed” has joined winning a Ring Magazine championship belt as the epitome of boxing supremacy, a distinction that enhances the reputations and legacies of those 13 athletes while also separating them from their contemporaries. At the same time, however, this honor is more inclusive yet less subjective than topping the “pound-for-pound” list at any given time. Because of this, being known as “undisputed” represents the best of all worlds in terms of identifying who is the best of the best during a given period of time.

That seven of the 13 fighters became undisputed since August 2020 marks a welcome step toward restoring some sort of order in a sport rife with what Hall of Fame broadcaster Howard Cosell called “jurisdictional chaos.” For decades, fans, writers, fighters, broadcasters, pundits and historians have clamored for a return to a simpler era in which one athlete claims dominion over a given weight class, so much so that entities such as The Ring and the Transnational Boxing Rankings Board have sought to identify the “real” champions, and, in the case of the latter, trace their lineages as far back as possible. But while progress has been made – 17 fights involving unified or undisputed championships have been waged since February alone – “The Sweet Science” still has much work to do if it is to recapture a semblance of past glories and once again become a streamlined, easy-to-follow sport capable of attracting, and keeping, a new generation of fans.

The biggest impediment to that goal is that while it’s difficult enough to become undisputed, it’s been made impossible to remain undisputed. This is especially true among the octet of men, who have made a combined three successful defenses between them – Hopkins’ decision win over Howard Eastman in February 2005, Usyk’s eighth-round TKO of Tony Bellew in November 2018 and Josh Taylor’s split decision over Jack Catterall this past February. This situation exists in part because of two specific policies created and enforced by each of the organizations: The collectively huge bite their sanctioning fees remove from the champion’s purse and the absence of cooperation regarding mandatory challengers.

Usyk defended his undisputed cruiserweight championship once. Photo by Richard Heathcote/Getty Images)

The WBC, WBA and IBF each charge 3% of a fighter’s purse for the opportunity of fighting for their belts while the WBO’s bill stands at 2%, meaning that both champion and challenger must fork over 11% of his or her pay to secure their collective blessing. This, in effect, is a tax and while harsher critics have called it “extortion,” it does present an enormous disincentive for any fighter to remain atop the undisputed mountain once he or she reaches that summit.

While superstars like Canelo can turn over $4.84 million of the reported $44 million purse he made against Caleb Plant to the alphabet groups and still have enough left after paying his promoter, manager, trainer, the rest of his support team, sparring partners and the governments of Mexico and the United States to remain very comfortable financially, it is quite another proposition for Haney to do the same with the reported $2.8 million he made against Kambosos. Even Kambosos, whose base purse was said to have been $10 million, came away with far less than that in the end.

Another name for boxing is “prizefighting,” and under current conditions, fighters who don’t occupy Canelo’s superstar strata have to think long and hard about whether the “undisputed” label is truly worth keeping.

The other issue is that newly crowned undisputed champions are confronted with the following age-old scenario: “In order to keep your championship, you must defend it against our number-one contender within a specific time period or else be stripped.” Complying with that mandate was easy during the golden age when there was one champion and one widely accepted set of rankings, but today’s environment presents a double-whammy that makes this task unattainable: Four separate names in the top spot and the two-fight-per-year schedule observed by most of today’s champions.

For Alvarez, whose star power generates countless millions for everyone involved in his fights, allowances have been made in order for him to remain undisputed, allowances that were also granted to past megastars who didn’t share his four-belt championship status. His September 17 fight with Gennady Golovkin has received the green light by all four bodies despite the fact that GGG is unrated at 168 by any of them, and this, in turn, has forced other names in the division to wait their turn – and potentially wither on the vine. Those names include WBC “interim” champion David Benavidez and top challengers as listed by the WBC (Russia’s Pavel Silyagin, the organization’s “silver” titlist), WBA (Kazakhstan’s Aidos Yerbossynuly, the body’s “official challenger”), IBF (third-rated Russian Evgeny Shvedenko; the top two spots are vacant) and WBO (Great Britain’s Zach Parker). Except for Benavidez, the other names are obscure to even the hardest of hard-cores and it’s easy to see why the alphabet groups – and Canelo himself — agreed on the choice of Golovkin.

