A tribute to Ken Norton

When onetime WBC heavyweight champion Ken Norton was asked how he’d like to be remembered in the 1989 video “Champions Forever,” he replied with typical thoughtfulness: “An intelligent being. A caring being. An individual when, even though he was very competitive, in his heart he never wanted to injure anyone. And that he was a man that believed in God.”

On Wednesday Norton’s once magnificent body finally succumbed to congestive heart failure at a care facility in the Las Vegas suburb of Henderson, Nevada. It was the last in a long series of physical challenges that were forced upon Norton over the past 27 years. In 1986, a near-fatal car accident broke his jaw, ribs and legs, fractured his skull, wiped out portions of his memory and inflicted a brain injury that permanently slurred his speech. His doctors told him he would never walk or talk again, but he, of course, beat the odds. In subsequent years he underwent quadruple bypass surgery, suffered a heart attack, overcame prostate cancer and survived a pair of strokes.

For those who witnessed his fighting spirit in the boxing ring Norton’s resiliency beyond the ropes wasn’t a surprise, and for those who knew him best his fortitude and positive mindset cemented what they already realized — that this was a man of uncommon character and perseverance.

During a ring career that spanned 14 years (1967-1981), Norton compiled a 42-7-1 (33) record, but more importantly he was an integral part of what most historians regard as the greatest era the heavyweight division has ever known. He was a perennial top contender in a field that included Oscar Bonavena, Ron Lyle, Jerry Quarry, Duane Bobick, Joe Bugner, Earnie Shavers and Jimmy Young among others and he gave the top dog, Muhammad Ali, everything he could want – and plenty that he didn’t want.

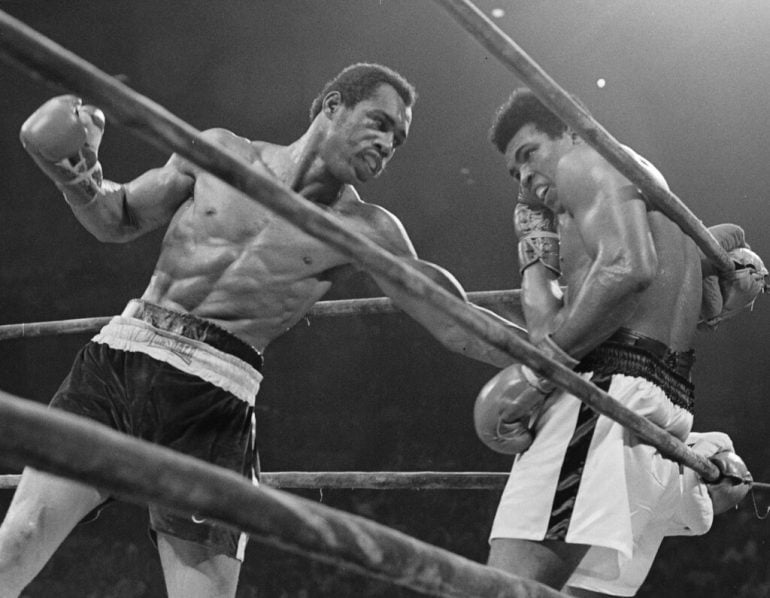

.jpg) His introduction to the boxing world at large produced shock waves worldwide, for on March 31, 1973 in San Diego’s Sports Arena, Norton not only defeated Ali by split decision, he also broke the sport’s most prolific jaw. When the clean, quarter-inch wide fracture occurred remains in dispute; Ali and chief second Angelo Dundee said it happened in round two while Norton and head trainer Eddie Futch contend it was the 11th. What wasn’t in dispute was that Ali had been soundly beaten and Frank Rustich’s 7-4-1 card best reflected what most people saw in a split decision victory that should have been unanimous.

His introduction to the boxing world at large produced shock waves worldwide, for on March 31, 1973 in San Diego’s Sports Arena, Norton not only defeated Ali by split decision, he also broke the sport’s most prolific jaw. When the clean, quarter-inch wide fracture occurred remains in dispute; Ali and chief second Angelo Dundee said it happened in round two while Norton and head trainer Eddie Futch contend it was the 11th. What wasn’t in dispute was that Ali had been soundly beaten and Frank Rustich’s 7-4-1 card best reflected what most people saw in a split decision victory that should have been unanimous.

