Marco Antonio Barrera-Kennedy McKinney: Fire at the Forum 25 years later

Twenty five years ago today, Marco Antonio Barrera and Kennedy McKinney produced a slugfest for the ages that transcended the original “budding superstar versus aging former champ” storyline. It was a match fueled by anger, passion, pride and ambition, so much so that the loser received a tribute fit for a “King.”

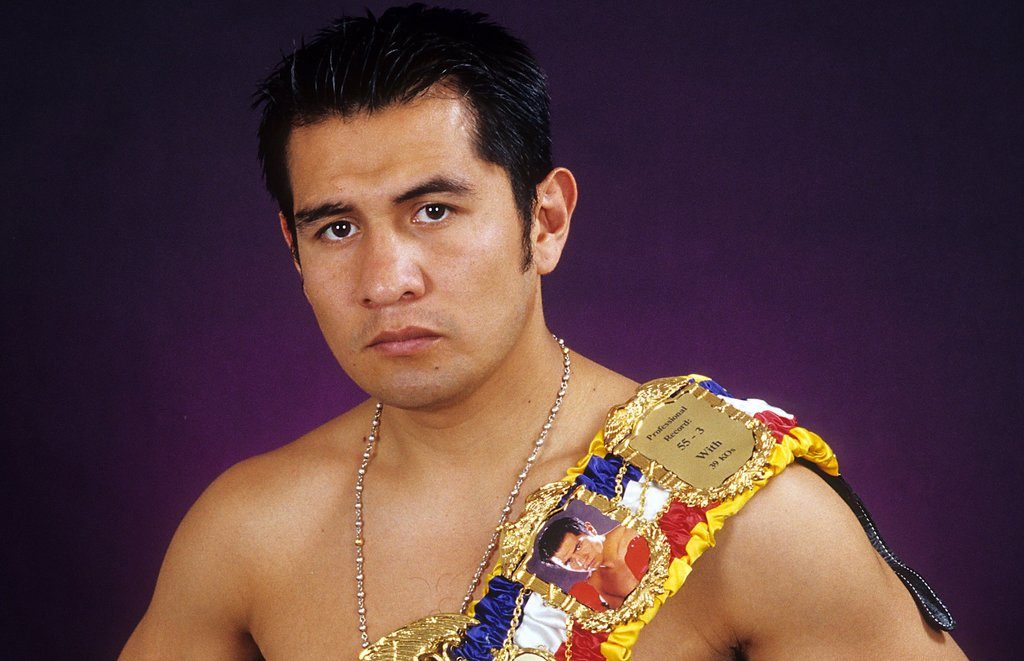

Barrera-McKinney was the first main event of a new HBO boxing series entitled “Boxing After Dark,” a groundbreaking late-night program whose mission statement was to showcase fighters who normally wouldn’t be considered for the “HBO Championship Boxing” franchise but who also were viewed as “too big” for the basic cable platforms. On paper, Barrera-McKinney was the perfect pairing for the series’ debut. The 22-year-old Barrera — the defending WBO junior featherweight titleholder — was a recent pound-for-pound entrant who was being favorably compared to Mexican legend Julio Cesar Chavez thanks to his 39-0 (27 KOs) record, his polished aggressiveness and his devastating two-fisted power. Meanwhile, the 30-year-old McKinney (28-1-1, 17 KOs) was a 1988 Olympic gold medalist and a former IBF junior featherweight titleholder who was viewed as being on the downside of his career, mostly because of his stunning points loss to Vuyani Bungu that was deemed The Ring’s 1994 Upset of the Year. McKinney had fought just once since that loss, an eighth-round TKO over the previously undefeated John Lowey in August 1995, but despite the victory and his accomplishments at the championship level he was still viewed as “the other guy” in the Marco Antonio Barrera show.

McKinney sought to change that viewpoint at a press conference staged the Tuesday before the match. During his remarks, he turned toward Barrera, who was seated less than three feet away to his right and slightly behind him, and began yelling at him.

“I have a wife and a house and a car; bills I’ve got to pay, and I DARE for you to come here and think you can beat me!”

