Mike Tyson’s return against Peter McNeeley was a comedy with dramatic undertones

Look up the 1996 boxing movie The Great White Hype on Wikipedia and you’ll see that it is described on as an “American sports comedy” and “a satire of racial preferences,” inspired in no small part by Mike Tyson’s Aug. 19, 1995 return fight vs. Peter McNeeley.

Although the plot did not exactly mirror Tyson-McNeeley, the casting choices certainly seemed to directly apply to the real-life principals. There was Samuel L. Jackson as the Rev. Fred Sultan, a spot-on impersonation of Tyson’s bombastic promoter, Don King; Damon Wayons as heavyweight champion James “The Grim Reaper” Roper, the faux Tyson who like his character’s inspiration wasn’t nearly at the top of his game but didn’t really need to be against a no-chance opponent, and Peter Berg as Terry Conklin, the pale-hued designated victim who may or may not have believed that he had a snowball’s chance in hell of pulling off a colossal upset.

A sports comedy? It was certainly that all right, a cornucopia of unscripted giggles whose ramifications extended far beyond the actual proceedings at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand. McNeeley, who went down twice inside the first minute and a half of the opening round before he was disqualified when his manager, Vinny Vecchione, entered the ring to save his guy from further bludgeoning, capitalized on his brief flirtation with fame by accepting a $100,000 fee for appearing in a Pizza Hut commercial where he swallowed what remained of his pride and allowed himself to get knocked out by a slice of pepperoni. Tyson’s downward spiral was not always evident during his up-and-down journey on the comeback trail, but he reprised the McNeeley debacle with a United Kingdom equivalent in scoring a second-round stoppage of Julius Francis on Jan. 29, 2000, in Manchester, England. So inept was Francis – dubbed “Clown Jules” by one witty headline writer for a Brit newspaper – that he was floored five times in four one-sided minutes before cessation of the ongoing slaughter.

While virtually no one expected anything so incredulous as a McNeeley victory, or even a semi-credible performance by the “Irish Hurricane” from Medfield, Mass., the global hype for the non-event event was epic in scope. That was to be expected, given the fact that Mike Tyson, boxing’s biggest heavyweight drawing card since Muhammad Ali, was making his first ring appearance in 50 months, the long layoff attributable to the three years and six weeks he spent incarcerated in an Indiana prison after being convicted of the rape of a teenaged beauty pageant contestant. What would Tyson, the erstwhile “baddest man on the planet,” look like after his long enforced layoff from his pugilistic trade? Hundreds of millions of inquiring minds wanted to know. Not only did the “fight,” such as it was, attract a celebrity-infused full house of 16,736 spectators, but through the magic of satellite communications it was watched in 90 countries on six continents. The press section was jammed with over a thousand credentialed media members, some of whom came from as far away as Japan and Sweden.

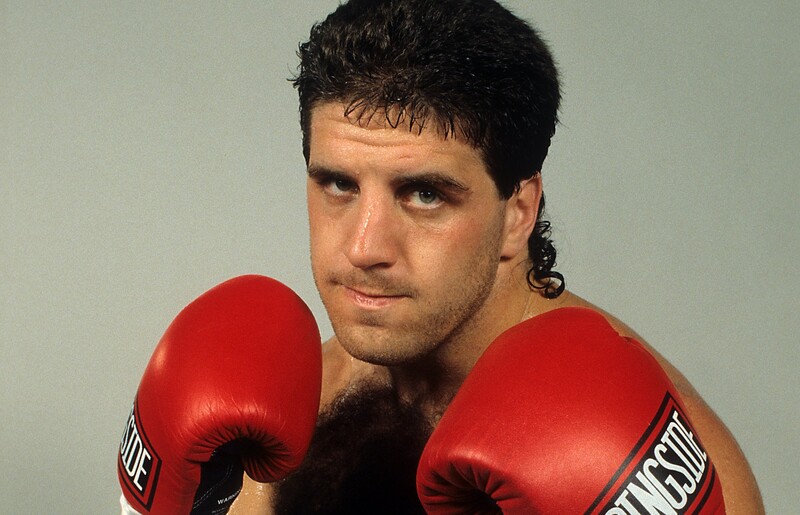

Cynicism, to be sure, was rampant among most reporters who refused to recognize the odd pairing as legitimate competition. One press wag described what surely was about to happen as a “tour de farce,” and I, part of the credentialed media throng, reflexively dismissed McNeeley, the “Irish Hurricane,” as “Peter the Not So Great” and more akin to a low-grade tropical depression. But, perhaps because of the myriad factors involved rather than in spite of them, the entire tableau of what took place, not only of the 89 elapsed seconds of the fight itself but its lead-up and aftermath as well, was and continues to be a source of wonderment.