“I cried tears of joy and was on a natural high, higher than any I’d ever felt before or since”” Norton wrote in his autobiography “Going the Distance,” which was written with Marshall Terrill and Mike Fitzgerald. “The emotions and feelings from a victory of that magnitude are hard to put into words. My jaw muscles ached the next day from smiling so much – my smile could have lit up the Las Vegas Strip and served as backup power to the Hoover Dam!”

From that point forward Norton was a force in the heavyweight division. A little less than six months later Norton and Ali met again and even though the ex-champion scaled a lithe 212 – nine pounds less than in the first fight and his lightest weight since his war with Bonavena nearly three years earlier – and showcased the constant movement that reminded many of his incandescent prime, Norton summoned a huge second-half rally that brought him to the brink of a second monumental victory. Again, the decision was split but this time Ali came away with the “W.”

Three years later, after Ali improbably regained the title from George Foreman, the pair finally fought their rubber match with the biggest prize in sports on the line. Norton appeared to do more than enough to dethrone the 34-year-old master but referee Arthur Mercante Sr. (8-6-1) and judges Barney Smith (8-7) and Harold Lederman (8-7) thought differently and enabled a weary and relieved Ali to keep the title. No heavyweight champion had lost his title by decision since Max Baer’s defeat to James J. Braddock in 1935 and the streak wouldn’t be broken until 1978 when Ali shockingly lost to Leon Spinks.

Norton bedeviled Ali so much that he often was compared to other fighters who had the number of otherwise legendary champions. Willie Meehan went 2-1-2 against Jack Dempsey while Shorty Hogue took two out of three fights from Archie Moore but while Norton achieved more than either Meehan or Hogue on the world stage his ability to short-circuit Ali remained, at least to the masses, Norton’s defining trait.

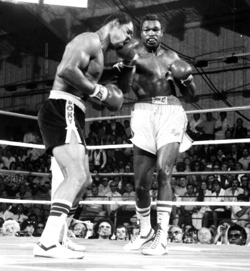

But while Norton was Ali’s stumbling block, gargantuan punchers proved to be Norton’s. A trio of monstrous heavyweight hitters laid waste to Norton as then heavyweight champion George Foreman took exactly five minutes to prevail while Earnie Shavers (118 seconds) and Gerry Cooney (54 seconds) required far less time. The Cooney fight proved to be Norton’s last inside the squared circle but, as stated at the beginning, many more battles beyond the ring would follow.

But while Norton was Ali’s stumbling block, gargantuan punchers proved to be Norton’s. A trio of monstrous heavyweight hitters laid waste to Norton as then heavyweight champion George Foreman took exactly five minutes to prevail while Earnie Shavers (118 seconds) and Gerry Cooney (54 seconds) required far less time. The Cooney fight proved to be Norton’s last inside the squared circle but, as stated at the beginning, many more battles beyond the ring would follow.

The angst of the Ali loss in Yankee Stadium ate at Norton but it didn’t stop him from eventually climbing to the heavyweight summit. His route, however, was decidedly unique.

On Nov. 5, 1977 Norton defeated Young by split decision in a 15-rounder billed as a WBC heavyweight elimination contest. Ali, then the champion, wanted to squeeze in one more optional defense against 1976 Olympic champion Leon Spinks in February before having to face Norton a fourth time. The WBC, which originally mandated that Ali had to sign to meet the Norton-Young winner by Jan. 5, 1978 or else lose his title, yielded to Ali’s will and authorized the Spinks fight on the condition that both Ali and Spinks sign a contract mandating that the winner’s next defense be against Norton. After Spinks won, “Neon Leon” violated the terms by choosing to fight Ali in a big-money rematch and the WBC responded by stripping Spinks and naming Norton its new champion on March 29, 1978. It was a distinction Norton accepted – reluctantly.

“At no time did I ever want to become known as a ‘paper champion.'” Norton wrote in “Going the Distance.”

Dogged by the criticism, and knowing what it felt like to be overlooked, Norton’s first defense came against the WBC’s new mandatory challenger – the 27-0 Larry Holmes. Though not widely known by the public at large, “The Easton Assassin” was no easy assignment. The 6-foot-4 Pennsylvanian stood one inch taller and his ramrod jab amplified his 80-inch reach, which was one inch longer than Norton’s. He also boasted excellent movement and an underrated right cross but his courage under the brightest lights remained untested. Any questions about Holmes’ mettle melted away that June night inside Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace and that was because Norton fought with the vigor, valor and vitality of a genuine champion, not a paper one.

Dogged by the criticism, and knowing what it felt like to be overlooked, Norton’s first defense came against the WBC’s new mandatory challenger – the 27-0 Larry Holmes. Though not widely known by the public at large, “The Easton Assassin” was no easy assignment. The 6-foot-4 Pennsylvanian stood one inch taller and his ramrod jab amplified his 80-inch reach, which was one inch longer than Norton’s. He also boasted excellent movement and an underrated right cross but his courage under the brightest lights remained untested. Any questions about Holmes’ mettle melted away that June night inside Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace and that was because Norton fought with the vigor, valor and vitality of a genuine champion, not a paper one.

Fighting with a left arm injured shortly before the fight, “The Easton Assassin” nevertheless rode his piercing jab to an early, and seemingly unassailable, lead. But Norton eventually closed the distance on Holmes both physically and mathematically with a determined power-laden assault. Entering the final round all three scorecards read 133-133.

The 15th round of Holmes-Norton remains among the most robustly dramatic three-minute segments in boxing history as the two men traded non-stop bombs and refused to cede an inch. At round’s end the roaring crowd gave both fighters a richly deserved standing ovation, for they had produced a performance that epitomized the term “championship boxing.”

Once again, the judges delivered Norton another heartbreak. Two of the three jurists awarded Holmes the final round and with it the WBC title.

Despite his crushing disappointment, Norton made time to speak briefly with ABC’s Howard Cosell immediately after walking down the ring steps.

“I made a big mistake by not applying pressure early in the fight,” Norton said. “I was going to try to make him expend himself in the first four or five rounds and try to come on heavy in the last rounds. It just didn’t happen so more power to Larry. It was a mistake on my part, and I paid for it.”

Few fighters, especially under those circumstances, would exhibit the blend of class, honesty and self-criticism. Those traits are an extension of the man himself, who always sought to improve himself in every way possible.

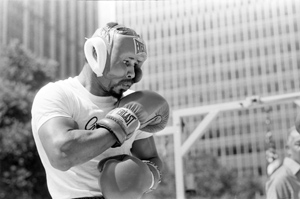

The physical accomplishments were obvious and impressive. He repeatedly said his exquisitely sculpted physique was not molded by weights but rather by genetics consolidated by hard work. That work ethic was molded while attending Jacksonville (Mo.) High School, where the defensive end and running back was a member of a state championship team who also excelled in baseball and track.

His football and track coach Al Rosenberger regularly entered him in eight track events. During one meet in the spring of 1961 against a powerhouse Decatur Eisenhower squad, Norton won six events and placed second in the other two. That result, and the vehement protests of the opposing coach, prompted the Illinois High School Association to adopt the “Norton Rule,” which limits athletes to a maximum of three events in state meets. Norton’s exploits earned him a football scholarship to Northeast Missouri State University (now Truman State University), where he also studied elementary education.

A series of shoulder injuries ended Norton’s football career and shortly thereafter he enlisted in the U.S. Marines. While there he turned to amateur boxing, where he compiled a 24-2 record and captured three All-Marine heavyweight championships. After being honorably discharged in September 1967, Norton turned pro two months later with a fifth round TKO of Grady Brazell. Norton won his first 16 fights, 15 by knockout, before losing to Jose Luis Garcia by eighth round KO.

Shortly after that fight Norton read Napoleon Hill’s motivational book “Think and Grow Rich,” which Norton said changed his life. He won his next 14 fights, the last of which was the landmark victory over Ali.

Like Stan Musial with his corkscrew batting stance, Norton confounded his opponents – especially Ali – with his contorted crab-like defense and his looping, powerful blows. Unlike most fighters who can be defined by a single punch – Joe Frazier with his left hook, Thomas Hearns with his right cross and Larry Holmes with his jab – Norton couldn’t be labeled so easily. Some say his best weapon was his overhand right while others pinpointed his left hook. Norton said in an interview with THE RING that the right uppercut that shredded Jerry Quarry was the single hardest punch he ever landed. Howard Cosell often pointed out how Norton dragged his right foot behind him and how his off-kilter rhythm affected his opponents but Norton, more often than not, didn’t think of himself as a spoiler but rather someone who used his talents to find a way to win much more often than not.

Like Stan Musial with his corkscrew batting stance, Norton confounded his opponents – especially Ali – with his contorted crab-like defense and his looping, powerful blows. Unlike most fighters who can be defined by a single punch – Joe Frazier with his left hook, Thomas Hearns with his right cross and Larry Holmes with his jab – Norton couldn’t be labeled so easily. Some say his best weapon was his overhand right while others pinpointed his left hook. Norton said in an interview with THE RING that the right uppercut that shredded Jerry Quarry was the single hardest punch he ever landed. Howard Cosell often pointed out how Norton dragged his right foot behind him and how his off-kilter rhythm affected his opponents but Norton, more often than not, didn’t think of himself as a spoiler but rather someone who used his talents to find a way to win much more often than not.

His drive to win was complimented by his efforts to improve himself. Besides the inspiration he derived from Hill’s book – he won the Napoleon Hill Award for positive thinking in 1973 – his stint in the military instilled a higher level of self-discipline, teachability and work ethic. At the urging of his brain trust, Norton sought the services of a hypnotist to help him prepare for the first Ali fight, a move that obviously steeled his mind against Ali’s insults.

“I felt I was as smart as he was and I was more physical,” Norton told USA Today. “My manager thought a hypnotist would be a good thing. It gave me more of a positive feeling.”

Along with Joe Frazier, Norton is regarded as Ali’s greatest nemesis and that claim to fame, in part, earned him numerous awards following his retirement. He was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1989 and three years later he was enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota. Other honors include San Diego’s Breitbard Hall of Fame (2001), the United States Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame (2004), the WBC Hall of Fame (2008), the California Sports Hall of Fame (2011), a number 22 rating by THE RING in its list of “The 50 Greatest Heavyweights of All Time” and was twice named “Father of the Year” by the Los Angeles Sentinel as well as by the Los Angeles Times in 1977.

Norton’s versatility was further illustrated through his TV and film career. His speaking skills served him well as a ringside commentator and his overall look prompted directors to cast him in numerous TV shows as well as in approximately 20 films, most famously the 1975 movie “Mandingo” where he portrayed a fighting slave. Norton was Sylvester Stallone’s original choice to portray Apollo Creed (an ironic twist given Creed’s Ali-like characteristics) but after he withdrew Carl Weathers was selected for the part.

His athletic genes were passed on to his children, most notably Ken Norton Jr., a three-time Pro Bowler who played for the Dallas Cowboys and San Francisco 49ers between 1988 and 2000. Norton Jr. is now an assistant coach with the Seattle Seahawks. Norton is also survived by wife Rose Conant, sons Keith and Kenny John and daughter Kenisha. As of this writing, a memorial service in Orange County is being planned and he will be buried in his birthplace of Jacksonville, Illinois.

Throughout his life, Norton strove to be a complete human being who will be remembered fondly by those closest to him as well as by those who only knew him through sports. The successes can be found throughout the various layers of his life. As a young athlete he pushed the limits of his limitless potential. As a Marine he was trained to be always faithful to his mission and to his comrades. As a boxer he didn’t always win but he consistently put forth the labor demanded of a professional. As someone who was expected to perform for the TV and movie cameras he did his best to summon his best. As he endured multiple physical crises, he rose above his circumstances by being himself. And now that he’s gone, we are left to remember and honor the legacy he leaves behind.

For Ken Norton life’s fight is over, and this time one can fairly say his victory is unanimous.

*

Photos / THE RING

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.