Canelo will defend his undisputed 168-pound championship for the first time in a trilogy bout with Gennadiy Golovkin. Photo by Ethan Miller/ Getty Images

While Haney is contractually obligated to give Kambosos a rematch for the undisputed crown, another example of this conundrum can be found with Jermell Charlo, who is the one and only champion at 154. Should he decide to stay where he is, his options are as follows: A “unification” showdown with WBC “interim” titlist Sebastian Fundora, a third fight with Tony Harrison (the WBC’s number-one challenger), Uzbekistan’s Israil Madrimov (the WBA’s top contender), Russia’s Bakhram Murtazaliev (the IBF’s number-one choice) and Australia’s Tim Tszyu (the WBO’s option). The most financially attractive opponents are Fundora and Tszyu, but if he chooses to fight either one of them next, would he still get to keep all of his belts if Harrison, Madrimov and/or Murtazaliev assert their rights to an immediate title shot, especially since it’ll take at least a year for Charlo to get to any of them if he decides to stick it out and proceed to beat Fundora and Tszyu? Other than an absurd WWE-style “fatal six-way match,” Charlo’s most likely moves are to either to engage in one or both of the big-money matches with Tszyu and Fundora or shed the belts, move up to 160, and have everyone else fight for the scraps he’ll leave behind.

This unpalatable dynamic is further illustrated by what has happened to Josh Taylor, who lost two of his four 140-pound belts without having thrown or received a single punch. The WBA stripped Taylor on May 14 for his refusal to proceed with a mandatory defense against Dominican Alberto Puello (who has been the entity’s number-one contender since July 2019) while Taylor chose to relinquish his WBC title this past week because he wanted to fight a rematch with Jack Catterall instead of top WBC challenger Jose Zepeda.

“The WBC truly regrets having lost so much time and having mandatory contender Jose Zepeda frozen as well as other fighters in the division,” the WBC said in a statement.

These issues are not nearly as pronounced in the women’s game because its roster of challengers, especially in the higher weight classes, aren’t nearly as deep. Welterweight monarch Cecilia Braekhus made 10 successful defenses of her undisputed welterweight championship between September 2014 and November 2019 while her successor McCaskill notched her third successful defense against Alma Ibarra last month. Taylor, the one and only lightweight champion since June 2019, recorded her sixth successful defense with a 10-round split decision over unified featherweight titlist Amanda Serrano in April. To its credit, the women’s game is much closer to the ideal than the men in that fighters are given the best chance to construct the kind of dominant single-division reigns that marked the sport’s various heydays.

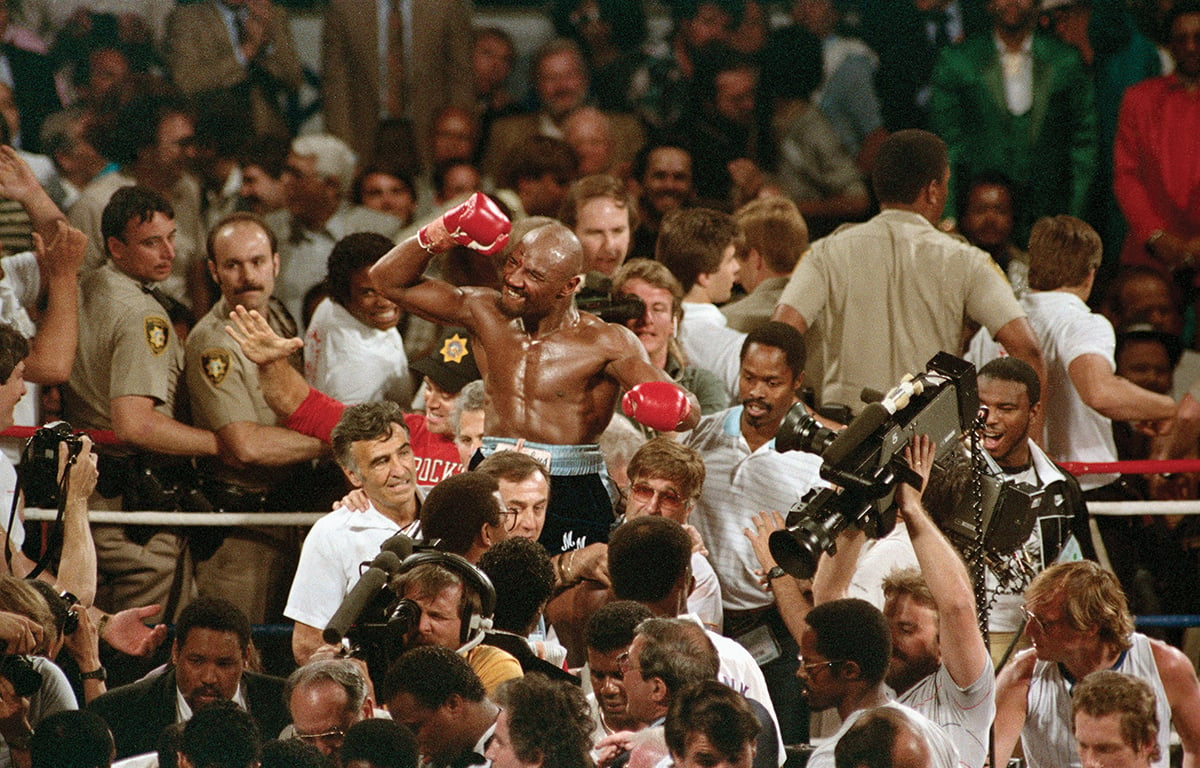

The great Hagler was considered undisputed champion at 160 for the entirety of his seven-year title reign. Photo by Ring archive / Getty Images