Tyson, no longer a heavyweight champion as the result of his stunning, 10th-round knockout loss to Buster Douglas on Feb. 11, 1990, in Tokyo, stepped inside the ropes that night with a record of 41-1 with 36 victories inside the distance. Even after getting tuned up by Douglas and the serving of his prison stretch, the consensus opinion was that he was still an extremely dangerous dude who could, and very possibly would, reclaim his status as the foremost heavyweight on the planet. But even his most ardent supporters could understand the reasoning for not putting him in right away with a top-tier opponent, at least not until he underwent a shakedown cruise to scrape off any accumulated ring rust.

Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

Enter Peter McNeeley, who, on the surface at least, appeared to suit Tyson’s purposes at that time. For one thing, he was the son of former Michigan State football player Tom McNeeley, an ex-challenger of then-heavyweight titlist Floyd Patterson, who, like Tyson, had been groomed for stardom by cantankerous trainer Cus D’Amato. Presto, that immediately became part of the story line. So, too, was the fact that Tom McNeeley had been knocked down an astounding number of times by Patterson in their Dec. 4, 1961, bout in Toronto – eight or nine officially (both figures have been cited), although there were several more trips to the canvas that were perhaps incorrectly ruled slips by referee Jersey Joe Walcott, upping the total to 11 or 13, depending on which figure you choose to believe.

“The stories about the fight said I went down nine or 10 times,” Tom McNeeley, who was 74 when he died on Oct. 25, 2011, said in a 1994 interview with the Boston Globe. “The writers were being nice to me. I have the film. It was more like 12 or 13.”

However one calculates the arithmetic, Peter McNeeley’s pop was like a lamb being led to the slaughter against Patterson, much as his son figured to be against Tyson. Although Tom McNeeley was credited by New York Times writer Arthur Daley with having “flaming courage” in his spectacularly failed attempt to dethrone Patterson, Daley’s fight account allowed that Floyd “chopped him down with the methodical precision of a butcher going to work on an obstreperous steer.”

Given Tyson’s vast advantage in punching power in relation to Patterson’s, it was assumed that Iron Mike would not have to knock Peter down nearly so often to bring about an outcome that was all but a foregone conclusion. Still, it was necessary for the ruse to take on a veneer of acceptability that McNeeley have a spiffy record, even if it had been artificially assembled. No problem; a 22-1 underdog, he entered the ring with 36-1 mark and 30 wins inside the distance, and so what if the guys he had beaten were a bunch of no-names with a combined mark of 210-454-22? Perhaps due to King’s lobbying on his behalf, McNeeley had come almost out of nowhere to a No. 7 rating from the World Boxing Association.

Give King credit for the sort of advance planning that provided him with a deep enough roster of non-threatening heavyweights to be able to throw one into the deep end of the pool, with an anvil tied around his ankles, against one of His Hairness’ star attractions as the need arose. Toward that end King had signed McNeeley to a four-year promotional contract, which made him a veritable ice cream cone to be licked by Tyson. Give credit also to Vecchione, who had turned down offers to put McNeeley in with Joe Hipp (for $60,000) and Tommy Morrison (for $100,000, later upped to $125,000), in the expectation that a truly major score for his guy would be the reward for his exercising of managerial patience. Waiting proved the correct move as McNeeley’s purse for presenting himself to Tyson for target practice was $540,000, far and away his largest ever. Tyson was guaranteed $25 million, which could increase to $40 million in the pay-per-view revenues were sufficiently large, which they were.

