The Buddy McGirt Chronicles pt. 1: The long train ride out of Brentwood

The first day James “Buddy” McGirt started boxing, he fell in love with the sport. Two days later he realized that what he really wanted was to become a trainer, but figured he’d have to do a little bit of fighting to get some experience and credibility in the corner. It was the right call as McGirt went on to win two world titles, become one of the sport’s most celebrated trainers of this century, and, on June 9, will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame for his accomplishments in the ring.

Not bad for a guy who many still don’t even realize had been a boxer.

“I get some boxers that are surprised that I (was) a fighter. I could be training them for a week and (they) not realize who I am,” said McGirt, 55.

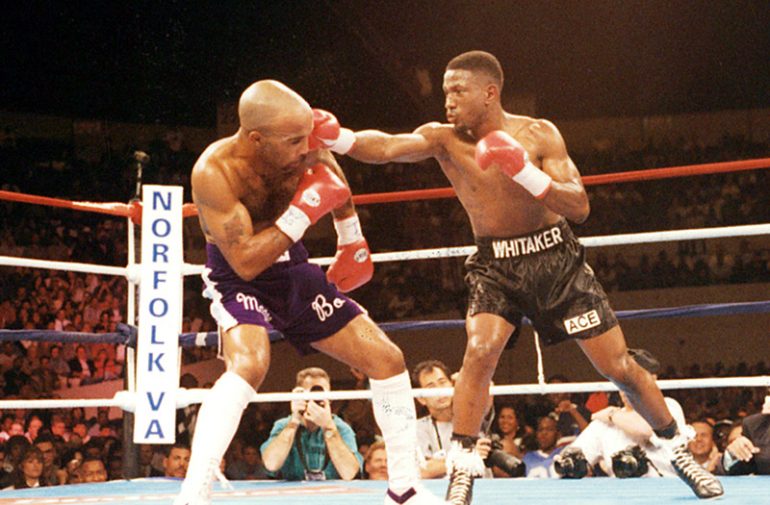

If you were a boxing fan in the 1980s and ’90s, you knew McGirt, not as the cool customer in the corner interjecting “baby” into every instruction for Arturo Gatti and Antonio Tarver, but as the smooth-boxing technician who won the IBF junior welterweight and WBC welterweight titles. He fought 80 times, an old-school amount even during his time, and was respected as a fighter’s fighter for his passion for the sport. It was that passion that made him emotional when he was informed he’d be joining the Class of 2019 alongside his contemporaries Donald Curry and Julian Jackson.

“When [IBHOF president] Ed Brophy called me and told me, I cried,” said McGirt. “I’m an old-school boxing guy and I watch all the old-school boxers to this day. To be honored in the same room as them, to me, it’s something that your grand kids and your great-grand kids, they’re gonna be able to say my great-great grandfather was a champion. But they’re also gonna get to say, my great-great grandfather is in the Hall of Fame.”

The journey to Canastota began on his twelfth birthday, January 17, 1976, the first day he was eligible to start boxing at the Brentwood Recreation Center in his hometown on Long Island. It was also the first day the program began accepting kids, and after Catholic religious instruction, he went down and strapped on a pair of gloves for the first time.

“I had tried other sports but it just wasn’t for me. Football was OK until the winter. I would not stand out there in the freaking cold to tackle some-fucking-body, that wasn’t happening for me. So I used to always go to the rec center because they had basketball over there,” said McGirt.

He had his first amateur fight a month later, fighting another youngster named Ricky Randazzo from nearby Centereach to a draw.

His amateur career “wasn’t anything spectacular,” he says, consisting of 53 wins, 8 losses and that draw, and winning a Spanish Golden Gloves title.

The signature look he carried through his career – blue trunks with socks pulled up to his knees – came from a practical reason. “I used to have these scars on my legs when I was a kid, I was a little embarrassed by them so I’d always wear high socks. It had to be two pair on each foot and up to my knees,” said McGirt. And the trunks? “Blue was my favorite color so I just went with the blue and white.”

