The Ring celebrates the 100th anniversary of Joe Louis’ birth

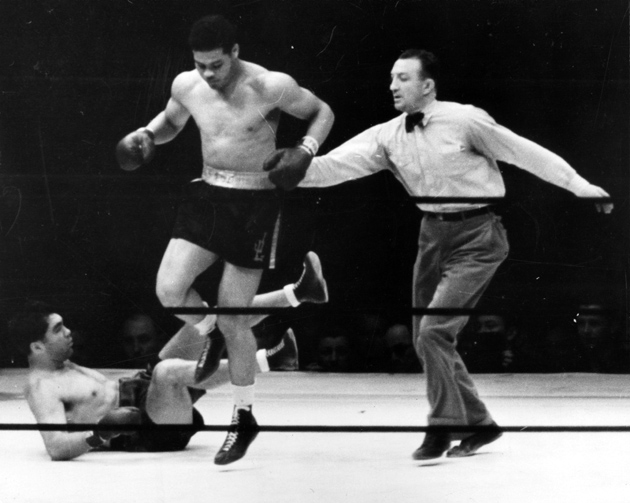

Joe Louis steps over Max Schmeling after knocking him down during their legendary rematch on June 22, 1938 at Yankee Stadium in Bronx, NY. Louis won by first-round KO. Photo / The Ring Magazine-Getty Images

One hundred years ago today Joe Louis, the owner of boxing's greatest championship reign and the athletic catalyst for racial healing in America during the post-slavery era, was born. His life was one of supreme achievement, personal tumult and enormous influence and by the time he died in April 1981 he was arguably his sport's most beloved figure, not just because of his feats inside the ropes but also because of who he was and what he meant to so many.

Joseph Louis Barrow was born May 13, 1914 in LaFayette, Alabama, the seventh of eight children of Munroe and Lillie Barrow. Living in the heart of cotton country Munroe and Lillie, both the offspring of former slaves, made their living alternating between sharecropping and rental farming. The ravages of mental illness caused Munroe to be institutionalized from 1916 until his death in 1938. Lillie's uncle Peter helped with the work duties as they continually moved from harvest site to harvest site. Lillie eventually married Pat Brooks, a widower with nine of his own children, and settled in Camp Hill, Alabama.

Although slavery in the U.S. had been eradicated decades earlier, the racist sentiments that fueled it continued to rage. On their way home from visiting a sick friend late one night, the family was pulled over by a group of Klansmen who was about to pull them out of the car.

“Someone in the crowd recognized my stepfather,” Louis' sister Vunies Barrow High recalled in “Joe Louis: 50 Years an American Hero” by Joseph Louis Barrow Jr. and Barbara Munder. “He said, 'that's Pat Brooks. He's a good n*****.' They didn't bother my parents. My stepfather, however, made up his mind that night he was leaving Alabama.”

Brooks traveled by train to Detroit, where he first secured work as a street sweeper for the city before sending for Lillie, who brought five of his children and four of hers, including Joe. The boys built a boxing ring in the attic of a nearby barn and, unbeknownst to his parents, they boxed other neighborhood children. The positive boxing memories forged in that barn prompted Joe and his friends to visit the Brewster Recreational Center, where Joe began to take boxing lessons. At the time Louis, at the behest of his mother, was taking violin lessons and gave him 50 cents a week to pay for them. But Louis instead used the money to pay for a locker at the rec center. Though irked at first, Lillie was won over by her son's drive to succeed.

“Very well,” she said. “If you're going to be a fighter, be the best you can.”

History would show that Joe's best was far better than most. His named shortened to Joe Louis because there wasn't enough space for his full name on the tournament application, Louis honed his skills under trainer Atler Ellis and a scientific young boxer named Holman Williams. Although he lost his first amateur fight against future 1932 U.S. Olympian Johnny Miler, who floored Louis seven times in two rounds, Louis ended his simon pure career with an outstanding 50-4 (43) record. While working out at the Brewster gym, Louis caught the eye of businessman John Roxborough, who, along with nightclub owner Julian Black, formed Louis' management team when the fighter turned pro in 1934.

