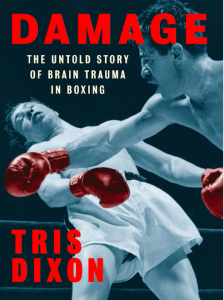

Damage: The Untold Story of Brain Damage in Boxing is must read for those in boxing biz

Tris Dixon loves boxing.

It’s important to point that sentiment out because there are those who will read his book “Damage: The Untold Story of Brain Damage in Boxing,” from Hamilcar Publications, and wonder why he would write about the sweet science’s dirty secret.

And it’s not because he hates the sport. It’s just the opposite.

“I took it on because I love boxing and I love the boxers and they’ve given me so much enjoyment over the last 25 years that I feel like I’m indebted to them for the sacrifices they’ve made for my entertainment over the years,” said Dixon, the former editor of Boxing News who has authored several books and now writes for The Ring and Boxing Scene, while also producing his popular Boxing Life Stories podcast.

“I’ve been personal friends with the likes of Aaron Pryor and Matthew Saad Muhammad, and I’m so proud to call them friends – and they’re gone, and I saw them deteriorate and I was close to them and it hurts me, and very little is ever done for these guys in boxing. So that’s been the chief driver.”

Pryor and Saad Muhammad were two of the greats, stars and champions during boxing’s last Golden Era in the 70s and 80s, but at the end, the sport had taken its toll on both of them. It was a stark reminder that the stereotype of the damaged fighter was not in line with reality.

You know the portrayal in pop culture: It was a fighter who was an opponent, a club fighter, someone with no defense and even less technique who left the sport with nothing in terms of health.

Pryor and Saad Muhammad were among the best in the game in their prime. And what about the trio of Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Robinson and Joe Louis? All legends, all who sacrificed their health to the sport. It’s as brutal a truth as you will find in any sport, and while Dixon pulls no punches in telling the history of brain trauma in boxing, there is also a compassion there as he tells the stories of the warriors who gave everything in the ring.

And in doing so, Dixon not only wanted to shatter stereotypes, but educate and try to get people in and out of the sport to show respect for everyone who walks up those four steps.

“I want punch drunk syndrome and punch-drunk terminology that’s been so derogatory over the years completely gone and abandoned, so that these fallen warriors are not mocked or made into laughingstocks any longer, but that they’re sympathized for the sacrifices they’ve made for the greater good of the greatest sport there is,” he said.

“Another reason I wrote the book is to educate people. I’ve been in boxing 25 years and only recently did I know what CTE and tau protein was. Did I know the links to behavioral changes as much as physical? When we talk about fighters who suffer from punch drunk syndrome, we are talking about guys who notoriously walked with a stagger in their steps, or they have slurred speech. But what people didn’t know is that depression in boxing’s a big thing, but that can actually be linked to brain trauma, as can impulsivity and poor business decisions. And we’ve seen the stereotype played out for years of boxers having everything then losing everything. Were these bad business decisions? Sure. Were they bad decisions or bad decisions owing to trauma? We just don’t know. But it’s a conversation we all need to have and a subject we all need to be far more aware of than we presently are in the sport.”

Arturo Gatti (L) and Micky Ward fought three times. Gatti is gone and Ward freely admits that head trauma impacts him tremendously. (Photo by Al Bello/Getty)

There has been no shortage of news regarding chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) over the past several years when it comes to American football and ex-players who suffered (and are suffering) from it.

But it’s only recently that it’s hit the headlines in boxing, even though it’s been studied in the medical field a lot longer.

Subsequently, the NFL, along with other sports leagues, have had to address it publicly, but in boxing, it’s still a case of stick your head in the sand and hope it goes away.

That’s where the media comes in, and Dixon believes all of us on the other side of the ropes need to address the presence of CTE in the sport.

“I think we’re all part of the generation where it’s our responsibility to do so, to make the fighters aware, to make the people reading our stuff aware,” he said. “If we don’t, we’re gonna be leaving the job to the next generation, when we have the information now available to us which maybe our predecessors didn’t unless they were really rooting through medical journals. We have no excuse to hide from it any longer. And we have no reason to be ashamed of it. It’s boxing’s problem. Football, soccer, rugby, they’re all taking it on in some way, shape or form. But boxing shrugs its shoulders and goes about its business.”

That’s the sad part, but as Dixon points out in “Damage,” it’s been like this since boxers put on gloves and punched each other for pay.

“These guys deserve so much more respect than they get when they hit the end of the line and they do wind up with nothing,” he said. “It’s heartbreaking. And they put everything on the line, not just for our entertainment, but to give themselves a better life, to give themselves a shot at success and to possibly turn their lives around. And when it doesn’t work out, these guys deserve our sympathy, care and support and not to be mocked or laughed at.”

Thankfully, along with the comprehensive history of these issues from a medical point of view, Dixon was able to get so many fighters to talk about the topic so many shy away from. And while he says he had no issues with fighters opting to pass on discussing such matters, he will say there is an asterisk attached to that answer.

“Quite a few of the guys who are damaged, and the guys who haven’t yet shown symptoms, yes, there’s that whole thing of, ‘I think I got out at the right time,’ and that kind of thing which is there,” Dixon said.

Befriending various fighters has allowed Dixon to acknowledge the depth of damage blows to the head can cause. Here, Dixon poses with Ward (left).

“But there’s also a lot of guys who have physical signs I can detect, but that they don’t know that they’ve got, or that they won’t admit to having. That’s a side of it. And this is one of the reasons why I felt the book was necessary. It got to the point where I was thinking if I’m in a room with a hundred people, I could pick out two ex-fighters within five minutes because you can tell how they walk and how they act, and their mannerisms and that kind of stuff. And I was thinking, I have a trained eye to it and a trained ear to it, but no one’s really talking about this, but there’s something going on.”

So what’s to be done?

Dixon lays out the opinions of the top medical professionals in the field, but all that information is useless if the boxers, trainers, managers, promoters and commissioners don’t take it in and implement it.

“These are all the facts,” he said.

“And it’s really up to boxing to get in front of the curve with all of this rather than be reactive. It’s got the opportunity to change policies, procedures, stigmas, the media representation. It can get in front of the curve; it’s just gonna take a bit of joined-up approach with the major players in the sport. And I think a lot of it comes down to knowledge and education in terms of trainers and managers, and the fighters themselves. And it’s the amount of exposure, the sparring and the fights. That’s what it boils down to. Very few of these guys have had 30 fights in their career and then they’re damaged. And of course, there’s plenty of outliers, like George Foreman, that don’t show any signs.”

Dixon points out the amateur system, where some have been fighting in hundreds of bouts since they were five or six years old. Or what about commissions that don’t follow the rulings of fellow commissions, allowing a fighter suspended in one state to fight in another? Or the way we celebrate gym wars when someone like Micky Ward believes 90 percent of the damage done to him came in sparring?

“They say you shouldn’t be heading a soccer ball under the age of 14,” said Dixon. “Well, if that’s the case, then maybe boxing needs to double check it’s starting age of punches to the head. And then obviously you’ve got the end game, which is the most depressing age. I’ll use Ali as an example where he was done and everyone knew he was done, but he could still slip through nets in the Bahamas and go and box there. These loopholes need to be closed up fully for the sake of the boxers and their well-being. And how necessary is it for these guys to go life and death three, four, five times a week in sparring? There’s plenty we can do to get in front of the curve. It’s just whether boxing wants to do it and make this a situation it does want to deal with.”

Is Dixon hopeful that change – or at least awareness and prevention – will come? “I’ll always be hopeful.”

As Thomas Hauser pointed out in his recent review for BoxingScene.com, ‘Damage’ “is an important book.”

I second that, adding in even stronger terms that this is a book that should be required reading for anyone involved in boxing. It’s not an easy read, and upon finishing it, you may look at the sport in a different way. But that’s necessary. I know many of us have loved a great fight, but after the adrenalin wears off, we wonder what the morning after will be like for two battlers who left it all in the ring the night before. Tris Dixon has had those feelings, but this is his way of paying tribute and trying to help the ones who step through the ropes and risk it all.

“I suppose that was a trigger to why I started to look at life after boxing for fighters, to see what the damage was down the line, and subconsciously maybe that’s why I went away from working in a full-time position (with Boxing News), so I didn’t have to deal with it on an absolutely daily basis 24/7,” Dixon said.

“But then you factor in the other stuff and why we do it, and you think about these guys and the lives they’ve been able to live through fighting. You think about how these guys’ lives might have panned out had they not had boxing. You think about how many lives boxing’s saved and how many guys it’s given a discipline, a routine and a real way out. I know it’s a cliché, but it’s given these guys a lot of hope when previously there was none. You need to weigh up the good and the bad, and for me, boxing will always do more good than bad.”