The following suggested solutions for these issues are simple to write but difficult to execute because enacting them would require a seismic shift in terms of the ultimate objective; prioritizing the greater good of the sport over the desire to generate maximum profit in the here and now. That would be a heavy lift – if not a hopeless one — given boxing’s “red light district of sports” reputation, but it doesn’t hurt to at least put forth these ideas. In other words: Nothing ventured, nothing gained. So here goes:

*The first step would be for Mauricio Sulaiman (WBC), Gilberto Mendoza Jr. (WBA), Daryl Peoples (IBF) and Francisco “Paco” Valcarcel (WBO) to decree that their organizations would be willing to accept a smaller slice of the pie for undisputed championship fights in order to lessen the financial pinch on the fighters and to make the defending champion’s decision to remain at the top of the mountain a more attractive one than dropping the belts solely for money reasons. This gesture not only would give the organizations a rare dose of positive public relations, it also would lend credibility to their public statements that they are supportive of the athletes and their well-being, financial and otherwise. After all, a potential string of successful undisputed title defenses would bring those fighters much more income in the long term than being forced to surrender their hard-earned status for reasons other than being vanquished inside the ring.

*The second step would be for all four ratings committees to agree on a single number-one challenger for the undisputed champion to face. Unlike the first suggestion – which would require a collective transformation on several levels to occur – this step should be easier to complete. One attractive way to achieve this end is for the sanctioning bodies to stage a series “number-one contender tournaments” in each weight class – say the WBA’s designee versus the WBC’s choice and the IBF’s pick against the WBO’s, and have the winners meet to become the universally recognized top contender for the undisputed champ.

*The final step would be for the organizations to mandate that the undisputed champion defend his or her titles a minimum of three times per year – including at least once against the universally recognized mandatory challenger — while also encouraging others in the top 10 to face one another to make their cases of being the next person in line. This should somewhat ease the logjam that currently exists, and that glut could be further unclogged if these “contenders’ matches” feature a financial bonus for those who choose to engage in them instead of sitting back and waiting for others to lose.

Of course, the ideal would be to have the sport administered by an overarching entity that features one set of ratings, frequent championship fights involving worthy challengers and a single monarch ruling over every division. Unfortunately, the current structure is nowhere near that ideal and it’s extremely unlikely that this dream scenario will happen anytime soon. Because of this hard reality, the best that can be done for now is to improve upon the structure that already exists and hope that a new set of forward-thinking leaders will emerge and serve as a catalyst for genuine change.

If boxing is to complete the journey back to its “one champion per division” roots, there must be a spark of inspiration, and, in this most cash-oriented sport, the most likely way that will occur is if the powers-that-be are convinced that a new system will result in enhanced income. The good news is that this has already happened for Division I college football, which has resolved its longstanding problem of crowning an inarguable national champion.

In years gone by, a “mythical” champion was determined by a consensus of sports writers and polling organizations, but when that process became too messy – the 1990 and 1991 seasons produced co-national champions who didn’t have any avenue for a final head-to-head showdown — a succession of systems that hoped to produce clarity were created: The “Bowl Coalition” between 1992-94, the “Bowl Alliance” between 1995-1997, the “Bowl Championship Series” between 1998-2013 and finally the College Football Playoff, a two-tiered, four-team on-field tournament that has given the sport an undisputed national champion every year since 2014. The CFP has been a success on every level; it has delivered excellent ratings (between 19 and 34 million viewers), terrific head-to-head encounters, comprehensive fan satisfaction, a sense of finality and closure, and tons of money for those who had prospered under the previous systems, especially since the sport still boasts 44 bowl games.

Boxing has long been the most compelling of sports and the proof is that so many of the other games have used the terminology and the mythology of “The Sweet Science” to elevate themselves. If boxing is to make itself the undisputed best it can be, then it should emulate the path followed by college football and create a system by which it can regain what it had lost so many years ago – an undisputed champion in every weight class reigning in an environment that has as few administrative shackles as possible.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 21 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2006. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. as well as a panelist on “In This Corner: The Podcast” on FITE.TV. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook and Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).