At this, the stone-faced but somewhat puzzled Barrera rose out of his chair and faced McKinney head on, a move that raised the room temperature considerably. As someone else on the dais stepped between the pair and used his left arm to create a barrier, McKinney, determined to carry through his plan, persisted.

“You think you can beat me, boy? You cannot beat me,” he declared. “You cannot whup me here in my town!”

Just as McKinney began his next sentence, Barrera, who looked toward someone to his right a moment earlier, suddenly lashed out with a lead right hand that barely missed the American’s chin. At that point, the press conference was effectively over, and McKinney, who didn’t retaliate, left the proceedings thoroughly satisfied because he accomplished his primary goal: Rattling Barrera’s cage.

With the fight being staged at the Great Western Forum — the site of such celebrated battles such as Carlos Zarate-Alfonso Zamora, all three Ruben Olivares-Chucho Castillo bouts and Albert Davila-Frankie Duarte 2 — the subliminal message was that this was to mark Barrera’s ascension into the Mexican boxing pantheon. Yes, Barrera had fought at the Forum on eight other occasions but this was his first championship fight inside the historic building, and though McKinney was the underdog he still was the best opponent of his six-year career. Because of McKinney’s pedigree, power and pugnacity, he would provide the perfect acid test in terms of whether Barrera could make real the potential that was projected for him. With the inevitable decline of Julio Cesar Chavez Sr. and the stunning seventh-round TKO loss of Humberto “Chiquita” Gonzalez against Saman Sorjaturong in this same building the previous July, the Mexican public was searching for its next hero and boxing fans in general were hoping to see the birth of a new superstar. As for McKinney, he dearly wanted to regain a measure of what he lost to Bungu and to shut the mouths of those who doubted his viability as a top-shelf fighter.

Although Barrera was eight years younger he had fought nine more fights thanks to having turned pro a month before his 16th birthday. But McKinney had advantages as well; at 5-foot-8 he was three inches taller, his 72-inch wingspan was four inches longer than the champion’s and while Barrera campaigned at 115 and 118 before settling at junior featherweight, McKinney began his career at featherweight and weighed as much as 129 (KO 2 Reggie Johnson on April 21, 1990) before boiling down to 122 to begin his championship campaign. For the record, Barrera scaled 121 to McKinney’s 122 but in the dressing room shortly before the bout Barrera had rehydrated to 133 while McKinney weighed 131.

Photo from The Ring archive

Harkening back to his Olympic roots, McKinney entered the ring to the music played during the 1988 games on NBC while Barrera’s arrival was greeted by traditional Mexican music as well as with thunderous cheers from virtually all of the 7,912 fans. In a nod to the game between the Los Angeles Lakers and the homestanding Chicago Bulls (which the Lakers would win 99-86), McKinney wore a Earvin “Magic” Johnson jersey, but that did nothing to cut into the heavily pro-Barrera bias as the partisans chanted “Mexico! Mexico! Mexico!” throughout the final instructions. For those old enough to remember, those chants revived memories of the Mexican greats that had previously graced the Forum ring such as Pipino Cuevas, Lupe Pintor, Guty Espadas Sr., Gilberto Roman, Vicente Saldivar, adopted son Jose Napoles, and, of course, Chavez Sr.

The monstrous 24-foot square ring made the fighters look even smaller than they were, and once the opening bell sounded McKinney sought to utilize every square inch as he opened on the move, fired plenty of jabs and kept a sharp eye on Barrera’s left hook. But while Barrera missed plenty with the hook, he landed well with a series of right hands that yielded only a derisive smile. As Barrera continued to attack, the crowd chanted “Duro!,” which translates to “Hard!” in English, as in “hit him hard!”

In less than 90 seconds, McKinney’s rapid movement had slowed enough to establish the fact that this would be a face-to-face, toe-to-toe battle of skills and wills. The fast pace caused McKinney to start breathing heavier while Barrera’s facial expression, as usual, projected total focus. The action steadily intensified in the final minute and while McKinney’s face was more expressive, his chin, as well as Barrera’s, passed the initial test.

