Fifty years after shocking Jose Napoles, Billy Backus accepts role as Carmen Basilio’s sidekick

Batman had Robin, the Lone Ranger had Tonto and Sherlock Holmes had Dr. Watson. All things considered, there are worse things than to be a lesser partner with greatness, but forever in close proximity to it.

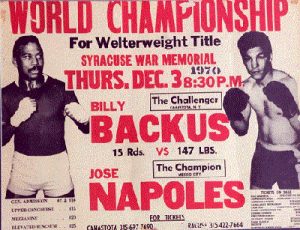

Fifty years ago today, on December 3, 1970, Billy Backus, the second-favorite boxing son of Canastota, New York, authored one of his sport’s most memorable upsets when, as a 9-1 longshot, he dethroned legendary welterweight champion Jose Napoles in War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse, New York, just 20 miles or so from the house in which Backus grew up.

“Napoles was the Superman of the welterweights,” Backus, now 77, once said of the near-Mission Impossible with which he was tasked. “He scared a lot of guys, but he didn’t scare me. I’d been in the ring with my share of tough guys, and, of course, I’d studied films of him. He was a very good puncher, a sharp puncher. But how was he going to react when I punched him back?

“Napoles was the Superman of the welterweights,” Backus, now 77, once said of the near-Mission Impossible with which he was tasked. “He scared a lot of guys, but he didn’t scare me. I’d been in the ring with my share of tough guys, and, of course, I’d studied films of him. He was a very good puncher, a sharp puncher. But how was he going to react when I punched him back?

“I gave him a couple of shots to the ribs and I heard him (groan). That’s all you need to hear when you hurt somebody a little bit. I don’t think he expected to get some real punishment back. He probably thought he was the superstar and I wasn’t supposed to be a threat to him.

“When you find out the other guy hits back hard enough to hurt you, then it’s a different program, and it’s not your program.”

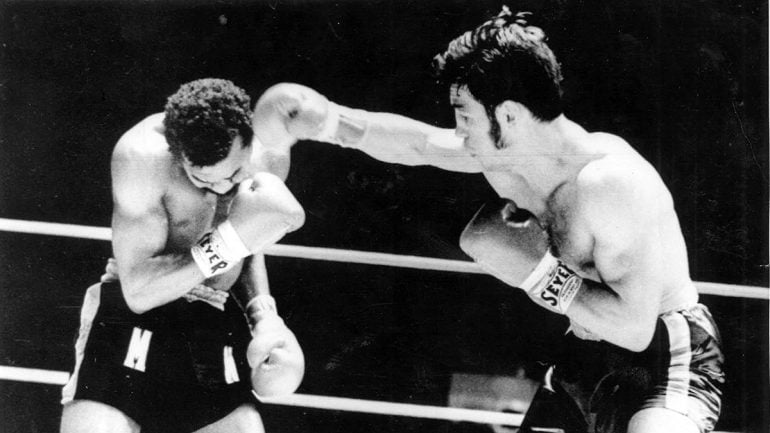

After a terrific, back-and-forth third round, Backus, a southpaw, stung Napoles with a right hook. A bit later in the round, another right hook opened a laceration above Napoles’ left eye that was severe enough for referee Jack Milicich to step in and stop the bout.

Backus’ more celebrated uncle, former welterweight and middleweight champion Carmen Basilio, went over to Napoles’ corner to have a look and was startled by what he saw. “He told me, `Wow! You can see the eyeball through the cut,” Backus said in 2015, on the 45th anniversary of the victory that will forever stand as the high point of a good but not indisputably great ring career. “But I wasn’t looking to stop him on a cut. I wanted to knock him out with a right hook, like the one that caused the cut. I wanted to put him down and out.”

For someone who had come up the hard way, overcoming a nondescript 8-7-3 (four wins inside the distance) pro start that more suggested a bumpy back road as a trial horse than an open highway to legitimate contender status, Backus’ optimism at the time may have been a bit excessive. After winning two non-title bouts, against Bobby Williams and Robert Gallois, Backus’ first defense was a rematch with Napoles, on June 4, 1971, at the Forum in Inglewood, California. This time “Mantequilla” reclaimed his title on an eighth-round stoppage.

Hedgemon Lewis and Billy Backus go at it at the War Memorial Auditorium,in Syracuse, New York in June 1972. Photo / The Ring Magazine via Getty Images

There are advantages, of course, to being a former world champion with a TKO victory over the likes of Napoles – a charter inductee into the IBHOF in 1990 who was 79 when he passed away on August 16, 2019 – on his resume. Backus got three more shots at a welterweight title, losing twice to Hedgemon Lewis for the New York State Athletic Association version, and, in his final bout, by second-round stoppage to WBA ruler Pipino Cuevas on May 20, 1978. He retired with a record of 48-20-5, with 22 KOs. Although he has returned to Canastota during the second week of June for the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s induction festivities nearly every year since the first such occasion in 1990, it always has been as a “special guest,” the nice local boy who had his moment of glory but not a body of work special enough to merit a plaque hanging on a wall of the IBHOF museum.

His exclusion from a shrine basically created to pay homage to the legacy of his uncle Carmen, who was 85 when he died on November 7, 2012, continues to bother Backus, but at least he’s come to grips with the reality of the situation.

