The Buddy McGirt Chronicles pt. 2: Another title, a lawsuit, and dinner with John Gotti

Read The Buddy McGirt Chronicles pt. 1, here.

The loss to Meldrick Taylor was a hard one to live down. Had Buddy McGirt gotten past Taylor, a fight with Julio Cesar Chavez was likely for January of 1989. Chavez was one of the sport’s most popular fighters, and facing him could have made McGirt one of the best known fighters on the planet. Instead, McGirt was back at the Felt Forum in New York, stopping Manuel De Leon in six rounds, and Taylor was the one heading towards the Chavez opportunity.

“It was just in talks, there was nothing definite,” McGirt (73-6-1, 48 knockouts) said of the Chavez fight. “I think I still would have continued doing what I was doing, I was gonna move up anyway. So after I would have beat Chavez I would have moved up to 147, which I wanted to do after I won the 140-pound title.”

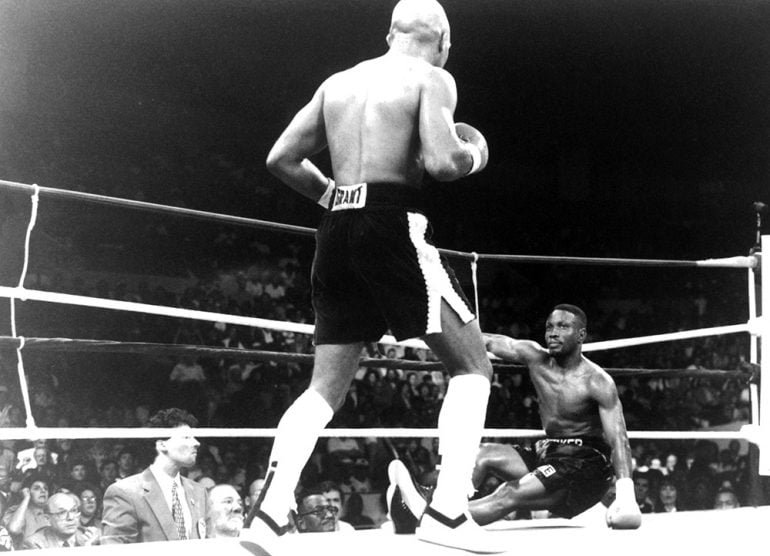

The De Leon fight began a winning streak that would take him into the part of his career he’d best be known for. There were some who didn’t think McGirt could be strong enough at welterweight, but McGirt says he felt much better there. There was the memorable war with Tony Baltazar in July of 1989, when a left hook put McGirt on the canvas in round two, only for McGirt to rally back behind his classic boxing ability, then a month later McGirt stood up to the body punching assault of Scotland’s Gary Jacobs for another decision win. Any questions about whether McGirt had brought his punch up with him were answered by March of 1990, when one overhand right ala Tim Witherspoon dropped Tommy Ayers, leading to a second round stoppage.

Forgotten Classic: Buddy McGirt gets dropped in round 2 by Tony Baltazar in their 1989 non-title fight, before coming back to outbox Baltazar and win a decision. McGirt says after that Baltazar was the hardest puncher he had fought pic.twitter.com/ciwSRa16Ox

— Ryan Songalia (@ryansongalia) May 29, 2019

McGirt went under the knife following his unanimous decision win over Jose Leonardo Bermudez in July of 1990 to repair torn tendons in his left bicep, but was back in the ring at the beginning of the following year.

After sixteen straight wins, McGirt received a shot at the WBC welterweight title fight in November of 1991 at The Mirage in Las Vegas. Brown entered the fight with a 34-1 record, having held a title at 147 pounds for three years, and had shown his power and killer instinct by finishing fellow beltholder (and friend) Maurice Blocker in his previous outing.

Had Brown won this fight, a showdown with Chavez could have been next. This time, it was McGirt’s turn to spoil someone’s shot at the legend from Culiacan, Mexico.

“I just had a thing in my mind going into that fight, I went into a zone in that dressing room that it took me a week to get out of,” said McGirt.

“I knew that this was a do or die situation as far as my career was concerned, coming back off the injury that I had previous to that and there was a lot of doubters. I was a 10-1 underdog, but in my heart I knew, if I never win another fight in my life, I’m winning this one tonight.”

McGirt’s plan was to start fast against the slow-starting Brown, and step up his own attack as Brown attempted to build tempo. He fought Brown inside, he boxed him from the outside, and took steps back to counter effectively. Then, in round ten, Brown walked into one counter too many and was dropped by a flurry that was punctuated by a hook. McGirt had the belt strapped around his waist before the decision was even announced. He was now a two-division world champion.