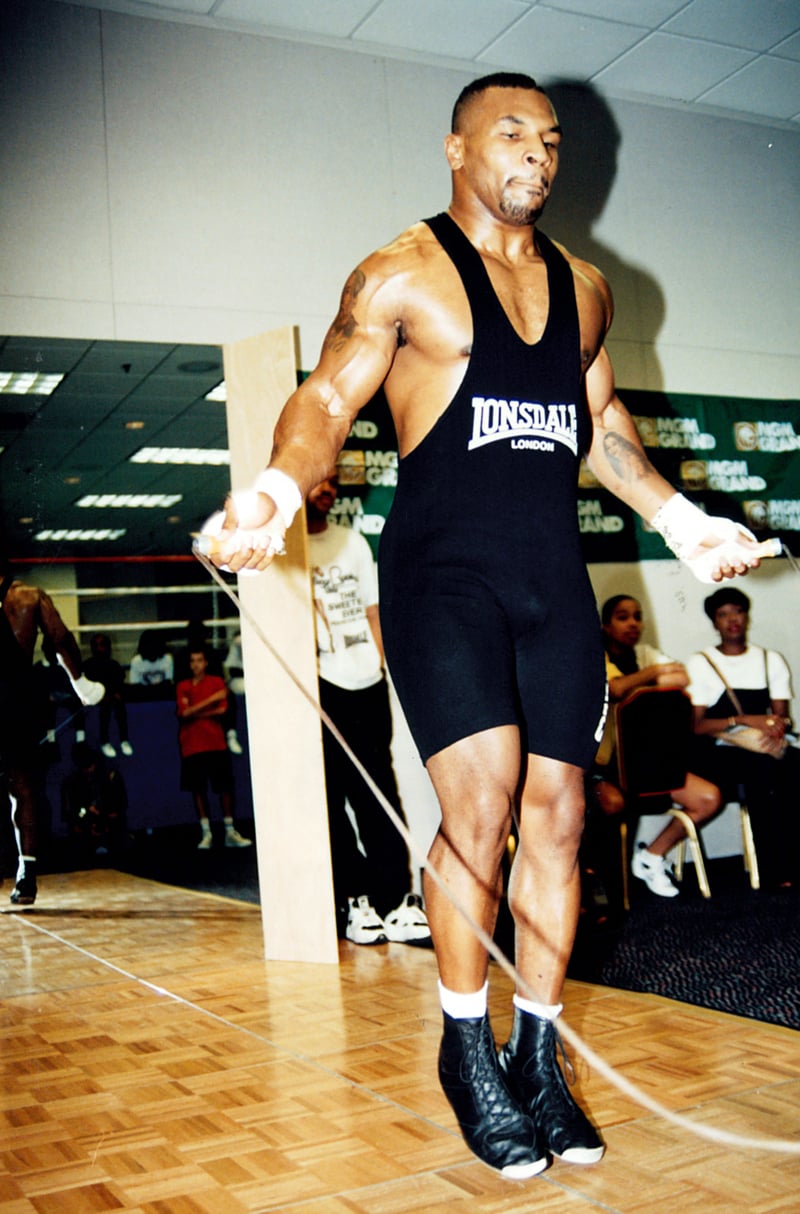

There was, of course, more work to be done to further peddle the story of Tyson’s return, against a no-chance foe, to a gullible public. In the immortal words of mid-1920s marketer extraordinaire Elmer Wheeler, if you can’t sell the steak, sell the sizzle. Toward that end, Showtime executive producer Jay Larkin concurred with the suggestion of Tyson’s co-manager, the wily John Horne, that Tyson be all but invisible in the weeks leading up to his ritualistic execution of McNeeley, the better to heighten the anticipation of actually seeing him do his thing on fight night.

“Several possibilities were discussed,” Larkin, who passed away on Aug. 9, 2010, said of the intentional shielding of Tyson from prying eyes. “We discussed putting a sparring session on Showtime. But the general consensus was if the public doesn’t see Mike in a ring until (fight night), the suspense and excitement and curiosity will be maximized.

“Just look at where he was four months ago (in a jail cell) and where he is now. I can understand why he might not want to be thrown into a feeding frenzy of reporters.”

Tyson training for McNeeley. Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

With Tyson safely sequestered, it fell to the chatty McNeeley, clearly reveling in his opportunity to the focus of such unaccustomed attention, to provide the litany of quotes and sound bites that kept the bout’s momentum going until the snarling Tyson, on cue, emerged from the shadows.

“I’m right in front of you all the time,” McNeeley told reporters. “I’m not running and hiding. I’m here to fight. Even people who don’t think I can win want me to win. I’m the people’s champion. I don’t hide out like the other guy. When someone comes up to me and asks for an autograph, I always try to be accommodating.

“Tyson is the draw, but I’m getting my name out there. Tyson can’t do it alone. I’m the other half of this show. I always knew my destiny was to be in a situation like this, a big-fight situation. Now that I’m here, I’m planning to make the most of it. I have good stats. I deserve this shot.”

But McNeeley’s most memorable phrase was and shall forever remain this bit of simplistic rhyming, uttered with the proper bit of bravado and panache at a press conference which drew howls of laughter from those in attendance: “I’m `Hurricane’ Peter McNeeley, from Medfield, Mass. Watch Saturday night, when I kick Tyson’s ass.”