Between rounds, McKinney’s trainer Kenny Adams, a Marine drill sergeant in his younger days, advised his charge to work the jab even more, keep his hands up after finishing his work, to not rush so much, and to pivot to the right to avoid Barrera’s counters. Adams set the bar high, for McKinney landed 28 of 69 jabs, out-threw Barrera 88-67 and trailed just 38-36 in total connects in the opening round. Barrera, meanwhile landed 33 of his 55 power shots, and, given the potency of his fists, McKinney was courting disaster by being struck so often.

Fifty-one seconds into Round 2, Barrera connected with a hook to the body that caused McKinney to flinch, and the challenger’s reaction to follow-up hooks to the body and head told him that his quarry was stunned. Barrera landed a volley of power shots, but, tellingly, McKinney not only managed to weather the storm but also to force Barrera to back off and reset. A pinpoint uppercut to the face caused Barrera’s face to briefly register pain less than a minute later, and most of the round was waged at a distance more conducive to McKinney’s long-armed boxing. That allowed several sharp right hands to get past Barrera’s guard in the round’s closing moments, a round that still saw Barrera out-land McKinney 33-23 overall but a round that confirmed that McKinney would not be easy pickings for anyone, much less a budding star like Barrera.

The tit-for-tat boxing continued in the third, and because McKinney was giving as good as he got — if not better — the audience settled into an anticipatory buzz. One indicator of McKinney’s early control was that he firmly established his jab; through three rounds he landed 62 of 171 (36%) while Barrera was 32 of 67 (48%). For glass-half-full Barrera fans, their man was being patient but more pessimistic adherents would counter by saying McKinney was imposing his kind of fight on Barrera instead of the other way around.

The fourth saw McKinney work his jab even better (20 of 48, 42%), which, in turn, opened avenues for his heavy right cross. But Barrera, despite his tender years, remained composed and calculating, confident that he would eventually find the answers to the questions McKinney posed.

One piece of Barrera’s solution was aiming more to the body, but many of his attempts strayed below McKinney’s belt line. Another was landing counter rights, and those punches connected with increasing accuracy and impact. But McKinney’s ability to keep Barrera pinned along the ropes and to force him to circle away while at ring center projected an air of control, and a series of sharp right hands only added to the sour brew McKinney was producing. A barrage of blows in the final 20 seconds enabled Barrera to finish the around ahead 42-34 overall and 25-14 power, the fourth consecutive round in which the Mexican forged an advantage on the stat sheets. But make no mistake, no man had yet established full control of the contest.

Photo from The Ring archive

HBO analyst Larry Merchant spoke for many when he declared the following after round four: “Folks, this is about as good as it gets.”

The good news was that it would only get better.

Urged by Adams to push Barrera back, McKinney did so by working his jab overtime and forcing Barrera to search for alternate routes to get inside. Once the action moved into the trenches, McKinney fought well enough to negate Barrera’s advantage, and the result was a 33-27 lead in total connects thanks to his 21-11 gap in landed jabs. McKinney’s strategic success was the cornerstone of Adams’ fight plan, for he equated this fight to the Thomas Hearns-Pipino Cuevas match in which Hearns, the taller boxer-puncher, declawed Cuevas with his piston-like jabs and his ability to force Cuevas backward.

Through five rounds, McKinney confirmed that the best version of himself on this day was inside that ring, and because of that, it was up to Barrera to show that his best version of himself was up to the challenge.

The sixth was ferociously waged; both men fired their heaviest artillery but each delivered their blows with forethought and skill. McKinney’s left eye showed signs of swelling while Barrera, at times, looked a bit weary, but when the pair decided to simultaneously dig in, the action they produced was exhilarating, pulsating and punishing. The only question was which man would break under the pressure.

With 30 seconds left, Barrera forced out the answer. A barrage of power shots caused McKinney to totter across the ring and for the crowd to bellow in approval. Despite being buzzed, McKinney worked his way to ring center and planted a flush right on Barrera’s jaw. That jaw absorbed the impact unflinchingly, and it held up under another huge right moments later. Then, almost improbably, Barrera unleashed a final burst of blows that backed McKinney to the ropes. In a fight filled with outstanding rounds, the sixth served to raise the bar even further.