McGirt’s first pro fight was set for March 2, 1982 at Embassy Hall in North Bergen, N.J. The fight was on a Tuesday; he got the call the previous Wednesday and jumped at the $200 purse. “I’m like ‘shit that’s a lot of money.’ I said I’ll be ready and I trained the rest of the week,” said McGirt. At the weigh-in he met Al Certo, who managed Lamont Haithcoach, and McGirt figures Certo expected him to be knocked out in three rounds. Instead the fight went to a draw, and two days later McGirt was standing in Certo’s tailor shop in Secaucus, N.J., accompanied by his managers, Stuart Weiner and his brother-in-law Lou Caravella, looking to add Certo’s services.

“[Caravella] goes to me and says I want you to train with this old man Dom Amoroso. I’m like why, he said because all of his guys won except the guy you fought,” said McGirt. Amaroso, a tough 1940s lightweight who once traded punches with Sandy Saddler, said he’d train him, but wondered how would he would get from Long Island to the gym in Hoboken, N.J.

Weiner showed him how to catch the Long Island Railroad train to the PATH train at 33rd Street in Manhattan to Hoboken. McGirt was still in high school, but his shop teacher would allow him to leave early to catch the 12:27 train out of Brentwood so he could make the three-hour trip for vocational training of a different kind.

“I did that every day, six days a week for six years. Rain, sleet and snow,” said McGirt, who wouldn’t get home until about 9 at night. “I was number one in the world making that trip.”

When Amoroso and Certo moved operations to Bufano’s Gym in Jersey City, McGirt would have to walk even further. He’d cut through backstreets, and pass the Hudson County jailhouse, where prisoners would recognize him and shout out “Hey, Buddy McGirt!” When his son, James Jr. was born in November of 1982, his mother and sister would babysit as long as he promised to return straight away.

“Some days when I would get to Journal Square and it was raining, my trainer Dominick would be there. Some days he wasn’t, and he’d make me walk to the gym,” said McGirt, who laments some fighters nowadays complaining about having to drive 20 minutes to the gym.

“I had to do what I had to do, it all paid off but it was a motherf__ker. Nobody gave me s__t…it helped me be the person I am today.”

McGirt ran his record to 28-0-1 at venues around the Northeast before heading to Corpus Christi, Texas to face Frankie Warren, a shorter, but rough Tasmanian Devil of a brawler who was handled by Lou Duva, in July of 1986.

“I still have nightmares about that motherf__ker. He hit me on my thighs, on my hips, my ass cheeks. He hit me everywhere but the bottoms of my feet,” said McGirt, who ended up losing closely on two cards, and wide on the third. The margins didn’t matter to McGirt. He knew he had been defeated, but didn’t wallow in it.

“I understand why I lost while I’m in the dressing room. The hotel was about a mile from where the arena was, so I said to my manager, ‘I’m gonna walk back to my hotel, I want to walk by myself.’ He’s like ‘you gonna be OK?’ I said yeah ‘I’m gonna be alright,’” said McGirt.

By the time he reached the hotel, McGirt had figured out what he did wrong and put his first defeat behind him. Then he told Certo to get busy making his next fight. “It was something that I needed to help make me a better fighter,” McGirt said.

Two months later, McGirt was in the ring at New York’s Felt Forum with Saoul Mamby, a 17-year vet who had held a world title earlier in the decade and had fought just about everyone. McGirt looked to be overmatched on paper, and plenty of well-intentioned observers questioned the wisdom of the matchmaking. But McGirt showed a level of poise that he didn’t have two months earlier, outboxing the taller Mamby and wearing him down as the rounds progressed.

“I said to myself, I’m 22 years old, if I lose to a 39-year-old, I’m in the wrong business. That loss and the win over Saoul Mamby turned me around as a fighter. Made me a totally different fighter, made me a better fighter,” said McGirt.

Even in defeat, Mamby was able to make an impression on McGirt.

“I hit him with a right hand and I saw his legs [buckle] so I said to myself ‘I’m gonna be the first one to stop him.’ Then when I went in he hit me in the liver and I pissed on myself. And I got in the clinch, he said ‘slow your young ass down.’ And I said to myself ‘no problem.’ Because that motherf__king s__t hurt,” said McGirt.

