Dream Fights by the numbers: Mike Tyson vs. Joe Frazier

Editor’s Note: This feature originally appeared in the September 2018 issue of The Ring Magazine

Of all the dream matches that can be made among heavyweight champions, Tyson vs. Frazier is arguably among the most explosive – and potentially destructive. They shared physical similarities (they were billed as standing 5-foot-11½, but both were closer to 5-foot-10, while Frazier’s 73-inch reach was two inches longer than Tyson’s), possessed crippling shot-for-shot power (Tyson had 44 KOs in his 50 wins while Frazier boasted 27 knockouts in his 32 victories), and seemingly derived sadistic pleasure from their opponents’ pain (Frazier relished the punishment he inflicted on Muhammad Ali, while Tyson took pride in the whimpering he heard from one unfortunate foe, Tyrell Biggs, and during another post-fight interview said he wanted to drive a nose bone into Jesse Ferguson’s brain).

What self-respecting fan wouldn’t salivate at the prospect of “Smokin’ Joe” and “Iron Mike” exchanging bombs from bell to bell? The only question is how many bells those fans would get to hear.

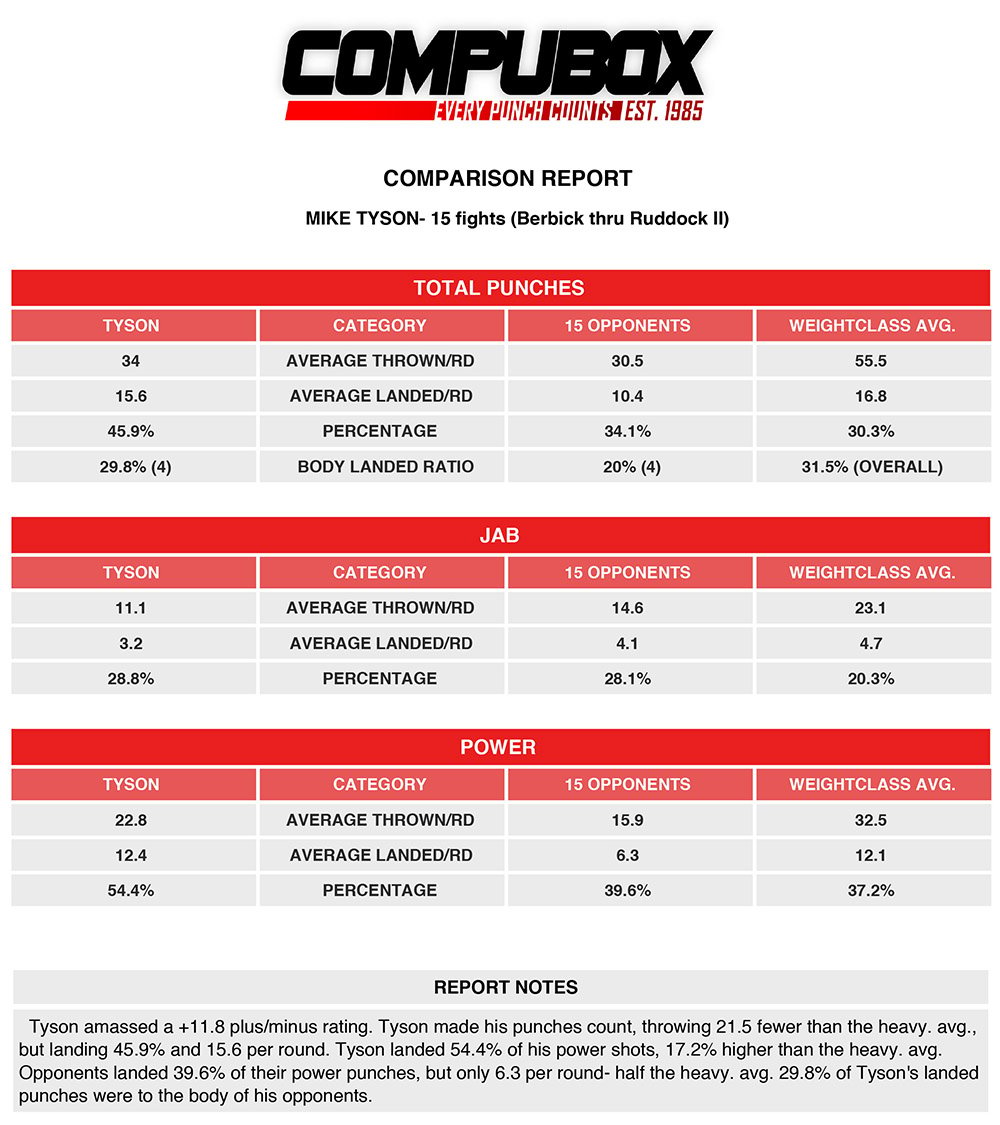

CompuBox has data for 18 Frazier fights as well as 26 of Tyson’s, but because this article examines prime vs. prime, it will assess figures involving fights waged during their best years. For Frazier, the informational pool will be his 11 CompuBox-tracked fights between July 1967 (George Chuvalo, his last prominent pre-title foe) and January 1973 (George Foreman, his first defeat despite being a betting favorite). (Two of Frazier’s fights during this period, his third-round KO of Marion Connor and second-round stoppage of Tony Doyle, were not counted because no complete footage of those bouts is available.) Tyson’s stats will be drawn from his 15 fights between November 1986 (Trevor Berbick, his first major title victory) and June 1991 (the Donovan “Razor” Ruddock rematch, his last pre-prison fight).

The following are several factors that may influence the outcome.

Frazier in “Eye-to-Eye” fights:

Because Frazier campaigned before supersized heavyweights became commonplace, he was able to fight similarly sized aggressors, such as the 6-foot Jerry Quarry (twice, though their second fight was after Frazier’s “prime” and won’t be used in this sample), the 6-foot Chuvalo (one of the toughest fighters ever to live), the 5-foot-10½ Oscar Bonavena (twice, though their first fight was before the “prime” boundary and won’t be used here) and the 5-foot-11 Ron Stander. Frazier was at his beastly best in these fights; despite throwing fewer punches per round (a combined 61.9 for Frazier versus 70.9 for the opponents), Frazier landed 14.8 more total punches per round (32.3 vs. 17.5) and connected with stunning precision (52.2% overall, 33.6% jabs, 57% power). Frazier’s jab