The CompuBox numbers further illustrated the round’s savagery: Barrera went 62 of 113 compared to McKinney’s 42 of 77, which translated to 55% accuracy for both men. Of the 190 total punches thrown, 152 were either hooks, crosses or uppercuts.

With the fight halfway done — and with the intensity red-lining — Merchant asked a salient question: Can McKinney, at age 30, maintain the hot pace? With the swelling around his left eye worsening and with blood filling his mouth, that was an open question. As for Barrera, he opened the seventh with the same fervor as he ended the sixth, and while McKinney was responding well, the long-term pendulum was swinging heavily toward the youthful power puncher and away from the experienced boxer-hitter, especially because the legs that had carried him so nimbly in the early rounds were significantly stilled.

That said, McKinney’s reservoir of courage was not yet exhausted. So while his gas tank was inexorably descending toward empty, the realization that his career was in a “now or never” state commanded him to empty his reserves. With Mexican icon Chavez Sr. at ringside, Barrera had every reason to unleash the totality of his weaponry.

Merchant, ever the sage wordsmith, encapsulated the fight best when he said the following: “This is the best of an American-style fighter versus the best of a Mexican-style fighter, and it is as good as you can hope for.”

The storm of the seventh receded to an unsteady calm in the first 115 seconds of Round 8 as McKinney reasserted his long-range boxing, Barrera shifted into wait-and-see mode and the crowd sought to catch its breath. But with 65 seconds remaining — and just moments after Barrera absorbed a big right to the chin along the ropes — the tenor of the fight shifted violently as Barrera sprung forward and connected with a heavy right to the jaw followed by a stiletto-sharp left to the body that drove McKinney to the floor. The composed challenger waited until referee Pat Russell counted seven to spring to his feet, but it didn’t take long for Barrera to score a second knockdown with an extended fusillade of blows. Again, McKinney regained his feet, and he somehow survived Barrera’s all-out assault for the round’s final 20 seconds to remove the three-knockdown rule from the equation.

“All I could do was pull up my bootstraps and get back up,” McKinney said in reference to how he rode out Barrera’s assault.

McKinney returned to amateur roots that numbered more than 200 fights in the ninth as he used as much of the expansive ring as he could while landing enough accurate right hands to tell Barrera he was still dangerous. Barrera continued to move forward but he also showed enough maturity to pick his spots, and the spots he chose were openings for overhand rights. The crowd booed McKinney’s tactics and Barrera’s inability to consolidate his advantage, but with one minute remaining the jeers turned to cheers as Barrera trapped McKinney along a neutral corner pad and scored the fight’s third knockdown with a flurry highlighted by two rights to the jaw. This time, McKinney popped to his feet immediately and assured Russell he was fit to fight. Russell agreed, but warned the challenger that he had to “show me something.” McKinney showed enough to get through the round, but with blood coming out of his nose the facial damage was only increasing and his 19 total connects in the ninth was his lowest total to date.

As per California rules in situations such as these, the break between rounds nine and 10 was extended by 40 seconds to allow doctors to conduct a thorough enough examination to ascertain McKinney’s state while also providing his corner adequate time to tend to their charge.

The rest did McKinney good, for he connected with an excellent right to the jaw a little more than a minute into the 10th. Suddenly, it was Barrera who looked tired and shaken and it was McKinney who appeared re-energized. The effects of this plot twist extended to the crowd, which had been on the edge of euphoria just a few minutes earlier but was now expressing alarm. HBO blow-by-blow commentator Jim Lampley sagely recalled McKinney’s off-the-floor title-winning victory over Welcome Ncita in December 1992 as evidence of the American’s recuperative powers, and, at least for now, those echoes were being reawakened.

McKinney continued the assault despite having his mouthpiece knocked out. Russell stopped the action with 15 seconds remaining to have the gum shield restored, a move McKinney (and Olympic teammate/ HBO analyst Roy Jones Jr.) protested because he felt it interfered with his positive momentum, momentum illustrated by his leads of 34-27 overall and 29-14 power.

