(Photo by Justin Setterfield/Getty Images)

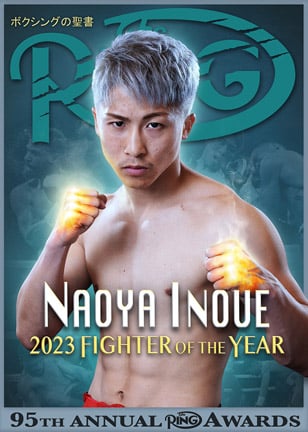

SAUDI ARABIA HAS QUICKLY BECOME ONE OF THE WORLD’S LEADING FIGHT DESTINATIONS BY OFFERING IRRESISTIBLE SUMS OF MONEY TO BOXERS AND PROMOTERS, BUT THE MIGRATION TO THE MIDDLE EAST COMES WITH MULTIPLE CONCERNS

Devin Haney would have barely been out of his post-fight shower at the Chase Center in San Francisco when his promoter, Eddie Hearn, started to speak about the possibility of him fighting in Saudi Arabia next.

In beating Regis Prograis on December 9, Haney had not only just produced the finest performance of his career – one that suggested that at 25 he is at his peak – he had, for the first time, fought and won as the 17,000-strong crowd favorite at a near sold-out arena, and he’d done so in a city far from recognized as one of his profession’s traditional homes.

The fact that, as a resident of Nevada, he was heavily booed in Las Vegas throughout his victory over Vasily Lomachenko in May – in a boxing context, Vegas remains the center of the universe – would have contributed to the sense of satisfaction felt by him and his team. And yet the sights of Haney – a consummate professional along with his father, trainer and manager, Bill Haney, as well as Matchroom’s Hearn – were instead fixed east.

Before he rejoined Matchroom, Haney had come close to an agreement with Skills Challenge Entertainment, the ambitious organization owned by Prince Khalid bin Abdulaziz responsible for staging in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, the rematch in 2022 between Anthony Joshua and Oleksandr Usyk. Perhaps above all else, in contrast to the deliberately cagey-and-diplomatic approach Haney and his father committed to at the conclusion of his promotional agreement with Top Rank following the Lomachenko fight – a tactic that indirectly invited offers without jeopardizing his position of strength as a sought-after world champion and free agent – both he and his promoter were making it known what would ideally come next.

There is hardly a fighter alive whose priority is not to maximize their income. Increasingly – and given that they risk their lives every time they fight, why should it be otherwise? – glory, legacy and tradition are a distant second best. Those who own venues in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia don’t care about fighters any more than any of the world’s other leading fight destinations (and it might yet transpire that they care even less). At least in the case of the world’s leading fighters, however, they pay them even more.

“Saudi Arabia is becoming a real focal point for global sport. It’s not something I expect to slow down.”

– Eddie Hearn

Officials from the country with the Persian Gulf’s biggest economy have made no attempts to hide that the investments made to import the world’s leading sports and respective athletes largely owes to a desire to reduce their reliance on sales of crude oil. A country in which gambling is illegal is ultimately gambling billions of dollars at a time when preserving the planet – partly by vastly reducing, or perhaps even eventually entirely banning, the use of fossil fuels – is, however belatedly, threatening to become a priority for the leaders of the world.

It is hoped by those in Saudi Arabia – not unlike in neighboring Qatar, the host of the 2022 Fifa World Cup – that by hosting some of the highest-profile sporting events on the calendar, they will eventually attract income from tourism capable of compensating for that which could be lost as the world potentially becomes more green. Dubai – a city-state in the United Arab Emirates, which also shares a border with Saudi Arabia – is, in 2024, one of the world’s leading tourist destinations, and largely on account of the significant investments made towards its infrastructure to increase its appeal.

Soccer icon Cristiano Ronaldo and Turki Al-Sheikh, chair of the General Entertainment Authority in Saudi Arabia, watch from ringside at the Day of Reckoning on December 23, 2023, in Riyadh. (Photo by Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

At best, Saudi Arabia appears driven by a projection of soft power. At worst, it appears to be aggressively attempting to “sportswash,” as its critics and campaigners describe it, its appalling human rights record – accusations previously aimed at Qatar and also the UAE and Bahrain, hosts of Formula 1 grands prix.

Riyadh – which will host the endlessly appealing undisputed heavyweight title fight between Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk on February 17, having also hosted Fury-Francis Ngannou in October – is at the center of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s economic and social reforms that have involved the easing of religious restrictions on public life. One high-profile move involved, in 2018 – the same year in Jeddah that Callum Smith stopped George Groves in the final of the super middleweight edition of the World Boxing Super Series – women being granted the right to drive, but over five years later they are far from having the same freedom as men.