McGirt won that fight by a wide decision, and seven more over the next two years before getting a second fight with Warren. The rematch would be back in Corpus Christi but the vacant IBF junior welterweight title was at stake. When the rematch was made, he thought back to a conversation with Warren’s trainer, Georgie Benton, after the first fight.

Buddy McGirt had an absolute war in his first world title fight, a 12th round TKO of Frankie Warren to win the IBF junior welterweight belt. The stoppage win avenged his only prior defeat and started him on his way to Canastota for the Hall of Fame #boxing pic.twitter.com/rB6nSNcVLa

— Ryan Songalia (@ryansongalia) December 6, 2018

“Me and Georgie were friends so Georgie told me what I did wrong. Then we get the rematch and Georgie looks at me at the weigh-in and I say ‘George, remember what you told me I did wrong? I corrected it.’ He said, ‘you motherf__ker.’”

His mother, who had a way of reading her son, also had a good feeling.

“When my mom got there, I said there’s no way in hell he’s gonna beat me. My mom always used to look at me before a fight, and if she said ‘son, be careful,’ I knew I was in trouble. If she said ‘you look alright, boy,’ I knew whoever I was fighting was in trouble. When she got to Texas she said ‘you know Frankie Warren called me last night. He said he gonna beat your motherf__king ass.’ I said ‘OK, not Sunday.’

The ring was small, or at least it felt that way, and McGirt knew he’d have to fight Warren and get his respect in addition to using his boxing skills. Midway through the fight, McGirt’s right hands began to puff up Warren’s left eye lid, and the ultra aggressive Warren stopped wading in so frequently.

“I hit him to the body and I heard him grunt and I said ‘I got yo ass now baby.’ At the end of the first round I hit him with a right hand and I hurt him, and I was like ‘oh baby.’” Two left hooks in the twelfth round punctuated an attack that sent Warren down. A follow-up attack convinced the referee to waive off the bout, earning McGirt his first world title.

With the win, McGirt fulfilled another dream, which was to become the first world champion from Long Island. His first defense came against another Long Islander, Howard Davis Jr. of Glen Cove in Nassau County. McGirt had been a sparring partner of Davis back in ’81, earning $500 a week to drive to Hempstead to box with the 1976 Olympic gold medalist. “He was so god damn fast it was scary,” McGirt remembers of those sessions. By ’87, Davis had lost his two previous world title attempts and was considered on the slide.

“That day was 100 degrees outside and the TV lights were hot so I said we gotta jump on him quick,” said McGirt. It was to be the last scheduled 15-round fight in America, but one right hand put Davis down for the count in the first round. “I honestly believe in my heart he could have gotten up because I’ve seen him get hit with much harder punches. When we came out I hit him with a body shot and he looked like he really didn’t want to be there for 15 rounds,” said McGirt.

His next defense, against 1984 Olympic gold medalist Meldrick Taylor, wasn’t as short a night. And this time, McGirt’s mom could sense something was wrong.

“She told me to come home, said you shouldn’t fight,” remembers McGirt.

“Stupid move number one, I shouldn’t have fought him. I had a serious ear infection, but I felt as a fighter and a champion I had to go out there and fight which was stupid of me.

“Going into the fight I knew I had to get him out of there early because I had no energy to go twelve rounds. I came out early trying to get him out of there, but he stood his ground and fought back and there wasn’t no gas station and I ran out of gas and I had to take that ass whooping for twelve rounds.”

The fight was stopped with a minute left, with Certo stepping through the ropes to preserve his fighter for another day. The year 1988 had started with McGirt winning a world title, and now ended with him losing it. If his story ended there he wouldn’t have even gotten on the Hall of Fame ballot. But it didn’t, and the ensuing years would bring bigger stages and controversies.

Part two of this story will be posted this week and will discuss his rise in weight, second world title reign, and his brush with the FBI.

Ryan Songalia is a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and part of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Class of 2020. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @ryansongalia.

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE