What we know about Al Haymon: Part I

THE RING’S Thomas Hauser in this special series sheds light on the powerful and mysterious boxing impresario Al Haymon and Premier Boxing Champions. First of five parts.

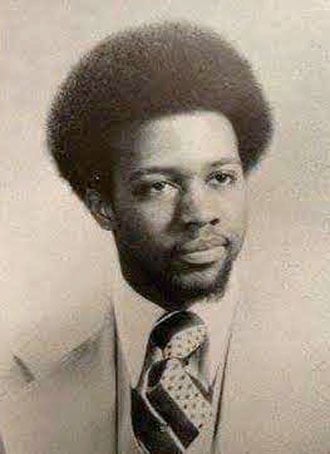

Al Haymon’s college graduation yearbook photo.

Shortly before a March 7, 2015, fight card in Las Vegas, Al Haymon did something that was totally out of character: He made a speech.

For months on end, the boxing community had buzzed with rumors: Haymon was amassing a war chest totaling hundreds of millions of dollars with the help of a venture capital fund in an effort to take over boxing … Haymon was signing hundreds of fighters to managerial and advisory contracts … Haymon was planning some sort of TV series … time-buys on multiple networks for an entity called Premier Boxing Champions (PBC) were confirmed.

March 7 marked the rollout of Haymon’s plan. NBC was televising the inaugural PBC offering, a fight card featuring Keith Thurman vs. Robert Guerrero and Adrien Broner vs. John Molina Jr.

Haymon had poured an enormous amount of money into TV production for the event. There was a huge floor set augmented by giant video screens. Twenty-seven cameras had been set up to capture the action from every possible angle under enhanced lighting.

Three iconic sports personalities formed the core of the NBC announcing team. Al Michaels would host the telecast from a glitzy in-arena set while Marv Albert handled blow-by-blow chores and Sugar Ray Leonard served as an expert analyst. Laila Ali, B.J. Flores, Kenny Rice and Steve Smoger were also in the mix.

Academy-Award winner Hans Zimmer, who’d written the signature music for “The Contender” (as well as screen scores for “The Lion King,” “Gladiator” and “The Dark Night Trilogy”) had composed special ring-walk music for the fighters.

Al Haymon was challenging the established order of the sport.

The final production meeting for the telecast was held in a meeting room at the MGM Grand.

“Al came in,” a member of the production team recalls. “There were 15 or 20 people there. He talked to us about the importance of boxing and his desire to revive interest in the sport. He said that everyone in the room should think of themselves as part of a team. He didn’t talk for long, only a couple of minutes. But he seemed sincere, like this really mattered to him.”

The NBC telecast averaged 3.37 million viewers, including 554,000 in the 18-to-34-year-old age group and 1.38 million in the 18-to-49 demographic. It was an encouraging start for an audacious plan. Backed by an estimated half-billion dollars in venture capital, Haymon was planning to revolutionize boxing.

Boxing people were excited or terrified depending on where their interests lay. To some, Haymon was a savior who would rejuvenate the sport and bring big fights back to “free” television on a regular basis. At the other end of the spectrum, the reaction ranged from denial to panic.

Haymon was creating a sense of inevitability. PBC would dominate boxing for years.

Except it hasn’t happened. And in all likelihood, it won’t happen.

Winston Churchill once said of Russia, “It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” The same words could be used to describe Al Haymon. This series is an attempt to shed some light on who he is and his journey through boxing. Dozens of people who know Haymon in one way or another were interviewed in conjunction with these articles. Some were willing to talk on the understanding that they could be quoted but not for attribution. A refrain often heard from others was, “I’d like to talk with you but I don’t want to get in trouble with Al.” Haymon, as is his custom, declined to be interviewed.

Al values his privacy … He doesn’t even like it when people tell nice stories about him.

Haymon was born on April 21, 1955, grew up in Cleveland and graduated from John Adams High School in 1973. Don King graduated from the same school in 1951. King recalls that Haymon’s father was a clergyman and that the promoter made occasional financial contributions to the latter’s church programs.

Haymon’s mother was an accountant. In a rare 1994 interview with Ebony Men, Al recalled, “She was a role model for me to follow because she had built a small business, an accounting practice. It was very successful, and it was hers.”

Haymon excelled in high school and attended Harvard College, where he was on the freshman basketball and varsity rifle teams. He majored in economics and was president of North House (one of 12 undergraduate residences). He was also active in the Afro-American Cultural Center. He promoted his first concert in 1976 during his junior year at Harvard.

Recounting that experience for Ebony Men, Haymon recalled, “I saw a concert that featured Minnie Riperton and Herb Hancock in 1975 between my sophomore and junior years. It seemed like something a person like myself, who had absolutely no money at the time and a lot of ideas, could venture into. So I started calling record companies, calling buildings around town, and trying to introduce myself as a promoter so I could learn about the business and try to find out what was going to be my strategy to enter it. My original plan was to go after acts that weren’t hotly pursued by much bigger competitors. I started with jazz artists. It was difficult because I didn’t have any money. I was basically hustling, pulling money together for these events, and learning at the same time.”