Days after Groves-Smith, the Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi walked into his country’s consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, to collect the document he needed to marry his Turkish fiancee, but it was there that he was ambushed by a 15-strong Saudi hit squad, who suffocated him and dismembered his body with a bone saw before leaving on two charter planes owned by the same Saudi sovereign wealth fund that is paying for the divisive LIV Golf tour. Bin Salman, according to U.S. intelligence officials, approved Khashoggi’s assassination. In 2022 – the same year Jeddah hosted Usyk-Anthony Joshua II – the Saudi state passed the Personal Status Law that preserves the expectation that women will obey their husbands.

Bin Salman also, as recently as December – little over two weeks before Joshua, Deontay Wilder, Jai Opetaia and Dmitry Bivol fought on the same bill – met with Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia overseeing his country’s murderous invasion of Ukraine. At a time when the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia and the European Union are among those imposing sanctions on Russia as a consequence of that invasion, the Saudi Press Agency quoted the crown prince as saying of that meeting: “We share many interests and many files that we are working on together for the benefit of Russia, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Middle East and the world as well.”

Anthony Joshua at the Diriyah Arena in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. (Photo by Nick Potts/PA Images via Getty Images)

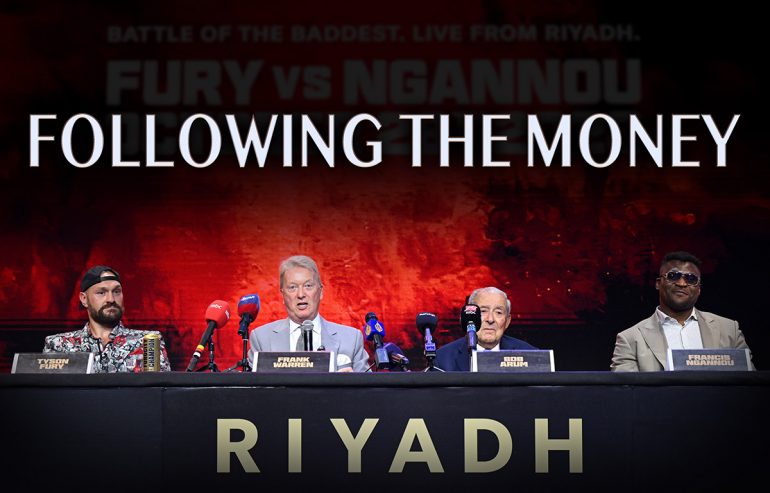

Money rarely spoke more loudly than in November when Hearn and Frank Warren, for so long the bitterest of enemies, met and cooperated for the first time to help publicize the December 23 promotion led by Joshua-Otto Wallin and Wilder-Joseph Parker (in December in Saudi Arabia, they even publicly shook hands). Rarely have two individuals’ interests been so in conflict – the fiercely proud promoters typically favor different broadcasters, rival fighters and similar territory – and largely because of the money, status and influence they almost always stand to lose or gain. Yet as seamlessly as Joshua stopped Wallin, the political landscape and rival agendas that have so often been portrayed as insurmountable were overcome because the money being offered to fund the appropriately named “Day of Reckoning” was far too vast to resist.

It was on October 28, when Fury struggled in victory over Ngannou, and in the immediate aftermath of those struggles when the decision was made for the previous date of December 23 for Fury-Usyk to be postponed. Eight weeks later, those then considered the world’s third and fourth finest heavyweights, its finest cruiserweight and perhaps its finest fighter at 175 pounds were ready to fight. The progress made was, by the standards of those in boxing in the modern era, unprecedented – it involved satisfying numerous typically irrepressible egos and overcoming long-term hostility and tension, but it proved relatively seamless because of the overinflated sums of money being paid.

Neither Groves-Smith nor Amir Khan-Billy Dib, both of which were staged in 2019, were fights capable of attracting the widespread attention those in Saudi Arabia were hoping for, but that December on a Matchroom bill Joshua fought, for the second time, Andy Ruiz in Diriyah for the IBF, WBA and WBO heavyweight titles. The world heavyweight title – once the richest prize in sport – was being bought once again.

Promoter Eddie Hearn beside Abdullah Ahmed Eid Al-Harbi, president of the Saudi Arabia Boxing Federation. (Photo by Francois Nel/Getty Images)

“We wasted so many years talking about big fights in the Middle East (Khan once believed he had agreed to a date with Manny Pacquiao in Dubai in 2017) – none of them ever materialized,” Hearn told The Ring.

“That was just an approach from someone who knew Prince Khalid – who was in charge of Skills Challenge – who reached out to me and said, ‘I want to do Joshua-Ruiz II.’ I said, ‘We’re moving quickly; we don’t want to waste time, but thanks for your interest. I’ve been through this so many times with the Middle East and it never happens.’ ‘How much is it?’ ‘This much.’ ‘Send me the contracts and we’ll do it.’