Earlier in the year, Taylor had also moved up in weight and defeated Aaron Davis to win the WBA welterweight title. Shortly after McGirt’s win, talks began for a unification rematch at 147 pounds, and despite McGirt’s team being offered a career-high payday, talks blew up over money.

“My manager blew the Meldrick Taylor fight. He turned it down, he wanted an extra $200,000, and being that they wouldn’t give it to him he turned it down. They offered us $1.8 million, he wanted $2 million,” said McGirt.

Having the belt normally would be cause for a fighter to slow his schedule down, but that wasn’t McGirt’s style. After a few months off, McGirt faced Delfino Marin in a non-title fight in May of 1992, then went to Italy to outbrawl former 140-pound titleholder (and Olympic gold medalist) Patrizio Oliva for his first title defense, then was back in the ring less than two months later for another non-title fight with Oscar Ponce.

“Because I love the sport, number one, and I had bills to pay,” said McGirt, when asked why he fought so frequently. “I love the thought of going to training camp. When I was champion the second time, I had two non-title fights. What guys do that today?”

Buddy McGirt’s best performance was against Simon Brown in 1991, when he defused the heavy puncher to win a one-sided decision for the WBC welterweight title. Mixed boxing and in-fighting to take the belt in Las Vegas pic.twitter.com/yTuSpMmPjv

— Ryan Songalia (@ryansongalia) May 28, 2019

McGirt’s next title defense, a mandatory against Genaro Leon at the renamed Paramount Theatre, was set for January of 1993 on USA Tuesday Night Fights. All he had to do was get through this and a fight with Pernell Whitaker – and his first $1 million purse – would be next.

Towards the end of training camp, around Christmas time, McGirt throws a left uppercut in sparring and feels a pain he had never felt before.

“So Al took me to a doctor, doctor did an x-ray, told me it was tendonitis. I’m like ‘doc, I’ve had tendonitis, this s__t hurts.’ For a week all I did was shadowbox, I didn’t do nothing else for a week. They sent me to another doctor, an orthopedic doctor, he says it’s tendonitis, don’t worry it’ll be fine, we’re gonna give you a shot. For the last ten days or two weeks I couldn’t do nothing else,” said McGirt.

“I said ‘Al, why don’t we just give this guy some step aside money, so I can really get my shoulder ready for the Whitaker fight.’ He goes ‘they won’t take it.’ I said ‘if you offer the motherf__ker enough money they’ll take it.’”

McGirt gets through the fight with the rugged Leon throwing only 1-2 combinations without any use of his left hook to win a unanimous decision. With the Whitaker fight set for two months later at Madison Square Garden, McGirt is sent to a rehab facility to work on his shoulder, but even with treatment he’s unable to throw his left hook, an important weapon in his arsenal.

“The night we’re going to the weigh-in, we were in the limo, I’ll never forget it, we just paid the toll at the Lincoln Tunnel, and Al looks at me and says ‘if you want to pull out you can.’ I looked at him and said ‘you motherf__ker, you knew all along that my s__t was f__ked up and you’re gonna ask me this now an hour before the weigh-in?’”

Traditionally, McGirt had done well against southpaws, going 6-0 in prior fights against lefties before facing Whitaker, who had been undisputed champion previously at 135 pounds before moving up to 140 to win another belt. But this time, McGirt didn’t have use of his left hook, which could have kept Whitaker from circling to his right and made his right hand more effective.

“I would have won the first fight without a doubt,” said McGirt, when asked what would have happened had he not been injured, adding that he saw openings for the hook “all the time” but just couldn’t pull the trigger. Whitaker won the decision, and McGirt went back to get another opinion on his shoulder.

“We go to a doctor in New York, Doctor David Altchek, he looked at the old MRIs and said you have a torn rotator cuff. He does the surgery, tells me afterwards that my career is over or it would take me a year before I could come back. As this is going on I’m hearing stories that everyone knew but me so I’m like motherf__kers sold me out,” said McGirt.

McGirt says he only threw a serious hook twice more in the remainder of his career “but it wasn’t the same.”

As McGirt gets the wheels moving on a malpractice lawsuit, he’s also determined to prove the doctors wrong by returning to the ring. He does so after eight months, defeating Nick Rupa by decision, and quickly runs his winning streak to five by fighting once every other month. After winning a split decision over Pat Coleman in the Catskills, he gets news that brings him to tears.

“After the Pat Coleman fight they come to the dressing room and tell me you got the rematch with Whitaker. I started crying and my wife is like ‘what’s wrong?’ I said, ‘I did what they said I couldn’t do.’ She said ‘what are you gonna do now?’ I said ‘I don’t want to fight no more…I gotta fight, I don’t want to but I have to. How else am I gonna make a living?’”

McGirt heads to Whitaker’s hometown of Norfolk, Virginia in October of 1994, and despite knocking Whitaker down on a right hand in round two, is thoroughly outfought. At age 30, what could McGirt have done differently to change the outcome? “Not show up,” said McGirt.

The malpractice lawsuit is finally filed in United States District Court on February 24, 1995, and depositions begin.

“I gave mine, they told me my memory was phenomenal. And then my lawyer said to me, if your manager comes in next week and tells the truth, you’re gonna be about $20-30 million dollars richer because we got these motherf__kers,” said McGirt. All seemed on track, until the wheels came off.

“[Certo] went into the deposition and he went against me. I couldn’t believe it. The lawyer called me and said ‘Buddy I thought he was your friend. He buried you.’” It wasn’t until a decade later, when they met again at the Antonio Tarver-Roy Jones III fight in Tampa in 2005, that McGirt confronts Certo about why he didn’t corroborate his version of the story. The answer he received wasn’t the answer he was looking for.

“I hadn’t spoken to him in all this time, we were out by the pool and he came out and he said ‘kid I know you’re mad at me.’ I said ‘Al, man, you cost me a lot of money, my career, of course I’m gonna be f__king mad. You tell me you love me like a son and you do this?’ Do you know what his response to me was?

“‘I had to go against you because if not the mob was gonna kill me,'” McGirt says Certo told him.

“I said ‘are you out of your f__king mind?’ He said, ‘I’m telling you kid, the mob was gonna kill us.’

“Over a lawsuit? Why you think doctors got insurance?”

McGirt just walked away.

“I’m like ‘Man, this is bulls__t. You didn’t want me to get that money, that’s what it was in a nutshell,'” said McGirt.

Under typical circumstances, such an explanation would seem taken out of a Hollywood movie, but neither McGirt nor Certo were totally unacquainted with the Mafia.

McGirt’s co-manager Stuart Weiner gave him a call one night and tells McGirt to meet him in Manhattan for dinner with a friend. McGirt brings along his one-year-old daughter, and when he gets to the restaurant, sees John Gotti, the head of the Gambino mafia family. With him is a man he used to see every morning at Gleason’s Gym, and who had also trained with Hector Roca, but whose name he never got. That man was known by the name Sammy “The Bull” Gravano.

A month after the first Whitaker fight, Gravano, the Gambino underboss who had become a government witness in the racketeering and murder trial against Gotti, testified before the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, alleging that McGirt’s managers Certo and Weiner were mob connected and that the Gambino family was profiting off McGirt’s career. Gravano alleged that the mafia was no longer interested in fixing fights and betting on the outcomes; their new hustle was to take cuts from the purses of boxers under their control.

Weiner plead the Fifth Amendment when asked if he was affiliated with the Gambino family, but Certo wasn’t having any of it, offering a “crude gesture” to Gravano, according to the New York Times. “Let him and me take a lie detector and see who’s lying in front of all you people. I don’t know him. I’ve never met this guy in my life. This is the first I’ve laid eyes on him. He doesn’t know boxing,” Certo said. McGirt backed up Certo’s claims.

“Sammy the Bull tried to say that John Gotti controlled my career through Al Certo. Bulls__t, John Gotti hated Al Certo. Al Certo was with another family in New Jersey. The truth to the story is, my manager Stewey was good friends with John Gotti. Stewey has a Jewish last name, God rest his soul. So who are the feds gonna go after, the guy with the Jewish last name or the Italian last name? So when Al Certo says Sammy the Bull is a lying c__ksucker, he was telling the truth. Because Al had nothing to do with John Gotti, John Gotti had nothing to do with my career, he was just a friend and a fan,” said McGirt.

It got to the point that McGirt was brought to a small room and interrogated by the FBI.

“I felt like I was in the 1950s, I’m looking around and there’s all these mobsters on the wall and they said ‘is there anybody who looks familiar?’ And I go, ‘are you guys serious right now? Half of these guys are dead.’”

Brought before the Senate, McGirt answered questions incredulously.

Why did you go to dinner with them? “I was hungry, they invited me.”

What did you learn from being around them? “They eat good, they tip good. They brought me to the best restaurants, we ate good, we talked boxing, bullshitted, I left.”

“Not one time did they go, ‘hey Buddy you owe us this.’ Gotti had more money than I could dream of, so what the hell was he gonna ask from me?”

McGirt had been spotted at Gotti’s trial, which ultimately resulted in him being sentenced to life imprisonment without parole, but McGirt maintains his true motivation was to watch Gotti’s lawyer Bruce Cutler in action.

“He was the Denzel Washington of being a lawyer. Let me ask you a question, how many guys you know go on trial and they tell you who you can and cannot pick as a lawyer? They told John Gotti that he cannot represent you,” said McGirt, referring to the ruling that Cutler could not serve as counsel for Gotti, because he could have been called as a witness.