During Tyson’s near-total absence from the media circus while in Vegas, reporters were left to scramble for someone, anyone, willing to speak on his behalf. That role was filled in part by Jay Bright, a onetime resident in Cus D’Amato’s Catskill, N.Y., house, who surprisingly had been appointed Tyson’s lead trainer only four weeks prior. Bright had never before served as the lead trainer for any fighter, and certainly not one of Tyson’s caliber, but he said his connection to D’Amato made him the right guy to wheedle whatever was needed out of a far more notable Cus acolyte.

“When Mike goes to his corner, he really has to trust the people there, especially after the long layoff he’s had,” Bright said. “He has to trust that those people will tell him the truth and, if need be, be brutally honest with him. Mike has that trust in me. He knows that what I’m telling him is what Cus would tell him if Cus were here.”

Bright’s depiction of himself as a D’Amato confidante drew snorts of derision from Teddy Atlas, who said, “You want to know what Jay really did in that house? He hung out with Camille (Ewald, D’Amato’s companion) and made quiche. I’m serious. He was a vegetarian and he made quiche and blueberry pies with Camille. Jay was not connected to the boxing group up there. He never pretended to be. He never went to the gym with us. He never ate with us. He’s insulting everyone’s intelligence, but especially Tyson’s, by saying he had any background in boxing.

“One thing I am adamant about is him lying about training fighters. He never trained one fighter. Now he thinks he can make up whatever stories he wants and nobody will call him to account. Well, I’m here to say Cus would be spinning in his grave if he knew Jay Bright was training Tyson.”

As it turned out, Bozo the Clown likely would have fared as well as Tyson’s chief second against McNeeley, who, true to his word, charged at the heavy favorite from the opening bell on what was tantamount to a suicide mission. Only seven seconds had ticked off when Tyson floored him with an overhand right, but McNeeley, as had been the case with his dad against Patterson, scrambled to his feet and attempted to bull-rush the clearly superior fighter to the ropes. He got him there, too, but again to no avail; Tyson fired two left hooks, neither of which landed flush, followed by a ripping right uppercut, which did. McNeeley went down again and once more beat the count, but he was on unsteady legs and primed to fall a third and no doubt final time when Vecchione rushed into the ring and wrapped his arms around his stricken fighter, giving referee Mills Lane no choice other than to wave off the remaining nine rounds plus 31 seconds of the scheduled 10-rounder. Originally ruled a TKO win for Tyson, the outcome was later changed to a DQ loss for McNeeley.