success in these fights (he landed 4.2 of his 12.5 jabs per round) is striking given that his jab is overlooked when assessing his greatness. Also, his defensive numbers are much better than one might think, as he was hit by 24.7% of his foes’ overall punches, 8% of their jabs and 33.7% of their power shots, all below the respective division norms of 33.8%, 25.4% and 40.9%). That’s because the overarching image of Frazier is shaped by his fights against Ali and Foreman, the only two men to have beaten him. While “Big George” bludgeoned Frazier and Ali stabbed his eyes shut with his stiletto jabs and pinpoint crosses, Frazier’s bob-and-weave fared much better against everyone else.

The first Quarry fight – THE RING’s 1969 Fight of the Year – perfectly illustrated the folly of swapping punches with a peak Frazier. Although they traded at a nearly even rate (65 total punch attempts per round for Frazier, 64.6 for Quarry), it was Frazier’s shift into overdrive starting in Round 3 that left Quarry choking on his opponent’s dust and, eventually, on his own blood. In Rounds 3 through 7, Frazier outlanded Quarry 213-94 overall and 169-86 power, with the gaps most frightening in Rounds 6 and 7 (93-26 overall, 74-24 power). Even worse for Quarry: He injured his right hand during the fight and sustained a horribly cut cheek. But, Quarry being Quarry, he fought on – to his peril. Frazier averaged a mind-boggling 40.4 connects per round (nearly triple the 15.1 heavyweight average) in the 1969 fight, and while Frazier absorbed a high percentage of Quarry’s blows (37.8% overall, 13% jabs, 43.8% power), he compensated by landing virtually at will (62.2% overall, 53.4% jabs, 64.4% power). Frazier’s vaunted body attack was in full force as it accounted for 104 of his 234 power connects (44.4%, which is in line with his 10-fight average of 39.9%), while Quarry was a more-than-respectable 85 of 160 (53.1%). Even Frazier’s jab was landing with authority as he averaged seven connects per round. The final numbers perfectly illustrated the pain and chaos inflicted over seven rounds: 283-171 overall, 49-11 jabs and 234-160 power.

Chuvalo attempted more punches overall than Frazier (92.6 per round to Frazier’s 82.5) but Frazier’s rolling guard and sticky punches contributed to him landing more often (137-85 overall, 14-12 jabs, 123-73 power) and much more accurately (53.7%-29.7% overall, 38.9%-15.4% jabs, 56.2%-35.1% power). Frazier’s blows broke an orbital bone and led to the fight being stopped early in Round 4.

Stander, who was stopped in four rounds, also threw more punches than Frazier (79 to 61 per round), but it did him no good as Frazier led 54.6%-25.9% in overall connects and 59.3%-30.1% power, as well as 133-82 overall and 109-82 power. Worse yet, Stander failed to land any of his 44 jabs while Frazier went an impressive 24 of 60 (40%).

As for Bonavena, he couldn’t duplicate the success he’d enjoyed against a pre-prime Frazier in 1966. In that bout, Bonavena scored two first-round knockdowns en route to a split decision loss over 10 rounds. When they met again in December 1968 for Frazier’s New York State Athletic Commission heavyweight title, Frazier was utterly dominant. In winning a lopsided 15-round decision, Frazier outlanded “Ringo” 417-187 overall and 378-151 power while also creating yawning accuracy gaps of 46.2%-17.4% overall, 20.7%-6.7% jabs and 52.9%-28.3% power. Also, Frazier led 176-58 in total body connects.

The moral of the story: If you’re a short fighter who goes for it, you’re in trouble against Frazier.

Tyson vs. Aggressors:

Unlike Frazier, most of Tyson’s better opponents were taller than he was, but some were brave enough (or foolish enough) to trade with him – or at least not run away from him. Trevor Berbick tried his best to keep his WBC belt but Tyson, who said he was punching with “murderous intentions,” was a force of nature as he outlanded Berbick 77-16 overall (31-4 jabs and 46-12 power), recorded massive accuracy gaps (56.2%-37.2% overall, 44.3%-23.5% jabs, 68.7%-46.2% power) and famously scored three knockdowns with his final punch, a short hook to the temple near the end of Round 2. Like Frazier, Tyson’s jab was immensely effective; he averaged 35 attempts and 15.5 connects per round against Berbick, the latter figure being nearly triple the 5.2 heavyweight average while limiting Berbick (never a great jabber) to a puny 8.5 attempts and 2.0 connects per round. A byproduct of Tyson’s attack was that while he averaged a robust 68.5 punches per round, he limited Berbick to 21.5, less than half the 44.7 division norm.

Michael Spinks foolishly eschewed his tricky mobility in favor of proving his manhood – or perhaps working out his fear. A lathered-up Tyson was primed for the biggest stage of his fistic life and he delivered arguably the most destructive 91 seconds of his career. The fight’s brevity produced tiny raw numbers (8-2 in terms of overall connects and in landed power shots – both men threw one jab that missed), but the carnage was unforgettable.

The fantastically sculpted but muscle-bound Frank Bruno had little choice but to trade with Tyson in two fights due to his limited mobility and, as a result, he absorbed the full force of Tyson’s talents. Bruno managed to briefly stun and outland Tyson 14-13 overall and 13-12 power in Round 1 of the first fight (the only one included in this statistical study), but from then on, Tyson asserted his superiority. In Rounds 3-5, he led 62-15 overall and 55-14 power, and for the fight (which ended at 2:55 of the fifth) he prevailed 89-37 overall and 81-33 power, landing 44.1% overall and 50.3% power to Bruno’s 21.8% and 32.4% respectively. Like the Spinks fight (and unlike the Berbick bout), the jab was a non-entity as Tyson went 8 of 41 (19.5%) against Bruno.

Given these numbers, is it any wonder why the rest of Tyson’s opponents tried to keep him at arm’s length? Many ultimately failed in their quest, but James “Buster” Douglas found the right balance between science and aggression against an admittedly unfocused and ill-conditioned Tyson. Averaging 46.6 punches per round (including an extraordinary 13.5 landed jabs per round), Douglas limited Tyson to 22.6 punches per round while also shredding his defense, landing 52.2% overall, 52.7% jabs and 51.5% power. Despite his depleted state, Tyson still managed to land 47.2% overall, 30.3% jabs and 56.5% power, but the activity gap resulted in Douglas’ leads of 230-101 connects overall, 128-23 jabs and 102-78 power. Douglas’ success wouldn’t help Frazier much against Tyson, though, because he sported a completely different physique as well as a diametrically opposed style.

Following the image-shattering loss to Douglas, some fighters – particularly Donovan “Razor” Ruddock – opted to rumble with Tyson. While Ruddock repeatedly landed his patented “Smash” (the name for his devastating left uppercut-hook hybrid punch), Tyson was the better fighter in both contests. In fight one, Tyson led the aggressive Ruddock 125-68 overall, 19-6 jabs and 106-62 power as well as 45.9%-39% overall, 26%-14.3% jabs and 52.8%-47.1% power. In the rematch, however, Ruddock fought more on the retreat thanks to a knockdown (and a broken jaw) in Round 2, followed by another in Round 4. Despite the low output by both (38.1 total punch attempts per round for Tyson, 28.8 for Ruddock), the punishment dished out was plentiful (190-116 overall and 178-95 power shots landed, percentage gaps favoring Tyson of 41.6%-33.6% overall and 52.8%-43.6% power).