Haymon graduated from Harvard College in 1977. He took a year off from school and, with the help of his mother, continued to build his concert-promotion business. Then he returned to Harvard and, in 1980, graduated from Harvard Business School with a master’s degree in business administration.

In the years that followed, Haymon created more than a dozen companies to coordinate production, advertising, marketing and virtually every other facet of live concert promotion. He made his mark with national tours for superstars like Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, M.C. Hammer and Boyz II Men and co-promoted “Eddie Murphy Raw,” which was the highest-grossing comedy tour and centerpiece of the highest-grossing comedy film ever up until that time. In 1992, he told USA Today that during the previous year he’d promoted approximately 500 shows that had grossed $60 million.

Haymon is a complex man. People who’ve done business with him for years know next to nothing about his personal life (which is even more under the radar than his professional one).

“I have no idea how Al processes emotion,” one business associate says. “His tone of voice changes when he’s angry but that’s the only sign I’ve seen.”

By all accounts, Haymon is devoted to his mother, who still lives in Cleveland. He visits her often and treats her well. When one talks with people who’ve done business with him, the following portrait emerges.

“Brilliant … ambitious … driven … a good listener and observer … he soaks things up and synthesizes information well … always two or three steps ahead of everyone else.”

“Persuasive … patient … calculating … manipulative … extremely well-guarded.”

“Sophisticated … charismatic … gracious and charming when he wants to be … good at complimenting people in the little time he spends with them and making them feel good about themselves.”

Haymon is health conscious, eats a lot of chicken and vegetables, and drinks cranberry juice mixed with club soda. “He isn’t a let’s-go-out-for-dinner-together kind of guy,” says someone who has done business with him for years.

He likes classic old movies and good contemporary ones.

In 2002, he established a non-profit corporation called The Black College Scholarship Fund.

Federal election records list Haymon as having contributed money to several Democratic candidates.

He sold the bulk of his concert promotion business to SFX Entertainment in 1999. Then he cast an eye toward boxing.

Haymon’s business plan for Premier Boxing Champions is as tightly guarded as a nation’s nuclear codes. What’s known is that he now conducts his boxing business through a web of corporate entities with different assets, liabilities and functions. These entities include Haymon Boxing LLC, Haymon Sports LLC, Haymon Holdings LLC and Alan Haymon Development Inc.

He hates the unexpected, doesn’t like to delegate authority and micromanages every detail. He gets what he wants and does things the way he wants.

He has a talent for making people he does business with feel that they’re close to him at a given point in time. But except for a core group – Sylvia Browne, Brad Owens, Sam Watson and Mike Ring – they aren’t.

Browne has been with Haymon since he was in business school in the late-1970s. She’s smart, loyal and does much of his administrative work. “Al trusts Sylvia more than he trusts any other person on earth outside of his mother,” one business associate says.

Owens is Browne’s husband and handles myriad logistical chores for Haymon.

Watson interacts with Haymon’s fighters on a regular basis and does what he can as Al’s representative to keep them happy.

Ring, an attorney, functions as Haymon’s de facto chief of staff and interfaces with providers of venture capital, televison networks and other business allies.

When Haymon has a target in the crosshairs of his mind, he’s incredibly focused. He pushes relationships to the brink when negotiating and has a way of leaving people afraid that if they don’t do what he wants, they’re out. But he knows how to close a deal.

Brian Kweder ran ESPN’s boxing program as senior director of programming and acquisitions from late-2013 through January 2016. He’s now a part-time consultant for Haymon.

“Boxing has its share of swindlers, liars and thiefs, “Kweder says. “Al’s word might be hard to get out of him. But once he gives it, he lives up to it. He always kept his word with me.”

There’s a marked contrast between Haymon’s enormous influence in boxing and his studied ghostlike presence. It would be wrong to say that he stays in the background. In most instances, he’s not even in the picture.

Haymon has an aversion to being interviewed by the media and operates largely out of public view. Like a master puppeteer, he pulls strings but seldom allows himself to be seen. He never wanted to be a public figure. Decades ago, he told Ebony Men, “I’m not trying to be a star. I’m trying to be a businessman.”

Tim Struby noted in a recent profile for Playboy that Haymon “shuns publicity and attention like a vampire avoids sunlight.” Very few photographs of him are available. On those rare occasions when someone gets close enough to ask for a selfie, Haymon’s standard response is, “It’s nice to meet you but I don’t take pictures.”

I’m not trying to be a star. I’m trying to be a businessman. – Al Haymon

As for the fights themselves, Haymon rarely watches from ringside, preferring to view the action from a private box or in an office inside the arena on a TV monitor.

Leon Margules, who promotes fights for Haymon, acknowledges, “Sometimes I see Al onsite when I promote one of his shows; sometimes I don’t. I know he’s there.”

“Al values his privacy,” Margules adds. “He doesn’t even like it when people tell nice stories about him.”

Haymon’s aversion to publicity feeds into a collateral issue. He often seems scornful of and even hostile toward the media, particularly the boxing media.