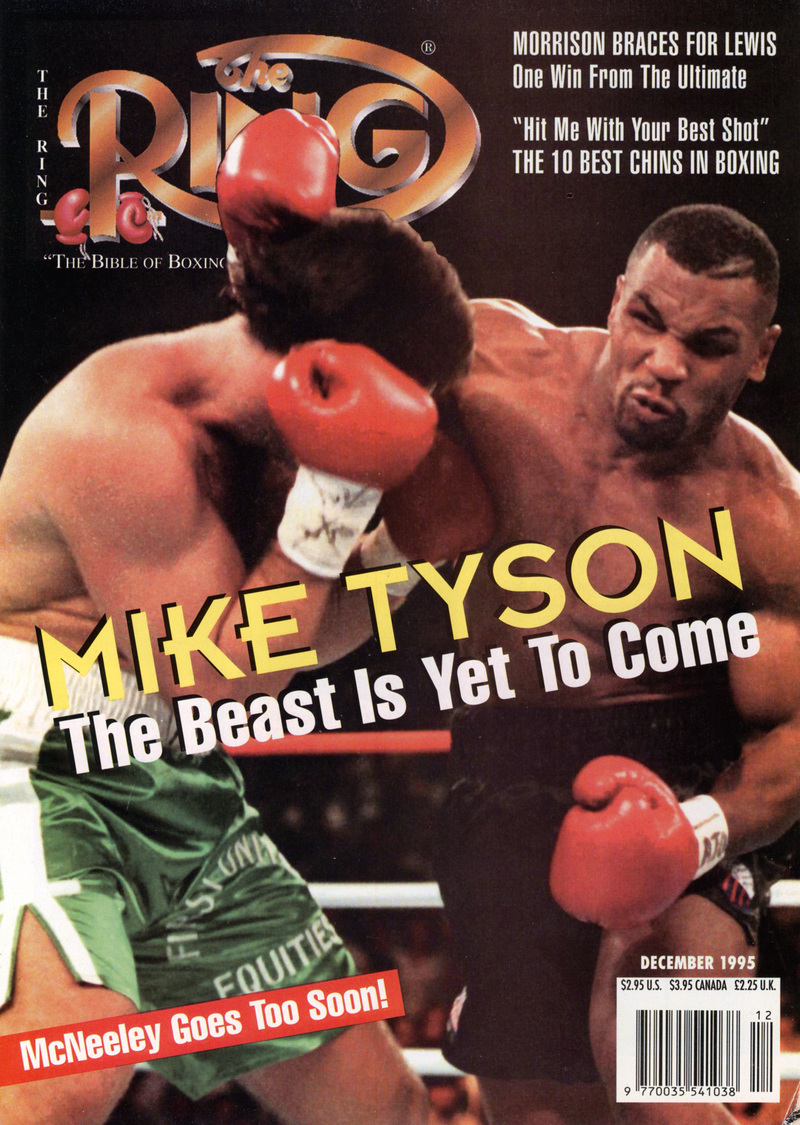

December 1995 issue

There were, naturally, shouts of “Bull—! Bull—-!” from spectators, more than a few of whom had paid $1,500 (some a lot more) for their ringside seats. The more vocal complainers may even have been from the celebrity contingent, which included such “A”-listers as Madonna, Bruce Willis, George Clooney, Jim Carrey, Jerry Seinfeld, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Magic Johnson, Shaquille O’Neal, Eddie Murphy, Denzel Washington and Larry Holmes.

Vecchione, who for a week had his share of McNeeley’s purse ($179,820) withheld by Nevada State Athletic Commission executive director Marc Ratner until it was released, insisted he felt obliged to do what he did. “I remember Jimmy Garcia (who died of injuries incurred in the ring) and Gerald McClellan (who suffered catastrophic, career-ending injuries),” Vecchione said. “The important thing is this kid’s 26 years old. He’s going to continue to fight. He gave you 100 per cent effort. If I made a judgment and I have to live with that judgment, so be it. As far as I’m concerned, I did the right thing by my fighter.”

During his time at the podium, King said what was then perceived as a travesty and still is was anything but. “People were not ripped off,” the promoter harrumphed. “I thought it was the best Tyson fight that I’ve seen. McNeeley attacked Mike Tyson. No matter what anyone says, he went after Mike like no one ever had. Usually, the guys Mike fights stand back, waiting to get knocked out. They’re scared and they run around. Peter McNeeley lasted as long as Michael Spinks, who was a three-time world champion. He lasted as long as Carl `The Truth’ Williams and Alex Stewart. In terms of longevity, you might not say that Peter rose to the occasion. But in quality of effort, Peter was the best Mike ever fought.”

Certainly Tyson was paid extraordinarily well for his 89 seconds of exertion. His $40 million take after the PPV numbers were included comes to $449,438.20 per second (before taxes), nice work if you can get it. Finally free to speak, the man-beast appeared to be more conciliatory toward than contemptuous of the fighter who had publicly vowed to kick his ass.

“I’m just happy I was lucky enough to win tonight,” he said. “I did OK. Praise be to God that we’re both OK and healthy.”

Years went by and there were other pages that were added to the postscript, not all of which qualify as the continuation of an American sports comedy. Tyson, his enthusiasm and dedication to his craft waning, went 8-5 with two no-contests in his final 15 bouts. The back-to-back losses to Evander Holyfield and one to Lennox Lewis, in retrospect, aren’t shocking; the stoppages at the hands of Danny Williams and Kevin McBride are stunning even today. It is left to boxing historians to debate whether the gradual unraveling of the scariest heavyweight of his era may actually have begun with his quickie demolition of the hopelessly outclassed McNeeley.

And what of McNeeley? Vecchione’s compassion did buy him some extra time to regroup and hopefully rebound, but he never again came anywhere close to anything approximating contention. His final record, on its face, remains reasonably respectable at 47-7, with 36 KOs, but his boxing legacy is marked nearly as much by his one-round stoppage at the hands of the “King of the Four-Rounders,” Eric “Butterbean” Esch, on June 26, 1999, as by his doomed dance with Tyson. Years later, McNeeley, in an interview with the Boston Globe’s Ron Borges, recalled how far and how fast he had fallen from his momentary prance across boxing’s center stage.

“A year after I fought Mike Tyson, I was sitting in a crack house digging for rocks that weren’t there,” McNeeley said. “I was peeking out of windows at demons that weren’t there. I was lost. I dropped out of life … the only people who stayed and believed in me were my mom and dad – and Vinny Vecchione. They loved me.”

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.