“I usually come in on Wednesday (the day before the first events in the four days of activities on Hall of Fame weekend) to see family and friends,” said Backus, since January 2006 the retired New York correctional department employee who now resides in Pageland, South Carolina. “I come in early because I can, and before the rush (of fight fans) comes in. When the rush does come in, of course I don’t get to see my family as much. But I stay over to the next Wednesday, when I leave to go back to South Carolina.”

There was no homecoming, of course, in June of this year because the IBHOF’s induction weekend was pushed back until June 10-13 of 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s highly unlikely Backus will finally join the enshrinees’ club since his name has never even appeared on the ballot in the Modern category.

“I’ve questioned it in the past,” Backus said of his failed quest to be considered for induction. “I’ve given it up now, and if that’s the way it’s going to be, I just have to let it go. I probably should have been inducted five or 10 years ago. But now … if it happens, it happens. I don’t hold any grudges. It is what it is.”

It also is this: in addition to his forever being linked to Napoles, that is even more so the case for him when it comes to his uncle Carmen, the “Upstate Onion Farmer,” who Backus describes as “our hero, the star of the family.”

Carmen Basilio, between rounds of his fight-of-the-year rematch with Sugar Ray Robinson, is the epitome of the blood-and-guts warrior.

“I was one of, I think, 42 nephews,” Backus said in 2013 of his famous fighting predecessor. “I’m the only crazy bastard that took up boxing. Everybody else went to school.”

During one of boxing’s golden eras, the 1950s and into the 1960s, Basilio, one of 10 children born to Italian immigrants, was a source of civic pride in his hometown of Canastota. And why shouldn’t he have been? He participated in The Ring’s Fight of the Year five consecutive years, from 1955 through 1959, a streak that is highly unlikely to be matched, much less broken.

It was with the idea of commemorating the achievements of Basilio, and to a somewhat lesser degree Backus, that Canastoa’s 4,000 or so citizens decided that something needed to be done to pay a visible, lasting tribute to those men and, through extension, to boxing itself.

Being constantly referred to as Basilio’s nephew at first was irksome to Backus, who understandably wanted to be recognized on his own merits as a fighter, but he soon came to understand that name recognition has its perks. He was prepared to call it quits on March 5, 1965, his 22nd birthday and the night of his third straight defeat, an eight-round decision to Rudy Richardson, when circumstances dictated that Backus stick with boxing a bit longer.

“If I performed really well, it was always noted that I was the nephew of the great Carmen Basilio,” Backus said. “But the more I looked at it, I realized it meant more publicity for me, more things for (the media) to write about. So eventually I was, like, `OK, I’ll go along with it.’

“Even Carmen laughed about it. He’d say, `I know, I know, they have to put it in there.’ He understood. I understood. What are you gonna do?’”

Backus was one of three possible optional challengers for Napoles, who was coming off a ninth-round stoppage of Pete Toro in a non-title bout in Madison Square Garden on October 5, 1970. As Backus recalled, it was he, Eddie Perkins and “I can’t remember the name of the third guy. I think he was from Hawaii or California, or maybe it was Michigan or Chicago.

Backus fell short of his famous uncle’s boxing accomplishments but put together a respectable pro career. Photo / Universal-Corbis-VCG-via-Getty

“As far as records go, mine at that time wasn’t really that impressive (29-10-4, 15 KOs), even though I’d beaten some good fighters. I was working construction in the early part of my career so I was taking fights on short notice, when I wasn’t in great shape. I’d only be able to go hard for five or six rounds, then sort of glide through the last four. I lost a few decisions that way. Did Napoles (whose record then was 63-4, with 43 KOs) take me lightly? Oh, without a doubt.”

As it turned out, Napoles wasn’t only facing Backus in Syracuse. He was also going up against the font of information that uncle Carmen had provided his nephew.

“Carmen had a lot of words to say, and I listened to them because I knew what he had gone through, what he had accomplished,” Backus said. “He gave me the best way to get things done in the ring, to be the best that I could be.

“Now, as far as style, his was a lot different from mine, even though we were both infighters. I stood back a little bit more and looked for the jab. Carmen always wanted to dig to the body and throw as many punches as he could. He made me more of a combination puncher. I think I hit with a little more power, but he threw punches in bunches. It makes a difference.”

So pleased was Basilio by Backus’ bravura performance that he was moved to say that “Billy winning the world title is the best thing ever to happen in my life, even better than me winning the world title.”

Recognition as a world champion and lavish words of praise from his legendary uncle had to suffice for Backus, whose financial situation wasn’t improved at all by his watershed triumph. Although the promotion had a live gate of $46,000, of which Backus was contracted to receive 18%, he was paid nothing as the Syracuse Boxing Club was in the red, having to pay Napoles his guarantee of $62,000. Not only that, but Napoles was the only fighter on the card to receive a percentage from the closed circuit TV broadcasts to the west coast and Mexico.

Twenty-five years after winning his title, Backus was feted at a silver anniversary banquet in Syracuse, where Basilio said, “He was a dedicated fighter. I am proud of his championship fight and his entire career.”

During his speech to a sellout crowd, Backus said he had no regrets. Nor does he now. “Boxing has been good to me,” he said a quarter century ago of a career that spanned from 1962 to ’78. “I traveled the world, several times to Paris. I also fought in Berlin and halfway around the world in Australia.”