After moving Louis' training headquarters to Chicago, Roxborough and Black hired Jack Blackburn as his trainer. Between 1900-1923, the lightweight Blackburn more than held his own against the best fighters of his era – or any era – in Joe Gans, Sam Langford, Harry Greb and Philadelphia Jack O'Brien. His ring smarts enabled him to compete against men far bigger than himself, including heavyweights, and his street smarts allowed him to navigate prison life (where he was jailed for murder) as well as the rough-and-tumble boxing landscape as a trainer. He guided the likes of Sammy Mandell, George Godfrey, Bud Taylor and Sailor Friedman (who challenged welterweight champion Mickey Walker in 1925) but when he was presented with the opportunity to train Louis he initially balked because of the difficulties of making money with an African-American fighter. All it took to change Blackburn's mind was one look at Louis inside a boxing ring.

Not only did Louis have a magnificent physique for his chosen sport – a 76-inch reach on a six-foot-one inch frame, laser-quick reflexes, smoothly formed muscles and concussive power in both fists – he also was willing to spend long hours in the gym perfecting his craft. Blackburn taught Louis to shuffle his feet toward the target in order to establish ideal range for the short, compact punches that followed. The battering-ram jab that tenderized opponents was often changed to a howitzer hook in the blink of an eye and his spring-loaded right crosses tore through opponents with frightening efficiency. His crisp combinations were delivered at a speed that looked even faster when contrasted with Louis' sleepy, deadpan demeanor.

Despite the fact that his pro debut took place 80 years ago, Louis' weaponry would still be considered state-of-the-art in today's game in terms of technique and delivery. Like Sam Snead's golf swing, Ted Williams' batting stroke and John McEnroe's volleys, Louis' form was the picture of perfection. Succeeding generations of teachers would use them as examples of textbook execution and because of that they were able to transcend time.

Louis' professional career began on July 4, 1934 at Bacon's Arena in Chicago in a scheduled six-rounder against Jack Kracken, a 27-7-3 light heavyweight from Norway who had spent the lion's share of his four-year career fighting out of Seattle. Louis cracked Kracken with a trip-hammer hook that produced a nine-count knockdown, then knocked him into the lap of Illinois commission chairman Joe Triner. Though Kracken managed to crawl back into the ring within the mandated 20 seconds, referee Davy Miller waved off the fight. For less than two minutes of ring time, Louis earned $59.

Louis was moved quickly. He fought his first eight-rounder in only his third outing and was moved to 10-rounders by fight six. Every one of Louis' 69 fights was a main event and his string of knockouts over gradually more demanding competition caused a stir throughout the country. However, to reach the ultimate goal – the heavyweight championship of the world – Louis needed to convince the white establishment that he would not rock the boat as Jack Johnson had a generation earlier.

While a number of blacks challenged for and won championships in lighter weight classes, the most prized possession in sports was sealed off from African-American contenders due to Johnson's in-your-face behavior throughout his seven-year reign. To combat those fears – and to draw a vivid contrast between Johnson and Louis – Roxborough and Black had Louis follow a series of rules while in public:

* Never have your picture taken alone with a white woman.

* Never go into a nightclub alone.

* Have no soft fights.

* Have no fixed fights.

* Never gloat over a fallen opponent.

* Keep a solemn expression in front of the cameras.

* Live and fight clean.

Louis' innate modesty and soft-spoken approach made those rules easy to follow and over time the resistance to Louis' advancement softened. Meanwhile, the successes inside the ring continued unabated.

Louis completed a 12-0 (10) 1934 with an eighth-round TKO over Lee Ramage in their first of their two fights while in 1935 he surged toward the top of the heavyweight division with an 11-0 (9) campaign highlighted by consecutive knockouts over Primo Carnera, King Levinsky, Max Baer and Paulino Uzcudun. Unlike 1934, where all but one fight was staged in Chicago, 1935 saw Louis perform in Detroit, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Dayton and, most importantly, New York City. The Carnera and Baer fights were staged at Yankee Stadium while the Uzcudun bout represented Louis' first appearance at “The Mecca of Boxing,” Madison Square Garden. Long before then, Louis had earned an immortal nickname – “The Brown Bomber.”

The Baer fight, boxing's first million-dollar gate in nearly a decade, was perhaps the best demonstration of the young Louis' exquisite savagery. Before 88,150 spectators, Louis' searing jabs, blazing hooks and pulverizing crosses landed with nearly unerring accuracy while Louis absorbed little save for a thrilling exchange near the end of round one. Louis, who married Marva Trotter earlier in the day, floored Baer twice in round three and a third time in the fourth in which Baer sunk to the canvas as if in slow motion.