With the finish line clearly in sight — and because both were gearing up for a potentially furious finish — the 11th began as an intense long-range boxing match in which the jab was dominant. But McKinney had another trick up his sleeve, for he used the relative lull to pivot hard to his right and connect with a hammering right that nailed an off-balanced Barrera and caused him to touch the canvas with his right glove. Russell correctly ruled a knockdown — the first of Barrera’s career. The champion instantly regained his senses and his footing, and the pair resumed their jabbing contest for the remainder of the round, a round that saw Barrera land 21 of 47 jabs compared to McKinney’s 21 of 41.

Entering the final round, Barrera had a commanding 106-100 lead on all three scorecards, and despite his improbable rally, McKinney’s trainer accurately gauged what his charge needed to do in the final three minutes: Knock out Barrera. But it was Barrera who struck first as a combination of a body hook and the slippery Budweiser logo contributed to an official knockdown just 18 seconds into the stanza. Moments later, Barrera appeared to score a legitimate knockdown with a searing hook to the liver, but because Russell interpreted the punch as a low blow he helped McKinney to his feet and allowed the fight to continue.

Barrera, however, knew McKinney was ready to be finished, and that finish came thanks to a pair of heavy rights to the chin that led to the fifth official knockdown as well as the instant end of the fight. The time: 2:05 of Round 12.

As the crowd cheered and as Team Barrera celebrated with their charge, Russell paid tribute to “King” McKinney’s courage by saying “that’s a great fight son….you’ve got the best heart I’ve ever seen.”

In all, Barrera landed 436 of his 875 punches (50%) while McKinney connected on 359 of his 815 punches (44%). Despite the anger Barrera felt for what McKinney did at the Tuesday press conference, he went out of his way to hug his rival. Both men spoke of a rematch, and Team McKinney’s initial plan was to regain the IBF title from Bungu, then challenge Barrera in a unification fight.

The good news was that McKinney fought Bungu 14 months later.

The bad news was that Bungu retained his title by split decision.

One would have thought McKinney’s time at the top of the sport would have ended with the second Bungu defeat, but that wasn’t the case as he would fight for another belt in December 1997. Victories over former titlist Hector Acero Sanchez (W 12 just 31 days after losing to Bungu) and Luigi Camputaro (KO 5) earned him a crack at the same WBO junior featherweight title for which he fought against Barrera. This time, the champion he faced was Junior Jones, who captured the belt from Barrera in upset fashion via fifth-round disqualification in November 1996 and defended against Barrera by 12-round decision the following April. Like the Barrera match, McKinney was the underdog, and after suffering a third-round knockdown one would have thought the end was near. Those who thought that ended up being right, but it was McKinney who ended the bout in explosive fashion as he stopped Jones in Round 4 with a trademark right hand. As incredible as McKinney-Jones was, it wasn’t even the best fight of the night as Naseem Hamed and Kevin Kelley somehow managed to top it by producing a combined six knockdowns in less than four rounds before the “Prince” emerged victorious in his much-anticipated U.S. debut.

McKinney vacated the belt in order to pursue a championship at 126, but WBC featherweight titleholder Luisito Espinosa proved too big, too strong and too powerful for him as the fight ended just three minutes and 47 seconds after it began. After going 3-2 in his final five fights — the last of which was a six-round decision loss to Greg Torres in March 2003 — the 37-year-old McKinney retired with a 36-6-1 (19 KOs) record.

As for Barrera, his story would continue for another 15 years. He would engage in a celebrated trilogy with Erik Morales, score a career-reviving victory over Naseem Hamed, and register victories over the likes of Johnny Tapia (W 12), Paulie Ayala (KO 10) and Rocky Juarez (W 12, W 12) while also falling twice to Manny Pacquiao (KO by 11, L 12) and Junior Jones (LDSQ 5, L 12) as well as once to Amir Khan (Tech Loss 5). Unlike McKinney, Barrera capped his career with a victory, specifically a second-round TKO over the 17-1 Jose Arias in February 2011 that lifted his final record to 67-7 (44 KO). Barrera was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2017 along with his fellow “Baby Faced Assassin” Johnny Tapia and four-time heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield.

YOU MAY HAVE MISSED

FLOYD MAYWEATHER-DIEGO CORRALES: PRETTY BOY PERFECTION 20 YEARS LATER

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 19 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.