“It comes back with a million changes. I went back to him and said, ‘Please don’t waste my time – goodbye.’ [They] sign the contract. A huge deposit in escrow’s supposed to be paid in 48 hours – seven days later, it hadn’t come through. I phoned him up – and I always joke about this with Prince Khalid – and said, ‘Please don’t waste my time ever again. Goodbye.’ Then I got a phone call from the bank to say that the money had dropped, and I had to phone back and apologize to Prince Khalid. That was the start of it all.

“The problem with fights out there is you are forgoing a lot of the natural revenue that you’d receive [at more traditional venues], and they have to cover all that and pay a premium. The premium’s not as much now, because boxing’s in Saudi Arabia, but at the time it’s, ‘If you want us to take this from Vegas or [Wales’] Millennium Stadium and go all the way to the Middle East with the fighters, it’s gonna have to be a lot of money.’

“I think the plan for them is to bring that premium down, because it’s unsustainable to making a proper business.

“Every fighter does want to fight in Vegas and Madison Square Garden, but Saudi’s now become an important part of the calendar – [and] not just because of the money.

“After Joshua-Ruiz II, the plan was for us to do a lot more shows, but COVID came, so we had three years out until we returned with Joshua-Usyk [II]. They’re sports fans. A lot of the people behind these events – his Excellency Turki Al-Sheikh (who chairs his country’s General Entertainment Authority) is a massive fight fan. He knows everything – watches everything. They’re big football fans. ‘Let’s bring the best to Saudi Arabia.’ It comes from a sports background, and of course they want to bring attention to their country, and by bringing the biggest events from chosen sports, they’re doing that.

“Saudi Arabia is becoming a real focal point for global sport. It’s not something I expect to slow down.

“I expect them to do three-to-six megafights a year. They understand the market now. They’re the ones that can make the fights happen, because all of the little bits and pieces that people argue about… it’s like me and Warren working together. The money’s so big for the fighters, we just go, ‘Let’s not mess this up.’ I don’t think Fury necessarily wanted to fight Usyk, but once he asked for a number and it got delivered, it’s in. It’s more money than you can make for that fight anywhere else. It’s very difficult to say no.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is flanked by Evander Holyfield and FIFA President Gianni Infantino at the Oleksandr Usyk-Anthony Joshua rematch on August 20, 2022. (Photo by Giuseppe Cacace/ AFP)

Warren, Hearn and Bob Arum – who co-promoted Fury-Ngannou – and Fury, Usyk and Joshua are far from the first to willingly accept money from potentially damaging sources. The alleged narcoterrorist Daniel Kinahan continues to cast a shadow over boxing; the Thrilla in Manila and the Rumble in the Jungle, perhaps the two most storied heavyweight title fights of all time, were bought by the cruelest of dictators, respectively Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines and Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire. Of the sports continuing to work with Saudi Arabia, however, boxing is the one that first readily accepted their money.

“They want the elite,” said Hearn, “and it’s always good to grow boxing in the territory, but they’re not going to be looking at British champions and saying, ‘Yeah, let’s bring him.’ [Ring Magazine cruiserweight champion] Jai Opetaia’s a good example – they watched him fight and said, ‘Let’s have him in Saudi Arabia.’”

In referencing Opetaia, Hearn had just been asked about Saudi Arabia’s approach of building from the top down instead of what appears for the long-term, but their approach regardless isn’t as one-dimensional as from a distance it might appear. In the weeks before Fury-Ngannou, contributors to The Ring were among those approached by the General Entertainment Authority regarding what was described as an “Editorial team position for a boxing venture in Saudi Arabia” – and it is little secret among those in the boxing media that there were then individuals they might describe as “colleagues” attempting to discourage those at Fury-Ngannou from reporting on the wider picture of the reality of the country at the expense of the event for which Saudi Arabia had paid.

As ever, the web is as wide as it is potentially complicated, and successful at recruiting those whose priorities are perhaps even more short-term. In the same week in 2022 that Joshua was as unconvincing as so many of the world’s leading golfers and footballers when asked about Saudi Arabia’s sportswashing efforts, a woman by the name of Salma al-Shehab was sentenced to 34 years in prison there because, on social media, she followed and reposted dissidents.

Given Fury’s historic association with Kinahan, the U.S. government’s sanctions against the Kinahan crime cartel and the fact that Fury was banned from entering America, it seems unlikely that Fury-Usyk – a fight first announced with little warning – would otherwise be taking place. Usyk-Joshua II also owed much to the power brokers of Saudi Arabia, and along with the vast finances, Usyk – a vocal, articulate, modest and unusually human ambassador for Ukraine at so significant a time in his country’s history – is in so many ways the counterintuitive common denominator in both.

Those involved in boxing were among the most natural and obvious of buyable assets within the greater picture of Saudi Arabia’s ambitions. Fury and Usyk – not unlike Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier in the Philippines and Ali and George Foreman in Zaire – will share a reported purse of $154 million. But for all of the cost to Saudi Arabia, what will eventually be the cost to boxing and the wider world?

Declan Warrington is on X (Twitter):