[springboard type=”video” id=”929393″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

Many suspected Baer could have fought on but given the severe punishment he had already absorbed – and Louis' potential for inflicting far more – the former champion instead chose self-preservation over foolish pride.

“I would have struggled up once more,” Baer said. “But when I get executed, people are going to have to pay more than $25 a seat to watch it.”

After starting 1936 by blowing out Charley Retzlaff in 85 seconds, Louis appeared on the brink of a heavyweight championship fight against Jim Braddock. To get that chance, however, he first had to beat former champion Max Schmeling, who had put together three straight wins following a 1-3-1 stretch that saw him lose the title to Jack Sharkey, brutalize Mickey Walker, drop back-to-back fights to Baer and Steve Hamas and draw with Uzcudun. Two of the three losses were avenged during the recent winning streak (KO 9 Hamas, W 12 Uzcudun) but by fight night Schmeling still was installed as a prohibitive 10-to-1 underdog. Had the oddsmakers known what Schmeling did, those odds might have been much shorter.

Schmeling was at ringside when Louis disposed of Uzcudun and while most of the public saw another classic one-punch knockout, the German spotted a fatal flaw.

“I see something,” he told reporters. When pressed for more details Schmeling wisely kept the information to himself until round four of the fight, which was held at Yankee Stadium on June 19, 1936. It was only then when the former titleholder solved the riddle – and sprung the trap.

“His mistake in this fight was to drop his left for a split second after he used it,” Schmeling said. “He was open for a right. When he did, I went in. He went down. Joe got up after two or three counts, instead of staying down for the full count.”

Time and again Schmeling landed rights over Louis' low left and it was too late for Louis and Blackburn to enact major changes. Louis literally was knocked senseless by the fourth round knockdown, for he had no memory of what happened afterward. What happened was that Schmeling continued to tattoo the overconfident and undertrained Louis with the right and over time the left side of Louis' jaw became badly swollen. A series of hammering rights in round 12 sent Louis spinning to the canvas, after which he shook his head, rolled over on his stomach and took the 10-count from referee Arthur Donovan. The sensational upset was deemed THE RING's 1936 Fight of the Year and Schmeling received a hero's welcome upon his return to Germany, which was led by Adolf Hitler.

By all rights Schmeling should have received the first crack at Braddock but the combination a well-timed postponement and an unprecedented proposition by Braddock's manager Joe Gould to promoter Mike Jacobs resulted in Louis leapfrogging his conqueror. In the eight months after the Schmeling defeat, Louis re-established his credentials as a top contender with seven straight KOs beginning with a three-round destruction of ex-champ Jack Sharkey. The win streak – and a timely delay of a late-1936 Braddock-Schmeling fight due to an arthritic episode in the champ's vaunted right hand – gave Gould time to craft a historic deal for his fighter.

Knowing his charge would probably lose the title to Louis, who at 23 was nine years younger and light years fresher, Gould convinced Jacobs to take the following deal: $300,000 for the fight and 10 percent of Jacobs' net profits from his heavyweight title promotions for the next decade should Louis win. Just like that, the June 3, 1937 Braddock-Schmeling fight at Madison Square Garden turned into a June 22, 1937 Braddock-Louis fight at Chicago's Comiskey Park.

Madison Square Garden's legal team filed suit but New Jersey federal judge Guy L. Fake ruled against MSG. Still, Schmeling trained for the fight and participated in a weigh-in staged by the New York State Athletic Commission but when June 3 rolled around the German was stood up like a jilted prom date.

Louis, the first of his race to fight for the heavyweight crown in 22 years and armed with the tacit approval of American whites, was installed a solid 5-to-2 favorite. Louis was only the third heavyweight title challenger ever to be chosen over the champion (Jeffries over Johnson and Baer over Carnera were the others). But for a moment in round one “The Cinderella Man” appeared as if he was about to slip on the glass slipper for a second time when a short crackling right put Louis on his backside. The challenger arose, then administered a severe beating that slashed Braddock's eye, mouth and ear. A final right to the chin ended matters in round eight and 10 seconds later a new era in boxing was born.

