Before Day Turns to Dusk

IKE IBEABUCHI PONDERED A COMEBACK DURING A BRIEF PERIOD BETWEEN INCARCERATIONS, BUT THE FORMER HEAVYWEIGHT CONTENDER’S MENTAL STATE AT THE TIME WAS CAUSE FOR ALARM

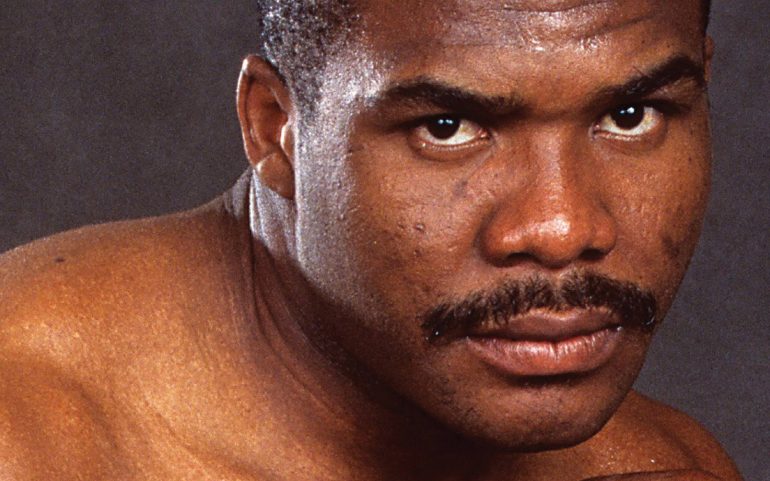

I was an Ike Ibeabuchi fan the moment I watched his battle with David Tua on a pirated video I ordered from a classified ad in the back of Boxing Monthly magazine. The Nigerian powerhouse seemed to have everything needed to win the heavyweight title – except mental stability.

A few years after he was jailed for battery and sexual assault, I decided to go digging in search of the real Ike Ibeabuchi, aiming to discover what built and then broke the man who had the boxing world at his feet after he destroyed Chris Byrd in 1999.

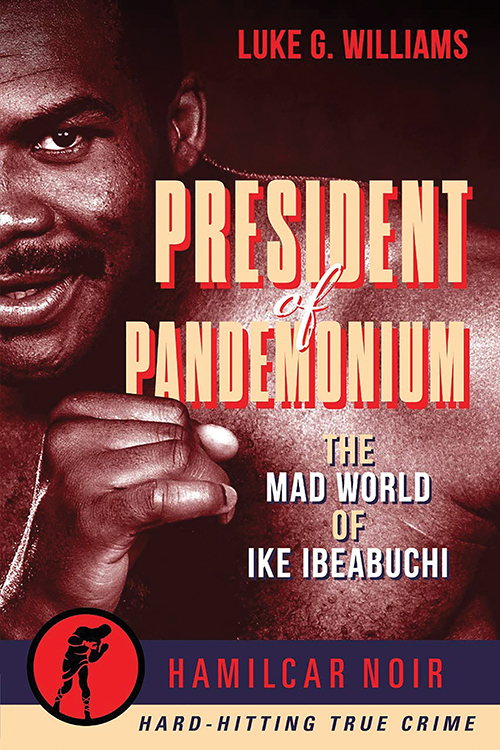

While researching the book that would become President of Pandemonium: The Mad World of Ike Ibeabuchi, I spoke to thirty people who knew Ike – including those who fought him, managed him, advised him and reported on him. I discovered that some thought he was insane, while others thought he was more sinned against than sinner.

This excerpt from my book – coming this October from Hamilcar – tells the story of the day I spoke to Ike and includes the views of former HBO executive Lou DiBella, matchmaker Eric Bottjer and trainer Bill Benton.

When I spoke to Ike Ibeabuchi on a February afternoon in 2016, he could scarcely believe he was free.

Maybe he knew it couldn’t last. Or maybe he had become too hardened by his tour of federal institutions. Being removed from a place inhabited by killers and rapists and placed in suburbia must be disorientating. Out of the harsh and dehumanizing experience of an ICE detention center, or the sterile menace of a maximum-security prison, Ibeabuchi could now enjoy the unbroken sight of winter sunshine and the soft breeze blowing in from the desert.

As we spoke, the forty-three-year-old former heavyweight contender from Nigeria sat in a spare room of an aunt’s house in Gilbert, Arizona. Because “aunt” is an appellation applied loosely in Nigeria to both blood relatives and others, it wasn’t clear what Ike’s connection to his “aunt” was. Regardless, since his release from custody, he had sat here for hours fixated on the world heavyweight championship he still believed was his destiny, despite the fact it was nearly seventeen years since he had thrown a punch in a prizefight. Since 1999, Ibeabuchi’s professional record had stood still, perfect and unbroken.

Twenty fights, twenty wins, fifteen knockouts.

When he wasn’t at his aunt’s, Ibeabuchi was training hard at a 24-hour branch of LA Fitness, anonymously going about the grim business of working his forty-something body into shape among insomniac gym freaks and overweight office workers. As he fielded messages on his cell phone from promotional and media bloodsuckers and posed for grainy photographs in boxing gear – snarl still on his bearded face – it must have been easy to convince himself that he still had a shot at the heavyweight title.