Even still, McGirt could feel the stares when he walked into restaurants from people who had seen his name tied in with the most famous mobster since Al Capone.

“I’m like, why the f__k are ya’ll staring at me? They’re like Buddy, you’re in the mob? I’m like, let me ask you guys a question man, how many black people do you see in the mob? Even on TV? They said none. I said, ‘then why are you f__king with me, man?’”

The memory of those hearings have largely faded, but one footnote in pop culture has immortalized it: In the television show The Sopranos, a photo of McGirt hangs on the wall behind Tony Soprano’s desk at his office, a wink and a nod to those headlines.

“I never watched the Sopranos, and everybody used to call me and go ‘hey Buddy, your picture’s hanging up on The Sopranos.’ I’d go yeah? Then tell those motherf__kers to cut me a check,” said McGirt.

Buddy McGirt at his most vicious: Knockouts of John Sinegal, Tommy Ayers, Sergio Aguirre, Ralph Twinning, Charles Baez, Joe Gatti & Frank Montgomery pic.twitter.com/wgVAiOwVdH

— Ryan Songalia (@ryansongalia) May 29, 2019

McGirt and Certo split up after his 1995 TKO loss to Andrew Council, which was fought at junior middleweight. McGirt announced his retirement but came back a year later with trainer Dickie Wood, who was based out of Colorado Springs, Colorado. After six straight wins in 1996, McGirt was matched with his former sparring partner Darren Maciunski, who had Certo in his corner. McGirt appeared listless, and after losing a decision, Certo hugged the fighter he would most closely be associated with.

“Al said he did it to show me I didn’t have it anymore, and I’m like ‘you got a good point there because if I wasn’t gonna beat that motherf__ker, then I wasn’t gonna beat nobody,’” said McGirt.

As conflicted as his memories of Certo are, he remembers him as someone who stuck up with him many times over. “Al was a crazy ass manager but I learned a lot from him because he exposed a lot of people. Al would fight, right, wrong, better or indifferent,” said McGirt.

The Maciunski fight would be the last for McGirt as a professional, but there was one fight that he accepted afterwards that never took place.

Shortly after, McGirt got a call to face Shawn O’Sullivan, a 1984 Olympic silver medalist from Toronto whose career never took off past the domestic level as a pro. The purse was $100,000 to fight him in Canada, too large a payday for McGirt to turn down. As he’s preparing to leave to Colorado Springs, McGirt’s wife gives him some straight talk.

“She goes, ‘I want you to know one thing, you’re being selfish right now. You’ve got a family and you had to take this one more fight.’ I go ‘baby, it’s $100,000.’ She goes, ‘I don’t care if it’s $200,000, you’re not thinking about your family,’” remembers McGirt.

McGirt arrives in camp, and the first morning he does his run and workout without issues. The second day, he hits the snooze button repeatedly on his alarm clock, and when he finally arrives at the park to run around the lake, he sees the other boxers finishing up. Typically by 8 o’clock he’s already done, showered and having breakfast, but on this day he was just starting at 8. McGirt makes up his mind that it truly is over, and returns to his apartment to pack his belongings.

“I called my wife, I said ‘I’m coming home…you were right,’” said McGirt.

“I gotta tell you this, that was the longest plane ride of my life. On the plane I’m saying to myself, how am I gonna make a living? What am I gonna do with my life? I got a family, I got a mortgage, I got car payments. What am I gonna do? So imagine five hours of stressing over that s__t on the plane? It’s like, man, you’re just sitting there and the closer I got to home I say I gotta face my family now, I just left 100k to come home to try to figure this s__t out.”

McGirt eventually figured out what he’d do with his life, becoming one of the most celebrated trainers so far this century. He won his first world title as a trainer in March of 2001 when he stepped into Byron Mitchell’s corner on six days’ notice and helped guide him to a twelfth round TKO win over Manny Siaca to win the WBA super middleweight title. The following year he was honored by the Boxing Writers Association of America as Trainer of the Year and helped bring Arturo Gatti, Antonio Tarver, Vernon Forrest, and more recently, Sergey Kovalev to championship glory.

McGirt had long been based in Vero Beach, Florida, but now trains fighters in Northridge, California, part of the San Fernando Valley region outside of Los Angeles. He says he can forget what he did the day before, but his memories of his career – and the hard lessons he picked up along the way – remain as vivid as ever.

“It made me understand that a lot of people who claim to be your friend and have your back are full of s__t. I heard an old guy say one day, as long as the band’s playing everyone’s dancing. But as soon as another band comes along with a little bit of music, they’re gonna leave. That was the truth,” said McGirt.

Now, at least in his little nook in Canastota, the band will keep playing Buddy McGirt’s tune forever.

Ryan Songalia is a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and part of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Class of 2020. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @ryansongalia.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.