Over the next 57 months Louis successfully defended his heavyweight title an incredible 21 times, smashing Tommy Burns' divisional record of 11. The frequency of his defenses and the ease with which he ultimately disposed of his opponents led many to declare that Louis feasted on a “Bum of the Month Club.” In truth, many of Louis' challengers were solid contenders – Tommy Farr, Nathan Mann, Tony Galento, Bob Pastor, Arturo Godoy, Abe Simon, Buddy Baer, Lou Nova and light heavyweight champions John Henry Lewis and Billy Conn among them – and several of them actually put Louis on the floor (Galento, Godoy and Baer).

Louis long had said that he could not feel like the real champion until he avenged his only defeat against Schmeling. Exactly one year after winning the title from Braddock, Louis-Schmeling II – arguably the most politically-charged match in the sport's history — was staged at Yankee Stadium.

It was here that Louis first used sport to bridge America's cavernous racial divide. With Hitler on the march in Europe and using Schmeling's victory over Louis as proof of “Aryan supremacy,” anti-Nazi sentiment ran high in the States. Louis had long grown accustomed to the pressures of representing his race but here the burdens were broader and deeper. Now he was shouldering the hopes of an entire nation.

A few weeks before the match Louis visited the White House and U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose tenure lasted even longer than Louis' would, told him, “Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Germany.”

Those muscles certainly beat Schmeling on fight night. Before an electric crowd of 70,043 and a worldwide radio audience that numbered more than 100 million, Louis fought as if possessed by an avenging apparition. Louis crowded the challenger at every opportunity while hammering him with punishing combinations. Schmeling, fighting out of a leaning-back crouch, barely threw a punch, much less landed one of consequence.

[springboard type=”video” id=”929377″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

After pushing Schmeling to the ropes, Louis unloaded a series of bombs, one of which was a right that fractured three vertebrae in Schmeling's back, and another that scored a but-for-the-ropes knockdown that drew a brief count from referee Donovan. A crushing right dropped Schmeling for a two-count seconds later and a right to the side of the head caused the challenger to touch both gloves to the canvas. An explosive right to the jaw scored the third official knockdown and caused Schmeling's handlers to run into the ring, ending the fight just 124 seconds after it began. Those listening to the radio broadcast in Germany never heard the end of the fight, for the signal was cut the moment after Schmeling screamed in pain from Louis' punch to the back.

Although the U.S. wouldn't officially enter World War II for another three years, Louis' effort struck a mighty blow for American pride while also being a powerfully uniting force. Louis was regarded as a hero for all Americans regardless of skin color and that image was burnished after he joined the U.S. Army in 1942.

But before he did that, he continued to turn away challengers at an impressive rate. The Schmeling KO was the first of three consecutive first-round knockouts for Louis and his dominance over the boxing world was such that other outstanding fighters were overshadowed. In order to break through the noise Henry Armstrong sought to become the first man ever to hold three undisputed championships simultaneously, a feat he achieved in 1937 and 1938 by beating Pete Sarron for the featherweight title, Barney Ross for the welterweight championship and Lou Ambers for the lightweight belt. Later, the sportswriters of the day bestowed a special label to pay proper tribute to Sugar Ray Robinson's wondrous skills – “pound for pound.”

Though Louis was many times an omnipotent force and continued to win, he did experience occasional stumbles. As previously mentioned Galento (KO 4) and Buddy Baer (DQ 7) scored knockdowns before being dismissed and Godoy, who also decked Louis, managed to push the champion to a split decision in the first of their two fights.

The sternest challenge, however, came from light heavyweight champion Conn, whose movie-star looks and superlative boxing skills flummoxed the slow-footed champion and produced a lead on two of the three scorecards through 12 rounds (7-4-1, 7-5, 6-6 under the rounds system). Commenting on Conn's speed before the bout Louis said, “He can run but he can’t hide,” but now Conn was just nine minutes away from running away with Louis' championship.

[springboard type=”video” id=”929395″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

The seeds of Conn's destruction were sown the moment the challenger's hook rocked Louis with 33 seconds left in the 12th. No longer content to win a decision, Conn ignored the pleadings of his corner and sought the knockout in round 13. The chest-to-chest exchanges with Louis opened Conn up for a ripping right uppercut that clearly stunned the challenger. At that point “The Pittsburgh Kid's” fighting instincts took over, which temporarily held Louis off but in the long run worsened his situation. A wicked right as Conn came in wobbled the challenger, a sinking right-left to the ribs weakened him further, a right uppercut lifted his chin toward the ceiling and a final right to the ear felled him as if in slow motion. The time of the KO: 2:58 of the 13th round.

After dispatching Nova in six rounds, Louis enlisted in the U.S. Army on Jan. 10, 1942, the night after he annihilated Buddy Baer in 176 seconds during their rematch. He donated his entire purse for that fight as well as his rematch win over Abe Simon in March to military charities. Just before the Simon bout Louis spoke at a Navy Relief Society dinner and it was at this event he spoke these famous words:

“I have only done what any red-blood American would do. We gonna do our part and we will win because we're on God's side.”

Billy Rowe, a Louis friend as well as a journalist, was initially horrified by what he thought was a massive linguistic error.

“You dummy!” he exclaimed as written in Barrow Jr.'s book. “You made a big mistake. The phrase is 'we're going to win because God is on our side.'”

“Well, I guess I blew it,” Louis replied.

The next morning Rowe stopped by the hotel to pick up Louis for breakfast.

“When I knocked, he opened the door and threw the newspapers in my face,” he said. “'Who's the dummy now?' he said. His phrase 'we'll win because we're on God's side' became one of the slogans of the war.”

Louis' heartfelt sentiment caused his already high popularity to soar and the whole of his military service, which was spent entirely in the entertainment division, cemented his standing as a role model. Louis traveled more than 70,000 miles in staging nearly 100 boxing exhibitions for an estimated 5 million servicemen, visited countless hospitals and used his position as heavyweight champion to quietly break the chains of racial inequality.

He forwarded his fellow soldiers' complaints about racist treatment to the commanders in Washington, D.C., who then issued orders to the generals at various bases to rectify the problems – which they did. He insisted on integrated crowds at his exhibitions and stood his ground when a military police officer ordered him and Robinson to the rear of an Alabama Army camp bus depot. He wasn't the outspoken revolutionary Muhammad Ali would be a generation later, but his quiet-but-firm approach worked wonders nevertheless.

The conclusion of the war ended Louis' military stint but any possibility of resuming his pre-war life had vanished. Blackburn died of a heart attack in 1942 while Roxborough was imprisoned on gambling charges. His first wife Marva divorced him in March 1945 and his irresponsibility in money matters left him deeply in debt with the IRS as well as with his promoter Jacobs. Finally, his once lithe body was encrusted in rust and extra weight.

With the original team gone, Louis hired numbers man Marshall Miles as manager and Mannie Seamon (an assistant trainer under Blackburn) as chief second. Together they would try to resuscitate the old magic.

The long-awaited rematch with Conn took place five years and one day after the original and Louis won only because the effects of time had been even more unkind to Conn than they had been to the Bomber. Robbed of his speed and sharpness, the 182-pound Conn meekly fell in eight rounds after taking a pinpoint right uppercut-left hook combination to the chin. The good news was that his career-high $625,000 purse paid off many of Louis' past debts to his inner circle. The bad news was that the $100,000 Louis had remaining still wasn't enough to satisfy the $562,500 tax bill on his freshly earned income because it was taxed at a prohibitive 90 percent rate. Therefore, Louis' personal debt clock kept clicking away and the late-payment penalties continued to spiral exponentially upward. One happy development: Louis and Marva remarried one month after the rematch.

Still, Louis was in a terrible bind. He couldn't afford to retire due to his tax woes and with every passing day his once magnificent skills were eroding. He still had enough in the tank to win but the chinks in his armor were there for all to see — and exploit.

Tami Mauriello hurt Louis seriously in the opening moments of their September 1946 encounter before Louis roared back and flattened “The Bronx Barkeep” in 129 seconds. The entire $100,000 purse was supposed to be earmarked for the IRS, which was to receive the money the following January. But because the bout's promoter allowed Louis to dip into the fund, only $500 remained for the tax man when it came time to pay. And so it went. Louis embarked on a world tour to generate more money but all it did was keep the treadmill running.

Less than three months after the Mauriello fight, Jersey Joe Walcott – a veteran journeyman who was so lightly regarded that the New York State Athletic Commission unsuccessfully tried to classify the title fight as an exhibition – nearly snatched the crown from the venerable champion's head.

[springboard type=”video” id=”929399″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

Walcott's tricky shuffles and slick boxing troubled Louis but knockdowns in rounds one and four made an upset a real possibility. When the final bell sounded many were convinced that the 10-to-1 underdog had done the impossible and referee Ruby Goldstein agreed as he had the challenger a 7-6-2 winner in rounds. But he was overruled by judges Frank Forbes (8-6-1) and Marty Monroe (9-6), who deemed Louis the winner, and still champion.

A disgusted Louis nearly left the ring before the decision was announced. Not wanting to end his career on such a sour note – the Bomber was booed out of the ring – Louis fought Walcott again. Despite being dropped in round three and losing on two of the three scorecards, Louis summoned one more dose of greatness by stopping the challenger in the 11th. On March 1, 1949 Louis called a press conference to announce his retirement, ending what remains the longest championship reign in terms of time and title defenses boxing has ever known.

Upon surrendering the championship, Louis was paid $350,000 by the International Boxing Club, which also agreed to pay him a $20,000 annual salary. Walcott and Charles fought for the vacant title, with Charles winning a 15-round decision. Around that time, Marva, finally fed up with Louis' womanizing, divorced him a second time – and this time it was for good.

With the U.S. government hounding him at every turn, the 36-year-old Louis had no alternative but to return to the ring. Worse yet, his first fight back was a title fight against Charles, who by then had notched three successful defenses – all by knockout. Though Louis fought hard and enjoyed some bright moments, they were spaced too far apart and Charles won a lopsided 15-round decision. One judge gave Charles 13 rounds, a second 12 and a third jurist, probably overwhelmed by sentiment, granted Louis five rounds.

Now relegated to non-title fights – and the smaller purses that came with them – Louis returned to the ring just 64 days later and won a 10-round decision over Cesar Brion. In 1951 he fought seven times in eight months and won them all, including three by knockout. Yet with all the penalties from previous balances unsatisfied, Louis' tax bill skyrocketed north of $500,000. In desperate need of funds, Louis agreed to fight a rising undefeated slugger from Brockton, Massachusetts for a $132,000 purse – Rocky Marciano.

“The Brockton Blockbuster” was 37-0 (32) entering the October 1951 bout and at age 28 was near the peak of his powers. Had Louis won, a potential third fight with Walcott was in the offing but at 37 he was old and worn out. As was the case in the Charles fight, Louis showed flashes of the old skills but the New Englander was too strong and hit too hard. A tightly-delivered hook – much like the ones Louis used to flatten opponents back in the day – floored the Bomber for an eight count in round eight. After Louis arose, Marciano trapped the legend along the ropes and wobbled him with a wicked left uppercut. Another left uppercut caused Louis to drop his hands and Marciano, almost as if he was contemplating what he was about to do, took a split second before delivering the final right hand that knocked Louis through the two lower strands of rope and onto the ring apron. It was a profoundly sad but entirely necessary end to a magnificent career.

Though his time in the boxing ring was now over, Louis was forced to continue fighting his most formidable opponent: The IRS. By the mid-1950s his bill had ballooned to more than $1 million and without boxing he was pushed to pursue other avenues that were beyond his natural talents. He appeared on TV shows (one of which had him awkwardly perform a song-and-dance routine), opened a restaurant, bought a horse farm and hawked everything from hair grease, cigarettes, liquor and a soda named Joe Louis Punch. He kept his hand in the boxing game by refereeing and providing guest ringside commentary. The saddest enterprise, however, was professional wrestling. He engaged in a few matches before health issues forced his retirement, but stayed on as a wrestling referee until 1972.

The ferocity of the IRS' pursuit of Louis was a clear signal that the U.S. government held no regard for his past patriotic acts. A particularly low blow: The agency seized the trust funds he set up for his children. Louis' third wife, lawyer Martha Jefferson, brokered a deal with the IRS that would forgive the $1.3 million debt and tax Louis only on future earnings.

Still, Louis' life spiraled downward. He began smoking and drinking heavily and his substance abuse eventually graduated to cocaine. His mental health also deteriorated as severe bouts of paranoia prompted son Joe Jr. to institutionalize him in May 1970. Louis was released six months later and thanks to Caesars Palace executive Ash Resnick, an old Army buddy, Louis was given a job as a greeter.

His final years were marked by multiple health issues. He underwent heart surgery in 1977 and a stroke left him in a wheelchair for the remainder of his life. His last public appearance placed him at ringside for the Larry Holmes-Trevor Berbick heavyweight title fight, which was nationally televised on HBO. Just hours later, Louis died at age 66 of cardiac arrest at Desert Springs Hospital near Las Vegas.

Although Louis was a military veteran, he did not qualify for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. President Ronald Reagan, recognizing Louis' unique contributions to the nation, waived those requirements and cleared the way for the Brown Bomber to be laid to rest with full military honors. Former foe – and longtime friend – Max Schmeling was among the pallbearers.

Joe Louis' accomplishments as a boxer have earned him a rightful place at the sport's pinnacle. According to Boxrec.com, Louis' record was 66-3 (52) and in 27 heavyweight championship fights he was 26-1 (22). He was named THE RING's Fighter of the Year four times – second only to Muhammad Ali's five – and was involved in THE RING's Fight of the Year five times – four times as a winner (Max Baer in 1935, Tommy Farr in 1937, Bob Pastor II in 1939 and Billy Conn I in 1941) and once as a loser (Max Schmeling I). In 2003, the magazine's editors gave Louis the number one spot in their list of boxing's 100 greatest punchers of all time.

Louis re-ignited a sport that was reeling in the depths of The Great Depression and wallowing in the cesspool of systemic corruption. His thunderbolt fists and awe-inspiring efficiency affirmed Louis as a worthy successor to the lineage that began with John L. Sullivan and continued with a pair of Jacks in Johnson and Dempsey. He was victorious in the most politically-fraught fight ever presented and in the process he avenged the lone defeat of his career to that point with a level of dominance that was beyond question.

If one chooses to include Wladimir Klitschko's earlier WBO title reign to his current IBF tenure, “Dr. Steelhammer” is in range of surpassing Louis' record totals of 25 title defenses (Klitschko has 21) and time possessing at least one major heavyweight title belt (10 years 7 months as of May 2014 to Louis' 11 years 255 days). While he may set new standards in terms of raw numbers, he still has much work to do if he wishes to set new benchmarks for consecutive defenses (16) and longest continuous reign (8 years 2 months). If Klitschko fails, Louis' records will likely stand forever.

But as great a fighter as Louis was, his impact as a human being was even more powerful than his crippling crosses. His ring accomplishments first lifted the spirits of his race, then stoked the pride of a country. His dignified manner convinced a skeptical majority that it indeed was ready for a second black heavyweight champion, and his subsequent actions justified the decision to proceed. Once he ascended the throne his sheer majesty helped prepare the path for other sporting trailblazers, the first of which was baseball's Jackie Robinson.

He was one of the few living figures ever to have a sports stadium named for him, as Detroit's Joe Louis Arena – the home of the NHL's Detroit Red Wings and the site of 10 title fights between 1980 and 1999 – was opened in 1979. He was the first boxer ever honored with a postage stamp in the U.S. and countless streets, artistic pursuits and landmarks bear his name or were inspired by him. The Canadian Football League's Winnepeg Blue Bombers' nickname was spawned by local sportswriter Vince Leah's use of Louis' moniker in 1936, when the fighter was still on the rise. In August 1982, Louis was posthumously given the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest award Congress bestows to U.S. citizens, and he was among the 20 fighters inducted as charter members of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

As the world celebrates the 100th anniversary of Louis' birth, one quote attributed to him provides a hint as to why his name occupies such a hallowed place – “You need a lot of different types of people to make the world better.” True leaders throughout the ages have assumed numerous forms and applied a wide variety of styles but in terms of results, few have surpassed Joe Louis' combination of athletic excellence and social transformation. If the mark of a man is his ability to leave this world a far better place than he entered it, then Louis is not only a man of his time, but a man for all time.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 12 writing awards, including nine in the last four years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.

Additional sources: "Joe Louis: 50 Years an American Hero" by Joseph Louis Barrow Jr. and Barbara Munder, "Brown Bomber: The Pilgrimage of Joe Louis" by Barney Nagler, The 1979 Ring Record Book and Boxing Encyclopedia, HBO Sports' "Joe Louis: America's Hero Betrayed" and "The Great Book of Boxing" by Harry Mullan.