Points of separation:

When one compares the prime performances of Tyson and Frazier, Frazier wins most of the statistical arguments. He was the more active combatant (53.6 punches per round to Tyson’s 34) whose punch distribution was more destructive (81.7% of Frazier’s total punch attempts and 89.8% of his overall connects were power shots to Tyson’s 67.1% and 79.5% respectively). Also, Frazier was more accurate overall (51.1% to 45.9%), attempted and connected with more power punches per round (43.8 attempts and 24.6 connects per round to Tyson’s 22.8 attempts and 12.4 connects per round) and was the more precise power-hitter (56.2% vs. 54.4% landed). Somewhat surprisingly, given their reputations, Frazier was also the harder fighter to hit, as his prime opponents landed 27.7% overall, 16% jabs and 35.8% power while Tyson’s foes connected on 34.1% overall, 28.1% jabs and 39.6% power. It can be argued that Tyson’s opponents from top to bottom were better than Frazier’s, which may skew the numbers. In fact, the only statistical argument Tyson wins is in jabs (11.1 attempts and 3.2 connects per round to Frazier’s 9.8 attempts and 2.8 connects per round), but even then, Frazier trails Tyson by just 0.2%.

A major difference favoring “Iron Mike” was his iron chin. Expanding this examination to the entirety of their careers, Frazier was dropped twice by Bonavena in their first fight in 1966, eight times by Foreman in their two fights and stunned by the relatively light-hitting Muhammad Ali in two of their three bouts (though not in fight one, when both were closest to their respective primes). Meanwhile, Tyson’s first knockdown – in his 38th fight – was the result of a neck-wrenching uppercut from Douglas, and while he was briefly buzzed by Tony Tucker and Bruno (first fight) in Round 1, he quickly shook off the blows and proceeded to dominate. It wasn’t until later in his career that Tyson’s chin betrayed him as Evander Holyfield (twice), Lennox Lewis, Danny Williams and Kevin McBride felled the fading great.

An even bigger – and perhaps pivotal – difference is that Frazier was a notoriously slow starter while Tyson was blowtorch hot from the start. At the same time, however, once Frazier warmed to his task, he was difficult to dislodge. Tyson, once the flame waned, was more vulnerable.

Prediction:

We know the prime Frazier and Tyson can dish it out, but, by and large, Tyson at his best had a cast-iron jaw that stood up to the most powerful of fists. He also owned quicker hands, flashier head movement and better combination punching. Also, while Frazier had arguably history’s greatest left hook, his right hand was ordinary by comparison. Conversely, not only was Tyson a genuine two-fisted puncher, he also could deliver his power from both the orthodox and southpaw stances. Finally, Tyson’s emotional shortcomings, which often manifested themselves in bizarre ways, didn’t surface until later in his career.

So, with all of these advantages in his pocket, Tyson should be an easy winner, right?

Not necessarily.

Here’s why: While Frazier twice fell to Foreman, Foreman possessed a tremendous size advantage to go with his gargantuan punch. That, in addition to “Big George’s” tremendous ability to rev his engine quickly, was far too much for the slow-starting Frazier to overcome. However, against bombers closer to his own size – like Quarry, Chuvalo and Bonavena – Frazier was able to overcome early storms, find his groove and come out the winner in each one of their five meetings. Although Tyson will carry more weight and will sport a chiseled physique, he’s not the giant that Foreman was, so one can surmise that Frazier has a decent chance of shaking off Tyson’s jet-fueled, Round 1 attack.

Should Frazier get past the first two or three rounds, the onus will shift to Tyson, who must prove that he can prevail in a hard, tough fight against someone who is offering robust resistance. While he scored an eighth-round knockdown against Douglas after being outboxed for most of the fight up to that point, he couldn’t summon a second surge when Douglas regained his feet and resumed his attack. The proof: Douglas outlanded Tyson 52-14 overall and 32-14 power in the ninth and 10th rounds.

Tyson will be the one who will come out smokin’, and he may even register an early knockdown, because Frazier may be shocked by the speed and force of “Iron Mike’s” fists. But Frazier, fortified by his extraordinary toughness and his ferocious competitive drive, will shake off the early punishment and become what he has always been: boxing’s ultimate heart monitor. As he acclimates to Tyson’s quick and powerful combinations, Frazier will do a better job of avoiding the fire with his bob-and-weave tactics and then, after sufficiently warming up, will begin to unload his own thunder. Round after round, Frazier will methodically work over Tyson’s ribs while mixing in a heavy dose of hooks to the jaw. Slowly but surely, the effects of Frazier’s work will sap Tyson’s gas tank – and perhaps his will to carry on – and once Frazier spots that “give” in Tyson, it will be game over. Frazier by 12th-round TKO.

THE FOUR KINGS SPECIAL

available on pre-order now at

THE RING SHOP (Click Here)