Larry Holmes vs. Ken Norton: Trial by Firefight

By Jerry Izenberg

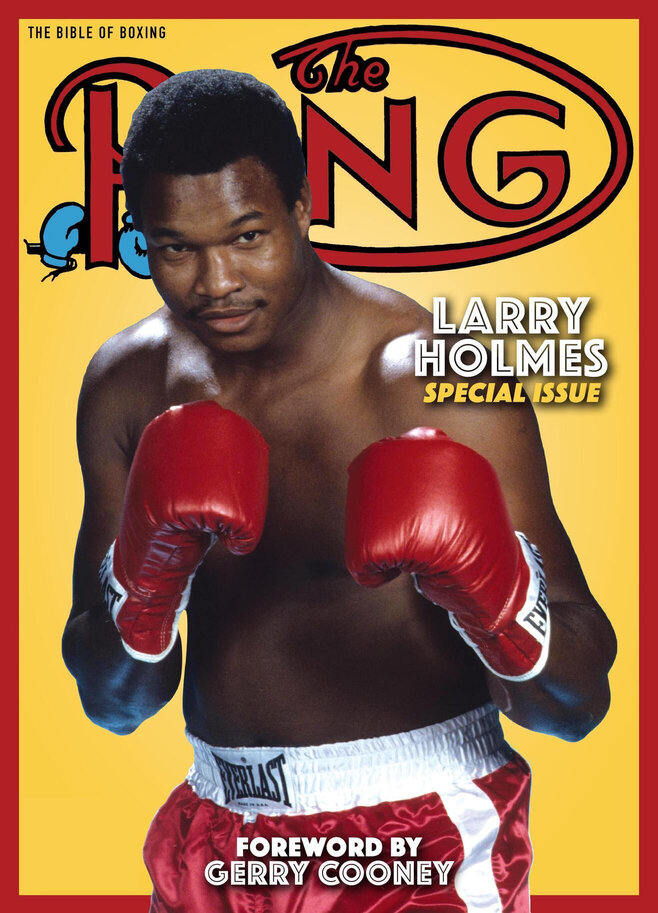

This feature originally appeared in our Larry Holmes Special Issue, which is available for purchase at The Ring Shop.

NOT EVEN AN INJURED ARM WOULD PREVENT HOLMES FROM SEIZING HIS DESTINY – AND THE WBC TITLE – DURING AN EPIC SHOWDOWN WITH KEN NORTON

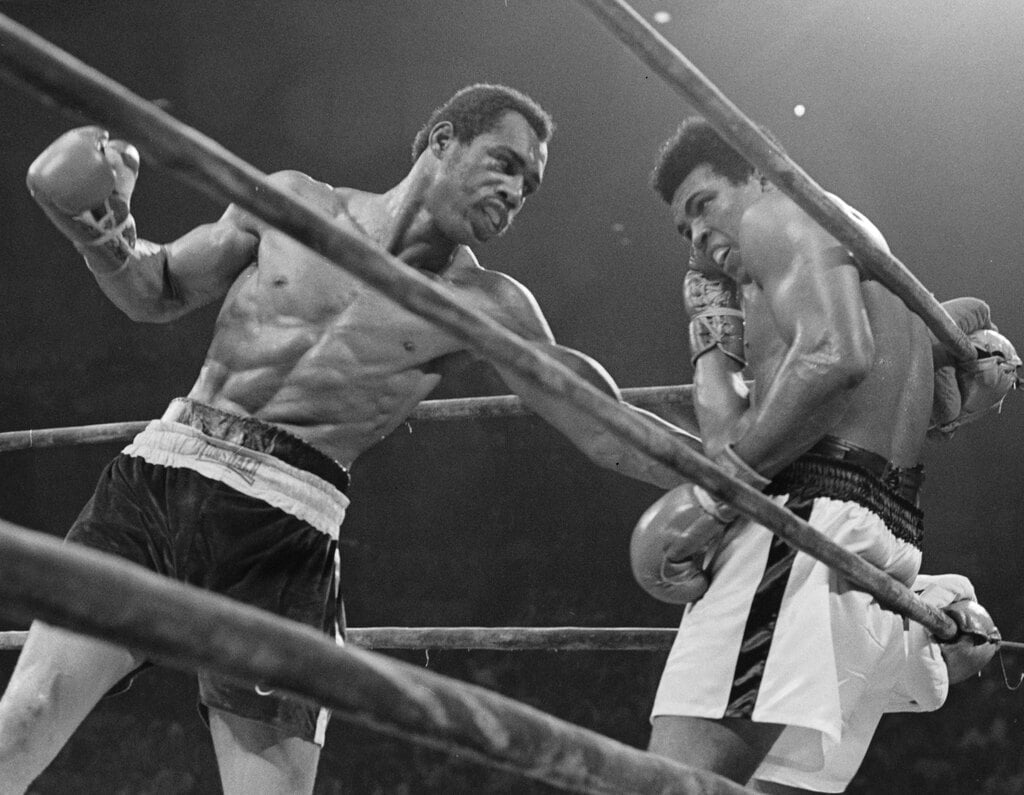

Ken Norton’s first shot at the heavyweight championship didn’t even last two full rounds. George Foreman demolished him. Nobody remembered it. The question Norton was asked the most back then was, “Aren’t you the guy who broke Ali’s jaw after he lost to Joe Frazier?”

And Larry Holmes?

In 1977, he was in Las Vegas seeking an identity against another barely-known named Ibar “The Sailor” Arrington. Holmes and I were standing in the casino at Caesars Palace when a matronly looking woman approached us. She had noticed his 6-3 height.

“Oh,” she said, “what team do you play for? I’d love to buy tickets for my husband. He loves basketball.”

Holmes turned to me and said, “I’m 25-0. What the hell I got to do for people to know who I am?”

Holmes and Norton were twin travelers down a hard-luck highway, shadowboxing to the accompaniment of a lonely blues fugue. Neither of them realized that they were headed toward an accidental collision course that would produce one of the greatest heavyweight fights in history.

Ken Norton (left) hits Muhammad Ali with a left to the body during the second fight of their classic trilogy, which took place at the Forum on Sept. 10, 1973 in Inglewood, Calif. (Photo by: The Ring Magazine/Getty Images)

It was a fight that wasn’t supposed to happen. First, Norton won a WBC-mandated box-off over Jimmy Young. Since Muhammad Ali had agreed to fight the winner after he disposed of Leon Spinks, Norton was handed a diploma that read “WBC champion.” All he had to do was watch television until Ali won. But Ali lost, and that night when Spinks was asked if he would fight Norton, he said:

“Talk to my lawyer.”

That’s boxing for “Blow a rematch and leave all that money on the table? Are you out of your freaking mind?”

So, the WBC had a champion by diploma but nobody for him to fight. In retaliation, it stripped Spinks of his title, officially named Norton as world titleholder and ordered him to face Holmes, the No. 1 contender. Las Vegas would be the site.

Holmes and Norton were twin travelers down a hard-luck highway … they were headed toward a collision course that would produce one of the greatest heavyweight fights in history.

But as soon as the fighters arrived in Gomorrah-by-the-Desert, the whole damned thing teetered on the edge of disaster.

On fight day minus six, Holmes was sparring as usual with Louis Rodriguez in the airless Sports Pavilion at Caesars. The public wasn’t there. It was as much ritual as it was preparation. He had already begun to peak and there were surely no mysteries in Louis Rodriguez for him. Collectively they had traded perhaps 10,000 punches since Larry Holmes became a pro.

Holmes released a left jab and caught an elbow directly on the biceps. And then there was this spear inside the muscle and it was burrowing deeper and deeper until he felt the pain from his eyebrows down to his ankles.

They got him the hell off the floor with as little fuss as possible. But nobody had to tell Larry Holmes it was bad … not Richie Giachetti, the trainer, who had been through so much with him – the hunger, the frustration, the depression – and not Freddie Brown, the old boxing veteran who was hired as an assistant trainer and cut man for this fight.

And, certainly, not even Rodriguez, who died a little within himself with the thought of what it might mean.

The biceps was torn.

In that instant, there was no reason to believe this fight would ever happen. They summoned Caesars house physician Dr. Joe Fink, who took one look and sent them straight down to Desert Springs Hospital to Keith Kleven, who for decades was by far the best physical therapist in town. Getting Holmes out of the hotel to the hospital and back without being seen was mandatory. Each of them knew the fight was in serious jeopardy.