Ike Ibeabuchi (right) in his classic 1997 showdown with fierce power-puncher David Tua.

Images of post-prison Ibeabuchi soon began to spread across the Internet, exciting those old enough to remember his thrilling war with David Tua and his shocking destruction of Chris Byrd. Social media platforms were soon ablaze with debates about whether Ibeabuchi could or should make a comeback.

Ike was happy to stoke the anticipation.

“I have unfinished business in boxing,” Ibeabuchi told me, his quiet voice never wavering. “It’s more a case of why shouldn’t I come back, rather than why I should. My strength is that I have not been defeated. So let’s fight and let’s see if any heavyweights can prove or disprove my ability. Most people might think I should have retired by now, but I haven’t been a world champion. To me that is an insult, so I have to redeem myself. I want to be a world champion before day turns to dusk.”

Amid this optimistic defiance, however, one question got a somewhat different reaction.

“How does it feel to be free, Mr. Ibeabuchi?” I asked.

“I don’t know if I am free yet,” he said. “I won’t feel free until I step into the ring.”

***

Most people who worked in boxing in the 1990s have an Ike Ibeabuchi story. And each one is more unbelievable than the next. One night, Ibeabuchi was having lunch in New York with his promoter, Cedric Kushner, and HBO executive Lou DiBella. What happened next was both bizarre and unsettling. “I can deal with anybody and I don’t get scared easily,” DiBella recalled. “I’ve seen everything in thirty years of boxing, but I never saw anyone plunge a steak knife into a table in front of me before Ike Ibeabuchi did.”

DiBella continued: “We hadn’t even got into serious conversation. It was just chitchat, pleasantries. I asked him: ‘Where do you live, Ike?’ He looked at me and said: ‘Why do you want to know where I live? Why are people concerned with where I live? Is someone looking for me? Why do you want to know where I live?’ And after that little expression of dismay, he plunged the fucking steak knife into the table.”

Recalling the incident a year or two later, Kushner admitted that his fighter’s behavior “wasn’t the type of conduct I expected to romance the guy from HBO.”

More than two decades later, Ibeabuchi remains an enigma. Many who knew him insist he was mentally ill to the extent that he was a danger to himself and to others. Eric Bottjer, former matchmaker for Kushner, insisted: “I’ve been around boxing a long time, long enough to realize that it’s not a normal profession and a lot of boxers are not normal human beings, but Ike is the only fighter I’ve ever met who I would say was literally insane.”

The legal wreckage Ibeabuchi caused from 1997 onward – including allegations, charges, or convictions connected to sexual assault, kidnapping and attempted murder – make for grim reading, especially when you consider the human cost of his deeds, which include a teenage boy left permanently damaged and unable to walk properly as well as several prostitutes who lost their minds.

The legal wreckage Ibeabuchi caused from 1997 onward – including allegations, charges, or convictions connected to sexual assault, kidnapping and attempted murder – make for grim reading, especially when you consider the human cost of his deeds, which include a teenage boy left permanently damaged and unable to walk properly as well as several prostitutes who lost their minds.

“I recall having a conversation with Cedric where I said I thought Ike was a dangerous human being who was capable of killing somebody,” Bottjer recalled. “Not that he had made any threats to me or anybody on our staff, but, being around him, that was the impression I formed. Thankfully he never did [murder anyone], but having said that, he certainly did harm to that boy in Texas and the woman in Las Vegas.”

There’s another narrative, however, advanced by Ike himself and his late mother, Patricia – a tale of conspiracy in which mysterious men stole embryos to breed a future world heavyweight champion. It’s the type of story you might find in the pages of a pulp novel, one in which Ibeabuchi is the victim, a man immersed in the corrupt world of boxing who encounters exploitation at every turn. There are also those who firmly deny Ibeabuchi is the crazed monster he has often been portrayed as. “Ike was a good man with a good heart,” insists Bill Benton, the trainer and matchmaker who was arguably closer to him than anyone else in the boxing business. “Forget boxing, he did beautiful and good things that people never talk about.”

Putting aside for now Ibeabuchi’s mental health, we must first look at what can’t be questioned, the facts of his boxing career – facts that have helped him reach mythical status in heavyweight boxing history. His record – 20-0 with 15 knockouts – isn’t necessarily impressive. In modern boxing, any mediocre heavyweight who is guided carefully can build such a record. What created Ibeabuchi’s status as one of boxing’s great “what if” stories were two defining fights – the ones he fought against David Tua in 1997 and Chris Byrd in 1999.

The strength of these two performances – as well as images of Ibeabuchi exchanging bombs with Tua and knocking out Byrd – conjure what might have happened had he battled the likes of Lennox Lewis, Evander Holyfield and Mike Tyson.

Boxing fans love to debate what could have been, particularly when it comes to wasted or unfulfilled talent. Ike, however, doesn’t give a fuck: “The Holyfield fight did not happen, nor Lewis or Tyson,” he declared. “Commenting on them would be crying over spilled milk.”