Haymon has an absolute right to not give interviews. But he has gone beyond that. For example, very few members of the boxing media were invited to the January 14, 2015, press conference at NBC that launched Premier Boxing Champions.

Dan Rafael, perhaps the most widely read boxing journalist in the world, was among the uninvited. “I know Al doesn’t like me,” Rafael says. “And that’s fine. There are people I don’t like either. But I do my job as best I can and expect that basic professional courtesy will be extended to me. And I don’t get that from Al.”

Greg Bishop, now with Sports Illustrated, was on staff at The New York Times when he began researching a story on Haymon in 2011. “I tried to introduce myself to him twice,” Bishop recalls. “Each time, he said, ‘Hey, nice to see you’ and turned away to talk to someone else.”

Dozens of people whom Bishop called either declined comment or failed to return his telephone calls. An attorney for Haymon went so far as to send a cease-and-desist letter to the Times while Bishop was researching his article.

But it’s not just the media that finds Haymon elusive. He often pulls people in and pushes them away as serves his purposes.

Jim Thomas is best known in boxing circles as the attorney who guided Evander Holyfield through the most profitable years of Holyfield’s ring career.

“I had one dealing with Al,” Thomas recalls. “I called him. He answered his cell phone. I said, ‘Hi, this is Jim Thomas. I don’t know if you know who I am.” And before I could get another word out, Al said, ‘How could anyone in boxing not know who Jim Thomas is?’ He was very gracious. I told him what I was interested in. Al said, ‘Let me look at that and get back to you.’ And that was it. I never heard from him again. Al never answered his phone when I called again and none of my calls were ever returned.”

Greg Cohen was Austin Trout’s promoter when Trout brought Haymon in as an advisor.

“At the beginning, it was good,” Cohen says. “Al opened a lot of doors for us at the premium cable networks. Speaking from personal experience, he made me feel as though I was on his team. We only met in person once. That was at the W hotel in Times Square before Austin fought Miguel Cotto at Madison Square Garden (on December 1, 2012). But we spoke on the phone regularly. Al is accessible when he wants to be. And then it got ugly. The moment Al didn’t need me anymore, he cut me off.”

“When Al wants you to, you can talk with him,” says Gary Shaw, who, in the past, promoted some of Haymon’s fighters. “But you can’t reach Al when he doesn’t want to be reached and that’s extremely frustrating when you’re doing business together. You can’t even email Al directly. You email Sylvia Browne, who presumably gives the message to Al. But Al can always say he never got it. He makes you feel like a million dollars until he doesn’t.”

Haymon’s unavailablilty is an instrument of control. He seems to prefer control to equal partnerships.

“Even when I was the promoter of record,” Greg Cohen says, “there were times when I felt like a spectator.”

“Al is a control freak,” says another promoter who has worked extensively with Haymon. “He hates the unexpected, doesn’t like to delegate authority and micromanages every detail. He gets what he wants and does things the way he wants. More than a few times – and I’m paraphrasing now – Al has said to me, ‘Look, that’s the way it has to be.'”

Given the industries that Haymon is in (television and boxing), there’s remarkably little transparency in the way he conducts business. A source with knowledge of the relationship between Haymon and NBC says that NBC executives asked to see the PBC business plan and he declined to show it to them. One NBC executive complained, “He won’t give us simple information that two people transacting business together would normally exchange with one another.”

Promoters who have worked with Haymon – and in some instances still work with him – voice similar sentiments:

- “Al doesn’t tell you what he doesn’t want you to know. And if he doesn’t want you to know something, he’s pretty good at keeping you from finding out.”

- “In the end, it’s Al who puts the pieces together. And the way he sets things up, we don’t even know what the pieces are.”

- “Sometimes the only person who knows what Al is doing is Al. And he leaves surprisingly few fingerprints for a man of his influence and power.”

- “If Al’s plane went down tomorrow, it would be a mess beyond belief.”

Also, there’s an interesting contradiction between Haymon’s low-profile persona and another aspect of his personality.

“For a guy who obsesses about flying under the radar, Al has a huge ego,” one business associate notes. “It’s not about what other people think of him. Al couldn’t care less what the rest of the world thinks except for the handful of people he respects. It’s about what he thinks of himself.”

And a final thought to contemplate until Part II of “What we know about Al Haymon” is posted tomorrow.

Bela Szilagyi was a concert pianist who loved boxing. He and his wife amassed a video archive of fights that were televised between 1979 and 2015. To supplement their income, they sold copies of the videos to TV networks, promoters, managers and others who needed to study a particular fighter or fight.

Sylvia Browne and Brad Owens often ordered videos from the Szilagyis. Many of these videos were of prospective opponents for Haymon’s fighters. But they also ordered a highlight reel of knockouts followed by victorious fighters proclaiming “I want to thank Al Haymon.”

Go to Part II

Hauser is a consultant with HBO Sports.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at [email protected]. His most recent book – A Hurting Sport – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for Career Excellence in Boxing Journalism.