When I arrived, two days later, I couldn’t find Holmes … not then … not Wednesday. He held a very brief press conference on Thursday morning but hadn’t trained for five days. When a man fighting for the heavyweight championship lays off any work at all for the better part of a week, you do not have to be too smart to know something is wrong.

When I arrived, two days later, I couldn’t find Holmes … not then … not Wednesday. He held a very brief press conference on Thursday morning but hadn’t trained for five days. When a man fighting for the heavyweight championship lays off any work at all for the better part of a week, you do not have to be too smart to know something is wrong.

We sat in his suite that afternoon and Giachetti tactfully said to his fighter, “Don’t tell him crap, Larry.”

“You want me to leave?” I asked Holmes.

“No, I want him to leave.”

I had known Larry since he had been a kid sparring partner for Ali. I was there the day he got a black eye and when advised to put a raw steak on it, he refused. “I want everyone to know,” he said back then, “who it was who gave me my black eye.”

After Giachetti walked out, Larry told me that his left arm felt dead and explained how it happened. So now I knew what it was, but in a situation like that, Larry Holmes deserved to handle his own options. I decided that some stories deserve not to be written just for the sake of a headline. I agreed I’d wait until after the fight.

Meanwhile, Kleven knew exactly what was wrong and how to handle it. When he wasn’t treating Larry with what he called high galvanic stimulation (electricity to you), he was locked in a nonstop debate with Giachetti.

“The fight is on,” Giachetti thundered.

“Not until I say it is,” Kleven shot back.

“I’m his trainer and I say it is.”

“He’s my patient and I will tell you when it’s on.”

In the end, it really didn’t matter. Larry knew he was going to fight. He asked Keith to be in the corner. Keith told him:

“Look, you can fight. … But you can’t take a hit on the biceps or you are done. I can’t help you if that happens.”

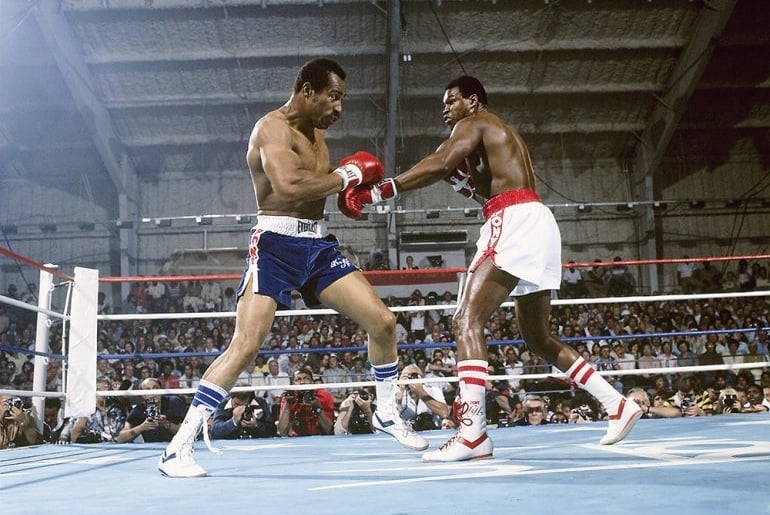

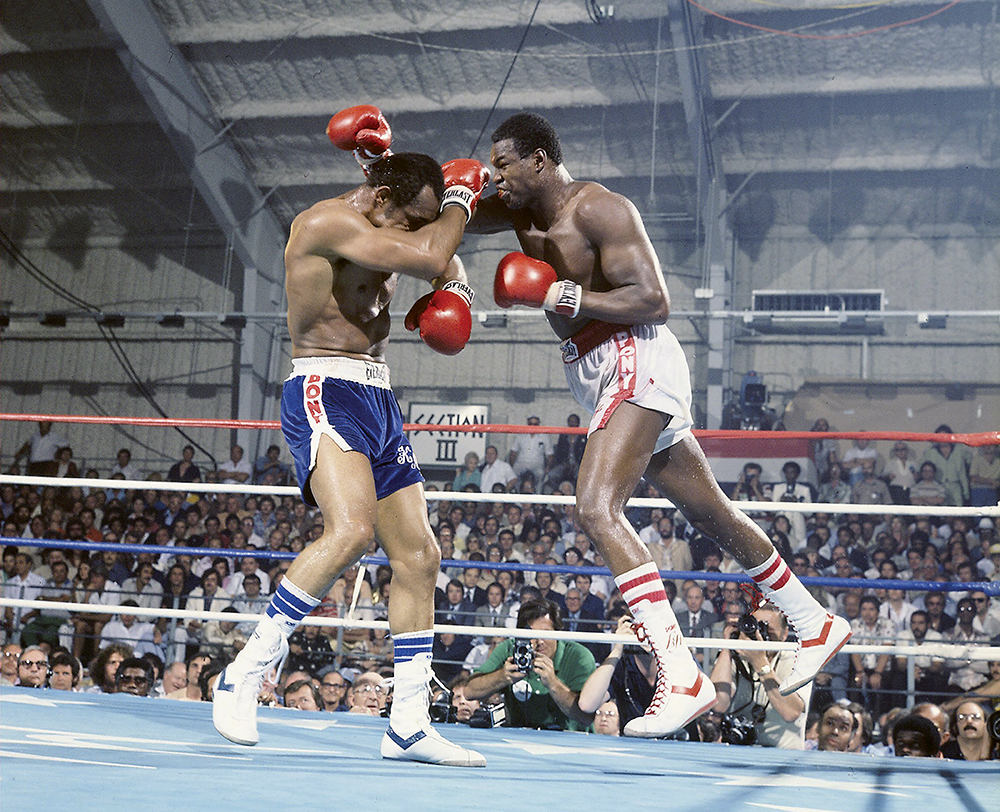

(Photo by Tony Triolo/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

But the fight went on as scheduled. The Holmes camp was hungry and desperate and saw no other options. For the full 15 rounds, their fighter performed. Norton couldn’t take advantage of him from the start because he didn’t even know about the injury. And what they gave us was a close second to Ali-Frazier III. Believe me, because I saw both live.

It began as a boxing clinic with Professor Holmes in charge … rat-tat-tat went the nonstop jab and BOOM went the uppercut or hook behind it. Despite the injury, Larry still had his left hand and, by his own admission, the jab and the hook carried him for six full rounds. But somewhere in the next two rounds, Kenny caught the biceps with a glancing blow. There wasn’t enough electricity in nearby Hoover Dam to deflect the kind of pain Holmes felt.

Norton immediately took command of the fight. He wiped out most of that six-round deficit with a combination of right and left hands that took the steam out of Holmes. But “most’’ is the operative word here. As a result, this nonstop battle raged all the way through the 14th.

There are very few tableaus in this strange business that equal what I saw before the start of Round 15. In one corner, Eddie “Bossman” Jones, Ken Norton’s second, had an ice bag glued to the fighter’s left eye, and kneeling in the ring was Bill Slayton, the trainer, pleading and urging and reminding the fighter of something he already knew all too well. It was, in truth, now or never.

Across the ring, Richie Giachetti, Slayton’s counterpart, was down in front of Larry Holmes and he was telling him he could have it all if he wanted it. He could put an end to the frustration and the big paydays that eluded them and the agonizing months of inactivity.

But now they were here and the answer was waiting across the ring and Giachetti kept reminding him about it. Then Freddie Brown, a dean of trainers himself but a second that night, leaned in and threw a ton of water over Larry and hollered at him: “Stay loose . . . Stay loose.”

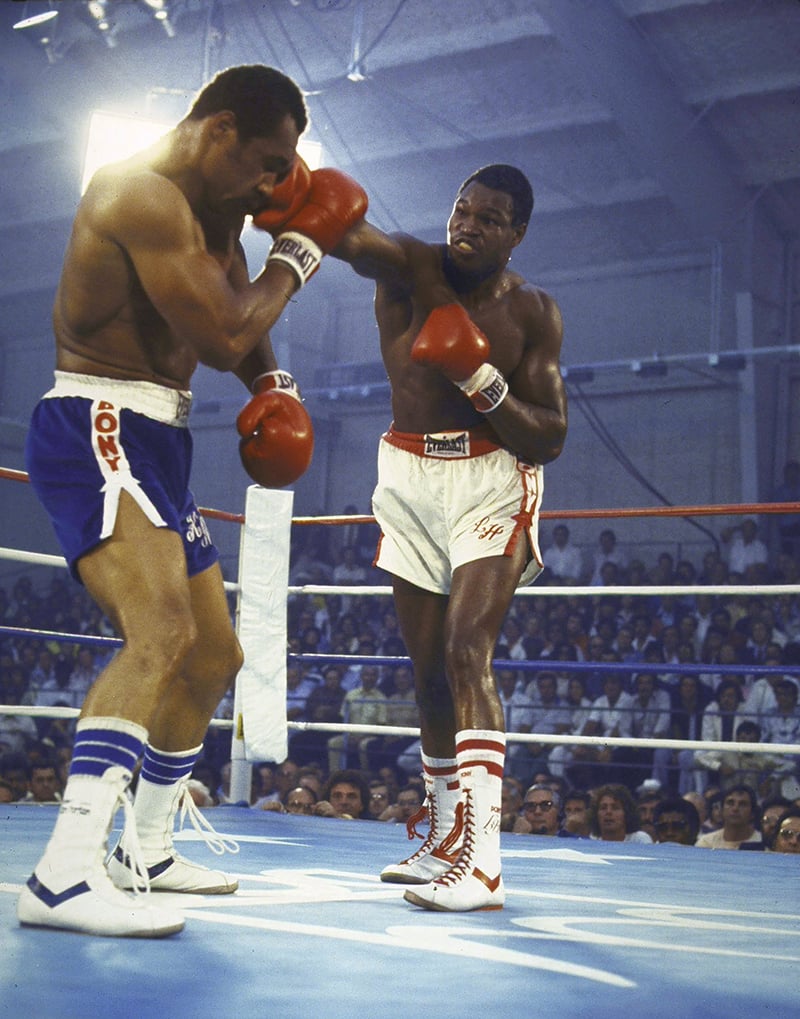

UNITED STATES – JUNE 09: Boxing: WBC Heavyweight Title, Larry Holmes (white) in action vs Ken Norton Sr, (blue) at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, NV 6/9/1978 (Photo by Tony Triolo/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images) (SetNumber: X22436)

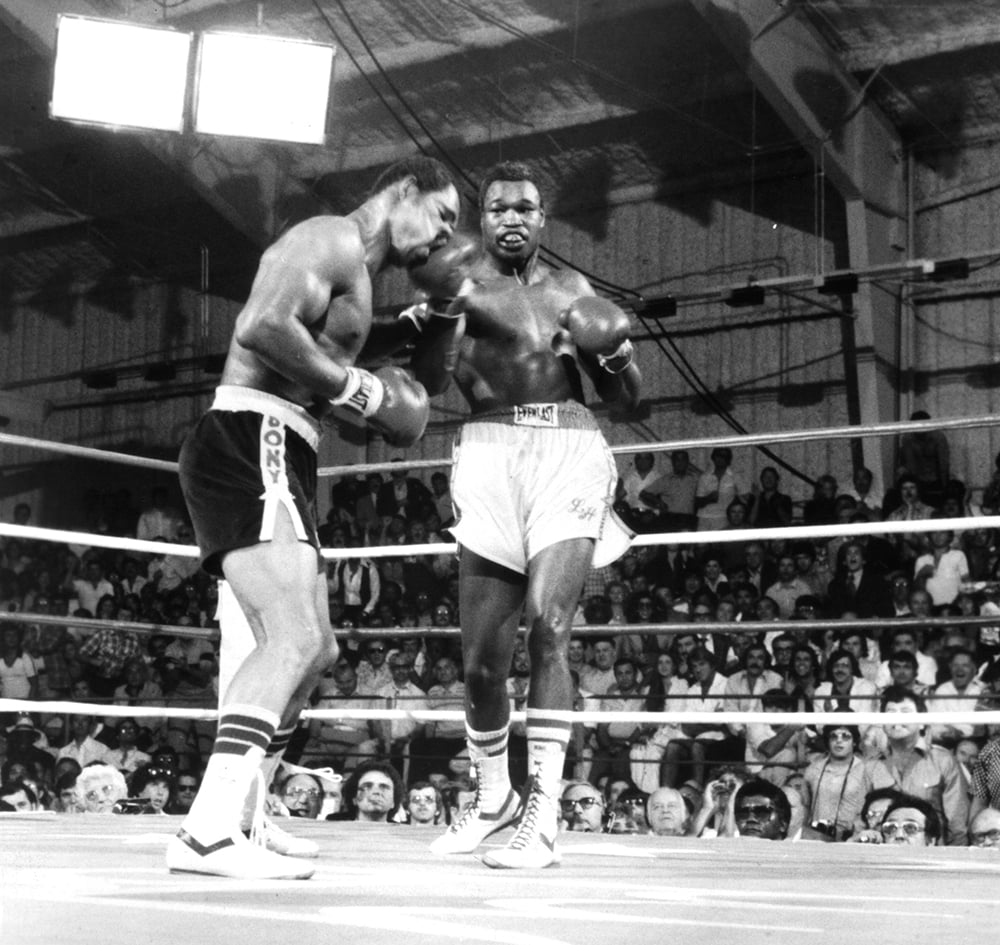

At the bell, the two of them were walking on rubbery legs, each guy trying desperately to bluff the other into thinking he had not lost his store of both cool and latent power. Actually, both had neither. They had reached the point where for them the night had become an all-out struggle for survival with what tools the blazing television lights had left them.

Now you can see this fight a lot of ways, and the way I saw it, it was dead even going into the 15th round. So here came Norton, with the water pouring off his head and the strange cross-handed guard of his, sliding forward and Holmes feinted the jab that went nowhere. Norton came over the top with a straight right hand and followed with a left hook and a straight right to the head. Holmes’ mouth was awash with blood for the second time in this fight. For an instant, his legs wobbled and his eyes seemed to glaze.

It looked very much like it might be over. With each punch Kenny threw, he nearly collapsed. With each punch Larry caught, he nearly collapsed. Norton was banging out the last chorus of what seemed to be a slow, painful dirge.

But then, just when he seemed ready to end it, his firepower was gone and his breathing was labored.

Holmes was still struggling for balance, swaying agonizingly, aching legs quivering, feet flat and wobbly. In desperation, he made a decision that won the fight. Well, not quite a decision. It was more like a drowning man clawing his way toward a bobbing life preserver.

“I thought, ‘The hell with it. I didn’t come here to lose. To hell with my biceps. To hell with the pain. To hell with all the medical advice.’”

Holmes went for broke.

In that instant, he caught Kenneth squarely on the chin. Norton stopped. He stumbled. Holmes was all over him. Left hand or right hand, it no longer made a difference. He threw the fight’s final 14 punches and landed 13 of them.

In his entire career it might have been the most ferocious one-and-a-half minutes Holmes ever put together.

Norton had so little left in his arsenal, it froze him.

Holmes made Norton pay for all the bad luck that had been his since he left school in Easton, Pennsylvania, to help support his mom and siblings with whatever he earned at the car wash. He was too tired to put him away and Norton was too proud to fall. But that last assault put Norton in a place from which there was no return.

Holmes won by a point on two judges’ cards. He lost it by a point on the third and thus earned a split decision and the title. Then he left the arena and disappeared. The rumor was he was on his way to the hospital. The truth was that he had run out of the building and jumped into the hotel swimming pool in triumph alongside Giachetti.

Strange things often happen to young fighters after they win their first big one. They become better because of the special circumstances around that victory. It happened to Muhammad Ali when he looked across the ring at Sonny Liston refusing to leave his stool after the bell rang.

For Holmes, there was a similar epiphany. It was as though he had looked in the mirror and said, “My, oh, my. Look what I did, and wait until you see the second act.”

He was right.

He became a great champion.

As for Norton, he fought on. But after falling short three times when belts were on the line (including a bitter controversial loss to Ali two-and-a-half years before losing to Holmes) and because of the way he ultimately acquired the WBC title, boxing history did not treat him as well as he truly deserved. Instead, he became the answer to a stunning trivia question:

Who was the only heavyweight champion who never won a heavyweight title fight?

YOU MAY HAVE MISSED

Read “Larry Holmes: ‘After Ken Norton, my 20 title defenses were playground stuff'” by Tom Gray

Read “A Tribute to Ken Norton” by Lee Groves